Men on the Margin: Onscreen Outsiders and American Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thoreau As an Oblique Mirror: Jon Krakauer's Into the Wild

American Studies in Scandinavia, 47:1 (2015), pp. 40-60. Published by the Nordic Association for American Studies (NAAS). Thoreau as an Oblique Mirror: Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild José Sánchez Vera Karlstad University Abstract: In his nonfiction biography of Christopher McCandless, Into the Wild, Jon Krakauer uses a plethora of references to Henry D. Thoreau. In this article I analyze Krakauer’s use of Thoreau’s economic ideas, liberalism, and view of nature and wil- derness. I argue that Krakauer blurs a pragmatic understanding of Thoreau and uses techniques of fiction to create an appealing story and characterize McCandless as a latter-day Thoreauvian transcendentalist. By doing so, Krakauer explains and de- fends the protagonist’s actions from criticism, thereby making him appear as a char- acter whose story is exceptional. Although the characterization of the protagonist as a follower of Thoreauvian ideals by means of a partial interpretation of Thoreau does not provide us with a better understanding of McCandless’s life, Krakauer’s extensive research and the critical self-reflection in the text produces a compelling nonfiction narrative. Moreover, the romantic image of Thoreau advanced by Krakauer reflects the preoccupations and issues that concerned Krakauer, or at least his times. Particu- larly, it reflects Krakauer’s own ideas concerning the negative effects of materialism on both ourselves and the natural world. Key words: Jon Krakauer, Henry David Thoreau, Into the Wild, nonfiction, nature, transcendentalism Into the Wild is Jon Krakauer’s nonfiction biography of Christopher Mc- Candless, a talented college graduate who inexplicably leaves his family, his friends, and all the comforts of civilization in search of ultimate free- dom, a nobler form of life closer to nature and divorced from the extreme materialism of American society. -

The Chris Mccandless Obsession Problem

The Chris McCandless Obsession Problem Diana Saverin, Outside Magazine, December 18, 2013 On the isolated shore of the Savage River, in the backcountry of interior Alaska, there‘s a small memorial to a deceased woman named Claire Ackermann. A pile of rocks sits on a metal plaque with an inscription that reads, in part: ―To stay put is to exist; to travel is to live.‖ Three years ago, Ackermann, 29, and her boyfriend, Etienne Gros, 27, tried to cross the Teklanika River, a couple of miles west from the Savage. They tied themselves to a rope that somebody had run from one bank to the other, to aid such attempts. The Teklanika is powerful in summertime, and about halfway across they lost their footing. The rope dipped into the water, and Ackermann and Gros, still tied on, were pulled under by its weight. Gros grabbed a knife, cut himself loose, and swam to shore. He waded back out to try and rescue Ackermann, but it was too late—she had already drowned. He cut her loose and swam with her body 300 yards downstream, where he dragged her to land on the river‘s far shore. His attempts at CPR were useless. Ackermann, who was from Switzerland, and Gros, a Frenchman, had been hiking the Stampede Trail, a route made famous by Christopher McCandless, who walked it in April 1992. Many people now know about McCandless and how the 24-year-old idealist bailed out of his middle- class suburban life, donated his $24,000 in savings to charity, and embarked on a two-year hitchhiking odyssey that led him to Alaska and the deserted Fairbanks City Transit bus number 142, which still sits, busted and rusting, 20 miles down the Stampede Trail. -

Multi-Platinum Grammy Winner Tobymac Announces ‘Eye on It’ Tour Featuring Special Guests Chris August and Jamie Grace

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: MULTI-PLATINUM GRAMMY WINNER TOBYMAC ANNOUNCES ‘EYE ON IT’ TOUR FEATURING SPECIAL GUESTS CHRIS AUGUST AND JAMIE GRACE 10-City Major-Market Tour Kicks Off October 4th, Supports New Album Release EYE ON IT NASHVILLE, TN – August 28, 2012–Five-time GRAMMY® winner anD multi-platinum selling artist TobyMac is following up the release of his brand new stuDio album, EYE ON IT, with a major-market tour of the same name. HeaDliner TobyMac will be joineD by fellow artists Chris August anD Jamie Grace on the EYE ON IT Tour, slateD to kick off Oct. 4, in Dallas. The tour will hit 10 major markets throughout miD-America during the month of October incluDing Dallas, Houston (Cypress), Minneapolis, Columbus (Grove City), Louisville (KY) anD St. Louis, among others. Two of the tour’s largest markets – Houston anD Minneapolis – have alreaDy sold out. The EYE ON IT Tour comes on the heels of TobyMac’s fifth solo stuDio album release, EYE ON IT, which features his latest No. 1 single, “Me Without You.” On its Aug. 28 release Day, EYE ON IT simultaneously claimeD two of the Top 10 positions on iTunes’ Top Albums, with the Deluxe EDition lanDing at No. 1 anD the album’s regular version at No. 10. To celebrate the album’s release, TobyMac recently made his national television Debut performance of “Me Without You,” SaturDay, Aug. 25, on the hit cable morning show “Fox & FrienDs,” anD followeD that with a special guest appearance MonDay, Aug. 27, on ABC’s “Good Morning America,” performing with fellow Grammy nominee ManDisa. -

Contradictionary Lies: a Play Not About Kurt Cobain Katie

CONTRADICTIONARY LIES: A PLAY NOT ABOUT KURT COBAIN KATIE WALLACE Bachelor of Arts in English/Dramatic Arts Cleveland State University May 2012 Master of Arts in English Cleveland State University May 2015 submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN CREATIVE WRITING at the NORTHEAST OHIO MFA and CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 We hereby approve this thesis For KATIE WALLACE Candidate for the MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN CREATIVE WRITING degree For the department of English, the Northeast Ohio MFA Program And CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY’S College of Graduate Studies by ________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chairperson, Imad Rahman ____________________________________________________ Department and date _________________________________________________________________ Eric Wasserman _____________________________________________________ Department and date ________________________________________________________________ Michael Geither ____________________________________________________ Department and date Student’s date of defense April 19, 2018 CONTRADICTIONARY LIES: A PLAY NOT ABOUT KURT COBAIN KATIE WALLACE ABSTRACT Contradictionary Lies: A Play Not About Kurt Cobain is a one-act play that follows failed rocker Jimbo as he deals with aging, his divorce, and disappointment. As he and his estranged wife Kelly divvy up their belongings and ultimately their memories, Jimbo is visited by his guardian angel, the ghost of dead rock star Kurt Cobain. Part dark comedy, -

5713 Theme Ideas

5713 THEME IDEAS & 1573 Bulldogs, no two are the same & counting 2B part of something > U & more 2 can play that game & then... 2 good 2 b 4 gotten ? 2 good 2 forget ! 2 in one + 2 sides, same story * 2 sides to every story “ 20/20 vision # 21 and counting / 21 and older > 21 and playing with a full deck ... 24/7 1 and 2 make 12 25 old, 25 new 1 in a crowd 25 years and still soaring 1+1=2 decades 25 years of magic 10 minutes makes a difference 2010verland 10 reasons why 2013 a week at a time 10 things I Hart 2013 and ticking 10 things we knew 2013 at a time 10 times better 2013 degrees and rising 10 times more 2013 horsepower 10 times the ________ 2013 memories 12 words 2013 pieces 15 seconds of fame 2013 possibilities 17 reasons to be a Warrior 2013 reasons to howl 18 and counting 2013 ways to be a Leopard 18 and older 2 million minutes 100 plus you 20 million thoughts 100 reasons to celebrate 3D 100 years and counting Third time’s a charm 100 years in the making 3 dimensional 100 years of Bulldogs 3 is a crowd 100 years to get it right 3 of a kind 100% Dodger 3 to 1 100% genuine 3’s company 100% natural 30 years of impossible things 101 and only 360° 140 traditions CXL 4 all it’s worth 150 years of tradition 4 all to see (176) days of La Quinta 4 the last time 176 days and counting 4 way stop 180 days, no two are the same 4ming 180 days to leave your mark 40 years of colorful memories 180° The big 4-0 1,000 strong and growing XL (40) 1 Herff Jones 5713 Theme Ideas 404,830 (seconds from start to A close look A little bit more finish) A closer look A little bit of everything (except 5-star A colorful life girls) 5 ways A Comet’s journey A little bit of Sol V (as in five) A common ground A little give and take 5.4.3.2.1. -

Krist Novoselic

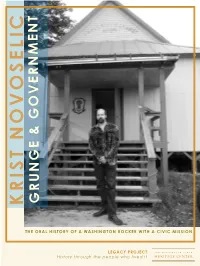

OVERNMENT G & E GRUNG KRIST NOVOSELIC THE ORAL HISTORY OF A WASHINGTON ROCKER WITH A CIVIC MISSION LEGACY PROJECT History through the people who lived it Krist Novoselic Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes October 14, 2008 John Hughes: This is October 14, 2008. I’m John Hughes, Chief Oral Historian for the Washington State Legacy Project, with the Offi ce of the Secretary of State. We’re in Deep River, Wash., at the home of Krist Novoselic, a 1984 graduate of Aberdeen High School; a founding member of the band Nirvana with his good friend Kurt Cobain; politi cal acti vist, chairman of the Wahkiakum County Democrati c Party, author, fi lmmaker, photographer, blogger, part-ti me radio host, While doing reseach at the State Archives in 2005, Novoselic volunteer disc jockey, worthy master of the Grays points to Grays River in Wahkiakum County, where he lives. Courtesy Washington State Archives River Grange, gentleman farmer, private pilot, former commercial painter, ex-fast food worker, proud son of Croati a, and an amateur Volkswagen mechanic. Does that prett y well cover it, Krist? Novoselic: And chairman of FairVote to change our democracy. Hughes: You know if you ever decide to run for politi cal offi ce, your life is prett y much an open book. And half of it’s on YouTube, like when you tried for the Guinness Book of World Records bass toss on stage with Nirvana and it hits you on the head, and then Kurt (Cobain) kicked you in the butt . -

Into the Wild and Transcendentalism

Into the Wild and Transcendentalism C. Cangemi [email protected] AP English Language & Composition Unit Overview This lesson sequence is designed for Advanced Placement English Language & Composition students; however, it can be easily modified for any 11th or 12th grade English class. While students will gain significant knowledge of Transcendental ideas and thorough knowledge of the myriad literary works that inspired Chris McCandless, the protagonist in Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild, a major focus in this lesson sequence is for students to hone comprehension skills through intense and repeated close readings of challenging texts (the types of texts that can be found on the AP exam). There are 10 lessons included here, attached to 10 (out of 18) various chapters in Into the Wild. This particular lesson plan begins after a thorough introduction to Into the Wild and a classroom reading of Chapter 1. Each lesson will run for at least one 48-minute period, but flexibility is important because some of these lessons can go two or even three days depending on the discussion that is generated by the students. The unit will focus on the following threads: ● “Living in Nature” ● “Examining Desperate and Deliberate Lives” ● “Practicing Simplicity” ● “Choosing Life with Principle” ● “Relationships” It’s important for students to pay attention and track these threads because their final assessment requires them to write about one of them. Most of these threads will be introduced with a reading from Henry David Thoreau. However, an introduction to Ralph Waldo Emerson and Transcendentalism will be presented with the third lesson. Essential/Framing Questions 1. -

Music History Lecture Notes Modern Rock 1960 - Today

Music History Lecture Notes Modern Rock 1960 - Today This presentation is intended for the use of current students in Mr. Duckworth’s Music History course as a study aid. Any other use is strictly forbidden. Copyright, Ryan Duckworth 2010 Images used for educational purposes under the TEACH Act (Technology, Education and Copyright Harmonization Act of 2002). All copyrights belong to their respective copyright holders, • Rock’s classic act The Beatles • 1957 John Lennon meets Paul McCartney, asks Paul to join his band - The Quarry Men • George Harrison joins at end of year - Johnny and the Moondogs The Beatles • New drummer Pete Best - The Silver Beetles • Ringo Star joins - The Beatles • June 6, 1962 - audition for producer George Martin • April 10, 1970 - McCartney announces the group has disbanded Beatles, Popularity and Drugs • Crowds would drown of the band at concerts • Dylan turned the Beatles on to marijuana • Lennon “discovers” acid when a friend spikes his drink • Drugs actively shaped their music – alcohol & speed - 1964 – marijuana - 1966 – acid - Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery tour – heroin in last years Beatles and the Recording Process • First studio band – used cutting-edge technology – recordings difficult or impossible to reproduce live • Use of over-dubbing • Gave credibility to rock albums (v. singles) • Incredible musical evolution – “no group changed so much in so short a time” - Campbell Four Phases of the Beatles • Beatlemania - 1962-1964 • Dylan inspired seriousness - 1965-1966 • Psychedelia - 1966-1967 • Return to roots - 1968-1970 Beatlemania • September 1962 – “Love me Do” • 1964 - “Ticket to Ride” • October 1963 – I Want To Hold your Hand • Best example • “Yesterday” written Jan. -

Krist Novoselic, Dave Grohl, and Kurt Cobain

f Krist Novoselic, Dave Grohl, and Kurt Cobain (from top) N irvana By David Fricke The Seattle band led and defined the early-nineties alternative-rock uprising, unleashing a generation s pent-up energy and changing the sound and future of rock. THIS IS WHAT NIRVANA SINGER-GUITARIST KURT Cobain thought of institutional honors in rock & roll: When his band was photographed for the cover of Rolling Stone for the first time, in early 1992, he arrived wearing a white T-shirt on which he’d written, c o r p o r a t e m a g a z i n e s s t i l l s u c k in black marker. The slogan was his twist on one coined by the punk-rock label SST: “Corporate Rock Still Sucks.” The hastily arranged photo session, held by the side of a road during a manic tour of Australia, was later recalled by photogra pher Mark Seliger: “I said to Kurt, T think that’s a great shirt... but let’s shoot a couple with and without it.’ Kurt said, ‘No, I’m not going to take my shirt off.’” Rolling Stone ran his Fuck You un-retouched. ^ Cobain was also mocking his own success. At that moment, Nirvana - Cobain, bassist Krist Novoselic, and drummer Dave Grohl - was rock’s biggest new rock band, propelled out of a long-simmering postpunk scene in Seattle by its incendiary second album, N everm ind, and an improbable Top Ten single, “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Right after New Year’s Day 1992, Nevermind - Nirvana’s first major-label release and a perfect monster of feral-punk challenge and classic-rock magne tism, issued to underground ecstacy just months before - had shoved Michael Jackson’s D angerous out of the Number One spot in B illboard. -

Within “Walden” by Henry David Thoreau and “The Death of An

Transcendentalism: Ethereal Experience or Tragic Naiveté? Within “Walden” by Henry David Thoreau and “The Death of an Innocent by Jon Krakauer, the individual’s search for isolation and a transcendental experience is illustrated with drastically different results. While both Thoreau and McCandless are indeed idealistic, Thoreau walked away from Walden Pond, McCandless did not. Your assignment is to analyze the similarities and differences of their transcendental experiences. Use: Thoreau’s “Walden” on page 205 of your texts. Krakauer’s “The Death of an Innocent” from Outside magazine (see below) Venn Diagram Outside Magazine January 1993 Death of an Innocent How Christopher McCandless lost his way in the wilds By Jon Krakauer James Gallien had driven five miles out of Fairbanks when he spotted the hitchhiker standing in the snow beside the road, thumb raised high, shivering in the gray Alaskan dawn. A rifle protruded from the young man's pack, but he looked friendly enough; a hitchhiker with a Remington semiautomatic isn't the sort of thing that gives motorists pause in the 49th state. Gallien steered his four-by-four onto the shoulder and told him to climb in. The hitchhiker introduced himself as Alex. "Alex?" Gallien responded, fishing for a last name. "Just Alex," the young man replied, pointedly rejecting the bait. He explained that he wanted a ride as far as the edge of Denali National Park, where he intended to walk deep into the bush and "live off the land for a few months." Alex's backpack appeared to weigh only 25 or 30 pounds, which struck Gallien, an accomplished outdoorsman, as an improbably light load for a three-month sojourn in the backcountry, especially so early in the spring. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. February 24, 2020 to Sun. March 1, 2020

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. February 24, 2020 to Sun. March 1, 2020 Monday February 24, 2020 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT The Top Ten Revealed The Very VERY Best of the 70s Guitar Rock Intros - Find out which epic Guitar Intros make our list as rock experts like Lita Ford, Teen Flicks - We’re ranking your favorite teen flicks of the 70s. From slapstick to romance, these Steven Adler (GnR) and Vinnie Paul (Pantera) count us down! movies had the teens of the 70s flocking to theaters. Find out which 70s teen flicks made our list as Barry Williams, Sebastian Bach and Anson Williams give us their opinions! 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT The Day The Rock Star Died 7:30 AM ET / 4:30 AM PT John Denver - Often described as “among the most beloved entertainers of his era,” John Denver TrunkFest with Eddie Trunk recorded and released approximately 300 songs, with total sales of over 33 million records Mountain Jam - In this episode of TrunkFest, Eddie heads to New York for Mountain Jam and worldwide. His lyrics reflected his joy in nature and disdain for city life, his enthusiasm for music, checks out the historic grounds of Woodstock, widely considered the home of festivals as we and his relationship trials. know them. Special guests include George Clinton. 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT The 53rd Annual CMA Awards Rock Legends Country Music’s biggest stars are coming together on one stage at The 53rd Annual CMA Awards Elton John - This documentary follows Elton John’s journey from budding songwriter to his 70s - Country Music’s Biggest Night with host Carrie Underwood and special guest hosts Reba McEn- peak as the one of the most prolific artists of his generation, his flamboyant costumes and tire and Dolly Parton in celebration of legendary women in Country Music! Watch as the Country classic songs and closing with being one of the very few musicians who can still top the charts Music industry reveals winners and honors its finest entertainers. -

Nirvana Bleach Download Free

Nirvana bleach download free Nirvana – Bleach (Album ). Track listing: 1. “Blew” 2. “Floyd the Barber” 3. “About a Girl” 4. “School” 5. “Love Buzz” 3. Band: Nirvana Album: Bleach Year: Label: Sub Pop. Genre: Grunge / Alternative Band From: Washington, USA Audio Bitrate. Download Nirvana - Bleach (Full Album MP3) See More. Money can't buy happiness, but it can buy all the albums of NIRVANA · Nirvana Kurt CobainThe. Bootleg: Bleach Out! Break Out! Tracks: 13 Bootleg Rating Performance Date: 8 July Location: Club. Switch browsers or download Spotify for your desktop. Bleach: Deluxe Edition. By Nirvana. • 25 songs . Listen to Bleach: Deluxe Edition now. Listen to. “Breed” Nirvana - Bleach (FULL ALBUM HQ) - Duration: tdruK, views Download here –. test. ru Nirvana – Nevermind Free Download MP3 ZIP/RAR. Download Nirvana nevermind super deluxe edition . Free download nirvana bleach rar full version. nirvana nevermind album rar, nirvana unplugged. Wszystko o muzyce, gwiazdach i wydarzeniach związanych z nirvana bleach download free. Newsy nirvana bleach download free. Zdjęcia nirvana bleach. Sub Pop are releasing on November 3rd a 20th-Anniversary remastered deluxe edition of Nirvana's Bleach including an unreleased live. Find a Nirvana - Bleach first pressing or reissue. Complete your Nirvana collection. Shop Vinyl and Coupon for free download of HiQ MP3s of entire album. Buy Bleach: Read 81 Digital Music Reviews - Start your day free trial of Unlimited to listen to this album plus tens of millions more songs. on orders over $25—or get FREE Two-Day Shipping with Amazon Prime. Only 11 left in stock (more on the way). Ships from and sold by Gift-wrap.