Volume 17 Symposium Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 COMMONWEALTH of PENNSYLVANIA HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE on JUDICIARY Ouse Bill 1141

1 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON JUDICIARY ouse Bill 1141 * * * * * Stenographic report of hearing held in Majority Caucus Room, Main Capitol Building, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Friday, April 28, 1989 10:00 a.m. THOMAS CALTAGIRONE, CHAIRMAN MEMBERS OF COMMITTEE ON JUDICIARY ry Birmelin Hon. Christopher K. McNally hard Hayden Hon. Nicholas B. Moehlmann id W. Heckler Hon. Robert D. Reber ard A. Kosinski sent: antz. Executive Director lley, Minority Counsel Reported by: Ann-Marie P. Sweeney, Reporter ANN-MARIE P. SWEENEY 536 Orrs Bridge Road Camp Hill, PA 17011 2 INDEX PAGE gner, Southeast Regional Dir., 3 Ivamans vs. Pornography st. Esquire, United States Attorney 57 eters, Esquire, Legal Counsel, 74 al Obscenity Law Center wn, Southeast Coordinator, 78 Ivamans vs. Pornography Viglietta, Director, Justice and 96 Department, Pennsylvania Catholic ence 3 CHAIRMAN CALTAGIRONE: We'll start the ngs. Members will be coming in. We do have some Df the Judiciary Committee present - Jerry , Dob Reber, Chris McNally, and the staff a Director, Dave Krantz. There will be others L be coming in as the proceedings go on today. I'd like to introduce myself. I'm State bative Tom Caltagirone, chairman of the House f Committee. Today's hearing is on House Bill 'd like to welcome everybody that's in attendance ay, and I'd like to call as our first witness jner, who is the Southeast Regional Director of 3ylvanians vs. Pornography. Frank. MR. WAGNER: Mr. Chairman and members of the f Committee, I'm here today to testify on behalf flvanians vs. Pornography. PVP is a congress of nography works located here in the Commonwealth ides some 43 county anti-pornography tions, the Pennsylvania Catholic Conference, ania Council of Churches, Pennsylvamans for Morality, Concerned Women of America, the Eagle nd the Pennsylvania Knights of Columbus. -

Breastfeeding Guide

Breastfeeding Guide Woman’s Hospital has been designated by the Louisiana Maternal and Child Health Coalition to be a certified Guided Infant Feeding Techniques (GIFT) hospital for protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding. The GIFT designation is a certification program for Louisiana birthing facilities based on the best practice model to increase breastfeeding initiation, duration and support. Earning the GIFT certification requires a hospital to demonstrate that it meets the “Ten Steps to a Healthy, Breastfed Baby” and the criteria for educating new parents and hospital staff on the techniques and importance of breastfeeding. Woman’s believes in the importance of breastfeeding and improving Louisiana’s breastfeeding rates. The Gift is a joint effort between the Louisiana Maternal and Child Health Coalition and the Louisiana Perinatal Commission and is supported by the Louisiana Office of Public Health – Maternal and Child Health Program. Exclusive Breastfeeding Recommended The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of a baby’s life. This recommendation is based on scientific evidence that shows benefits for a baby’s survival and proper growth and development. Breast milk provides all the nutrients that a baby needs during the first six months. Contents Congratulations ............................................................................................2 Supporting the New Mother and Her Decision to Breastfeed ................2 -

Sex Issue 2008

TUDENT IFE THE SINDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER OF WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY L IN ST. LOUIS SINCE 1878 SPECIAL ISSUE WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 13, 2008 WWW.STUDLIFE.COM X2 STUDENT LIFE | NEWS Senior News Editor / Sam Guzik / [email protected] WEDNESDAY | FEBRUARY 13, 2008 Student Life When did you lose Ahh. Another year, another Sex Issue survey. While the results vary each year, the main purpose of survey remains constant: to discover students’ expectations, experiences and your virginity? opinions on relationships and sex. 1.67% However, there were some notable changes made this year. 2008 marked the fi rst time 14 and under Student Life conducted the survey online, leading to an unprecedented 1550 undergradu- 10.11% ate responses collected. The survey has a theoretical margin of error of two percent. 15-16 We also sorted some of the data based on gender, relationship status and other factors to see if there were any interesting delineations. However, no generalizations were made 40.50% based on sexual orientation because the number of respondents who chose options other 28.40% Still a virgin than heterosexual was too low to supply suffi cient data for an accurate analysis. 17-18 Data complied by David Brody and Shweta Murthi Graphic design by Joe Rigodanzo and Anna Dinndorf 17.45% 19-20 1.80% 21-22 The average WU student has sex _______ I do 24% Are you a Virgin? less often than 60% Freshmen 55% 65% Sophmores more often 55% Juniors than Art School 21% Seniors 50% as often sexuality as 45% 40% 88% of Art and Architec- ture students identify as 35% heterosexual, the lowest 30% percentage of any school. -

California Hard Core

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title California Hard Core Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0g37b09q Author Duong, Joseph Lam Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California California Hard Core By Joseph Lam Duong A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Waldo E. Martin, Chair Professor Kerwin Lee Klein Professor Linda Williams Spring 2014 Copyright 2014 by Joseph Lam Duong Abstract California Hard Core by Joseph Lam Duong Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Waldo E. Martin, Chair California Hard Core is a narrative history of the pornographic film industry in California from 1967 to 1978, a moment when Americans openly made, displayed, and watched sexually explicit films. Two interrelated questions animate this project: Who moved the pornographic film from the margins of society to the mainstream of American film culture? What do their stories tell us about sex and sexuality in the U.S. in the last third of the twentieth century? The earlier academic literature concentrates on pornographic film and political debates surrounding it rather than industry participants and their contexts. The popular literature, meanwhile, is composed almost entirely of book-length oral histories and autobiographies of filmmakers and models. California Hard Core helps to close the divide between these two literatures by documenting not only an eye-level view of work from behind the camera, on the set, and in the movie theater, but also the ways in which consumers received pornographic films, placing the reader in the viewing position of audience members, police officers, lawyers, judges, and anti-pornography activists. -

BREASTFEEDING Q. Why Should I Breastfeed? A. Breast Mild Provides Perfectly Balanced Nutrition for Your Baby and Is Ideally Su

BREASTFEEDING Q. Why should I breastfeed? A. Breast mild provides perfectly balanced nutrition for your baby and is ideally suited for a baby’s immature digestive system. Your breast milk also provides your baby with important immune resistance to allergens and illnesses. Breastfeeding benefits you also by causing the uterus to contract to the pre-pregnancy size more quickly and be producing the hormone prolactin, which stimulates relaxation. Q. What is my nipples become sore or cracked? A. Correct your baby’s latch on for proper sucking, keep your nipples dry, wear a good fitting nursing bra and nurse more frequently (which is the opposite of what you want to do), and alternate nursing positions. Also, massage your breasts, and avoid using soap on your nipples. Products to soothe and help heal sore, chapped or cracked nipples are available. Q. How do I know if my nursing bra is right? A. A properly fit nursing bra helps support your breasts. A bra cup that is too tight, or that has no give, can constrict the milk ducts causing mastitis and discomfort. Our certified fitters can assist you in finding the right fit for you. Q. How do I know if my flange on my breast pump is fitting correctly or if I need a bigger size. A. Your WHBaby Breast Pump comes with two flange sizes. Using the silicone flange cover it is 24 mm. Without the silicone flange cover it is 27 mm. We also have a 30 mm large pumping kit if needed. Here is a link for how to measure for proper flange fitting. -

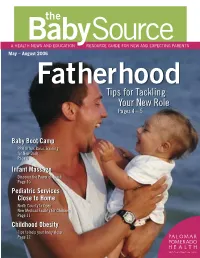

Tips for Tackling Your New Role Pages 4 – 5

A HEALTH NEWS AND EDUCATION RESOURCE GUIDE FOR NEW AND EXPECTING PARENTS May – August 2006 Fatherhood Tips for Tackling Your New Role Pages 4 – 5 Baby Boot Camp PPH Offers Basic Training for New Dads Page 6 Infant Massage Discover the Power of Touch Page 10 Pediatric Services Close to Home North County to Open New Medical Facility for Children Page 11 Childhood Obesity Tips to help your baby sleep Page 12 Class Locations Poway San Marcos Volume 2 – Issue 2 Pomerado Hospital The HealthSource May – August 2006 15615 Pomerado Road 120 Craven Road Poway, CA 92064 Suite 103 Editor-in-Chief 858.613.4000 San Marcos, CA 92069 Janet Gennoe Director of Marketing & The HealthSource Women’s Health Connection Escondido [email protected] Gateway Medical Building Palomar Medical Center 15725 Pomerado Road Content Editors Suite 100 555 East Valley Parkway Poway, CA 92064 Escondido, CA 92025 Mary Coalson 858.613.4894 760.739.3000 Health Education Specialist [email protected] Tammy Chung Assistant to The HealthSource [email protected] Off-site classes are also available for groups, businesses and other organizations Contributors that would like instruction on a particular Gustavo Friederichsen health topic. Call 858.675.5372 for more information. Chief Marketing & Communications Offi cer [email protected] Tami Weigold Marketing Manager [email protected] Numbers to Know Kathy Lunardi, R.N. Community Nurse Educator Keep these important numbers handy for use in the event of an emergency. [email protected] Emergency Crisis Hotlines -

Breastfeeding Secrets Tips and Tricks from a Mom of Three to Survive the first Year of Breastfeeding Baby Table of Contents

Breastfeeding Secrets Tips and tricks from a mom of three to survive the first year of breastfeeding baby Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. About The Author 3. 10 Breastfeeding Tips Every 4. 5 Tips to Naturally Increase New Mom Should Know Your Breast Milk Supply 5. The Secret to Keeping Your 6. 10 Breastfeeding Hacks the Breastfed Baby Full Nursing Mom Needs in Her Life 7. Breastfeeding in Public: Tips 8. How to Survive Breastfeeding to Feel Comfortable at Night (Tips to Stay Awake & Be Prepared) 9. Breastfeeding in the Summer: 10. 9 Must-Try Tips for Getting a How to Survive the Heat with Breastfed Baby to Take a Bottle Baby 11. Breastfeeding Truths: The 12. 10 Powerful Pumping Tips to Pros & Cons Every Mom Should Increase Your Efficiency & Pump Know More Milk Introduction Breastfeeding Secrets: Tips and tricks to survive the first year of breastfeeding baby Breastfeeding is a beautiful, nature part of motherhood. But that doesn't mean it is easy. In fact, most new moms find it extremely overwhelming. That's where Breastfeeding Secrets comes in. How this book can help on your breastfeeding journey The tips and tricks included in this ebook are compiled from some of the most popular posts featured on MommysBundle.com including: How to increase your milk supply How to breastfeed in public without fear Using a breast pump more efficiently to build up a stash How to keep your breastfed baby full Tips for staying awake and breastfeeding at night Getting a breastfed baby to take a bottle ... AND MORE! As a breastfeeding mother of three, I know how overwhelming the journey may seem. -

Police UNDER FIRE It's Your Choice to Call Us BEFORE (Or After) It Fails!

★ ★ ★ SPECIAL REPORT ★ ★ ★ September 21, 2015 • $3.95 www.TheNewAmwww.TheNewAmerican.com POLICE UNDER FIRE It's your choice to call us BEFORE (or after) it fails! Ronald A. Britton, P.E., DABFET “Professional Engineering And Consulting At Its Best” Rohill Operating Company, Ltd. | 3100 North “A” Street, Suite E-200 | Midland, Texas 79705-5367 | 432-686- 0022 First Ten Amendments to the Constitution Amendment I. Congress shall make no law respecting an life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or property be taken for public use, without just compensation. abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a Amendment VI. In all criminal prosecutions the accused redress of grievances. shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been Amendment II. A well-regulated militia being necessary to committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; arms shall not be infringed. to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtain-ing witnesses in his favor, and to have the Amendment III. No soldier shall, in time of peace, be assistance of counsel for his defense. quartered in any house, without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law. -

What You Can Do During Pregnancy to Prepare for Breastfeeding

What You Can Do During Pregnancy to Prepare for Breastfeeding As a woman, your body is already prepared for breastfeeding. Rest assured that you can produce breast milk. The guidelines below may help you feel ready for breastfeeding. • Attend a breastfeeding class. If possible, bring along those who are going to support you. What you learn can help you to be more confident and to know if and when you need help. • You will probably have some breast tenderness and may see your breasts grow larger during pregnancy. Let your health care provider or breastfeeding resource person know if you have had any kind of breast surgery. • Look at your breasts. Are your nipples usually erect, flat or inverted? (See the diagrams below.) Do they stand out when touched or cold? If your nipples are flat or inverted, or if you’re not sure, ask your health care provider or breastfeeding resource person for information to help you get ready for breastfeeding. Flat or inverted nipples will not prevent you from breastfeeding. Erect nipples Flat nipples Inverted nipples stand out from form a smooth sink into the full the breast. line with the part of the breast rest of the and may form a breast. “dimple.” Check your wardrobe for clothing that will be loose-fitting, comfortable, and easy to adjust when breastfeeding your baby. There is no need to buy special clothing. • Try not to apply soap or lotion directly to your nipples; use clear water for washing. If the area around your nipples is very dry, talk with your breastfeeding resource person. -

Post-Delivery Instructions San Diego Perinatal Center 8010 Frost Street, Suite 300 San Diego, CA 92123

Post-Delivery Instructions San Diego Perinatal Center 8010 Frost Street, Suite 300 San Diego, CA 92123 ACTIVITY: Physical activity folate and iron. from the shower run over should be as you can tolerate. them for a long time. Allow for rest periods, NURSING MOTHERS: If Stimulation of any kind especially the first 2 weeks. If nipples become sore or cause more milk production. you would like to exercise - cracked: It can produce temporary walking is recommended. 1. Expose nipples to air as relief but not long term Jogging and swimming are much as possible. The flaps relief. If breasts become okay after 6 weeks. Do not of your nursing bra can be painful and firm: return to full activity left open when leaking is not 1. Decrease your fluid (aerobics, tennis, a problem. intake. employment) until after your 2. Wash nipples only with 2. Apply an ice bag wrapped postpartum check-up -- and water. Other cleansing in a thin towel to the no sit-ups or weight lifting for products are unnecessary, breasts. at least 3 months after a and may taste bad leading to 3. Two Aspirins or Advil cesarean, until your scar has improper suckling. may be taken very 4 hours if healed to a thin white line. 3. Use breast milk to needed. lubricate nipples after 4. Cold cabbage leaves (not SLEEP: Make sure to get feeding. cooked) tucked inside bra. adequate rest. Your baby 4. A commercial product will wake you a lot at night, such as unmedicated lanolin BREAST INFECTION so try to nap while baby is should be used (Mastitis): Can occur sleeping during the day. -

A Cognitive Approach in Combating the Lies Christian Males Believe

i LIBERTY BAPTIST THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PORNOGRAPHY ADDICTION: A COGNITIVE APPROACH IN COMBATING THE LIES CHRISTIAN MALES BELIEVE DOCTOR OF MINISTRY PROJECT A Thesis Project Submitted to Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF MINISTRY By Farid Awad Fayetteville, North Carolina April, 2010 ii Copyright 2010 Farid Awad All Rights Reserved iii LIBERTY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY THESIS PROJECT APPROVAL SHEET ______________________________ GRADE ______________________________ MENTOR ______________________________ READER iv ABSTRACT PORNOGRAPHY ADDICTION: A COGNITIVE APPROACH IN COMBATING THE LIES CHRISTIAN MALES BELIEVE Farid Awad Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary, 2010 Mentor: Dr. Charlie Davidson Pornography addiction has grown in epidemic numbers. Its bondage is evident within and outside the church walls. While sex and sexually explicit images saturate our daily lives, God continues to call His people to be holy as He is holy. Freedom from pornography addiction can be achieved only through intimate relationship with Jesus Christ and by accepting the atoning work of His cross for all believers. This thesis will redefine pornography through the lens of the Scripture and primarily focus on cognitive lies regarding oneself and others, which are crippling and ensnaring men into the trap of pornography. This study seeks to expose and correct such lies through God’s Word. This inward/outward approach provides the premises for a lifelong genuine change. Abstract length: 121 words v CONTENTS INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….... 1 CHAPTER ONE: CHALLENGES OF PORNOGRAPHY…………………...… 12 Search for Definition…………………………………………………..… 13 Historical Perspective and Current Severity……………………………... 22 Biblical Perspective………………………………………………………. 33 CHAPTER TWO: UNDERSTANDING ADDICTION……………………...…. 44 From Casual to Bondage…………………………………………...…….. 44 Beyond Addiction……………………………………………..……...…... 57 CHAPTER THREE: STEP ONE TO RECOVERY – INWARD HEALING…... -

Playing by Pornography's Rules: the Regulation of Sexual Expression

PLAYING BY PORNOGRAPHY'S RULES: THE REGULATION OF SEXUAL EXPRESSION DAVID COLEt INTRODUCTION Sometimes a sentence is worth a thousand words. In 1964, as the Supreme Court stumbled toward a constitutional approach to obscenity, Justice Potter Stewart suggested that only "hard-core pornography" should be suppressed.' He admitted that the category may be incapable of "intelligibl[e]" definition, but 2 nonetheless confidently asserted, "I know it when I see it." Justice Stewart's sentence captures the essence of the Court's sexual expression jurisprudence, which rests more on the assertion of distinctions than on reasoned analysis. For many years, the Court, unable to agree upon a doctrinal framework for obscenity regulation, simply ruled by per curiam judgments, without offering any explanation for what it was doing.' When the Court did attempt to explain its actions, some suggested that it would have been better off maintaining its silence.' The Court has now put forward a set of doctrinal "rules" that in the end do little more than obscure what is basically Stewart's intuitive approach. In defining obscenity, the Court has advanced an incoherent formula that requires the application of "community t Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. I would like to thank Craig Bloom, Adam Breznick, Anne Dailey, Jonathan Elmer, Bill Eskridge, Cindy Estlund, Marjorie Heins, Ellen Hertz, Sam Issacharoff, Jules Lobel, Carlin Meyer, David Myers, Dan Ortiz, Gary Peller, Nina Pillard, Larry Rosen, Mike Seidman, Nomi Stolzenberg, Nadine Strossen, Mark Tushnet, Suzanne Underwald, and Franz Werro for their helpful comments and suggestions on various drafts. I was or am counsel for plaintiffs in Finley v.