Le Nozze Di Figaro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAN 10110 BOOK.Qxd 20/4/07 4:19 Pm Page 2

CHAN 10110 Front.qxd 20/4/07 4:19 pm Page 1 CHAN X10110 CHANDOS CLASSICS CHAN 10110 BOOK.qxd 20/4/07 4:19 pm Page 2 John Ireland (1879–1962) 1 Vexilla Regis (Hymn for Passion Sunday)* 11:54 2 Greater Love Hath No Man† 6:51 3 These Things Shall Be‡ 22:12 Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht 4 A London Overture 13:36 5 The Holy Boy (A Carol of the Nativity) 2:43 6 Epic March 9:13 TT 67:11 Paula Bott soprano*† Teresa Shaw contralto* James Oxley tenor* Bryn Terfel bass-baritone*†‡ Roderick Elms organ* London Symphony Chorus*†‡ John Ireland London Symphony Orchestra Richard Hickox 3 CHAN 10110 BOOK.qxd 20/4/07 4:19 pm Page 4 and Friday before Easter – and what we cannot sketch was ready during April. Ireland Ireland: Orchestral and Choral Works have – the ceremonies on the Saturday before remarked that he felt the words were ‘an Easter as practised by the Roman Church – expression of British national feeling at the something absolutely agelong & from present time’. In fact he had earlier made a John Nicholson Ireland was born near nineteen-year-old Ireland was then still a everlasting – the rekindling of Fire – Lumen quite different setting of these words for Manchester and spent most of his life in student of Stanford’s, and was assistant Christi. The Motherland Song Book published in London, though with interludes in the Channel organist at Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Square, 1919. The composer made a few adjustments Islands and Sussex. His was a life of restricted London. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

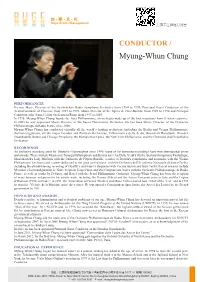

Myung-Whun Chung

如 • 歌 • 文 • 化 Ruge Artists Management 扫描关注微信订阅号 CONDUCTOR / Myung-Whun Chung PERFORMANCES He was Music Director of the Saarbrücken Radio Symphony Orchestra from 1984 to 1990, Principal Guest Conductor of the TeatroComunale of Florence from 1987 to 1992, Music Director of the Opéra de Paris-Bastille from 1989 to 1994 and Principal Conductor atthe Santa Cecilia Orchestra in Rome from 1997 to 2005. In 1995, Myung-Whun Chung founds the Asia Philharmonic, an orchestra made up of the best musicians from 8 Asian countries. In 2005,he was appointed Music Director of the Seoul Philarmonic Orchestra. He has been Music Director of the Orchestre Philharmonique deRadio France since 2000. Myung-Whun Chung has conducted virtually all the world’s leading orchestras, including the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic, theConcertgebouw, all the major London and Parisian Orchestras, Filharmonica della Scala, Bayerisch Rundfunk, Dresden Staatskapelle,Boston and Chicago Symphony, the Metropolitan Opera, the New York Philharmonic and the Cleveland and Philadelphia Orchestras. RECORDINGS An exclusive recording artist for Deutsche Grammophon since 1990, many of his numerous recordings have won international prizes and awards. These include Messiaen's TurangalîlaSymphony and Eclairs sur l’Au-Delà, Verdi's Otello, Berlioz'sSymphonie Fantastique, Shostakovich's Lady Macbeth with the Orchestre de l'Opéra Bastille; a series of Dvorák's symphonies and serenades with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and a series dedicated to the great sacred music with the Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, including the award-winning recording of Duruflé’s and Fauré’s Requiems with Cecilia Bartoli and Bryn Terfel. Recent releases include Messiaen’s La transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ and Des Canyons aux étoiles with the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France as well as works by Debussy and Ravel with the Seoul Philharmonic Orchestra. -

Marie Collier: a Life

Marie Collier: a life Kim Kemmis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The University of Sydney 2018 Figure 1. Publicity photo: the housewife diva, 3 July 1965 (Alamy) i Abstract The Australian soprano Marie Collier (1927-1971) is generally remembered for two things: for her performance of the title role in Puccini’s Tosca, especially when she replaced the controversial singer Maria Callas at late notice in 1965; and her tragic death in a fall from a window at the age of forty-four. The focus on Tosca, and the mythology that has grown around the manner of her death, have obscured Collier’s considerable achievements. She sang traditional repertoire with great success in the major opera houses of Europe, North and South America and Australia, and became celebrated for her pioneering performances of twentieth-century works now regularly performed alongside the traditional canon. Collier’s experiences reveal much about post-World War II Australian identity and cultural values, about the ways in which the making of opera changed throughout the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and how women negotiated their changing status and prospects through that period. She exercised her profession in an era when the opera industry became globalised, creating and controlling an image of herself as the ‘housewife-diva’, maintaining her identity as an Australian artist on the international scene, and developing a successful career at the highest level of her artform while creating a fulfilling home life. This study considers the circumstances and mythology of Marie Collier’s death, but more importantly shows her as a woman of the mid-twentieth century navigating the professional and personal spheres to achieve her vision of a life that included art, work and family. -

28Apr2004p2.Pdf

144 NAXOS CATALOGUE 2004 | ALPHORN – BAROQUE ○○○○ ■ COLLECTIONS INVITATION TO THE DANCE Adam: Giselle (Acts I & II) • Delibes: Lakmé (Airs de ✦ ✦ danse) • Gounod: Faust • Ponchielli: La Gioconda ALPHORN (Dance of the Hours) • Weber: Invitation to the Dance ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Slovak RSO / Ondrej Lenárd . 8.550081 ■ ALPHORN CONCERTOS Daetwyler: Concerto for Alphorn and Orchestra • ■ RUSSIAN BALLET FAVOURITES Dialogue avec la nature for Alphorn, Piccolo and Glazunov: Raymonda (Grande valse–Pizzicato–Reprise Orchestra • Farkas: Concertino Rustico • L. Mozart: de la valse / Prélude et La Romanesca / Scène mimique / Sinfonia Pastorella Grand adagio / Grand pas espagnol) • Glière: The Red Jozsef Molnar, Alphorn / Capella Istropolitana / Slovak PO / Poppy (Coolies’ Dance / Phoenix–Adagio / Dance of the Urs Schneider . 8.555978 Chinese Women / Russian Sailors’ Dance) Khachaturian: Gayne (Sabre Dance) • Masquerade ✦ AMERICAN CLASSICS ✦ (Waltz) • Spartacus (Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia) Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet (Morning Dance / Masks / # DREAMER Dance of the Knights / Gavotte / Balcony Scene / A Portrait of Langston Hughes Romeo’s Variation / Love Dance / Act II Finale) Berger: Four Songs of Langston Hughes: Carolina Cabin Shostakovich: Age of Gold (Polka) •␣ Bonds: The Negro Speaks of Rivers • Three Dream Various artists . 8.554063 Portraits: Minstrel Man •␣ Burleigh: Lovely, Dark and Lonely One •␣ Davison: Fields of Wonder: In Time of ✦ ✦ Silver Rain •␣ Gordon: Genius Child: My People • BAROQUE Hughes: Evil • Madam and the Census Taker • My ■ BAROQUE FAVOURITES People • Negro • Sunday Morning Prophecy • Still Here J.S. Bach: ‘In dulci jubilo’, BWV 729 • ‘Nun komm, der •␣ Sylvester's Dying Bed • The Weary Blues •␣ Musto: Heiden Heiland’, BWV 659 • ‘O Haupt voll Blut und Shadow of the Blues: Island & Litany •␣ Owens: Heart on Wunden’ • Pastorale, BWV 590 • ‘Wachet auf’ (Cantata, the Wall: Heart •␣ Price: Song to the Dark Virgin BWV 140, No. -

Mozart's Operas, Musical Plays & Dramatic Cantatas

Mozart’s Operas, Musical Plays & Dramatic Cantatas Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebotes (The Obligation of the First and Foremost Commandment) Premiere: March 12, 1767, Archbishop’s Palace, Salzburg Apollo et Hyacinthus (Apollo and Hyacinth) Premiere: May 13, 1767, Great Hall, University of Salzburg Bastien und Bastienne (Bastien and Bastienne) Unconfirmed premiere: Oct. 1768, Vienna (in garden of Dr Franz Mesmer) First confirmed performance: Oct. 2, 1890, Architektenhaus, Berlin La finta semplice (The Feigned Simpleton) Premiere: May 1, 1769, Archbishop’s Palace, Salzburg Mitridate, rè di Ponto (Mithridates, King of Pontus) Premiere: Dec. 26, 1770, Teatro Regio Ducal, Milan Ascanio in Alba (Ascanius in Alba) Premiere: Oct. 17, 1771, Teatro Regio Ducal, Milan Il sogno di Scipione (Scipio's Dream) Premiere: May 1, 1772, Archbishop’s Residence, Salzburg Lucio Silla (Lucius Sillus) Premiere: Dec. 26, 1772, Teatro Regio Ducal, Milan La finta giardiniera (The Pretend Garden-Maid) Premiere: Jan. 13, 1775, Redoutensaal, Munich Il rè pastore (The Shepherd King) Premiere: April 23, 1775, Archbishop’s Palace, Salzburg Thamos, König in Ägypten (Thamos, King of Egypt) Premiere (with 2 choruses): Apr. 4, 1774, Kärntnertor Theatre, Vienna First complete performance: 1779-1780, Salzburg Idomeneo, rè di Creta (Idomeneo, King of Crete) Premiere: Jan. 29, 1781, Court Theatre (now Cuvilliés Theatre), Munich Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) Premiere: July 16, 1782, Burgtheater, Vienna Lo sposo deluso (The Deluded Bridegroom) Composed: 1784, but the opera was never completed *Not performed during Mozart’s lifetime Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario) Premiere: Feb. 7, 1786, Palace of Schönbrunn, Vienna Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) Premiere: May 1, 1786, Burgtheater, Vienna Don Giovanni (Don Juan) Premiere: Oct. -

20 Singers from 15 Countries Announced for BBC Cardiff Singer of the World 2019 15-22 June 2019

20 singers from 15 countries announced for BBC Cardiff Singer of the World 2019 15-22 June 2019 • 20 of the world’s best young singers to compete in the 36th year of the BBC's premier voice competition • Competitors come from 15 countries, including three from Russia, two each from South Korea, Ukraine and USA, and one each from Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China, England, Guatemala (for the first time), Mexico, Mongolia, Portugal, South Africa and Wales • Extensive broadcast coverage across BBC platforms includes more LIVE TV coverage than ever before • High-level jury includes performers José Cura, Robert Holl, Dame Felicity Lott, Malcolm Martineau, Frederica von Stade alongside leading professionals David Pountney, John Gilhooly and Wasfi Kani • Value of cash prizes increased to £20,000 for the Main Prize and £10,000 for Song Prize, thanks to support from Kiri Te Kanawa Foundation • Song Prize trophy to be renamed the Patron’s Cup in recognition of this support • Audience Prize this year to be dedicated to the memory of much-missed baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky, winner of BBC Cardiff Singer of the World in 1989, who died in 2017 • New partnership with Wigmore Hall sees all Song Prize finalists offered debut concert recitals in London’s prestigious venue, while Main Prize to be awarded a Queen Elizabeth Hall recital at London’s Southbank Centre Twenty of the world’s most outstanding classical singers are today [4 March 2019] announced for BBC Cardiff Singer of the World 2019. The biennial competition returns to Cardiff between 15-22 June 2019 and audiences in the UK and beyond can follow all the live drama of the competition on BBC TV, radio and online. -

Overture to the Marriage of Figaro

Integrated subject areas: Music English Language Arts Overture to The Marriage Social Emotional Learning of Figaro: Compare and Grade(s): 4-6 Lesson length: 40 minutes Contrast Instructional objectives: Students will: Learn about Mozart’s life DESCRIPTION Identify basic musical elements: tempo, dynamics, instrumentation and melody Compare and contrast two different musical styles using Students will listen to two pieces of music with similar melodies, but in the same basic melody completely different styles. One piece is the overture to The Marriage of Compose a review as a music Figaro, an opera in four acts written by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in 1786. critic The other is a modern interpretation of the same piece of music by the East Village Opera Company. Materials: Musical recordings of the Students will explore instrumentation, tempo, dynamics, and style used featured repertoire listed within these two pieces. above Sound system for musical Assessment Strategies excerpts of concert repertoire (e.g. laptop and speakers, In this lesson, students should be able to successfully do the following: iPhone® dock, Spotify®, etc) discuss basic musical elements such as tempo, dynamics, instrumentation Paper and writing utensil and melody; differentiate between two musical works with the same melody but very different styles, through class discussion and a writing Featured Repertoire*: assignment. Learn more about assessment strategies on page 5. Mozart – Overture to The Marriage of Figaro Learning Standards East Village Opera Company – Overture Redux (Le Nozze Di This lesson uses Common Core and National Core Arts Anchor Figaro) Standards. You can find more information about the standards featured in this lesson on page 4. -

CHAN 3093 BOOK.Qxd 11/4/07 3:30 Pm Page 2

CHAN 3093 Book Cover.qxd 11/4/07 3:23 pm Page 1 GREAT OPERATIC ARIAS GREAT OPERATIC ARIAS CHAN 3093 CHANDOS O PERA IN DIANA MONTAGUE ENGLISH 2 PETER MOORES FOUNDATION CHAN 3093 BOOK.qxd 11/4/07 3:30 pm Page 2 Diana Montague at the recording sessions Cooper Bill Great Operatic Arias with Diana Montague 3 CHAN 3093 BOOK.qxd 11/4/07 3:30 pm Page 4 Time Page Time Page Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) from Atalanta from The Marriage of Figaro Meleagro’s aria (Care selve) Cherubino’s Aria (Non so più) 6 ‘Noble forests, sombre and shady’ 2:05 [p. 46] Alastair Young harpsichord • Susanne Beer cello 1 ‘Is it pain, is it pleasure that fills me’ 3:07 [p. 44] from The Clemency of Titus Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sextus’s Aria (Parto, parto) from Così fan tutte 2 6:39 [p. 44] ‘Send me, but, my beloved’ Fiordiligi, Dorabella and Don Alfonso’s Trio (Soave sia il vento) Christoph Willibald von Gluck (1714–1787) 7 ‘Blow gently, you breezes’ 3:33 [p. 46] with Orla Boylan soprano • Alan Opie baritone from Iphigenia in Tauris Priestesses’ Chorus and Iphigenia’s Aria (O malheureuse Iphigénie!) Dorabella’s Recitative and Aria (Smanie implacabili) 3 ‘Farewell, beloved homeland’ – 8 ‘Ah! Leave me now’ – ‘No hope remains in my affliction’ 4:56 [p. 45] ‘Torture and agony’ 3:39 [p. 46] with Geoffrey Mitchell Choir Dorabella and Fiordiligi’s Duet (Prenderò quel brunettino) Iphigenia’s Aria (Je t’implore et je tremble) 9 ‘I will take the handsome, dark one’ 3:07 [p. -

Digital Concert Hall Where We Play Just for You

www.digital-concert-hall.com DIGITAL CONCERT HALL WHERE WE PLAY JUST FOR YOU PROGRAMME 2016/2017 Streaming Partner TRUE-TO-LIFE SOUND THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL AND INTERNET INITIATIVE JAPAN In the Digital Concert Hall, fast online access is com- Internet Initiative Japan Inc. is one of the world’s lea- bined with uncompromisingly high quality. Together ding service providers of high-resolution data stream- with its new streaming partner, Internet Initiative Japan ing. With its expertise and its excellent network Inc., these standards will also be maintained in the infrastructure, the company is an ideal partner to pro- future. The first joint project is a high-resolution audio vide online audiences with the best possible access platform which will allow music from the Berliner Phil- to the music of the Berliner Philharmoniker. harmoniker Recordings label to be played in studio quality in the Digital Concert Hall: as vivid and authen- www.digital-concert-hall.com tic as in real life. www.iij.ad.jp/en PROGRAMME 2016/2017 1 WELCOME TO THE DIGITAL CONCERT HALL In the Digital Concert Hall, you always have Another highlight is a guest appearance the best seat in the house: seven days a by Kirill Petrenko, chief conductor designate week, twenty-four hours a day. Our archive of the Berliner Philharmoniker, with Mozart’s holds over 1,000 works from all musical eras “Haffner” Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s for you to watch – from five decades of con- “Pathétique”. Opera fans are also catered for certs, from the Karajan era to today. when Simon Rattle presents concert perfor- mances of Ligeti’s Le Grand Macabre and The live broadcasts of the 2016/2017 Puccini’s Tosca. -

Noteworthy 16-2006

F.A.P. December 2OO7 Note-Worthy Music Stamps, Part 16 by Ethel Bloesch (Note: Part 16 describes stamps with musical notation that were issued in 2006.) ANTIGUA & BARBUDA Scott 2887 Michel 4353-4356 A sheet issued July 3, 2006 for the 250 th anniversary of the birth of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756- 1791). On the left side of the sheet are four stamps (three portraits of the young Mozart and a violin). The right side features a page of music superimposed on the unfinished portrait of Mozart by Joseph Lange, 1789. The music is the first page of the solo horn part to Mozart's Horn Concerto No. 3 in E-flat major, KV 447, now thought to have been written in 1787. The orchestration (clarinets and bassoons, rather than oboes and horns) and the lyrical musical style make this work more intimate and less extroverted than Mozart's three other horn concertos. ARMENIA Scott 730 Michel 540 A stamp issued March 28, 2006 for the 125 th anniversary of the birth of the Armenian musician Spiridon Melikian (1880-1933). His contributions to the musical culture of Armenia were wide- ranging: he engaged in expeditions to study Armenian folklore, wrote text-books and other musicological works, taught in the conservatory in Yerevan, and was one of the founders of the Armenian Choral Society. He also composed two children's operas, choral works, and songs. The stamp features a portrait of Melikian, with unidentified music in the background. AUSTRIA Scott 2067 Michel 2617 This stamp has been issued jointly by Austria and China on September 26, 2006. -

JC Williamson (Opera, Comic Opera, Operetta)

AUSTRALIAN EPHEMERA COLLECTION FINDING AID J.C. WILLIAMSON OPERA, COMIC OPERA, OPERETTA PROGRAMS PERFORMING ARTS PROGRAMS AND EPHEMERA (PROMPT) PRINTED AUSTRALIANA AUGUST 2017 James Cassius Williamson was an American actor who immigrated to Australia in the 1870s. Along with business partners, such as William Musgrove, his theatre company became one of the most dominant in colonial Australia. After his death in 1913 the company, now named J.C. Williamson Ltd. continued under the direction of George Tallis and the Tait brothers (who remained involved in the company until the 1970s). J.C. Williamson continued to be one of the biggest theatre companies in Australia throughout the first three quarters of the 20th century. J.C. Williamson held the license for theatres in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide and New Zealand (at times more than one theatre in each city). In 1976 the company closed, but the name was licensed until the mid 1980s. This list includes productions of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas held in J.C. Williamson theatres, as well as those produced by J.C. Williamson and performed in other theatres under venue hire arrangements. CONTENT Printed materials in the PROMPT collection include programs and printed ephemera such as brochures, leaflets, tickets, etc. Theatre programs are taken as the prime documentary evidence of a performance staged by the J.C. Williamson company. In a few cases however, the only evidence of a performance is a piece of printed ephemera. In these cases the type of piece is identified, eg, brochure. The list is based on imperfect holdings and is updated as gaps in the Library’s holdings for these artists are filled.