Beyond Populism European Politics in an Age of Fragmentation and Disruption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initiative of President Andrzej Duda Regarding the Change of the Constitution

Teka of Political Science and International Relations – OL PAN/UMCS, 2018, 13/1 DOI: 10.17951/teka.2018.13.1.25-34 INITIATIVE OF PRESIDENT ANDRZEJ DUDA REGARDING THE CHANGE OF THE CONSTITUTION Bożena Dziemidok-Olszewska Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin Faculty of Political Science, Department of Political Systems e-mail: [email protected] Marta Michalczuk-Wlizło Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin Faculty of Political Science, Department of Political Systems e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The objective of the article is to present and evaluate the initiative of President Andrzej Duda regarding the amendment of the Constitution, with which he appeared on 3 May 2017. The activities and presentations of the President in this regard during the previous year and related problems were all demonstrated. The controversies regarding the presidential initiative were di- vided into legal and political. Legal one is the regulation of the institution of referendum in the Constitution of 1997, the political ones result from the opinion and concepts of parties and citizens about the constitution and referendum in its case. Keywords: change of constitution, president, referendum, political science INTRODUCTION During the last year, from 3 May 2017 to 3 May 2018, we witnessed the, still incomplete, process of President Andrzej Duda’s activities regarding the referendum on the amendment to the Constitution of the Republic of Poland. The aim of the article is to present and assess the President’s activities in this area, and also to demonstrate the reactions to the President’s initiative. The research question is the justification, meaningfulness and effectiveness of the presidential initiative; the research hypothesis is the claim that the President’s actions are odd and irrational (pointless). -

Freedom House

7/14/2020 Slovakia | Freedom House FREEDOM IN THE WORLD 2020 Slovakia 88 FREE /100 Political Rights 36 /40 Civil Liberties 52 /60 LAST YEAR'S SCORE & STATUS 88 /100 Free Global freedom statuses are calculated on a weighted scale. See the methodology. TOP https://freedomhouse.org/country/slovakia/freedom-world/2020 1/15 7/14/2020 Slovakia | Freedom House Overview Slovakia’s parliamentary system features regular multiparty elections and peaceful transfers of power between rival parties. While civil liberties are generally protected, democratic institutions are hampered by political corruption, entrenched discrimination against Roma, and growing political hostility toward migrants and refugees. Key Developments in 2019 In March, controversial businessman Marian Kočner was charged with ordering the 2018 murder of investigative reporter Ján Kuciak and his fiancée. After phone records from Kočner’s cell phone were leaked by Slovak news outlet Aktuality.sk, an array of public officials, politicians, judges, and public prosecutors were implicated in corrupt dealings with Kočner. Also in March, environmental activist and lawyer Zuzana Čaputová of Progressive Slovakia, a newcomer to national politics, won the presidential election, defeating Smer–SD candidate Maroš Šefčovič. Čaputová is the first woman elected as president in the history of the country. Political Rights A. Electoral Process A1 0-4 pts Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 TOP Slovakia is a parliamentary republic whose prime minister leads the government. There is also a directly elected president with important but limited executive powers. In March 2018, an ultimatum from Direction–Social Democracy (Smer–SD), a https://freedomhouse.org/country/slovakia/freedom-world/2020 2/15 7/14/2020 Slovakia | Freedom House junior coalition partner, and center-right party Most-Híd, led to the resignation of former prime minister Robert Fico. -

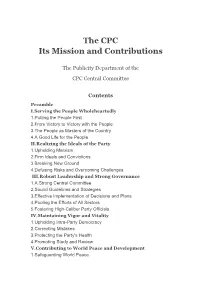

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions

The CPC Its Mission and Contributions The Publicity Department of the CPC Central Committee Contents Preamble I.Serving the People Wholeheartedly 1.Putting the People First 2.From Victory to Victory with the People 3.The People as Masters of the Country 4.A Good Life for the People II.Realizing the Ideals of the Party 1.Upholding Marxism 2.Firm Ideals and Convictions 3.Breaking New Ground 4.Defusing Risks and Overcoming Challenges III.Robust Leadership and Strong Governance 1.A Strong Central Committee 2.Sound Guidelines and Strategies 3.Effective Implementation of Decisions and Plans 4.Pooling the Efforts of All Sectors 5.Fostering High-Caliber Party Officials IV.Maintaining Vigor and Vitality 1.Upholding Intra-Party Democracy 2.Correcting Mistakes 3.Protecting the Party's Health 4.Promoting Study and Review V.Contributing to World Peace and Development 1.Safeguarding World Peace 2.Pursuing Common Development 3.Following the Path of Peaceful Development 4.Building a Global Community of Shared Future Conclusion Preamble The Communist Party of China (CPC), founded in 1921, has just celebrated its centenary. These hundred years have been a period of dramatic change – enormous productive forces unleashed, social transformation unprecedented in scale, and huge advances in human civilization. On the other hand, humanity has been afflicted by devastating wars and suffering. These hundred years have also witnessed profound and transformative change in China. And it is the CPC that has made this change possible. The Chinese nation is a great nation. With a history dating back more than 5,000 years, China has made an indelible contribution to human civilization. -

Unter Europäischen Sozialdemokraten – Wer Weist Den Weg Aus Der Krise? | Von Klaus Prömpers Von Der Partie

DER HAUPTSTADTBRIEF 23. WOCHE AM SONNTAG 09.JUNI 2019 DIE KOLUMNE Rückkehr zu außenpolitischen Fundamenten AM SONNTAG Die Reise des Bundespräsidenten nach Usbekistan zeigt, wie wichtig die Schnittstelle zwischen Europa und Asien ist | Von Manfred Grund und Dirk Wiese Sonstige Vereinigung ie wichtig Zentralasien für Mirziyoyev ermutigen, „auf diesem Weg Europa ist, hat Frank-Walter entschlossen weiterzugehen“. Steinmeier WSteinmeier früh erkannt. Im und Mirziyoyev kannten sich bereits vom November 2006 bereiste er als erster Au- Berlin-Besuch des usbekischen Präsidenten GÜNTER ßenminister aus einem EU-Mitgliedsland im Januar 2019 – dem ersten eines usbeki- BANNAS BERND VON JUTRCZENKA/DPABERND VON alle fünf zentralasiatischen Staaten. Er schen Staatsoberhaupts seit 18 Jahren. PRIVAT wollte damals ergründen, wie die Euro- Die Bedeutung Zentralasiens für Europa päische Union mit der Region zusammen- hat seit 2007 weiter zugenommen. Zugleich ist Kolumnist des HAUPTSTADTBRIEFS. Bis März 2018 war er Leiter der Berliner arbeiten könne, die – so war ihm schon hat sich die geopolitische Schlüsselregion – Redaktion der Frankfurter Allgemeinen damals klar – „einfach zu wichtig ist, als Usbekistan zeigt es – grundlegend verändert. Zeitung. Hier erinnert er an die politisch dass wir sie an den Rand unseres Wahr- Die EU-Kommission und die Hohe Vertrete- vielgestaltige Gründungsphase der nehmungsspektrums verdrängen.“ Ein rin der EU für Außen- und Sicherheitspoli- Grünen vor 40 Jahren. halbes Jahr später nahm die EU auf Initi- tik haben diesen Entwicklungen Rechnung ative der deutschen Ratspräsidentschaft getragen und am 15. Mai eine überarbeitete die Strategie „EU und Zentralasien – eine Zentralasienstrategie vorgestellt. Unter dem nfang kommenden Jahres wer- Partnerschaft für die Zukunft“ (kurz: EU- Titel „New Opportunities for a Stronger Part- Aden die Grünen ihrer Grün- Zentralasienstrategie) an. -

Opposition Behaviour Against the Third Wave of Autocratisation: Hungary and Poland Compared

European Political Science https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00325-x SYMPOSIUM Opposition behaviour against the third wave of autocratisation: Hungary and Poland compared Gabriella Ilonszki1 · Agnieszka Dudzińska2 Accepted: 4 February 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Hungary and Poland are often placed in the same analytical framework from the period of their ‘negotiated revolutions’ to their autocratic turn. This article aims to look behind this apparent similarity focusing on opposition behaviour. The analysis demonstrates that the executive–parliament power structure, the vigour of the extra- parliamentary actors, and the opposition party frame have the strongest infuence on opposition behaviour, and they provide the sources of diference between the two country cases: in Hungary an enforced power game and in Poland a political game constrain opposition opportunities and opposition strategic behaviour. Keywords Autocratisation · Extra-parliamentary arena · Hungary · Opposition · Parliament · Party system · Poland Introduction What can this study add? Hungary and Poland are often packed together in political analyses on the grounds that they constitute cases of democratic decline. The parties in governments appear infamous on the international, particularly on the EU, scene. Fidesz1 in Hungary has been on the verge of leaving or being forced to leave the People’s Party group due to repeated abuses of democratic norms, and PiS in Poland2 is a member of 1 The party’s full name now reads Fidesz—Hungarian Civic Alliance. 2 Abbreviation of Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice). * Gabriella Ilonszki [email protected] Agnieszka Dudzińska [email protected] 1 Department of Political Science, Corvinus University of Budapest, 8 Fővám tér, Budapest 1093, Hungary 2 Institute of Sociology, University of Warsaw, Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28, 00-927 Warsaw, Poland Vol.:(0123456789) G. -

European Left Info Flyer

United for a left alternative in Europe United for a left alternative in Europe ”We refer to the values and traditions of socialism, com- munism and the labor move- ment, of feminism, the fem- inist movement and gender equality, of the environmental movement and sustainable development, of peace and international solidarity, of hu- man rights, humanism and an- tifascism, of progressive and liberal thinking, both national- ly and internationally”. Manifesto of the Party of the European Left, 2004 ABOUT THE PARTY OF THE EUROPEAN LEFT (EL) EXECUTIVE BOARD The Executive Board was elected at the 4th Congress of the Party of the European Left, which took place from 13 to 15 December 2013 in Madrid. The Executive Board consists of the President and the Vice-Presidents, the Treasurer and other Members elected by the Congress, on the basis of two persons of each member party, respecting the principle of gender balance. COUNCIL OF CHAIRPERSONS The Council of Chairpersons meets at least once a year. The members are the Presidents of all the member par- ties, the President of the EL and the Vice-Presidents. The Council of Chairpersons has, with regard to the Execu- tive Board, rights of initiative and objection on important political issues. The Council of Chairpersons adopts res- olutions and recommendations which are transmitted to the Executive Board, and it also decides on applications for EL membership. NETWORKS n Balkan Network n Trade Unionists n Culture Network Network WORKING GROUPS n Central and Eastern Europe n Africa n Youth n Agriculture n Migration n Latin America n Middle East n North America n Peace n Communication n Queer n Education n Public Services n Environment n Women Trafficking Member and Observer Parties The Party of the European Left (EL) is a political party at the Eu- ropean level that was formed in 2004. -

Address by President of the Republic of Poland Mr Andrzej Duda On

Address by President of the Republic of Poland Mr Andrzej Duda on the occasion of the New Year`s meeting with the Diplomatic Corps Presidential Palace, 14 January 2019 Your Excellency, Most Reverend Sir, Dean of the Diplomatic Corps, Your Excellencies, the Ambassadors, Honourable Marshal, Honourable Prime Ministers, Excellencies, Most Reverend Bishops, Honourable Ministers, Madam Justice of the Constitutional Court, Generals, Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, It is my great pleasure to welcome you to our fourth joint New Year`s meeting. 2018 is over, a year rich in numerous events, out of which the most significant, truly momentous ones for us, were undoubtedly the celebrations of the centenary of regaining independence. I wish to thank you warmly for making our jubilee visible also in your home countries; it was often an occasion for grand festivities and joy. Last year we commenced our 2-year-long, non-permanent membership of the United Nations Security Council, whereas in Katowice we presided over the session of the 24th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Its successful outcome was reflected in the adoption of the so called Katowice Rulebook, which was possible thanks to the readiness for compromise demonstrated by all parties participating in the negotiations. I would like to thank your countries for cooperation and for expressing acknowledgment of our good and effective organization of the Katowice conference. The year 2018 was marked, once again, by high level of my international activity. Throughout the whole year I paid 26 foreign visits, and met with more than 20 international leaders who visited Poland. -

Now British and Irish Communist Organisation

THE I C PG ·B NOW BRITISH AND IRISH COMMUNIST ORGANISATION From its foundation until the late 1940s, the Communist Party of Great Britain set itself a very clear political task - to lead the British working class. Its justification was that the working class required the abolition of capitalism for its emancipation, and only the Communist Party was able and willing to lead the working class in undertaking this. l'he CP recognised that it might have to bide its time before a seizure of power was practicable, mainly, it believed, because the working class .' consciousness was not yet revol utionary. But its task was still to lead the working class: only by leading the working class in the immediate, partial day-to-day class struggle could the CP hope to show that the abolition of capitalism was the real solution to their griev ances. It was through such struggle that the proletariat would learn; and without the Communist Party to point out lead the Left of the Labour Party to abolish c~pitalism: The 'll lacked the vital understand~ng and w~ll to the lessons of the struggle, the proletariat would draw only Labour Party s t 1 . · partial and superficial conclusions from its experience. · L ft Labour was open to Commun~st 1nf1 uence. do th~s. But e h · ld cooperate with the Labour Party because t e Commun~sts cou , h d h By the mid-1930s, the Communist Party was compelled to ack · 't f the Labour Party s members also a t e vast maJor~ Y o 1 nowledge that the Labour Party had gained the allegiance of . -

Poland's 2019 Parliamentary Election

— SPECIAL REPORT — 11/05/2019 POLAND’S 2019 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION Tomasz Grzegorz Grosse Warsaw Institute POLAND’S 2019 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION Held on October 13, 2019, Poland’s general election is first and foremost a success of democracy, as exemplified by crowds rushing to polling stations and a massive rise in voter turnout. Those that claimed victory were the govern- ment groups that attracted a considerable electorate, winning in more constitu- encies across the country they ruled for the past four years. Opposition parties have earned a majority in the Senate, the upper house of the Polish parliament. A fierce political clash turned into deep chasms throughout the country, and Poland’s political stage reveals polarization between voters that lend support to the incumbent government and those that question the authorities by manifest- ing either left-liberal or far-right sentiments. Election results Poland’s parliamentary election in 2019 attrac- try’s 100-seat Senate, the upper house of the ted the attention of Polish voters both at home parliament, it is the Sejm where the incum- and abroad while drawing media interest all bents have earned a majority of five that has over the world. At stake were the next four a pivotal role in enacting legislation and years in power for Poland’s ruling coalition forming the country’s government2. United Right, led by the Law and Justice party (PiS)1. The ruling coalition won the election, The electoral success of the United Right taking 235 seats in Poland’s 460-seat Sejm, the consisted in mobilizing its supporters to a lower house of the parliament. -

Transcript (PDF)

Podcast Episode Season 1, Episode 15: In Conversation with Theo Koll From the ULI Germany: Real Estate ??? Cities ??? People Date: September 04, 2020 00:00:00 --> 00:00:04: Real estate provided people of the USA Germany Podcast co-creators 00:00:04 --> 00:00:06: of the built environment, 00:00:06 --> 00:00:10: creators of the real estate industry 00:00:10 --> 00:00:12: and personalities who shape our cities. 00:00:12 --> 00:00:18: Real estate, cities, people this common thread runs through our 00:00:18 --> 00:00:18: programs, 00:00:18 --> 00:00:22: our podcasts and of course also through the evening song 00:00:23 --> 00:00:27: Sammet what distinguishes the Julei from other organizations? 00:00:27 --> 00:00:33: We consistently look at all real estate issues in an 00:00:33 --> 00:00:37: urban context and always focus on people. 00:00:37 --> 00:00:42: The actions of the industry of all of us are 00:00:42 --> 00:00:44: socially relevant. 00:00:44 --> 00:00:48: So who, if I do the Julei, should also examine 00:00:48 --> 00:00:52: all socially relevant topics and not only look outside the 00:00:52 --> 00:00:52: box, 00:00:52 --> 00:00:55: but also think and act? 00:00:55 --> 00:00:59: The world is not only in turmoil since today, 00:00:59 --> 00:01:07: but today, in September 2020, we feel this particularly intensely. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions.