"Church With" : a Study of Diaspora Missions in South Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Big Bang? Obstacles to the Emergence of the Rule of Law in Post-Communist Societies

After the Big Bang? Obstacles to the Emergence of the Rule of Law in Post-Communist Societies By KARLA HOFF AND JOSEPH E. STIGLITZ* In recent years economists have increasingly [Such] institutions would follow private been concerned with understanding the creation property rather than the other way around of the “rules of the game”—in the broad sense (pp. 10–11). of political economy—rather than merely the behaviors of agents within a set of rules already But there was no theory to explain how this in place. The transition from plan to market of process of institutional evolution would occur the countries in the former Soviet bloc entailed and, in fact, it has not yet occurred in Russia and an experiment in creating new rules of the many of the other transition economies. A cen- game. In going from a command economy, tral reason for that, according to many scholars, is the weakness of the political demand for the where almost all property is owned by the state, 1 to a market economy, where individuals control rule of law. As Bernard Black et al. (2000) their own property, an entirely new set of insti- observe for Russia, tutions would need to be established in a short period. How could this be done? company managers and kleptocrats op- The strategy adopted in Russia and many posed efforts to strengthen or enforce the capital market laws. They didn’t want a other transition economies was the “Big strong Securities Commission or tighter Bang”—mass privatization of state enterprises rules on self-dealing transactions. -

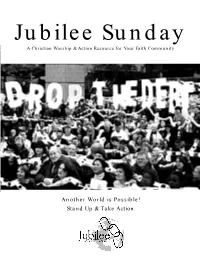

Another World Is Possible! Stand up & Take Action

Jubilee Sunday A Christian Worship & Action Resource for Your Faith Community Another World is Possible! Stand Up & Take Action Contents Letter from Our Executive Director...................................................... 1 Worship Resources.................................................................................... 2 Jubilee Vision....................................................................................... 2 Minute for Mission.............................................................................. 4 Prayers of Intercession for Jubilee Sunday.................................... 6 Hymn Suggestions for Worship........................................................ 7 Jubilee Sunday Sermon Notes........................................................... 9 Children’s Sermon............................................................................... 10 Children and Teen Sunday School Activities................................. 11 Jubilee Action – Another World is Possible....................................... 13 Stand Up Pledge.......................................................................................... 14 Dear partners for a real Jubilee, Thank you for participating in our annual Jubilee Sunday -- your participation in this time will help empower our leaders in the United States to take action for the world’s poorest. Join Jubilee Congregations around the United States on October 14, 2012 to pray for global economic justice, to deepen your community’s understanding of the debt issue, take decisive -

A Read of at the Back of the North Wind

A Read��� of At the Back of the North Wind Col�� Ma�love acDonald’s At the Back of the North Wind (1871) was first serialised inM Good Words for the Young under his own editorship, from October 1868 to November 1870. It was his first attempt at writing a full-length “fairy-story” for children, following on his shorter fairy tales—including “The Selfish Giant,” “The Light Princess,” and “The Golden Key”—written between 1862 and 1867, and published in Dealings with the Fairies (1867). At the Back of the North Wind is, in fact, longer than either of the Princess books that were to follow it, The Princess and the Goblin (1872) and The Princess and Curdie (1882). It tells of the boy Diamond’s life as a cabman’s son in a poor area of mid-Victorian London, and of his meetings and adventures with a lady called North Wind; and it includes a separate fairy tale called “Little Daylight,” two dream-stories, and several poems. Generally well received by the public, it has hardly been out of print since. At the Back of the North Wind is MacDonald’s only fantasy set mainly in this world. In Phantastes (1858), Anodos goes into Fairy Land and in Lilith Mr. Vane finds himself in the Region of the Seven Dimensions. In the Princess books we are in a fairy-tale realm of kings, princesses, and goblins; and the worlds of the shorter fairy tales are all full of fairies, witches, and giants. But Diamond’s story nearly all happens either in Victorian London or in other parts of the world where North Wind takes him. -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

World Population Ageing 2019

World Population Ageing 2019 Highlights ST/ESA/SER.A/430 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division World Population Ageing 2019 Highlights United Nations New York, 2019 The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. The Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs provides the international community with timely and accessible population data and analysis of population trends and development outcomes for all countries and areas of the world. To this end, the Division undertakes regular studies of population size and characteristics and of all three components of population change (fertility, mortality and migration). Founded in 1946, the Population Division provides substantive support on population and development issues to the United Nations General Assembly, the Economic and Social Council and the Commission on Population and Development. It also leads or participates in various interagency coordination mechanisms of the United Nations system. -

Bf File220201204181219.Pdf

True Parents’ Message and News English Version No. 75 天一國 8年 天曆 DECEMBER11 2020 ARTICLE ONE The Importance of the Cheonshimwon By Gi-seong Lee n December 15, 2017, True Mother gave me the heavy responsibility of serving as president of FFWPU for a heavenly Korea. I was so grateful, but on many nights I could not sleep from worries and anxieties. Nevertheless, I had to go toward victory in realizing Vision 2020. I have Obeen running for the past three years as president, holding onto the guidance she gave me, “The more you feel inadequate, the more Heaven will work with you.” Looking back on the past three years, I recall touching memories I had with church members. On February 22, 2018, at the Cheongshim World Peace Center, heavenly Korea had a March Forward Rally for the Inheritance of Heavenly For- tune. That was not a rally at which we listened to True Mother's guidance and made resolutions. The intent of the rally was to enthrone her and to display our firm re- solve. There, I expressed my determination with fear and a trembling heart. I shed tears that day. Twenty thou- sand others did as well. Thus, Heavenly Parent moved in miraculous ways. The foundation to begin emerged, and after Foundation Day, forty families began the heavenly tribal messiah work to bless 430 couples horizontal- ly [in the earthly realm]. In just six months, the forty families multiplied tenfold to over four hundred. I also cherish the Cheonshimwon all-night-prayer vigil. In March 2018, under True Mother's direction, eight leaders did a rotating all-night-prayer vigil there for twenty-one days. -

John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard and Jeffrey D. Sachs

2018 John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard and Jeffrey D. Sachs Table of Contents World Happiness Report 2018 Editors: John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard, and Jeffrey D. Sachs Associate Editors: Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, Haifang Huang and Shun Wang 1 Happiness and Migration: An Overview . 3 John F. Helliwell, Richard Layard and Jeffrey D. Sachs 2 International Migration and World Happiness . 13 John F. Helliwell, Haifang Huang, Shun Wang and Hugh Shiplett 3 Do International Migrants Increase Their Happiness and That of Their Families by Migrating? . 45 Martijn Hendriks, Martijn J. Burger, Julie Ray and Neli Esipova 4 Rural-Urban Migration and Happiness in China . 67 John Knight and Ramani Gunatilaka 5 Happiness and International Migration in Latin America . 89 Carol Graham and Milena Nikolova 6 Happiness in Latin America Has Social Foundations . 115 Mariano Rojas 7 America’s Health Crisis and the Easterlin Paradox . 146 Jeffrey D. Sachs Annex: Migrant Acceptance Index: Do Migrants Have Better Lives in Countries That Accept Them? . 160 Neli Esipova, Julie Ray, John Fleming and Anita Pugliese The World Happiness Report was written by a group of independent experts acting in their personal capacities. Any views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of any organization, agency or programme of the United Nations. 2 Chapter 1 3 Happiness and Migration: An Overview John F. Helliwell, Vancouver School of Economics at the University of British Columbia, and Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Richard Layard, Wellbeing Programme, Centre for Economic Performance, at the London School of Economics and Political Science Jeffrey D. Sachs, Director, SDSN, and Director, Center for Sustainable Development, Columbia University The authors are grateful to the Ernesto Illy Foundation and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research for research support, and to Gallup for data access and assistance. -

Our Common Future

Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future Table of Contents Acronyms and Note on Terminology Chairman's Foreword From One Earth to One World Part I. Common Concerns 1. A Threatened Future I. Symptoms and Causes II. New Approaches to Environment and Development 2. Towards Sustainable Development I. The Concept of Sustainable Development II. Equity and the Common Interest III. Strategic Imperatives IV. Conclusion 3. The Role of the International Economy I. The International Economy, the Environment, and Development II. Decline in the 1980s III. Enabling Sustainable Development IV. A Sustainable World Economy Part II. Common Challenges 4. Population and Human Resources I. The Links with Environment and Development II. The Population Perspective III. A Policy Framework 5. Food Security: Sustaining the Potential I. Achievements II. Signs of Crisis III. The Challenge IV. Strategies for Sustainable Food Security V. Food for the Future 6. Species and Ecosystems: Resources for Development I. The Problem: Character and Extent II. Extinction Patterns and Trends III. Some Causes of Extinction IV. Economic Values at Stake V. New Approach: Anticipate and Prevent VI. International Action for National Species VII. Scope for National Action VIII. The Need for Action 7. Energy: Choices for Environment and Development I. Energy, Economy, and Environment II. Fossil Fuels: The Continuing Dilemma III. Nuclear Energy: Unsolved Problems IV. Wood Fuels: The Vanishing Resource V. Renewable Energy: The Untapped Potential VI. Energy Efficiency: Maintaining the Momentum VII. Energy Conservation Measures VIII. Conclusion 8. Industry: Producing More With Less I. Industrial Growth and its Impact II. Sustainable Industrial Development in a Global Context III. -

The Power of True Love and True Parents' and Heavenly Parent's Teaching Sun Jin Moon January 13, 2018 the Heart to Heart Session

The power of True Love and True Parents' and Heavenly Parent's teaching Sun Jin Moon January 13, 2018 The Heart to Heart Session YAYAM Leadership Retreat, IPEC, Las Vegas During the YAYAM Leadership Retreat Winter 2018 (January 12-14) Sun Jin Nim, accompanied by her husband In Sup Nim, guided young people in a Heart-to-Heart session at IPEC in Las Vegas on January 13, 2018. She read from True Father's autobiography and then lovingly answered questions from the audience. Late in the program she guided them in a meditation for the revival of their spirits, and concluded by giving special gifts to some lucky members of the audience. As with previous occasions, Sun Jin Nim sought to connect very personally with each audience member's heart and to help them understand True Mother's work for the global providence and her love for the members worldwide. Hoon Dok Hae: Leaving Behind a Legacy of Love (p.226 – p.231, As a Peace-Loving Global Citizen) "A true life is a life in which we abandon our private desires and live for the public good. This is a truth taught by all major religious leaders past and present, East and West, whether it be Jesus, Buddha, or the Prophet Mohammed. It is a truth that is so widely known that, sadly, it seems to have been devalued. The passage of time or changes in the world cannot diminish the value of this truth. This is because the essence of human life never changes, even in the midst of rapid change all around the world. -

The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2017

2017 THE STATE OF FOOD SECURITY AND NUTRITION IN THE WORLD BUILDING RESILIENCE FOR PEACE AND FOOD SECURITY REQUIRED CITATION: FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2017. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2017. Building resilience for peace and food security. Rome, FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Programme (WFP) or the World Health Organization (WHO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP or WHO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The designations employed and the presentation of material in the maps do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP or WHO concerning the legal or constitutional status of any country, territory or sea area, or concerning the delimitation of frontiers. All reasonable precautions have been taken by FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. -

Download Bigbang Made Full Album Japanese K2nblog Zinnia Magenta

download bigbang made full album japanese k2nblog Zinnia Magenta. Download Musik, MV/PV Jepang & Korea Full Version + Drama Korea Subtittle Indonesia. Newest Post. Download [Album] BIGBANG - MADE. BIGBANG – MADE [FULL ALBUM] Release Date: 2016.12.13 Genre: Rap / Hip-hop, Ballad, Dance, Folk, Rock Language: Korean Bit Rate: MP3-320kbps + iTunes Plus AAC M4A Big Bang’s tenth anniversary project comes to an end with the last album of the Made series. Besides the Made singles, such as Bang Bang Bang, Loser, Bae Bae and “Let’s Not Fall in Love,” the album also features three new tracks, namely the double title numbers FXXK IT and Last Dance, as well as Girlfriend written by G-Dragon, TOP and YG in-house producer Teddy. Track List: 01. 에라 모르겠다 (FXXK IT) *Title 02. LAST DANCE *Title 03. GIRLFRIEND 04. 우리 사랑하지 말아요 (LET’S NOT FALL IN LOVE) 05. LOSER 06. BAE BAE 07. 뱅뱅뱅 (BANG BANG BANG) 08. 맨정신 (SOBER) 09. IF YOU 10. 쩔어 (ZUTTER) (GD & T.O.P) 11. WE LIKE 2 PARTY. Download Album File: BIGBANG – MADE [Zinnia Magenta].rar Size: 95.9 MB. Download bigbang made full album japanese k2nblog. BIG BANG Albums Download. BIGBANG – Alive (Monster Edition) 1. Still Alive 2. MONSTER 3. FANTASTIC BABY 4. Blue 5. Love Dust 6. FEELING 7. Ain't No Fun 8. BAD BOY 9. EGO 10. Wings 11. Bingle Bingle 12. Haru Haru (Japanese ver.) DOWNLOAD. BIGBANG - Still Alive Special Edition. 1. Still Alive 2. MONSTER 3. Feeling 4. FANTASTIC BABY 5. BAD BOY 6. Blue 7. Round and Round 빙글빙글 (Bingeul Bingeul) 8.