Yekum Purkan”: Intended to Be Highly Familiar, Yet Expressed in a Language That Today Is Anything But

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

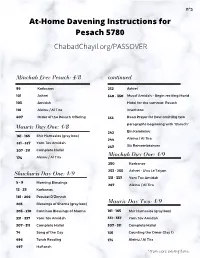

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Young Israel Congregation Shmooze News

Young Israel Congregation Shmooze News 9580 Abbott Avenue, Surfside, FL 33154 www.yicbh.org - [email protected] Parshas Vayikra, March 28, 2020 Rabbi Moshe Gruenstein – [email protected] President Menno Ratzker . PLEASE STAY SAFE AND TAKE CARE OF YOURSELVES. SHABBAT SHALOM! Shabbos Dear Members and Friends, Candle Lighting 7:17PM As we now begin our third Shabbos in solitary confinement, may the Almighty have mercy on his cherished nation and bring an end to this nightmare which has so afflicted the entire world. We are living in a time that is so surreal that every morning when we Shabbos Afternoon wake up, we have to pinch ourselves to be reminded that this is Mincha By 7:20PM actually happening. May we see an end to this very soon. Havdalah 8:21PM : As we begin yet another full Shabbos at home, let's again talk about that sacred topic called "home," for we obviously see that is where G-d wants us to spend all our time. We know that one of the major mitzvos of Pesach is the eating of the korban Pesach (pascal lamb) - the first family mitzvah. This was the mitzvah that G-d wanted us to fulfill right before the redemption. He wanted us to go into our homes with our families, close the door, Weekday Mincha place blood on the inside of the doorpost, and eat the Korban Sun-Thu By 7:20PM Pesach; while outside the home was absolute pandemonium - death, destruction, and dark forces wreaking havoc. What exactly Next Fri candle lighting 7:20PM is the message of this mitzvah on the eve of the Geula AM(redemption)? I believe the message is as follows. -

Wednesday Night Rebbe’S Haggadah) Vol

Thursday, 15 Nissan, 5780 - For local candle Your complete guide to this Tuesday, lighting times visit week's halachos and minhagim. 20 Nissan, 5780 Chabad.org/Candles Unfortunately, due to the coronavirus, this The Seder Pesach minyanim are not taking place. • Begin the Seder as soon as possible, so the However, we still felt it appropriate to include children will not fall asleep.3 the halachos associated with tefillah betzibur, • The Rebbe Rashab once told the Frierdiker Rebbe: etc., in this issue of the Luach. “During the Seder, and especially when the door is opened, we must Erev Yom Tov reminder: think about being a “The Haggadah Don’t forget to make an eiruv tavshilin! mentch, and Hashem should be said loudly, with great joy and will help. Don’t ask much kavanah.” for gashmiyus; ask (Siddur HaArizal, for ruchniyus.” (The cited in Likkutei Sichos Wednesday night Rebbe’s Haggadah) vol. 22, p. 179 fn. 40) 15 Nissan, 5780 | First night of Pesach Preparing the Kaarah Things to do • The kaarah is assembled at night, before beginning the Seder.4 1 • After Minchah but before shekiah, recite the • If possible, choose concave (bowl-shaped) Seder Korban Pesach. matzos for the Seder plate.5 • Before Yom Tov, light a long-burning candle, from • To avoid any similarity to the korban pesach, the which the candles can be lit tomorrow night. Frierdiker Rebbe would remove almost6 all the • Ideally, women and girls should light candles meat from the zeroa bone (although it was from 2 before shekiah. When bentching licht, the a chicken, which is invalid for a korban to begin berachos of Lehadlik Ner Shel Yom Tov and with).7 Shehecheyanu are said. -

Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה Prayers for Pesach for Tehillat Hashem Siddur, Annotated Edition while in quarantine Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 101 Ashrei 232 Ashrei 103 Amidah 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting 116 Aleinu Morid Hatol for the summer 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 242 Ein Kelokeinu 244 Aleinu Maariv Day One: 4/8 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) Minchah Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 331 - 337 Amidah 174 Aleinu 267 Aleinu Shacharis Day One: 4/9 Maariv Day Two: 4/9 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 12 - 25 Korbanos 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 174 Aleinu 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 496 Torah Reading 497 Haftorah 1 Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - Include gray 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah box p214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of the Day paragraphs 498 Torah Reading 218 Song of the Day 501 Haftorah 506 Torah Reading 232 Ashrei 508 Haftorah 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah 230 Yekum Purkan, first one only 242 Ein Kelokeinu 232 Ashrei 244 Aleinu -

Tz7-Sample-Corona II.Indd

the lax family special edition Halachic Perspectives on the Coronavirus II נקודת מבט על נגיף הקורונה ב׳ Tzurba M’Rabanan First English Edition, 2020 Volume 7 Excerpt – Coronavirus II Mizrachi Press 54 King George Street, PO Box 7720, Jerusalem 9107602, Israel www.mizrachi.org © 2020 All rights reserved Written and compiled by Rav Benzion Algazi Translation by Rav Eli Ozarowski, Rav Yonatan Kohn and Rav Doron Podlashuk (Director, Manhigut Toranit) Essays by the Selwyn and Ros Smith & Family – Manhigut Toranit participants and graduates: Rav Otniel Fendel, Rav Jonathan Gilbert, Rav Avichai Goodman, Rav Joel Kenigsberg, Rav Sam Millunchick, Rav Doron Podlashuk, Rav Bentzion Shor General Editor and Author of ‘Additions of the English Editors’: Rav Eli Ozarowski Board of Trustees, Tzurba M’Rabanan English Series: Jeff Kupferberg (Chairman), Rav Benzion Algazi, Rav Doron Perez, Rav Doron Podlashuk, Ilan Chasen, Adam Goodvach, Darren Platzky Creative Director: Jonny Lipczer Design and Typesetting: Daniel Safran With thanks to Sefaria for some of the English translations, including those from the William Davidson digital edition of the Koren Noé Talmud, with commentary by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz www.tzurba.com www.tzurbaolami.com Halachic Perspectives on the Coronavirus II נקודת מבט על נגיף הקורונה ב׳ Introduction “Porch” and Outdoor Minyanim During Coronavirus Restrictions Responding to a Minyan Seen or Heard Online Making a Minyan Using Online Platforms Differences in the Tefilla When Davening Alone Other Halachot Related to Tefilla At Home dedicated in loving memory of our dear sons and brothers יונתן טוביה ז״ל Jonathan Theodore Lax z”l איתן אליעזר ז״ל Ethan James Lax z”l תנצב״ה marsha and michael lax amanda and akiva blumenthal rebecca and rami laifer 5 · נקודות מבט הלכתיות על נגיף הקורונה ב׳ צורבא מרבנן Introduction In the first shiur concerning the coronavirus, we discussed some of the halachic sources relating to the proper responses, both physical and spiritual, to an epidemic or pandemic. -

Mussaf Yekum Purkan → End of Full Kaddish (Or Through the End of Adon Olam If You Are Asked to Lead the Final Prayers Following Full Kaddish)

Mussaf Yekum Purkan → End of Full Kaddish (or through the end of Adon Olam if you are asked to lead the final prayers following Full Kaddish). At the end of the Brachot following the Haftarah, move towards the Shulhan (table) and stand next to the reader of the Haftarah. After the final Brachah, wait for the Gabbai to announce the pages and then chant out loud the four words “Yekum Purkan min sh’maya” (412 in Sim Shalom, 448 in Artscroll). You may stand “at ease.” Read silently for the next THREE paragraphs; pick up again out loud at the words “V’chol Mi She’oskim…” towards the end of the third paragraph. At the end of that paragraph, the Gabbai will lead the congregation in the prayers for Israel and America. On the Shabbat preceding Rosh Chodesh, there is a blessing over the new moon. Following are instructions for that (tunes can be found at end of Side B): 1. After Prayers for States, Cong reads "Y'hi Ratzon" quietly, 2. Chazzan reads Yhi Ratzon out loud 3. Gabbai announces “Molad” – day and time of the new moon’s appearance 4. [In some Congs, Cong now reads Mi She'asah silently. In some, they skip it and only Chazzan says it out loud. Pause to allow them to say it; if they are not saying it, continue below…] 5. Chazzan Takes Torah, says "Mi She'asah Nisim" out loud followed by "Rosh Chodesh (name of month) yehiyeh b’yom (day of the week) haba alenu l’tovah" Cong then repeats "Rosh Chodesh (blank) yehiyeh..." and continues with Paragraph "Yichadshehu" 6. -

Shabbat Prayer Book Guide

ב"ה SHABBAT PRAYER BOOK GUIDE IN THE HEART OF MERCER ISLAND, WASHINGTON Copyright © 2016 by Island Synagogue Kehillat Shevet Achim ISBN: 978-1-59849-214-9 Printed in the United States of America The material in this booklet is considered holy because of the Torah explanations it contains and cannot be thrown out or destroyed improperly. Island Synagogue Kehillat Shevet Achim 8685 SE 47th Street Mercer Island, Washington 98040 206-275-1539 www.islandsynagogue.org All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, in part, in any form, without the permission of the author. Requests for such permissions should be addressed to: Classic Day Publishing 943 NE Boat Street Seattle, Washington 98105 206-860-4900 www.classicdaypub.com THIS PUBLICATION HAS BEEN MADE POSSIBLE BY THE GENEROUS SUPPORT OF NATASHA & ELI SRULOWITZ INSCRIPTION ON THE ARON KODESH V’ASUE LEE MIKDASH V’SHACHANTEE B’TOCHAM. THEY SHALL MAKE FOR ME A SANCTUARY AND I WILL DWELL IN THEIR MIDST. THE PAROCHET The parochet (curtain) was designed by Jeanette Kuvin Oren. The blue design in the lower half of the parochet represents the parting of the Sea of Reeds as the Israelites left Egypt. G-d led the Israelites through the wilderness with a column of smoke and fire, represented by the yellows and reds in the form of the He- brew letter “shin” – a symbol for G-d’s name. The design is or- ganized in a grid of five columns, representing the five books of the Torah, and ten rows for the Ten Commandments. -

Sukkot & Shmini Atzeret 5781

FROM THE DESK OF RABBI BRAHM WEINBERG SUKKOT & SHMINI ATZERET 5781 HALACHOT, MINHAGIM, DAVENING INSTRUCTIONS FOR THOSE COMING TO SHUL OR DAVENING AT HOME Details of what to do when davening without a minyan are shaded in grey ARBA MINIM ● It is proper to try to assemble your Arba Minim sets before Shabbat/Yom Tov (to avoid any issues of tying and to avoid tearing the leaves off when you place them in the holders). If you are wrapping them in wet towels you must do that before Shabbat/Yom Tov as well (to avoid issues of squeezing/soaking and watering the leaves). ● On Shabbat the Arba Minim are muktzah. ● On Yom Tov you may remove the Arba Minim from the wet towel and may return them to that same towel that had been wet before Yom Tov. If that same towel is getting dry and you wish to add more water to it on Yom Tov, you can do so indirectly by wetting your hands and then shaking off the water into that towel that is around the Arba Minim. ● Instructions for shaking lulav (applies throughout Sukkot): ○ Arba Minim should be taken before the recitation of Hallel ○ Before reciting the beracha/ot, the etrog is held upside down (with the pitom facing down) in the left hand. The lulav, hadasim and aravot are held in the right hand (for lefty’s inverse). The beracha (or berachot on the first day) is recited and then the etrog is turned to the upright position with the pitom facing upwards. One then shakes the lulav in all directions. -

Joseph Kushner Hebrew Academy Middle School Haggadah

JOSEPH KUSHNER HEBREW ACADEMY 5779 MIDDLE SCHOOL PESACH HAGGADAH 2019 Joseph Kushner Hebrew Academy 110 South Orange Ave Livingston, NJ 07038 (862) 437-8000 www.jkha.org תשע"ט The 2019- Joseph Kushner Hebrew Academy Middle School Haggadah הגדה של פסח Editor Rabbi Yaacov Feit Cover Design Ayala East Tzofiya Pittinsky Contributors JKHA Middle School Faculty and Students Dedicated by Sherry and Henry Stein in memory of their parents: Arie & Eva Halpern Dr. Morris & Shifra Epstein Bernard Stein 1 2 It is the night that we have all been waiting for. The preparation for the night of the Seder has no parallel in the Jewish calendar. Weeks of tireless effort and seemingly endless expenditures culminate in this anticipated night. We bake matzah, clean our houses, purchase or kasher new dishes, prepare our kitchens, cook, search for chametz and burn the chametz. Halacha even ensures that we prepare for the recitation of the Haggadah itself. The Rama (Orach Chaim 430) writes that during the time of mincha on Shabbat Hagadol, one should recite the main part of Maggid. We come to the Seder night more than ready to fulfill our obligation to pass on the story of Yetziat Mitzrayim together with its fundamentals of emunah to our children. And yet, each year I find myself handicapped. The hour is late and the children are tired. Engaging various types of children with different learning styles and personalities with ages ranging from pre-school through high school seems like a daunting task. Not to mention all the distractions. And sometimes I feel that the celebrated Haggadah itself presents to us one of the biggest challenges. -

Rosh Hashana Service Outlines, 5781

ADATH Judaism for the next generation 27 Ellul, 5780 – September 16, 2020 Rosh Hashana Service Outlines, 5781 This is what we are preparing for services at ADATH this year, including pages numbers in the Artscroll and Birnbaum Rosh Hashana Machzor. Everything here is tentative, as of today, and is subject to refinement and change. Please share your feedback and questions with Rabbi Whitman, [email protected]. If you are praying at home, without a Minyan, follow these outlines for the 2-hour service, and omit those portions requiring a Minyan (Kaddish, Bor’chu, Reader’s Repetition) but include Kel Orech Din, Yimloch Hashem L’Olam, and Unesaneh Tokef as indicated below. Instead of Torah Reading, read/study the Torah portion, Maftir, and Haftorah from your Machzor or Chumash. If you are praying at home, without a Minyan, there is no difference for you between the Indoor outline and the Outdoor outline. For Shofar on Sunday, second day Rosh Hashana, you may also choose to join us outside on Harrow Crescent in front of ADATH for Shofar only, while the street is closed for us by Hampstead Security – there is plenty of space for 2m distancing - at 10 a.m., 12 p.m., 2 p.m., or 5 p.m. Or we will come to you. Just let Rabbi Whitman know ([email protected]), and we will arrange one of us to come to you in the afternoon. Michael Whitman, RABBI ADATH ISRAEL POALE ZEDEK ANSHEI OZEROFF [email protected] www.adath.ca t: 514-482-4252 f: 514-482-6216 223 Harrow Crescent, Hampstead Quebec H3X 3X7 CANADA ADATH Judaism for the next generation 2-Hour Service, Indoors - First Day, Shabbat Artscroll Birnbaum Brachos 184 59 Shir Shel Yom 178 99 L’David Hashem Ori 178 45 Mourner’s Kaddish 220 45 Baruch SheOmar 222 135 Ashrei 244 153 Nishmas 258 165 Half Kaddish 264 171 Bor’chu 266 171 From Bor’chu till Amidah, omit everything not said on a regular Shabbat morning. -

4 Page Guide to SHABBAT Davening at Home

בס״ד Guide to SHABBAT Davening at Home Compiled By Rabbi Phil Kaplan בס״ד All page numbers refer to the green “Authorised Daily Prayer Book” (used at The Great Synagogue.) SHABBAT MORNING PESUKEI D’ZIMRA Tefillah Notes Page Number Blessings upon waking Blessing on handwashing and Bottom of 12 - 16 blessings on the Torah Birchot HaShachar, Blessings recounting all the gifts Bottom of 16 - 24 Morning Blessings God gives us each and every day. Korbanot - Rebbe Yishmael Excerpts from the Torah and Bottom of 24 - 32 Mishnah dealing with the sacrificial offerings. This ends with an excerpt from the Talmud, Rabbi Yishmael’s interpretive principles. With a minyan, this would normally be followed by Kaddish d’Rabbanan. Without a minyan, do not say Kaddish. Shir shel Yom Psalm for the Sabbath day. Bottom of 152 Mizmor Shir Chanukat A Psalm of David. 322 HaBayit Baruch She'amar - end of All texts in this section can be said 326- middle of 366 Pesukei d’Zimra independently without a minyan בס״ד All page numbers refer to the green “Authorised Daily Prayer Book” (used at The Great Synagogue.) SHABBAT MORNING SHACHARIT Tefillah Notes Page Number Shochen Ad - Barchu Say the words of Shochen Ad, Bottom of 366 - 368 UvMakhalot, Yishtabach. Skip half kaddish and Barchu, when davening without a minyan. Blessings preceding Shema Includes Yotzer Or and Ahavah Bottom of 370 - 380 Raba. El Adon on page 374 is traditionally sung. Shema When praying without a minyan, 382 - 384 say the three words at the very top of the page, “El Melech Ne’eman,” and then proceed with Shema as usual. -

Sukkot at Home Tefilla Guide Compiled by Abe Rosenberg (Page Numbers from the Complete Artscroll Siddur)

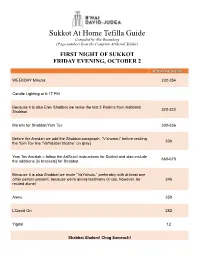

Sukkot At Home Tefilla Guide Compiled by Abe Rosenberg (Page numbers from the Complete ArtScroll Siddur) FIRST NIGHT OF SUKKOT FRIDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 2 ArtScroll Siddur WEEKDAY Mincha 232-254 Candle Lighting at 6:17 PM Because it is also Erev Shabbat we recite the last 2 Psalms from Kabbalat 320-322 Shabbat. Ma’ariv for Shabbat/Yom Tov 330-336 Before the Amidah we add the Shabbat paragraph, “V’shomru” before reciting 336 the Yom Tov line “VaYidaber Moshe” (in gray) Yom Tov Amidah – follow the ArtScroll instructions for Sukkot and also include 660-670 the additions [in brackets] for Shabbat Because it is also Shabbat we recite “VaYichulu,” preferably with at least one other person present, because we’re giving testimony (it can, however, be 346 recited alone) Alenu 350 L’David Ori 282 Yigdal 12 Shabbat Shalom! Chag Sameach! FIRST DAY OF SUKKOT SATURDAY MORNING, OCTOBER 3 ArtScroll Siddur 12-52; P’sukei D’Zimrah 368-404 Shacharit for Shabbat/Yom Tov – Follow the ArtScroll instructions: We recite 406-420 the Shabbat paragraphs beginning with HaKol Yoducha Yom Tov Amidah – follow the ArtScroll instructions for Sukkot and also include 660-670 the additions [in brackets] for Shabbat We recite the full Hallel (we do NOT take the Lulav and Etrog on Shabbat) 632-642 Song of the Day for Shabbat followed by L’David Ori (We do not recite Anim 488 Zemirot) When davening at home we do not recite the tefillot associated with the Torah Reading. This is however a good time to look through the verses in Vayikra (22:26- 23:44) normally read in shul on