The Art of Popular Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Art's Sake

GHENT UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF ARTS AND PHILOSOPHY 2008-2009 FOR ART’S SAKE COMPARISON OF OSCAR WILDE‘S THE PICTURE OF DORIAN GRAY AND OUIDA‘S UNDER TWO FLAGS Hanne Lapierre May 2009 Supervisor: Paper submitted in partial Dr. Kate Macdonald fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of ―Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels-Spaans‖. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Kate Macdonald who oversaw the building up of the main body of the text. Her remarks were very helpful for writing the final version of this paper. I also thank Dr. Andrew King for giving me access to some of his interesting books on Ouida and for his remarkable enthusiasm on the subject. Contents Acknowledgements 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................1 2. On Ouida…………………………………………………………………4 3. Aestheticism……………………………………………………………..13 3.1. Introducing Aestheticism 13 3.2. The Origins of Aestheticism 15 3.3. Aspects of Aestheticism 17 3.3.1. Aestheticism as a View of Life 17 3.3.2. Aestheticism as a View of Art 21 3.3.2.1. The extraordinary status of the artist 21 3.3.2.2. An unlimited devotion to art 23 3.3.2.3. Rejection of conventional moral values 24 3.3.2.4. Superiority of form over content 30 3.3.2.5. Conclusion 33 4. Consumer Culture……………………………………………………...34 4.1. The Rise of Consumer Culture 34 4.2. Advertising 42 4.3. The Commodity 49 4.3.1. Use Value and Exchange Value 49 4.3.2. Being vs. Having 52 4.3.3. Having vs. Appearing 53 4.4. -

Framley Parsonage: the Chronicles of Barsetshire Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FRAMLEY PARSONAGE: THE CHRONICLES OF BARSETSHIRE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anthony Trollope,Katherine Mullin,Francis O'Gorman | 528 pages | 01 Dec 2014 | Oxford University Press | 9780199663156 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Framley Parsonage: The Chronicles of Barsetshire PDF Book It is funny too, because I remember the first time I read this series almost 20 years ago I did not appreciate the last four nearly so much at the first two. This first-ever bio… More. Start your review of Framley Parsonage Chronicles of Barsetshire 4. George Gissing was an English novelist, who wrote twenty-three novels between and I love the wit, variety and characterisation in the series and this wonderful book is no exception. There is no cholera, no yellow-fever, no small-pox, more contagious than debt. Troubles visit the Robarts in the form of two main plots: one financial, and one romantic. The other marriage is that of the outspoken heiress, Martha Dunstable, to Doctor Thorne , the eponymous hero of the preceding novel in the series. For all the basic and mundane humanity of its story, one gets flashes of steel, and darkness, behind all the Barsetshirian goodness. But this is not enough for Mark whose ambitions lie beyond the small parish of Framley. Lucy, much like Mary Thorne in Doctor Thorne acts precisely within appropriate boundaries, but also speaks her mind and her conduct does much towards securing her own happiness. Lucy's conduct and charity especially towards the family of poor priest Josiah Crawley weaken her ladyship's resolve. Audio MP3 on CD. On the romantic side there are also some more love stories with a lot less passion, starring some of our acquaintances. -

Dickens, Trollope, Thackeray and First-Person

‘ALLOW ME TO INTRODUCE MYSELF — FIRST, NEGATIVELY’: CHARLES DICKENS, ANTHONY TROLLOPE, WILLIAM MAKEPEACE THACKERAY AND FIRST-PERSON JOURNALISM IN THE 1860S FAMILY MAGAZINE HAZEL MACKENZIE PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND RELATED LITERATURE SEPTEMBER 2010 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the editorial contributions of W.M. Thackeray, Charles Dickens and Anthony Trollope to the Cornhill Magazine, All the Year Round and Saint Pauls Magazine, analyzing their cultivation of a familiar or personal style of journalism in the context of the 1860s family magazine and its rhetoric of intimacy. Focusing on their first-person journalistic series, it argues that these writers/editors used these contributions as a means of establishing a seemingly intimate and personal relationship with their readers, and considers the various techniques that they used to develop that relationship, including their use of first-person narration, autobiography, the anecdote, dream sequences and memory. It contends that those same contributions questioned and critiqued the depiction of reader-writer relations which they simultaneously propagated, highlighting the distinction between this portrayal and the realities of the industrialized and commercialized world of periodical journalism. It places this within the context of the discourse of family that was integral to the identity of these magazines, demonstrating how these series both held up and complicated the idealized image of Victorian domesticity that was promoted by the mainstream periodical culture of the day, maintaining that this was a standard feature of family magazine journalism and theorizing that this was in fact a large part of its popular appeal to the family market. The introductory chapter examines the discourse of family that dominated the mid-range magazines of the 1860s and how this ties in with the series’ rhetoric of intimacy. -

Forgers and Fiction: How Forgery Developed the Novel, 1846-79

Forgers and Fiction: How Forgery Developed the Novel, 1846-79 Paul Ellis University College London Doctor of Philosophy UMI Number: U602586 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602586 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 Abstract This thesis argues that real-life forgery cases significantly shaped the form of Victorian fiction. Forgeries of bills of exchange, wills, parish registers or other documents were depicted in at least one hundred novels between 1846 and 1879. Many of these portrayals were inspired by celebrated real-life forgery cases. Forgeries are fictions, and Victorian fiction’s representations of forgery were often self- reflexive. Chapter one establishes the historical, legal and literary contexts for forgery in the Victorian period. Chapter two demonstrates how real-life forgers prompted Victorian fiction to explore its ambivalences about various conceptions of realist representation. Chapter three shows how real-life forgers enabled Victorian fiction to develop the genre of sensationalism. Chapter four investigates how real-life forgers influenced fiction’s questioning of its epistemological status in Victorian culture. -

Publishing Swinburne; the Poet, His Publishers and Critics

UNIVERSITY OF READING Publishing Swinburne; the poet, his publishers and critics. Vol. 1: Text Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Language and Literature Clive Simmonds May 2013 1 Abstract This thesis examines the publishing history of Algernon Charles Swinburne during his lifetime (1837-1909). The first chapter presents a detailed narrative from his first book in 1860 to the mid 1870s: it includes the scandal of Poems and Ballads in 1866; his subsequent relations with the somewhat dubious John Camden Hotten; and then his search to find another publisher who was to be Andrew Chatto, with whom Swinburne published for the rest of his life. It is followed by a chapter which looks at the tidal wave of criticism generated by Poems and Ballads but which continued long after, and shows how Swinburne responded. The third and central chapter turns to consider the periodical press, important throughout his career not just for reviewing but also as a very significant medium for publishing poetry. Chapter 4 on marketing looks closely at the business of producing and of selling Swinburne’s output. Finally Chapter 5 deals with some aspects of his career after the move to Putney, and shows that while Theodore Watts, his friend and in effect his agent, was making conscious efforts to reshape the poet, some of Swinburne’s interests were moving with the tide of public taste; how this was demonstrated in particular by his volume of Selections and how his poetic oeuvre was finally consolidated in the Collected Edition at the end of his life. -

Individualism, the New Woman, and Marriage in the Novels of Mary Ward, Sarah Grand, and Lucas Malet Tapanat Khunpakdee Departmen

Individualism, the New Woman, and marriage in the novels of Mary Ward, Sarah Grand, and Lucas Malet Tapanat Khunpakdee Department of English Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English 2013 1 Individualism, the New Woman, and marriage in the novels of Mary Ward, Sarah Grand, and Lucas Malet Tapanat Khunpakdee Department of English Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English 2013 2 Declaration of Authorship I, Tapanat Khunpakdee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 17 June, 2013 3 Abstract This thesis focuses upon the relationship between individualism, the New Woman, and marriage in the works of Mary Ward, Sarah Grand, and Lucas Malet. In examining how these three popular novelists of the late nineteenth century responded to the challenge of female individualism, this thesis traces the complex afterlife of John Stuart Mill’s contribution to Victorian feminism. The thesis evaluates competing models of liberty and the individual – freedom and self-development – in the later nineteenth century at the outset and traces how these differing models work their way through the response of popular writers on the Woman Question. Ward’s Robert Elsmere (1888) and Marcella (1894) posit an antagonism between the New Woman’s individualism and marriage. She associates individualism with selfishness, which explicates her New Woman characters’ personal and ideological transformation leading to marriage. The relinquishing of individualism suggests Ward’s ambivalent response to the nineteenth-century Woman Question. -

Trollopiana 100 Free Sample

THE JOURNAL OF THE Number 100 ~ Winter 2014/15 Bicentenary Edition EDITORIAL ~ 1 Contents Editorial Number 100 ~ Winter 2014-5 his 100th issue of Trollopiana marks the beginning of our FEATURES celebrations of Trollope’s birth 200 years ago on 24th April 1815 2 A History of the Trollope Society Tat 16 Keppel Street, London, the fourth surviving child of Thomas Michael Helm, Treasurer of the Trollope Society, gives an account of the Anthony Trollope and Frances Milton Trollope. history of the Society from its foundation by John Letts in 1988 to the As Trollope’s life has unfolded in these pages over the years present day. through members’ and scholars’ researches, it seems appropriate to begin with the first of a three-part series on the contemporary criticism 6 Not Only Ayala Dreams of an Angel of Light! If you have ever thought of becoming a theatre angel, now is your his novels created, together with a short history of the formation of our opportunity to support a production of Craig Baxter’s play Lady Anna at Society. Sea. During this year we hope to reach a much wider audience through the media and publications. Two new books will be published 7 What They Said About Trollope At The Time Dr Nigel Starck presents the first in a three-part review of contemporary by members: Dispossessed, the graphic novel based on John Caldigate by critical response to Trollope’s novels. He begins with Part One, the early Dr Simon Grennan and Professor David Skilton, and a new full version years of 1847-1858. -

Mrs Henry Wood’, an Equal Focus Is Afforded to the Other Literary Identities Under Which Wood Operated During Her Illustrious Career

The professional identities of Ellen Wood Item Type Thesis or dissertation Authors Holland, Chloe Publisher University of Chester Download date 25/09/2021 17:26:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/311965 This work has been submitted to ChesterRep – the University of Chester’s online research repository http://chesterrep.openrepository.com Author(s): Chloe Holland Title: The professional identities of Ellen Wood Date: 2013 Originally published as: University of Chester MA dissertation Example citation: Holland, C. (2013). The professional identities of Ellen Wood. (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Chester, United Kingdom. Version of item: Submitted version Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10034/311965 University of Chester Department of English MA Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture EN7204 Dissertation G33541 The Professional Identities of Ellen Wood 1 Abstract As author of the 1861 bestseller, East Lynne, Ellen Wood forged a successful literary career as a prolific writer of sensation fiction and celebrity-editor of The Argosy magazine. While this project will examine the construction and maintenance, of her most famous persona, the pious, conservative ‘Mrs Henry Wood’, an equal focus is afforded to the other literary identities under which Wood operated during her illustrious career. Although recent scholars have considered the business-like tenacity of Wood as a commercially driven writer in contrast to the fragile, conservative ‘Mrs Henry Wood’ persona, this dissertation integrates the identities forged in the early anonymous writings in periodicals and publications made under male pseudonyms with these contrasting representations to procure a comprehensive view of the literary identities adopted by Wood. Situating Wood in the context of her contemporaries, the role of the female writer in the mid-nineteenth-century is primarily outlined to inform Wood’s development of anonymous identities as a periodical writer through the semi-anonymous signature in contributions during the 1850s which foregrounded the ‘Mrs Henry Wood’ persona. -

Download Book \\ a Day of Pleasure: a Wonderful Novel (Paperback) ~ D6KIJVCZZDC7

IPNNUQ3X5KAF ~ Doc ^ A Day of Pleasure: A Wonderful Novel (Paperback) A Day of Pleasure: A Wonderful Novel (Paperback) Filesize: 5.15 MB Reviews This is actually the finest ebook i have got study till now. I actually have go through and that i am sure that i am going to likely to read once again once again later on. Its been developed in an extremely straightforward way and is particularly simply soon after i finished reading through this ebook through which actually modified me, change the way i really believe. (Mrs. Maybelle O'Conner) DISCLAIMER | DMCA I9PPQKQ39LV6 < Kindle # A Day of Pleasure: A Wonderful Novel (Paperback) A DAY OF PLEASURE: A WONDERFUL NOVEL (PAPERBACK) To get A Day of Pleasure: A Wonderful Novel (Paperback) eBook, please access the hyperlink below and save the document or get access to additional information which might be in conjuction with A DAY OF PLEASURE: A WONDERFUL NOVEL (PAPERBACK) ebook. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, United States, 2015. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 229 x 152 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****. A Wonderful Novel A Day of PleasureEllen Wood Ellen Wood (17 January 1814 - 10 February 1887), was an English novelist, better known as Mrs. Henry Wood. She is perhaps remembered most for her 1861 novel East Lynne, but many of her books became international best-sellers, being widely received in the United States and surpassing Charles Dickens fame in Australia.Ellen Price was born in Worcester in 1814. In 1836 she married Henry Wood, who worked in the banking and shipping trade in Dauphine in the South of France, where they lived for 20 years. -

This Is the File GUTINDEX.ALL Updated to July 5, 2013

This is the file GUTINDEX.ALL Updated to July 5, 2013 -=] INTRODUCTION [=- This catalog is a plain text compilation of our eBook files, as follows: GUTINDEX.2013 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2013 with eBook numbers starting at 41750. GUTINDEX.2012 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2012 with eBook numbers starting at 38460 and ending with 41749. GUTINDEX.2011 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011 with eBook numbers starting at 34807 and ending with 38459. GUTINDEX.2010 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2010 with eBook numbers starting at 30822 and ending with 34806. GUTINDEX.2009 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2009 with eBook numbers starting at 27681 and ending with 30821. GUTINDEX.2008 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2008 with eBook numbers starting at 24098 and ending with 27680. GUTINDEX.2007 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2007 with eBook numbers starting at 20240 and ending with 24097. GUTINDEX.2006 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2006 with eBook numbers starting at 17438 and ending with 20239. -

Cigarette's Healing Power in Ouida's Under Two Flags

22 INOCULATION AND EMPIRE : CIGARETTE 'S HEALING POWER IN OUIDA 'S UNDER TWO FLAGS J. Stephen Addcox (University of Florida) Abstract As the popular literature of the nineteenth century receives more attention from scholars, Ouida’s novels have grown more appealing to those interested in exploring the many forms of the Victorian popular novel. Under Two Flags is perhaps her most well-known work, and this fame stems in part from the character of Cigarette, who fights like a man while also maintaining her status as a highly desirable woman in French colonial Africa. Whilst several scholars have argued that Ouida essentially undermines Cigarette as a feminine and feminist character, I argue that it is possible to read Cigarette as a highly positive element in the novel. This is demonstrated in the ways that Cigarette’s actions are based on a very feminine understanding of medicine, as Ouida draws on contemporary and historical developments in medicinal technology to develop a metaphorical status for Cigarette as a central figure of healing. Specifically, we see that Cigarette takes on the form of an inoculation for the male protagonist’s (Bertie Cecil) downfall. In this way, I hope to offer a view of Ouida’s text that does not read her famous character as merely an “almost-but-not-quite” experiment. I. Introduction Among all of Ouida’s novels, it is Cigarette from Under Two Flags (1867) who has remained one of her most memorable and notorious characters. In the twentieth century Ouida’s biographer Yvonne Ffrench evaluated Cigarette as ‘absolutely original and perfectly realised’. -

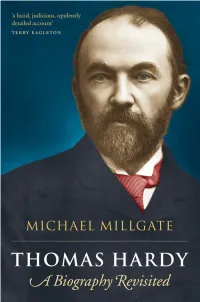

Thomas-Hardy-A-Biography-Revisited-Pdfdrivecom-45251581745719.Pdf

THOMAS HARDY This page intentionally left blank THOMAS HARDY MICHAEL MILLGATE 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford 2 6 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Michael Millgate 2004 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2004 First published in paperback 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data applied for Typeset by Regent Typesetting, London Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Antony Rowe, Chippenham ISBN 0–19–927565–3 978–0–19–927565–6 ISBN 0–19–927566–1 (Pbk.) 978–0–19–927566–3 (Pbk.) 13579108642 To R.L.P.