Cultivating Joy & Wonder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Big Bang? Obstacles to the Emergence of the Rule of Law in Post-Communist Societies

After the Big Bang? Obstacles to the Emergence of the Rule of Law in Post-Communist Societies By KARLA HOFF AND JOSEPH E. STIGLITZ* In recent years economists have increasingly [Such] institutions would follow private been concerned with understanding the creation property rather than the other way around of the “rules of the game”—in the broad sense (pp. 10–11). of political economy—rather than merely the behaviors of agents within a set of rules already But there was no theory to explain how this in place. The transition from plan to market of process of institutional evolution would occur the countries in the former Soviet bloc entailed and, in fact, it has not yet occurred in Russia and an experiment in creating new rules of the many of the other transition economies. A cen- game. In going from a command economy, tral reason for that, according to many scholars, is the weakness of the political demand for the where almost all property is owned by the state, 1 to a market economy, where individuals control rule of law. As Bernard Black et al. (2000) their own property, an entirely new set of insti- observe for Russia, tutions would need to be established in a short period. How could this be done? company managers and kleptocrats op- The strategy adopted in Russia and many posed efforts to strengthen or enforce the capital market laws. They didn’t want a other transition economies was the “Big strong Securities Commission or tighter Bang”—mass privatization of state enterprises rules on self-dealing transactions. -

Capper 1998 Phd Karl Barth's Theology Of

Karl Barth’s Theology of Joy John Mark Capper Selwyn College Submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy University of Cambridge April 1998 Karl Barth’s Theology of Joy John Mark Capper, Selwyn College Cambridge, April 1998 Joy is a recurrent theme in the Church Dogmatics of Karl Barth but it is one which is under-explored. In order to ascertain reasons for this lack, the work of six scholars is explored with regard to the theme of joy, employing the useful though limited “motifs” suggested by Hunsinger. That the revelation of God has a trinitarian framework, as demonstrated by Barth in CD I, and that God as Trinity is joyful, helps to explain Barth’s understanding of theology as a “joyful science”. By close attention to Barth’s treatment of the perfections of God (CD II.1), the link which Barth makes with glory and eternity is explored, noting the far-reaching sweep which joy is allowed by contrast with the related theme of beauty. Divine joy is discerned as the response to glory in the inner life of the Trinity, and as such is the quality of God being truly Godself. Joy is seen to be “more than a perfection” and is basic to God’s self-revelation and human response. A dialogue with Jonathan Edwards challenges Barth’s restricted use of beauty in his theology, and highlights the innovation Barth makes by including election in his doctrine of God. In the context of Barth’s anthropology, paying close attention to his treatment of “being in encounter” (CD III.2), there is an examination of the significance of gladness as the response to divine glory in the life of humanity, and as the crowning of full and free humanness. -

About Emotions There Are 8 Primary Emotions. You Are Born with These

About Emotions There are 8 primary emotions. You are born with these emotions wired into your brain. That wiring causes your body to react in certain ways and for you to have certain urges when the emotion arises. Here is a list of primary emotions: Eight Primary Emotions Anger: fury, outrage, wrath, irritability, hostility, resentment and violence. Sadness: grief, sorrow, gloom, melancholy, despair, loneliness, and depression. Fear: anxiety, apprehension, nervousness, dread, fright, and panic. Joy: enjoyment, happiness, relief, bliss, delight, pride, thrill, and ecstasy. Interest: acceptance, friendliness, trust, kindness, affection, love, and devotion. Surprise: shock, astonishment, amazement, astound, and wonder. Disgust: contempt, disdain, scorn, aversion, distaste, and revulsion. Shame: guilt, embarrassment, chagrin, remorse, regret, and contrition. All other emotions are made up by combining these basic 8 emotions. Sometimes we have secondary emotions, an emotional reaction to an emotion. We learn these. Some examples of these are: o Feeling shame when you get angry. o Feeling angry when you have a shame response (e.g., hurt feelings). o Feeling fear when you get angry (maybe you’ve been punished for anger). There are many more. These are NOT wired into our bodies and brains, but are learned from our families, our culture, and others. When you have a secondary emotion, the key is to figure out what the primary emotion, the feeling at the root of your reaction is, so that you can take an action that is most helpful. . -

Finding the Golden Mean: the Overuse, Underuse, and Optimal Use of Character Strengths

Counselling Psychology Quarterly ISSN: 0951-5070 (Print) 1469-3674 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccpq20 Finding the golden mean: the overuse, underuse, and optimal use of character strengths Ryan M. Niemiec To cite this article: Ryan M. Niemiec (2019): Finding the golden mean: the overuse, underuse, and optimal use of character strengths, Counselling Psychology Quarterly, DOI: 10.1080/09515070.2019.1617674 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1617674 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ccpq20 COUNSELLING PSYCHOLOGY QUARTERLY https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1617674 ARTICLE Finding the golden mean: the overuse, underuse, and optimal use of character strengths Ryan M. Niemiec VIA Institute on Character, Cincinnati, OH, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The science of well-being has catalyzed a tremendous amount of Received 28 February 2019 research with no area more robust in application and impact than Accepted 8 May 2019 the science of character strengths. As the empirical links between KEYWORDS character strengths and positive outcomes rapidly grow, the research Character strengths; around strength imbalances and the use of strengths with problems strengths overuse; strengths and conflicts is nascent. The use of character strengths in understand- underuse; optimal use; ing and handling life suffering as well as emerging from it, is particularly second wave positive aligned within second wave positive psychology. Areas of particular psychology; golden mean promise include strengths overuse and strengths underuse, alongside its companion of strengths optimaluse.Thelatterisviewedasthe golden mean of character strengths which refers to the expression of the right combination of strengths, to the right degree, and in the right situation. -

Another World Is Possible! Stand up & Take Action

Jubilee Sunday A Christian Worship & Action Resource for Your Faith Community Another World is Possible! Stand Up & Take Action Contents Letter from Our Executive Director...................................................... 1 Worship Resources.................................................................................... 2 Jubilee Vision....................................................................................... 2 Minute for Mission.............................................................................. 4 Prayers of Intercession for Jubilee Sunday.................................... 6 Hymn Suggestions for Worship........................................................ 7 Jubilee Sunday Sermon Notes........................................................... 9 Children’s Sermon............................................................................... 10 Children and Teen Sunday School Activities................................. 11 Jubilee Action – Another World is Possible....................................... 13 Stand Up Pledge.......................................................................................... 14 Dear partners for a real Jubilee, Thank you for participating in our annual Jubilee Sunday -- your participation in this time will help empower our leaders in the United States to take action for the world’s poorest. Join Jubilee Congregations around the United States on October 14, 2012 to pray for global economic justice, to deepen your community’s understanding of the debt issue, take decisive -

The Art of Cheesemaking

The Art of Cheesemaking What was Little Miss Muffett doing while she sat on her tuffet? She was eating cheese, of course: curds and whey! Ever wonder how natural cheese gets produced? Cheesemaking is a process at once infinitely complex and delightfully simple. Here are the steps. Milk: Quality cheese begins as quality milk. In fact, cheese is why they’re also known as grana-style). To make softer 1 is sometimes referred to as milk’s leap toward immortality. cheeses, such as Mozzarella and Ricotta the curds are cut into Before the cheesemaking process can begin, fluid milk is larger pieces and then very gently maneuvered. tested for purity and quality. Fun fact: It takes nearly 10 pounds of milk to produce just one pound of cheese. Heating & Hooping: Gentle stirring and heating continues until 7 the desired firmness of the curd is achieved. Afterwards, the Standardization: Many commercially-produced cheeses whey is drained, leaving behind just the gelatinous solids. The 2 undergo a heat treatment known as pasteurization that curds are gently molded by being placed into appropriately eliminates the natural microflora of the fluid milk. Part of sized “hoops.” The shape of the hoop reflects the desired final what makes artisan cheese so special is that the cheese is shape of the cheese. often made on the same farm where the animals are milked. This is known as farmstead cheesemaking. Artisan cheese is Pressing: The pressing step helps to determine the final shape also sometimes produced with raw milk, which lends natural 8 and texture of the cheese, as well as to continue to regulate its starter cultures and taste-enhancing microbes. -

Cheese Making Sources: One-Hour Cheese by Claudia Lucero; Edgewood Creamery Website; Science.Howstuffworks.Com;

The Basic Science (It’s Magic!) Behind Cheese Making Sources: One-Hour Cheese by Claudia Lucero; Edgewood Creamery website; Science.HowStuffWorks.Com; Instructional video available on Driftwood Public Library’s new YouTube Channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OY39X-eSLLI&t=144s “Cheesemaking is the controlled process of removing water from milk. This process concentrates the milk’s protein, fat and other nutrients and increases its shelf life. Cheesemaking is one of the earliest examples of biotechnology.” – Edgewood Creamery Like sourdough bread, making cheese is one of the earliest forms of microbiology. The transformation of milk into cheese is one of the most extraordinary of all human discoveries. No one knows exactly when, but it is believed to have happened at about the same time as the domestication of animals such as goats in the fertile crescent region of the Middle East, around 6,000-7,000BC. It is unknown when the first cheese was made, but the legend goes that a nomad was carrying milk in a pouch made of a calf’s stomach lining. Over time (and at the right temperature) the milk fermented. Not wanting to waste the chunky milk, the nomad tried it and liked it. This legend about the first cheese is not unlike that of the first sourdough leavened bread. The components of Cheese: Milk: Made up of water, fats, proteins, bacteria, lactose (a sugar), minerals and more. Unpasteurized milk also contains the enzyme lactase, which helps you digest milk. Salt: Besides adding flavor, “salt is also a great preservative and, under the right conditions, can help turn a previously highly perishable substance (milk) into a stable cheese that doesn’t require regular refrigeration.” Note: When making one-hour cheese, we only use salt for flavor and to control the amount of whey we leave in the curds for texture. -

Lgbts Confront Persecution

Volume 85 - Issue 10 November 16, 2012 LGBTs confront persecution Airband to Campus group offers support to LGBT students take the place BY TYLER LEHMANN of NBDC FEATURES CO-EDITOR BY GILLIAN ANDERSON Recalling dirty looks on campus and A once-popular Northwestern event, harassment in dorms, Northwestern Airband, will be introduced to a new College’s lesbian, gay, bisexual and generation of students. transgender students said they are Airband is a competition in which “persecuted” at the school. In response, groups create a lip-syncing performance NW’s unofficial student-run LGBT to a song or mix of songs. advocacy group has expanded its efforts “It is lip syncing but not the band to raise awareness of perceived LGBT type of lip syncing,” said Aaron discrimination on campus. Beadner, director of student programs. “Everyone should have a place where Most students were still in high they feel safe and free to be who they school when Airband last took place are and not feel judged or persecuted, and on campus four years ago. Some we want to be that for anyone who needs former students who remember it us,” said senior Keely Wright, executive are now working for NW, and a few administrator of LEAP, an organization current students have heard about it for LGBT-affirming students that is from recent graduates. unaffiliated with NW. “I remember Airband as a student,” Taking its name from the acronym said Drew Schmidt who graduated “Love, Education, Acceptance, Pride,” from NW in 2005 and is now the the group clashes with NW’s official audiovisual technician at NW. -

Parenting Teens

Parenting Teens Positive stories about teens rarely make it into the headlines. But, believe it or not, nine in 10 teens do not get into trouble. Do we hear about those in the news?! ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ hether children are toddlers or teens, on more a role of counselor. The warmth, Wpreparing for parenting challenges is affection, and positive communication of a tough! The difficulty with teens is that they counselor, however, must be balanced with are becoming much larger, much more the teen’s need to be independent and in verbal, and are able to fight battles more on charge. One researcher found that teens an adult level. They may experiment with seek information from friends on social risk taking, and the stakes are higher than at events, dating, joining clubs, and other any other developmental stage to this point. social life aspects while they turn to their Teens do not turn into teens overnight. parents for information on education, career There are three phases of adolescence that plans, and money matters. include the teen years: preadolescence (age During late adolescence, there are many 9 to 13), middle adolescence (age 14 to 16) decisions to be made. Teens are beginning and late adolescence (age 17 to 20). to disengage, and they often prepare to During preadolescence, children feel leave home about the same time their disorganized, and their growth is rapid and parents are reflecting on their own lives and uneven. They are not quite adolescents yet needs. At this time, authority with children because their sexual maturity has not fully is redefined and there is a gradual shift completed, and they are often referred to as toward economic and emotional indepen- tweens, meaning between the stages of dence. -

The-Joy-Project.Pdf

“Our eyes of flesh seek joy in the wrong places, define it with a bank- rupt vocabulary, and settle for it using mistaken formulas. Because we don’t know what to do but try harder and hide our shame, we get stuck and sick, depressed and despondent. This dehumanizes us, discourages us, and defeats us. But there is hope! The Joy Project is applied Reformed theology at its best.” –RosaRia champagne ButteRfield, Author, The Gospel Comes with a House Key “Biblically, colorfully, and with realistic precision, Tony Reinke pres- ents God’s work of saving grace as a jamboree of overwhelming sov- ereign joy. This is a book of deep truth that does good to the heart as well as the head.” –J. i. packeR, Professor, Vancouver, British Columbia “The Joy Project is a celebration of Reformed theology, and in this way it’s more in keeping with the Bible’s treatment of the subject—be- hold the beauty before bemoaning the controversies. We cover this topic briefly in our church membership class, and for those who want to pursue it further, this book, for its accessibility and warmth, is the one I’ll recommend first.” –BenJamin VRBicek, Pastor, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania “What do you get when you combine Gretchen Rubin’s The Hap- piness Project with the Five Points of Calvinism and Tony Reinke’s compelling writing? You’re looking at it. It sounds like a weird and unworkable combination, but it works well and results in an out- standingly beautiful presentation of the doctrines of grace. This is the most beautiful presentation of Calvinism I’ve ever read.” –daVid muRRay, Professor, Puritan Reformed Seminary “Tony Reinke’s The Joy Project is a unique and delightful summary of the unfolding drama of God’s sovereign grace. -

Righteous Indignation I

John 2:13-22 13The Jewish Passover was near, so Jesus went up to Jerusalem. 14In the temple courts he found people selling cattle, sheep, and doves, and money changers sitting at tables. 15He made a whip of cords and drove everyone out of the temple courts, along with the sheep and oxen. He scattered the coins of the money changers and overturned their tables. 16To those selling doves he said, “Get these things out of here! Stop turning my Father’s house into a place of business!” 17His disciples remembered that it was written, “Zeal for your house will consume me.” 18So the Jews responded, “What sign are you going to show us to prove you can do these things?” 19Jesus answered them, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up again.” 20The Jews said, “It took forty-six years to build this temple! And you are going to raise it in three days?” 21But Jesus was speaking about the temple of his body. 22When Jesus was raised from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this. Then they believed the Scripture and what Jesus had said. Righteous Indignation I. You sigh as you enter church. It’s that time of year again—the time leading up to Passover. Jewish faithful from all over the world are coming to make their pilgrimage to the temple to make their sacrifices and pay their temple-tax. It probably all seems very practical and pragmatic to the Jewish out-of-town-ers. They’ll stop in the equivalent of the narthex area for all the necessary items for their sacrifices. -

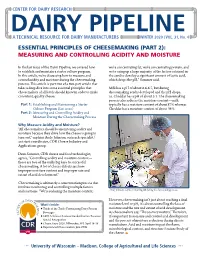

Measuring and Controlling Acidity and Moisture

CENTER FOR DAIRY RESEARCH DAIRY PIPELINE A TECHNICAL RESOURCE FOR DAIRY MANUFACTURERS WINTER 2020 | VOL. 31, No. 4 ESSENTIAL PRINCIPLES OF CHEESEMAKING (PART 2): MEASURING AND CONTROLLING ACIDITY AND MOISTURE In the last issue of the Dairy Pipeline, we covered how we’re concentrating fat, we’re concentrating protein, and to establish and maintain a starter culture program. we’re using up a large majority of the lactose retained in In this article, we’re discussing how to measure and the curd to develop a significant amount of lactic acid, control acidity and moisture during the cheesemaking which drops the pH,” Sommer said. process. This article is part two of a two-part article that takes a deep dive into some essential principles that Milk has a pH of about 6.6-6.7, but during cheesemakers of all levels should know in order to make cheesemaking acid is developed and the pH drops, consistent, quality cheese. i.e. Cheddar has a pH of about 5.1. The cheesemaking process also reduces the moisture content—milk Part 1: Establishing and Maintaining a Starter typically has a moisture content of about 87% whereas Culture Program (last issue) Cheddar has a moisture content of about 38%. Part 2: Measuring and Controlling Acidity and Moisture During the Cheesemaking Process Why Measure Acidity and Moisture? “All cheesemakers should be monitoring acidity and moisture because they drive how the cheese is going to turn out,” explains Andy Johnson, outreach specialist/ assistant coordinator, CDR Cheese Industry and Applications group. Dean Sommer, CDR cheese and food technologist, agrees, “Controlling acidity and moisture content— those are two of the really big keys to successful cheesemaking.