Joseph Kushner Hebrew Academy Middle School Haggadah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Follow a Hevrat Pinto Publication Pikudei 381

The Path To Follow A Hevrat Pinto Publication Pikudei 381 Under the Direction of Rabbi David H. Pinto Shlita Adar I 29th 5771 www.hevratpinto.org | [email protected] th Editor-in-Chief: Hanania Soussan March 5 2011 32 rue du Plateau 75019 Paris, France • Tel: +331 48 03 53 89 • Fax: +331 42 06 00 33 Rabbi David Pinto Shlita Batei Midrashim As A Refuge Against The Evil Inclination is written, “These are the accounts of the Sanctuary, the Sanctuary of Moreover, what a person studies will only stay with him if he studies in a Beit Testimony” (Shemot 38:21). Our Sages explain that the Sanctuary was HaMidrash, as it is written: “A covenant has been sealed concerning what we a testimony for Israel that Hashem had forgiven them for the sin of the learn in the Beit HaMidrash, such that it will not be quickly forgotten” (Yerushalmi, golden calf. Moreover, the Midrash (Tanchuma, Pekudei 2) explains Berachot 5:1). I have often seen men enter a place of study without the intention that until the sin of the golden calf, G-d dwelled among the Children of of learning, but simply to look at what was happening there. Yet they eventually ItIsrael. After the sin, however, His anger prevented Him from dwelling among them. take a book in hand and sit down among the students. This can only be due to the The nations would then say that He was no longer returning to His people, and sound of the Torah and its power, a sound that emerges from Batei Midrashim and therefore to show the nations that this would not be the case, He told the Children conquers their evil inclination, lighting a spark in the heart of man so he begins to of Israel: “Let them make Me a Sanctuary, that I may dwell among them” (Shemot study. -

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

A Taste of Torah

Parshas Teruma February 19, 2021 A Taste of Torah Stories for the Soul Hungry for War by Rabbi Yosef Melamed Take to Give Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin (1749-1821), As Purim approaches and the excitement over the fourteenth of Adar. Taanis Esther thus the founder and head of the Volozhin this special holiday grows, this week’s parsha commemorates the fast of the day of battle Yeshiva, once travelled to Minsk to raise against the enemies of the Jewish People. is supplemented with Parshas Zachor, the desperately-needed funds to keep the second of the four special supplement parshios Having established the origins of the fast, we yeshiva afloat. In Minsk lived two men, Reb of this time of the year. Parshas Zachor features must now explore why fasting is important Baruch Zeldowitz and Reb Dober Pines, the Torah commandment to remember the while fighting a war, specifically a war against who served as gabbaim (representatives) to evil that the nation of Amalek perpetrated Amalek. collect money for the yeshiva. Rav Chaim against the fledgling Jewish Nation. Rabbi Gedalya Schorr (1910-1979) offers the visited Rabbi Zeldowitz and informed him The commentators explain that reading this following enlightening explanation: The evil of of the dire financial straits in which the parsha is an appropriate forerunner to Purim Amalek and its power stems from the ideology yeshiva found itself, specifying the large because Haman, the antagonist of the Purim that the world is run randomly through sum of money that was needed to stabilize story, was a direct descendent of Amalek who nature and is not subject to any Divine plan the situation. -

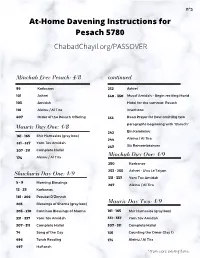

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Young Israel Congregation Shmooze News

Young Israel Congregation Shmooze News 9580 Abbott Avenue, Surfside, FL 33154 www.yicbh.org - [email protected] Parshas Vayikra, March 28, 2020 Rabbi Moshe Gruenstein – [email protected] President Menno Ratzker . PLEASE STAY SAFE AND TAKE CARE OF YOURSELVES. SHABBAT SHALOM! Shabbos Dear Members and Friends, Candle Lighting 7:17PM As we now begin our third Shabbos in solitary confinement, may the Almighty have mercy on his cherished nation and bring an end to this nightmare which has so afflicted the entire world. We are living in a time that is so surreal that every morning when we Shabbos Afternoon wake up, we have to pinch ourselves to be reminded that this is Mincha By 7:20PM actually happening. May we see an end to this very soon. Havdalah 8:21PM : As we begin yet another full Shabbos at home, let's again talk about that sacred topic called "home," for we obviously see that is where G-d wants us to spend all our time. We know that one of the major mitzvos of Pesach is the eating of the korban Pesach (pascal lamb) - the first family mitzvah. This was the mitzvah that G-d wanted us to fulfill right before the redemption. He wanted us to go into our homes with our families, close the door, Weekday Mincha place blood on the inside of the doorpost, and eat the Korban Sun-Thu By 7:20PM Pesach; while outside the home was absolute pandemonium - death, destruction, and dark forces wreaking havoc. What exactly Next Fri candle lighting 7:20PM is the message of this mitzvah on the eve of the Geula AM(redemption)? I believe the message is as follows. -

Identity, Spectacle and Representation: Israeli Entries at the Eurovision

Identity, spectacle and representation: Israeli entries at the Eurovision Song Contest1 Identidad, espectáculo y representación: las candidaturas de Israel en el Festival de la Canción de Eurovisión José Luis Panea holds a Degree in Fine Arts (University of Salamanca, 2013), and has interchange stays at Univer- sity of Lisbon and University of Barcelona. Master’s degree in Art and Visual Practices Research at University of Castilla-La Mancha with End of Studies Special Prize (2014) and Pre-PhD contract in the research project ARES (www.aresvisuals.net). Editor of the volume Secuencias de la experiencia, estadios de lo visible. Aproximaciones al videoarte español 2017) with Ana Martínez-Collado. Aesthetic of Modernity teacher and writer in several re- views especially about his research line ‘Identity politics at the Eurovision Song Contest’. Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, España. [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-8989-9547 Recibido: 01/08/2018 - Aceptado: 14/11/2018 Received: 01/08/2018 - Accepted: 14/11/2018 Abstract: Resumen: Through a sophisticated investment, both capital and symbolic, A partir de una sofisticada inversión, capital y simbólica, el Festival the Eurovision Song Contest generates annually a unique audio- de Eurovisión genera anualmente un espectáculo audiovisual en la ISSN: 1696-019X / e-ISSN: 2386-3978 visual spectacle, debating concepts as well as community, televisión pública problematizando conceptos como “comunidad”, Europeanness or cultural identity. Following the recent researches “Europeidad” e “identidad cultural”. Siguiendo las investigaciones re- from the An-glo-Saxon ambit, we will research different editions of cientes en el ámbito anglosajón, recorreremos sus distintas ediciones the show. -

Holiness-A Human Endeavor

Isaac Selter Holiness: A Human Endeavor “The Lord spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the whole Israelite community and say to them: You shall be holy, for I, the Lord your God, am holy1.” Such a verse is subject to different interpretations. On the one hand, God is holy, and through His election of the People of Israel and their acceptance of the yoke of heaven at Mount Sinai, the nation attains holiness as well. As Menachem Kellner puts it, “the imposition of the commandments has made Israel intrinsically holy2.” Israel attains holiness because God is holy. On the other hand, the verse could be seen as introducing a challenge to the nation to achieve such a holiness. The verse is not ascribing an objective metaphysical quality inherent in the nation of Israel. Which of these options is real holiness? The notion that sanctity is an objective metaphysical quality inherent in an item or an act is one championed by many Rishonim, specifically with regard to to the sanctity of the Land of Israel. God promises the Children of Israel that sexual morality will cause the nation to be exiled from its land. Nachmanides explains that the Land of Israel is more sensitive than other lands with regard to sins due to its inherent, metaphysical qualities. He states, “The Honorable God created everything and placed the power over the ones below in the ones above and placed over each and every people in their lands according to their nations a star and a specific constellation . but upon the land of Israel - the center of the [world's] habitation, the inheritance of God [that is] unique to His name - He did not place a captain, officer or ruler from the angels, in His giving it as an 1 Leviticus 19:1-2 2 Maimonidies' Confrontation with Mysticism, Menachem Kellner, pg 90 inheritance to his nation that unifies His name - the seed of His beloved one3”. -

The Philosophy of Modern Orthodox Judaism - 14785

Syllabus The Philosophy of Modern Orthodox Judaism - 14785 Last update 03-02-2021 HU Credits: 2 Degree/Cycle: 2nd degree (Master) Responsible Department: Jewish Thought Academic year: 0 Semester: 2nd Semester Teaching Languages: English Campus: Mt. Scopus Course/Module Coordinator: Prof. Arnold Ira Davidson Coordinator Email: [email protected] Coordinator Office Hours: Teaching Staff: Prof Arnold Ira Davidson page 1 / 4 Course/Module description: The Philosophy of Modern Orthodox Judaism: Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik The thought of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik is the philosophical foundation of Modern Orthodox Judaism. In this course, we will examine R. Soloveitchik's conception of halakhic method, his elaboration of the notion of masorah, and his idea of halakhic morality. Although we will study a number of texts from different periods of R. Soloveitchik's thought, our main text will be his collection of essays "Halakhic Morality. Essays on Ethics and Masorah". Readings from R. Soloveitchik will be supplemented by some essays of Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein and others. The course will aim to provide a philosophical and theological characterization of Modern Orthodox Judaism, and we will draw some contrasts with both Haredi and Reform Judaism. Course/Module aims: To study the philosophical foundations of Modern Orthodox Judaism Learning outcomes - On successful completion of this module, students should be able to: To provide an understanding of the ideals of Modern Orthodox Judaism, especially as articulated by Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik Attendance requirements(%): 100% Teaching arrangement and method of instruction: Close reading and discussion of the texts Course/Module Content: see description above Required Reading: Week 1 Orthodox Judaism and Philosophy: Bifurcation or Integration: David Shatz, The Overexamined Life is not Worth Living, in Jewish Thought in Dialogue. -

Wednesday Night Rebbe’S Haggadah) Vol

Thursday, 15 Nissan, 5780 - For local candle Your complete guide to this Tuesday, lighting times visit week's halachos and minhagim. 20 Nissan, 5780 Chabad.org/Candles Unfortunately, due to the coronavirus, this The Seder Pesach minyanim are not taking place. • Begin the Seder as soon as possible, so the However, we still felt it appropriate to include children will not fall asleep.3 the halachos associated with tefillah betzibur, • The Rebbe Rashab once told the Frierdiker Rebbe: etc., in this issue of the Luach. “During the Seder, and especially when the door is opened, we must Erev Yom Tov reminder: think about being a “The Haggadah Don’t forget to make an eiruv tavshilin! mentch, and Hashem should be said loudly, with great joy and will help. Don’t ask much kavanah.” for gashmiyus; ask (Siddur HaArizal, for ruchniyus.” (The cited in Likkutei Sichos Wednesday night Rebbe’s Haggadah) vol. 22, p. 179 fn. 40) 15 Nissan, 5780 | First night of Pesach Preparing the Kaarah Things to do • The kaarah is assembled at night, before beginning the Seder.4 1 • After Minchah but before shekiah, recite the • If possible, choose concave (bowl-shaped) Seder Korban Pesach. matzos for the Seder plate.5 • Before Yom Tov, light a long-burning candle, from • To avoid any similarity to the korban pesach, the which the candles can be lit tomorrow night. Frierdiker Rebbe would remove almost6 all the • Ideally, women and girls should light candles meat from the zeroa bone (although it was from 2 before shekiah. When bentching licht, the a chicken, which is invalid for a korban to begin berachos of Lehadlik Ner Shel Yom Tov and with).7 Shehecheyanu are said. -

Guarantors the Judaism Site

Torah.org Guarantors The Judaism Site https://torah.org/torah-portion/hamaayan-5772-vayigash/ GUARANTORS by Shlomo Katz Parshas Vayigash Guarantors Volume 26, No. 11 Sponsored by Milton Cahn in memory of his mother Abby Cahn (Bracha bat Moshe a"h) and his wife Felice Cahn (Faygah Sarah bat Naftoli Zev a"h) King Shlomo writes in Mishlei (6:1-3), "My child, if you have been a guarantor for your friend, if you have given your handshake to a stranger, you have been trapped by the words of your mouth, snared by the words of your mouth--do this, therefore, my child, and be rescued, for you have come into your fellow's hand: Go humble yourself [before him] and let your fellow be your superior." R' Yehoshua ibn Shuiv (Spain; early 14th century) writes that these verses, like much of the book of Mishlei, can be interpreted on multiple levels. On the simplest level, these verses teach that a person should be careful with his words in order that he not get himself into unpleasant situations. If he has gotten himself into a difficult predicament, he should do his best to extricate himself. Being a guarantor is an example of a situation to be avoided, writes R' ibn Shuiv. He continues: Yaakov's son, Yehuda, was not careful with his words and became a guarantor for his brother Binyamin. Thus we read at the beginning of our parashah how Yehuda tried to extricate himself from his predicament. As King Shlomo suggests, Yehuda humbled himself before the Egyptian viceroy, who, unbeknownst to Yehuda, was Yosef. -

Don't Ask, Don't Tell at Y.U

The Jewish Star Independent and original reporting from the Orthodox communities of Long Island VOL. 8, NO. 53 JANUARY 1, 2010 | 15 TEVET 5770 www.thejewishstar.com THE STORY BEHIND HESDER A HANDLE ON THE SCANDAL HE MAY BE PIUS... Rabbi Chaim Goldvicht and Kerem B’Yavneh The fallout from Tropper’s fall But is he a saint? Page 4 Page 5 Page 13 I N M Y V I E W Compassion Don’t ask, is also a don’t tell at Y.U. B Y M I C H A E L O R B A C H pain and the conflict that is caused by someone being gay in the Orthodox Jewish As willing as the four panelists on world.” the dais were to speak about their sex- The gathering was far from a gay ual orientation, it seemed clear they pride event but instead a sober value would have rather been in the audi- acknowledgment. In a twist on the ence. gay-pride slogan of the 1970s, it said: “I'm gay, and nothing I've done We're here, we're queer, and we're can change that,” said Avi Kopstick, sorry about it. the president of Yeshiva University's “The halacha, as expressed explic- B Y R A B B I H E R S C H E L B I L L E T Tolerance Club and an openly gay stu- itly in the Torah and in the dent at the college. “I fought for six Chachamim, is clear to everyone here, s an Orthodox Jew and an years, every Rosh Hashana, denying and this is not what we're here to dis- ordained rabbi, I fully accept who I am. -

צב | עב January Tevet | Sh’Vat Capricorn Saturn | Aquarius Saturn

צב | עב January Tevet | Sh’vat Capricorn Saturn | Aquarius Saturn Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 | 17th of Tevet* 2 | 18th of Tevet* New Year’s Day Parashat Vayechi Abraham Moshe Hillel Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech of Dinov Rabbi Salman Mutzfi Rabbi Huna bar Mar Zutra & Rabbi Rabbi Yaakov Krantz Mesharshya bar Pakod Rabbi Moshe Kalfon Ha-Cohen of Jerba 3 | 19th of Tevet * 4* | 20th of Tevet 5 | 21st of Tevet * 6 | 22nd of Tevet* 7 | 23rd of Tevet* 8 | 24th of Tevet* 9 | 25th of Tevet* Parashat Shemot Rabbi Menchachem Mendel Yosef Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon Rabbi Leib Mochiach of Polnoi Rabbi Hillel ben Naphtali Zevi Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi Rabbi Yaakov Abuchatzeira Rabbi Yisrael Dov of Vilednik Rabbi Schulem Moshkovitz Rabbi Naphtali Cohen Miriam Mizrachi Rabbi Shmuel Bornsztain Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler 10 | 26th of Tevet* 11 | 27th of Tevet* 12 | 28th of Tevet* 13* | 29th of Tevet 14* | 1st of Sh’vat 15* | 2nd of Sh’vat 16 | 3rd of Sh’vat* Rosh Chodesh Sh’vat Parashat Vaera Rabbeinu Avraham bar Dovid mi Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch HaRav Yitzhak Kaduri Rabbi Meshulam Zusha of Anipoli Posquires Rabbi Yehoshua Yehuda Leib Diskin Rabbi Menahem Mendel ben Rabbi Shlomo Leib Brevda Rabbi Eliyahu Moshe Panigel Abraham Krochmal Rabbi Aryeh Leib Malin 17* | 4th of Sh’vat 18 | 5th of Sh’vat* 19 | 6th of Sh’vat* 20 | 7th of Sh’vat* 21 | 8th of Sh’vat* 22 | 9th of Sh’vat* 23* | 10th of Sh’vat* Parashat Bo Rabbi Yisrael Abuchatzeirah Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Teitelbaum Rabbi Nathan David Rabinowitz