North Carolina Guide for the Early Years: Second Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NHANES 2015-2016 MEC In-Person Dietary Interviewers Procedures

MEC In-Person Dietary Interviewers Procedures Manual January 2016 Table of Contents Chapter Page 1 Introduction to the Dietary Interview ............................................................. 1-1 1.1 Dietary Interview Component in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey ............................................................ 1-1 1.2 The Role of the Dietary Interviewer .................................................. 1-3 1.3 Other Duties of the Dietary Interviewer ........................................... 1-4 1.4 Observers and MEC Visitors .............................................................. 1-5 2 Equipment, Supplies, and Materials ................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Description of the MEC Interview Room and Equipment ............ 2-1 2.2 MEC Interview Supplies and Other Equipment .............................. 2-1 2.2.1 Measuring Guides ................................................................. 2-1 2.3 MEC Dietary Interviewer Materials ................................................... 2-3 2.3.1 Hand Cards ............................................................................ 2-3 2.3.2 Reminder Cards .................................................................... 2-4 2.3.3 Measuring Guide Package ................................................... 2-4 2.4 Equipment Setup and Teardown Procedures ................................... 2-4 2.4.1 MEC Dietary Interview Room Setup Procedures ........... 2-4 2.4.2 MEC Dietary Interview Room Teardown -

Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020

k Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020 For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk CONTENTS 5 USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS 5 EXPLANATION OF KASHRUT SYMBOLS 5 PROBLEMATIC E NUMBERS 6 BISCUITS 6 BREAD 7 CHOCOLATE & SWEET SPREADS 7 CONFECTIONERY 18 CRACKERS, RICE & CORN CAKES 18 CRISPS & SNACKS 20 DESSERTS 21 ENERGY & PROTEIN SNACKS 22 ENERGY DRINKS 23 FRUIT SNACKS 24 HOT CHOCOLATE & MALTED DRINKS 24 ICE CREAM CONES & WAFERS 25 ICE CREAMS, LOLLIES & SORBET 29 MILK SHAKES & MIXES 30 NUTS & SEEDS 31 PEANUT BUTTER & MARMITE 31 POPCORN 31 SNACK BARS 34 SOFT DRINKS 42 SUGAR FREE CONFECTIONERY 43 SYRUPS & TOPPINGS 43 YOGHURT DRINKS 44 YOGHURTS & DAIRY DESSERTS The information in this guide is only applicable to products made for the UK market. All details are correct at the time of going to press but are subject to change. For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk. Sign up for email alerts and updates on www.kosher.org.uk or join Facebook KLBD Kosher Direct. No assumptions should be made about the kosher status of products not listed, even if others in the range are approved or certified. It is preferable, whenever possible, to buy products made under Rabbinical supervision. WARNING: The designation ‘Parev’ does not guarantee that a product is suitable for those with dairy or lactose intolerance. WARNING: The ‘Nut Free’ symbol is displayed next to a product based on information from manufacturers. The KLBD takes no responsibility for this designation. You are advised to check the allergen information on each product. k GUESS WHAT'S IN YOUR FOOD k USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS Hi Noshers! PRODUCTS WHICH ARE KLBD CERTIFIED Even in these difficult times, and perhaps now more than ever, Like many kashrut authorities around the world, the KLBD uses the American we need our Nosh! kosher logo system. -

LICENCE to RESCUE We Meet the Tireless Volunteers Whose Airborne Support Comes from RAF Search and Rescue

EASTERN AIRWAYS IN-FLIGHT 44 | Summer 2013 LICENCE TO RESCUE We meet the tireless volunteers whose airborne support comes from RAF Search and Rescue ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: NORDIC NOIR TRANSLATED WORDSWORTH’S LAKE DISTRICT DESTINATION OFFSHORE EUROPE SUPPLEMENT This is your complimentary in-flight magazine, to read now or to take home WELCOME Welcome to the Eastern Airways Magazine – please feel free to take it away with you and pass it round your family and friends! This issue includes our special preview supplement for the so-called Gem Towns. Victoria Gibson samples the the forthcoming Offshore Europe 2013 exhibition and life of the mountain rescue volunteers and we make conference in Aberdeen, when so many of the movers a flying visit to Robin Hood Country… and the hairy and shakers in this hugely important industry will get mammoths that once lived there! together. Eastern Airways is one of those industry players, thanks to our many strategic connections from There’s the chance to win dinner and a two-day break at around the UK and Norway to the UK oil and offshore the country house home of Scotland’s “best chef” and capital. our regular Puzzle Page, with its best English whisky prize. Of course, through our relationship with Emirates airline, we provide links between Aberdeen and the oil centres We hope the Eastern Airways Magazine reflects our core of the Middle East via Emirates’ Dubai services at values of punctuality, reliability and convenience. We Newcastle. aspire to quality service and attention to detail, starting with selecting your flight, and continuing through fast- But the magazine is about far more than the offshore track security at many airports, business lounge access sector – in this issue we talk to the “actor of the for customers on flexible tickets and high quality service moment”, TV detective, MP and former Dr Who, David on board punctual, reliable flights. -

These Vegans Really Believe Animal Crackers Are 'Problematic' - MUNCHIES

11/30/2018 These Vegans Really Believe Animal Crackers Are 'Problematic' - MUNCHIES Recipes Booze Culture Restaurants WTF SNACKS These Vegans Really Believe Animal Crackers Are 'Problematic' "[T]he phenomenon of animal crackers remains problematic and part of a wider culture of speciesism.” By Karen Chernick | Sep 24 2018, 3:00pm Photo via Getty Images // iStock SHARE TWEET Plentyyggjygg of otherwise animal-abstaining vegans enjoy biting into a gorilla now and then, UPsavoring NEXT a crunchy loophole in an otherwise firm abstention from eating animals.20 of That the Best loophole Snacks is to the Eat animal While Stoned cracker: iconic, beloved by children, and, conveniently, largely a plant-based treat. https://munchies.vice.com/en_us/article/43837d/these-vegans-really-believe-animal-crackers-are-problematic 1/21 11/30/2018 These Vegans Really Believe Animal Crackers Are 'Problematic' - MUNCHIES Trader Joe’s, Costco, and Whole Foods all sell their own brands of vegan animal Recipes Booze Culture Restaurants WTF crackers; Barbara’s Snackimals and Stauffer’s are likewise free of eggs and dairy. Nabisco,bi arguably bl the h most well-known ll k animal i l cracker k variety, i is i not only l vegan but b scored extra points with animal rights activists last month when it released its lions, tigers, and bears from their century-long cage captivity on the snack’s packaging. Cages linked the morsels with the circus industry, and in a letter PETA urged Nabisco to update the snack’s graphics “given the egregious cruelty inherent in circuses” towards four-legged friends. The company acquiesced, a visual tradition that began in 1902 came to a halt, and numerous headlines ensued. -

Kids' Fruits & Veggies Recipe Contest Cookbook

Kids’ Fruits & Veggies Recipe Contest Cookbook 2007-2008 ABout The Contest The 2007-2008 school year marks the 6th successful year of the Kids’ Fruits & Veggies Recipe Contest. The contest is hosted by the Utah Depart- ment of Health and our Utah Fruits & Veggies–More Matters® Association partners. Our cookbook has a new name this year, with 5 A Day replaced by Fruits & Veggies–More Matters®. We received 77 entries this year! Winners were selected in each of the seven categories: Breakfast Item, Snack, Salad, Smoothie, Creative, Des- sert, and Main Dish. Recipes were judged by members of the Fruits & Veggies–More Matters Association who put their taste buds to the test scoring recipes for ease of preparation, creativity, and taste! All recipes were judged for health benefi t by dietetic interns from Brigham Young University. Winning recipes had to be healthy, tasty, contain no more than 12 readily available ingredients, and be easy to prepare in about 20 minutes. Our winners receive some great prizes and a certifi cate presented to them at school. They also get the chance to be on TV and on the Web. The idea behind the contest is that kids will discover the fun of cooking with fruits and vegetables early on. You will fi nd all of the 2007-2008 entries in this cookbook. We hope you enjoy! *Special thanks to all of our judges, partici- pants and their parents, and contest organiz- ers, including the Utah Fruits & Veggies–More Kate with Casey Scott, making Matters Association. her Creamy Dreamy Fruit Cup. i Table of Contents Breakfast Items Main Dishes Strawberry & Banana SpaghettiS Squash Super ............... -

Route Catalog

Current as of Wednesday, January 06, 2010 Product Catalog Dixon, IL 61021 Your Area Restaurant, Event and Bar Supplier (815) 288-6747 Fax: (815) 288-1131 Email: [email protected] www.astroven.net This catalog is a listing of all regular stocked products. Because many products are affected by daily market changes, no pricing is included in this catalog. For pricing information, please call (815) 288-6747 and ask to speak to a customer service representative. This catalog does not include special order items. 1/6/2010 ASTRO-VEN DISTRIBUTORS - PRODUCT CATALOG Page 1 of 25 ASTRO-VEN DISTRIBTORS-PRODUCT CATALOG PRICES SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITH MARKET CONDITIONS. AEROSOLS 340027 LW Batt Mozzarella Sticks 2# 6 010078 Cracker Amer Fav Asst. 2PK 500 ITEMDESCRIPTION SIZE 240205 Fernando Mini Tacos 320ct 1 010173 VDF Puff Pastry 18 Sheets 18 060507 Foaming Germicidal Clnr 19o 1 AUTOMOTIVE 010065 Keebler Honey Grahams 16o 12 060516 IndCom Furniture Polish 19o 6 ITEMDESCRIPTION SIZE 010066 Keebler Frstd Animal Cracker 96 060514 Stainless Cleaner 15oz Aero 6 060035 Polar Washer Fluid -20 6 010085 White Choc.Rasp Cheese Ca 12 060513 Stainless Steel Polish 16oz 6 BACON 010150 Kellogg Nutri-Grain AppleCin 8 060512 SprayWOW Foaming Clnr 15 1 ITEMDESCRIPTION SIZE 010044 Sunshine Oyster Crackers I 150 060510 Disinfectant Cleaner 19oz 6 120124 15# 14/18 Bacon Grill Ready box 010043 Saltine Cracker 2pk 500 060508 Devere Food Equip Clnr 18oz 1 120240 HM Jalapeno Bacon 300SL 1 010041 Nab Cinn Teddy Grahams 1. 48 060517 Disinfectant Deod 15.5oz 6 120105 12# 18/22 HM Hotel Bacon 1 010160 Kellogg Nutri-Grain Aple/Cin 16 060506 Food Equip. -

Animal Cracker Biomes Directions

Activity Title: Animal Cracker Biomes Suggested Season: Any Suggested Grade Level: K-5 Objective: Identify what biomes animals live in Indoors or Outdoors: Indoors Time: 10-15 minutes Theme: Biomes Materials Needed: Animal crackers; color copies of Biome Posters Topic: Animal Biomes (Blackline master on CD) for each small group Directions: 1. Divide students into small groups of 4 or 5. 2. Give each group a box or bowl of animal crackers and a set of biome posters. 3. Have students sort the animal crackers into the biome where they belong. 4. Have groups check each other for accuracy and discuss any differences they find. Discussion Questions: 1. Why do animals belong to a particular biome? Why can’t they live anywhere? 2. What differences did you notice when checking other groups? Variation(s): Math Extension- Students can create a graph based on how many animals were placed in each biome. Created by Bonnie Fahning, 2010, ISD #719 Standards Addressed: Science: 1.4.1.1.1.; 1.4.2.1.1.; 1.4.2.1.2.; 3.1.1.1.1.; 3.4.3.2.2.; 5.4.1.1.1.; 5.4.2.1.2.; 6.1.3.1.1. Language Arts: K.I.B.; K.II.B.; K.III.A.; 1.III.A.; 1.III.B.1.; 2.III.A.; 3.1.B.1.; 3.III.A.2.; 4.1.B.1.; 5.I.B.; 5.III.A.1.; 5.III.A.2.; 5.III.A.3.; 5.III.A.4. Math: Social Studies: Background Information: • Tundra: This biome is characterized by an extremely cold climate. -

Long Live the Queen

A PUBLICATION OF WILLY STREET CO-OP, MADISON, WI VOLUME 46 • ISSUE 6 • JUNE 2019 LONG LIVE THE QUEEN STORES CLOSING EARLY Sunday, June 30 at 7:30pm for our year-end inventory count PAID PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. POSTAGE POSTAGE U.S. MADISON, WI MADISON, PERMIT NO. 1723 NO. PERMIT 1457 E. Washington Ave • Madison, WI 53703 Ave 1457 E. Washington POSTMASTER: DATED MATERIAL POSTMASTER: DATED CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED CHANGE SERVICE WILLY STREET CO-OP MISSION STATEMENT The Williamson Street Grocery Co-op is an economically and READER environmentally sustainable, cooperatively owned grocery PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY WILLY STREET CO-OP business that serves the needs of its Owners and employ- East: 1221 Williamson Street, Madison, WI 53703, 608-251-6776 ees. We are a cornerstone West: 6825 University Ave, Middleton, WI 53562, 608-284-7800 of a vibrant community in south-central Wisconsin that North: 2817 N. Sherman Ave, Madison, WI 53704, 608-471-4422 provides fairly priced goods Central Office: 1457 E. Washington Ave, Madison, WI 53703, 608-251-0884 and services while supporting EDITOR & LAYOUT: Liz Wermcrantz local and organic suppliers. ADVERTISING: Liz Wermcrantz COVER DESIGN: Hallie Zillman SALE FLYER DESIGN: Hallie Zillman GRAPHICS: Hallie Zillman WILLY STREET CO-OP SALE FLYER LAYOUT: Liz Wermcrantz BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRINTING: Wingra Printing Group The Willy Street Co-op Reader is the monthly communications link among the Jeannine Bindl, President Co-op Board, staff and Owners. It provides information about the Co-op’s services Meghan Gauger, and business as well as about cooking, nutrition, health, sustainable agriculture and Vice President more. -

Nut Free, Dairy-Free, Egg-Free Snacks

NUT FREE, DAIRY-FREE, EGG-FREE SNACKS Kellogg's Froot Loops Enjoy Life Brand Foods Motts Applesauce Kellogg's Crispix Frito Corn Chips Musselman's Applesauce Kellogg's Honey Smacks Pringles Chips Original PopTarts--Strawberry, cherry Kellogg's Frosted Mini Wheats Saltine Crackers Blueberry Cinnamon Roll, frosted, chocolate, strawberry, blueberry Act II Butter lovers Micro Popcor Brown sugar Cinnamon Kellogg's Cookie Crunch Rold Gold Pretzel Sticks Slim Jims Kellogg's Apple Jacks CANDY Joy Ice Cream Cones Kellogg's Corn Pops Wonka Battle Caps Skinny Pop Kellogg's Cinnabon Ceral Wonka Laffy Taffy Quaker Rice Cakes GM-CocoaPuffs Small ones-Not Chocolate Nabisco Belvita Breakfast Biscuits GM-Cheerios: originial Wonka Sweettarts-not chewy Fresh Fruit Multi grain,chocolate, fruity Wonka Tart N Tiny Fresh Veggies GM-Kix Wonka Tixy Stix Betty Crocker Fruit Roll Ups GM-Cookie Crisp Wonka Candy Canes GM-Trix Wonka Runts GM-Lucky Charms Air Heads-not chocolate GM-Cinnamon Toast Crunch Skittles Quaker-Life Dots Quaker Oatmeal squares Jolly Ranchers Quaker- Cap'n Crunch Tic Tac Mints & Orange Flavor with or without berries Just Borne Jelly Beans Keebler Wheatables Brach's Small Conversation Hearts Keebler Town House Good & Plenty Keebler Vienna Fingers Mike & Ike Nabisco Vegetable Thins Crackers Dum Dum Lolipops Nabisco Teddy Grahams Swedish fish Nabisco Honey Maid Graham Stics Smarties Nabisco BARNUM'S Animal Cracker Life Savers Nabisco Fig Newtons(orig/Strawberr Star Burst Oreos (Not Peanut Butter) Jet Puffed Marshmallows Nabisco Ritz Crackers Cake Mate Decorating Sugar Original/Whole Wheat Cake Mate Writing icing Nabisco 100 Cal. Oreo Thin Crisps Pillsbury Easy Frost Spray Frosting Nabisco 100 cal. -

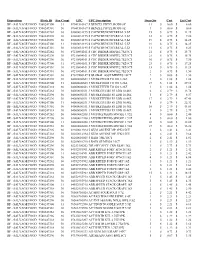

Disposition Block ID Box Count UPC UPC Description Item Qty Cost Ext

Disposition Block ID Box Count UPC UPC Description Item Qty Cost Ext Cost RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247300 31 07041510167 $ BENZEL PRTZL RODS 8Z 11 $ 0.60 $ 6.60 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247301 30 07041510167 $ BENZEL PRTZL RODS 8Z 1 $ 0.60 $ 0.60 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247262 30 03000031195 $ CAPNCRUNCHCEREAL 5.5Z 15 $ 0.75 $ 11.25 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247290 30 03000031195 $ CAPNCRUNCHCEREAL 5.5Z 12 $ 0.75 $ 9.00 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247296 30 03000031195 $ CAPNCRUNCHCEREAL 5.5Z 19 $ 0.75 $ 14.25 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247300 31 03000031195 $ CAPNCRUNCHCEREAL 5.5Z 19 $ 0.75 $ 14.25 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247301 30 03000031195 $ CAPNCRUNCHCEREAL 5.5Z 11 $ 0.75 $ 8.25 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247262 30 07210854101 $ CHC DBDKR MNPIE2.75Z/3CT 21 $ 0.75 $ 15.75 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247290 30 07210854101 $ CHC DBDKR MNPIE2.75Z/3CT 21 $ 0.75 $ 15.75 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247296 30 07210854101 $ CHC DBDKR MNPIE2.75Z/3CT 10 $ 0.75 $ 7.50 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247300 31 07210854101 $ CHC DBDKR MNPIE2.75Z/3CT 23 $ 0.75 $ 17.25 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247301 30 07210854101 $ CHC DBDKR MNPIE2.75Z/3CT 15 $ 0.75 $ 11.25 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247318 30 07210854101 $ CHC DBDKR MNPIE2.75Z/3CT 2 $ 0.75 $ 1.50 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247301 30 87627400147 $ GLOBAL ASST MINEES 10CT 2 $ 0.68 $ 1.36 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247296 30 04000000603 3 MUSKETEER TO GO 3.28Z 1 $ 1.08 $ 1.08 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247300 31 04000000603 3 MUSKETEER TO GO 3.28Z 27 $ 1.08 $ 29.16 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247318 30 04000000603 3 MUSKETEER TO GO 3.28Z 1 $ 1.08 $ 1.08 RF - SALVAGE FOOD 9580247262 -

ACTIVITY CARDS 24-36 Months

ACTIVITY CARDS 24-36 months These cards are designed for teachers of two-year-olds Georgia Early Learning and Development Standards gelds.decal.ga.gov Georgia Early Learning and Development Standards gelds.decal.ga.gov /64 33 57/64 14 9 5 32 /64 1 33 5/64 23 /4 14 /64 32 <<---Grain--->> decal.ga.gov 2 57/64 dards Teacher an Toolbox ent St pm / rly Learning and Develo 64 Ea ia 17 eorg 8 Activities based on the GeorgiaG Early Learning and Development Standards 4 gelds.decal.ga.gov 8-17/64") 1/4 Bleed 23 INDEX YOUR OWN ACTIVITIES COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT Cover:SOCIAL STUDIES | SS8-57/64 x 4-17/64 x 2" BRIGHT IDEAS COGNITIVEWrap: 14-33/64 x 9-57/64" DEVELOPMENTMATH | MA Teacher Toolbox Activities17 based onCOGNITIVE the Georgia Early Learning and Development Standards Liner: None / DEVELOPMENTC0GNITIVE 4 64 PROCESSES | CP COMMUNICATION,LANGUAGE Blank: .080 w1s (12-57/64 x 57 AND LITERACY | CLL / Georgi a Early Learning and Developm COGNITIVE ent Standards 64 gelds.decal.ga.gov 9 DEVELOPMENT CREATIVE 57 decal.ga.gov Post production die cut DEVELOPMENT | CR APPROACHESTO PLAY /64 8AND LEARNING | APL COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT SCIENCE | SC SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL DEVELOPMENT | SED SCHOOL PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT AND MOTOR SKILLS | PDM Bleed 2 and Development Standards Activities based on the Georgia Early Learning side Post production die cut <<---Grain--->> ndards t Sta en opm vel rning and De ea rly L eorgia Ea 22.247 G gelds.decal.ga.gov decal.ga.gov D Cover: 8-57/64 x 4-17/64 x 2" 4 Base: 8-5/8Wrap: x 4 x 6-1/2" 14-33/64 x 9-57/64" 5/ 4 Wrap: 23-1/4 x 18-5/8" 18 8 5 Liner: None /8 Liner: None D d 8 ecal. -

CADBURY 2017 Fact Sheet

2017 Fact Sheet One of the World’s Favorite Chocolate Brands Cadbury chocolate is one of the world’s best-selling brands, with more than $3 billion in net revenues in 2016. But it didn’t become one of the world’s favorite chocolate brands overnight. It has a rich and delicious history spanning nearly 200 years, when John Cadbury opened a grocery shop in 1824 in Birmingham, U.K., selling, among other things, cocoa and drinking chocolate. We sold our first chocolate bar in 1847, our iconic Cadbury Dairy Milk was born in 1905… and we’ve been creating delicious chocolate innovations ever since! CADBURY Fun Facts: BIRTH BIGGEST MARKETS 1824 – when John Cadbury opens a grocer’s U.K., Australia, India and China. shop at 93 Bull Street, Birmingham. Among other things, he sold cocoa and drinking chocolate, which he prepared himself using a pestle and mortar. SALES RECENT COUNTRY LAUNCHES Cadbury chocolate generated more than $3 Cadbury 5Star and Cadbury Dairy Milk billion in global net revenues in 2016. OREO in various AMEA markets (2015), Cadbury Fuse in India (2016), Cadbury Dark Milk in Australia (2017). CADBURY FANS GLOBAL REACH Cadbury has nearly 1 million Facebook Cadbury chocolate can be found in more than fans, Cadbury Dairy Milk brand boasts 40 countries. more than 15 million and Cadbury Dairy Milk Silk more than 5 million! MANUFACTURING Cadbury chocolate is manufactured in more than 15 countries around the world. 2017 Fact Sheet Flavors Around the World Cadbury Dairy Milk Launched in 1905 and an instant success! Made with fresh milk from the British Isles and Fairtrade cocoa beans, Cadbury Dairy Milk remains one of the world’s top chocolate products.