The Never ‑Ending Story: Czech Governments, Corruption And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

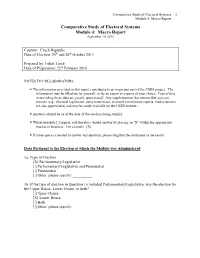

Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 4: Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012 Country: Czech Republic Date of Election: 25th and 26th October 2013 Prepared by: Lukáš Linek Date of Preparation: 23rd February 2016 NOTES TO COLLABORATORS: . The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] . If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [X] Parliamentary/Legislative [ ] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [X] Lower House [ ] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __________ Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 4: Macro Report 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election, regardless of whether the election was presidential? Party of Citizens Rights-Zemannites (SPO-Z). -

The Czech President Miloš Zeman's Populist Perception Of

Journal of Nationalism, Memory & Language Politics Volume 12 Issue 2 DOI 10.2478/jnmlp-2018-0008 “This is a Controlled Invasion”: The Czech President Miloš Zeman’s Populist Perception of Islam and Immigration as Security Threats Vladimír Naxera and Petr Krčál University of West Bohemia in Pilsen Abstract This paper is a contribution to the academic debate on populism and Islamophobia in contemporary Europe. Its goal is to analyze Czech President Miloš Zeman’s strategy in using the term “security” in his first term of office. Methodologically speaking, the text is established as a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis (CAQDAS) of a data set created from all of Zeman’s speeches, interviews, statements, and so on, which were processed using MAXQDA11+. This paper shows that the dominant treatment of the phenomenon of security expressed by the President is primarily linked to the creation of the vision of Islam and immigration as the absolute largest threat to contemporary Europe. Another important finding lies in the fact that Zeman instrumentally utilizes rhetoric such as “not Russia, but Islam”, which stems from Zeman’s relationship to Putin’s authoritarian regime. Zeman’s conceptualization of Islam and migration follows the typical principles of contemporary right-wing populism in Europe. Keywords populism; Miloš Zeman; security; Islam; Islamophobia; immigration; threat “It is said that several million people are prepared to migrate to Europe. Because they are primarily Muslims, whose culture is incompatible with European culture, I do not believe in their ability to assimilate” (Miloš Zeman).1 Introduction The issue of populism is presently one of the crucial political science topics on the levels of both political theory and empirical research. -

Lustration Laws in Action: the Motives and Evaluation of Lustration Policy in the Czech Republic and Poland ( 1989-200 1 ) Roman David

Lustration Laws in Action: The Motives and Evaluation of Lustration Policy in the Czech Republic and Poland ( 1989-200 1 ) Roman David Lustration laws, which discharge the influence of old power structures upon entering democracies, are considered the most controversial measure of transitional justice. This article suggests that initial examinations of lustrations have often overlooked the tremendous challenges faced by new democracies. It identifies the motives behind the approval of two distinctive lustration laws in the Czech Republic and Poland, examines their capacity to meet their objectives, and determines the factors that influence their perfor- mance. The comparison of the Czech semi-renibutive model with the Polish semi-reconciliatory model suggests the relative success of the fonner within a few years following its approval. It concludes that a certain lustration model might be significant for democratic consolidation in other transitional coun- tries. The Czech word lustrace and the Polish lustrucju have enlivened the forgotten English term lustration,’ which is derived from the Latin term lus- Roman David is a postdoctoral fellow at the law school of the University of the Witwa- tersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa ([email protected]; [email protected]). The original version of the paper was presented at “Law in Action,” the joint annual meeting of the Law and Society Association and the Research Committee on the Sociology of Law, Budapest, 4-7 July 2001. The author thanks the University for providing support in writing this paper; the Research Support Scheme, Prague (grant no. 1636/245/1998), for financing the fieldwork; Jeny Oniszczuk from the Polish Constitutional Tribunal for relevant legal mate- rials; and Christopher Roederer for his comments on the original version of the paper. -

Thatcherism Czech Style

TITLE : Thatcherism, Czech Style : Organized Labor and the Transition to Capitalism in the Czech Republic AUTHOR: Peter Rutland Wesleyan University THE NATIONAL COUNCI L FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEA N RESEARC H 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 INFORMATIONPROJECT :* CONTRACTOR : Brown University PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Linda J . Coo k COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 807-24 DATE : April 30, 199 3 COPYRIGHT INFORMATION Individual researchers retain the copyright on work products derived from research funded b y Council Contract. The Council and the U.S. Government have the right to duplicate written reports and other materials submitted under Council Contract and to distribute such copies within th e Council and U.S. Government for their own use, and to draw upon such reports and materials for their own studies; but the Council and U.S. Government do not have the right to distribute, o r make such reports and materials available outside the Council or U.S. Government without th e written consent of the authors, except as may be required under the provisions of the Freedom o f Information Act 5 U.S.C. 552, or other applicable law . The work leading to this report was supported by contract funds provided by the National Council fo r Soviet and East European Research . The analysis and interpretations contained in the report are those of th e author. CONTENT S Executive Summary i Roots i i The Political Consolidation of the Market Reformers i i The Economic Reform Program iii The Role of Labor Unions in the Transition t o -

Download Article

5 Comment & Analysis CE JISS 2008 Czech Presidential Elections: A Commentary Petr Just Again after fi ve years, the attention of the Czech public and politicians was focused on the Presidential elections, one of the most important milestones of 2008 in terms of Czech political developments. The outcome of the last elections in 2003 was a little surprising as the candidate of the Civic Democratic Party (ODS), Václav Klaus, represented the opposition party without the necessary majority in both houses of Parliament. Instead, the ruling coalition of the Czech Social Democratic Party (ČSSD), the Christian-Democratic Union – Czecho- slovak Peoples Party (KDU-ČSL), and the Union of Freedom – Democratic Union (US-DEU), accompanied by some independent and small party Senators was able – just mathematically – to elect its own candidate. However, a split in the major coalition party ČSSD, and support given to Klaus by the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSČM), brought the Honorary Chairman of the ODS, Václav Klaus, to the Presidential offi ce. In February 2007, on the day of the forth anniversary of his fi rst elec- tion, Klaus announced that he would seek reelection in 2008. His party, the ODS, later formally approved his nomination and fi led his candidacy later in 2007. Klaus succeeded in his reelection attempt, but the way to defending the Presidency was long and complicated. In 2003 members of both houses of Parliament, who – according to the Constitution of the Czech Republic – elect the President at the Joint Session, had to meet three times before they elected the President, and each attempt took three rounds. -

How Teachers Cope with Social and Educational Transformation

How Teachers Cope with Social and Educational Transformation Struggling with Multicultural Education in the Czech Classroom Dana Moree EMAN 2008 How Teachers Cope with Social and Educational Transformation Struggling with Multicultural Education in the Czech Classroom Hoe docenten omgaan met sociale en educatieve veranderingen met een samenvatting in het Nederlands Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit voor Humanistiek te Utrecht op gezag van de Rector, prof. dr. Hans Alma ingevolge het besluit van het College van Hoogleraren in het openbaar te verdedigen op 24 november 2008 des voormiddags te 10.30 uur door Dana Moree Geboren op 20 November 1974 te Praag PROMOTORES: Prof.dr. Wiel Veugelers Universiteit voor Humanistiek Prof.dr. Jan Sokol Charles University Praag Co-promotor: Dr. Cees Klaassen Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen BEOORDELINGSCOMMISSIE: Prof. dr. Chris Gaine University of Chichester Prof.dr. Ivor Goodson University of Bristol Prof. dr. Douwe van Houten Universiteit voor Humanistiek Dr. Yvonne Leeman Universiteit van Amsterdam Dr. Petra Zhřívalová Charles University Praag This thesis was supported by the projects: The Anthropology of Communication and Human Adaptation (MSM 0021620843) and Czechkid – Multiculturalism in the Eyes of Children. for Peter, Frank and Sebastian EMAN, Husova 656, 256 01 Benešov http://eman.evangnet.cz Dana Moree HOW TEACHERS COPE WITH SOCIAL AND EDUCATIONAL TRANSFORMATION Struggling with Multicultural Education in the Czech Classroom First edition, Benešov 2008 © Dana Moree 2008 Typhography: Petr Kadlec Coverlayout: Hana Kolbe ISBN 978-80-86211-62-6 7 Contents Acknowledgements . 9 Introduction . 10 Chapter 1 – Transformation of the cultural composition of the Czech Republic . 15 Introduction . -

Public Opinion and Democracy In

PUBLIC OPINION AND DEMOCRACY IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE (1992-2004) by Zofia Maka A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science and International Relations Summer 2014 © 2014 Zofia Maka All Rights Reserved UMI Number: 3642337 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3642337 Published by ProQuest LLC (2014). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 PUBLIC OPINION AND DEMOCRACY IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE (1992-2004) by Zofia Maka Approved: __________________________________________________________ Gretchen Bauer, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Political Science and International Relations Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ James G. Richards, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: __________________________________________________________ Julio Carrion, Ph.D. -

The Václav Havel Library Annual Report 2017 2 Lidé Knihovny Václava Havla

The Václav Havel Library Annual Report 2017 2 Lidé Knihovny Václava Havla Published in 2018 by the charity the Václav Havel Library registered at the Municipal Court in Prague, file O 338 dated 26 July 2004 statutory representative: Michael Žantovský address: Ostrovní 13, 110 00 Prague 1 Identification no. 27169413 / Tax identification no. CZ 27169413 Bank accounts: 7077 7077 / 0300 CZK; IBAN: CZ61 0300 0000 0000 7077 7077 7755 7755 / 0300 EUR; IBAN: CZ40 0300 0000 0000 7755 7755 7747 7747 / 0300 USD; IBAN: CZ66 0300 0000 0000 7747 7747 SWIFT CODE: CEKO CZPP Tel.: (+420) 222 220 112 Email: [email protected] The Václav Havel Library is registered according to the libraries law under registration no. 6343/2007 at the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic www.vaclavhavel-library.org www.facebook.com/KnihovnaVaclavaHavla www.facebook.com/VaclavHavelLibrary www.youtube.com/knihovnaVaclavahavla www.twitter.com/KnihovnaVH www.twitter.com/HavelLibraries www.instagram.com/knihovnaVaclavahavla Lidé Knihovny Václava Havla 3 It only makes sense as a living or vital organism that occupies a place that cannot be overlooked in overall public and political life. […] The Library must in some way be original as such, in itself, in its everyday nature, as a permanently existing phenomenon or place. Václav Havel A Few Sentences on the Václav Havel Library Hrádeček 4 Contents Contents on the preparation of film documents THE VÁCLAV HAVEL LIBRARY and retrospectives PEOPLE OF THE VÁCLAV HAVEL LIBRARY PUBLISHING ACTIVITIES Founders Best-selling -

The Vision of Europe in the New Member States

Studies & Research N°50 The Vision of Europe in the New Member States Notre Europe asked different personalities of the New Member States to give their vision of Europe in 2020 Contributions of Carmel Attard (Malta), Jiři Dienstbier (Czech Republic), Jaan Kaplinski (Estonia), Ioannis Kasoulides (Cyprus), Manja Klemenčič (Slovenia), Lena Kolarska-Bobinska (Poland), Lore Listra (Estonia), Petr Pithart (Czech Republic), Pauls Raudseps (Latvia), Gintaras Steponavicius (Lithuania), Elzbieta Skotnicka-Illasiewcz (Poland), Miklós Szabo (Hungary). Summary by Gaëtane Ricard-Nihoul, Paul Damm and Morgan Larhant Authors of the summary Gaëtane Ricard-Nihoul Graduate from Liege University in political science and public administration, Gaëtane Ricard- Nihoul was awarded a Mphil and a Dphil in European politics and society by Oxford University. Her research focused on policy formation in the European Union, and more particularly on education policy. From 1999 to 2002, she was in charge of the team for "European and international affairs", in the cabinet of the Belgian Vice-Prime Minister Isabelle Durant, also Minister for Mobility and Transport. She acted, among other things, as a coordinator during the Belgian presidency of the EU Council. As an adviser for insitutional matters, she represented the Vice-Prime Minister in the Belgian delegation at the WTO ministerial conference in Seattle and also in the Inter- Governemental Conference, taking part in the Biarritz, Nice and Laeken European Councils. She was also a member of the Belgian government working group on the Laeken Declaration. Gaëtane Ricard-Nihoul then joined the European Commission Directorate-General for Education and Culture, in the Audiovisual Policy unit. Employed in the Sector for external relations, she was in charge of the accession negociations with the 13 applicant countries for audiovisual matters as well as the relations with countries from the Western Balkans and South Mediterranea. -

The Rise and Decline of the New Czech Right

Blue Velvet: The Rise and Decline of the New Czech Right Manuscript of article for a special issue of the Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics on the Right in Post-Communist Central and Eastern Europe Abstract This article analyses the origins, development and comparative success centre-right in the Czech Republic. It focuses principally on the the Civic Democratic Party (ODS) of Václav Klaus, but also discusses a number of smaller Christian Democratic, liberal and anti-communist groupings, insofar as they sought to provide right-wing alternatives to Klaus’s party. In comparative terms, the article suggests, the Czech centre-right represents an intermediate case between those of Hungary and Poland. Although Klaus’s ODS has always been a large, stable and well institutionalised party, avoiding the fragmentation and instability of the Polish right, the Czech centre- right has not achieved the degree of ideological and organisational concentration seen in Hungary. After discussing the evolution and success of Czech centre-right parties between 1991 and 2002, the article reviews a number of factors commonly used to explain party (system) formation in the region in relation to the Czech centre- right. These include both structural-historical explanations and ‘political’ factors such as macro-institutional design, strategies of party formation in the immediate post-transition period, ideological construction and charismatic leadership. The article argues that both the early success and subsequent decline of the Czech right were rooted in a single set of circumstances: 1) the early institutionalisation of ODS as dominant party of the mainstream right and 2) the right’s immediate and successful taking up of the mantel of market reform and technocratic modernisation. -

The Russian Connections of Far-Right and Paramilitary Organizations in the Czech Republic

Petra Vejvodová Jakub Janda Veronika Víchová The Russian connections of far-right and paramilitary organizations in the Czech Republic Edited by Edit Zgut and Lóránt Győri April, 2017 A study by Political Capital The Russian connections of far-right and paramilitary organizations in the Czech Republic Commissioned by Political Capital Budapest 2017 Authors: Petra Vejvodová (Masaryk University), Jakub Janda (European Values Think Tank), Veronika Víchová (European Values Think Tank) Editor: Lóránt Győri (Political Capital), Edit Zgut (Political Capital) Publisher: Political Capital Copy editing: Zea Szebeni, Veszna Wessenauer (Political Capital) Proofreading: Patrik Szicherle (Political Capital), Joseph Foss Facebook data scraping and quantitative analysis: Csaba Molnár (Political Capital) This publication and research was supported by the National Endowment for Democracy. 2 Content Content ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Foreword .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Main findings .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Policy -

Political Participation of Women in the Czech Republic Summary of the Country Report

Summary of the POLITICAL Country Report (1993 – 2013) PARTICIPATION OF WOMEN IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC Mgr. Veronika Šprincová Mgr. Marcela Adamusová Fórum 50 %, o.p.s | www.padesatprocent.cz Political Participation of Women in the Czech Republic Summary of the Country Report Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................... 4 1. European Parliament .................................................................................. 5 2. National Politics ......................................................................................... 8 2.1. Lower House of the Czech Parliament ...................................................... 8 2.2. Upper House of the Czech Parliament .................................................... 10 2.3. Women in the Government .................................................................... 11 2.4. Regional and Local Politics...................................................................... 14 2.4.1. Regional Assemblies ......................................................................... 14 2.4.2. Local Assemblies ............................................................................... 16 2.5. Women in Czech Political Parties ........................................................... 18 2 Political Participation of Women in the Czech Republic Summary of the Country Report List of Tables and Figures Chart no. 1: The number of women elected to the European Parliament in 2004 and 2009 for each member state