Political Representation & Social Inclusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

India's Domestic Political Setting

Updated July 12, 2021 India’s Domestic Political Setting Overview The BJP and Congress are India’s only genuinely national India, the world’s most populous democracy, is, according parties. In previous recent national elections they together to its Constitution, a “sovereign, socialist, secular, won roughly half of all votes cast, but in 2019 the BJP democratic republic” where the bulk of executive power boosted its share to nearly 38% of the estimated 600 million rests with the prime minister and his Council of Ministers votes cast (to Congress’s 20%; turnout was a record 67%). (the Indian president is a ceremonial chief of state with The influence of regional and caste-based (and often limited executive powers). Since its 1947 independence, “family-run”) parties—although blunted by two most of India’s 14 prime ministers have come from the consecutive BJP majority victories—remains a crucial country’s Hindi-speaking northern regions, and all but 3 variable in Indian politics. Such parties now hold one-third have been upper-caste Hindus. The 543-seat Lok Sabha of all Lok Sabha seats. In 2019, more than 8,000 candidates (House of the People) is the locus of national power, with and hundreds of parties vied for parliament seats; 33 of directly elected representatives from each of the country’s those parties won at least one seat. The seven parties listed 28 states and 8 union territories. The president has the below account for 84% of Lok Sabha seats. The BJP’s power to dissolve this body. A smaller upper house of a economic reform agenda can be impeded in the Rajya maximum 250 seats, the Rajya Sabha (Council of States), Sabha, where opposition parties can align to block certain may review, but not veto, revenue legislation, and has no nonrevenue legislation (see Figure 1). -

Guyana: an Overview

Updated March 10, 2020 Guyana: An Overview Located on the north coast of South America, English- system from independence until the early 1990s; the party speaking Guyana has characteristics common of a traditionally has had an Afro-Guyanese base of support. In Caribbean nation because of its British colonial heritage— contrast, the AFC identifies as a multiracial party. the country achieved independence from Britain in 1966. Guyana participates in Caribbean regional organizations The opposition People’s Progressive Party/Civic (PPP/C), and forums, and its capital of Georgetown serves as led by former President Bharrat Jagdeo (1999-2011), has 32 headquarters for the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), a seats in the National Assembly. Traditionally supported by regional integration organization. Indo-Guyanese, the PPP/C governed Guyana from 1992 until its defeat in the 2015 elections. Current congressional interest in Guyana is focused on the conduct of the March 2, 2020, elections. Some Members of Congress have expressed deep concern about allegations of Guyana at a Glance potential electoral fraud and have called on the Guyana Population: 782,000 (2018, IMF est.) Elections Commission (GECOM) to not declare a winner Ethnic groups: Indo-Guyanese, or those of East Indian until the completion of a credible vote tabulation process. heritage, almost 40%; Afro-Guyanese, almost 30%; mixed, 20%; Amerindian, almost 11% (2012, CIA est.) Figure 1. Map of Guyana Area: 83,000 square miles, about the size of Idaho GDP: $3.9 billion (current prices, 2018, IMF est.) Real GDP Growth: 4.1% (2018 est.); 4.4% (2019 est.) (IMF) Per Capita GDP: $4,984 (2018, IMF est.) Life Expectancy: 69.6 years (2017, WB) Sources: International Monetary Fund (IMF); Central Intelligence Agency (CIA); World Bank (WB). -

POLITICAL PARTIES DEVELOPMENT USAID Associate Cooperative Agreement No

CEPPS/NDI Quarterly Report: January 1 to March 31, 2005 BOLIVIA: POLITICAL PARTIES DEVELOPMENT USAID Associate Cooperative Agreement No. 511-A-00-04-00016-00, under the Leader Cooperative Agreement No. DGC-A-00-01-00004-00 Project dates: November 6, 2003, to June 30, 2005 I. SUMMARY Bolivia was once considered one of the most stable democracies in the Andes and a paragon of economic reform. Despite the implementation of major socio-economic reforms, economic disparity and ethnic and regional conflict have led to recent political turmoil. In November 2003, USAID awarded the National Democratic Institute a cooperative agreement to fulfill the following objectives: provide technical assistance for parties to comply with the 1999 Political Party Law; help parties improve candidate recruitment and selection practices; work with parties to improve relations with civil society; and strengthen party communication strategies and mechanisms to ensure that party proposals reflect citizen demands. Following several months of burgeoning road blockades and protests, President Carlos Mesa offered his resignation twice in March 2005. Similar economically motivated protests in October 2003 resulted in violence and led to the resignation of President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada. Although Lozada’s successor, President Mesa, has committed to completing his term through 2007, the country remains mired in historic conflicts that are severely hindering national governance. Amidst continued citizen-driven political pressure tactics, Bolivians must prepare for the first-ever popular selection of department prefects, a national referendum on regional autonomy and a constituent assembly process all scheduled for 2005 and 2006. The present conditions highlight the need to rebuild healthy and responsive political parties that can effectively channel citizen demands, offer policy alternatives, and provide avenues for all Bolivians to engage in constructive political participation. -

Unicameralism and the Indiana Constitutional Convention of 1850 Val Nolan, Jr.*

DOCUMENT UNICAMERALISM AND THE INDIANA CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1850 VAL NOLAN, JR.* Bicameralism as a principle of legislative structure was given "casual, un- questioning acceptance" in the state constitutions adopted in the nineteenth century, states Willard Hurst in his recent study of main trends in the insti- tutional development of American law.1 Occasioning only mild and sporadic interest in the states in the post-Revolutionary period,2 problems of legislative * A.B. 1941, Indiana University; J.D. 1949; Assistant Professor of Law, Indiana Uni- versity School of Law. 1. HURST, THE GROWTH OF AMERICAN LAW, THE LAW MAKERS 88 (1950). "O 1ur two-chambered legislatures . were adopted mainly by default." Id. at 140. During this same period and by 1840 many city councils, unicameral in colonial days, became bicameral, the result of easy analogy to state governmental forms. The trend was reversed, and since 1900 most cities have come to use one chamber. MACDONALD, AmER- ICAN CITY GOVERNMENT AND ADMINISTRATION 49, 58, 169 (4th ed. 1946); MUNRO, MUNICIPAL GOVERN-MENT AND ADMINISTRATION C. XVIII (1930). 2. "[T]he [American] political theory of a second chamber was first formulated in the constitutional convention held in Philadelphia in 1787 and more systematically developed later in the Federalist." Carroll, The Background of Unicameralisnl and Bicameralism, in UNICAMERAL LEGISLATURES, THE ELEVENTH ANNUAL DEBATE HAND- BOOK, 1937-38, 42 (Aly ed. 1938). The legislature of the confederation was unicameral. ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION, V. Early American proponents of a bicameral legislature founded their arguments on theoretical grounds. Some, like John Adams, advocated a second state legislative house to represent property and wealth. -

GUYANA Date of Elections: December 16, 1968 Characteristics Of

GUYANA Date of Elections: December 16, 1968 Characteristics of Parliament The National Assembly of Guyana comprises 53 deputies elected for a period of 5 years. The Speaker, who is elected by the Assembly, may be chosen either from those of its members who are not Min isters or Parliamentary Secretaries or from among persons who are not members of the Assembly but are qualified for election to it. Furthermore, under the amended Constitution of January 10, 1969*, the Governor-General may designate up to 6 Ministers from among non-members qualified for election, "or such greater number as Parliament may prescribe". These Ministers become ex-oflicio members of Parliament but are not entitled to vote. The last general elections were held on December 7, 1964. Electoral System All Guyanese citizens of both sexes, at least 21 years of age and resident in Guyana or abroad, are entitled to vote in general elections provided they are duly registered as electors. Commonwealth citi zens of the requisite age who have lived in Guyana for at least one year are also entitled to participate. Voters are furthermore re quired to be sound of mind and not to have been deprived of their civil or political rights by court order. Guyanese and Commonwealth citizens are eligible for election as members of the National Assembly provided they qualify as voters, * See Parliamentary Developments in the World, p. 13 37 2 Guyana have been resident in Guyana for at least 1 year, and are able to speak and read the English language with a degree of proficiency sufficient to enable them to take an active part in parliamentary proceedings. -

Sudan Opposition to the Government, Including

Country Policy and Information Note Sudan: Opposition to the government, including sur place activity Version 2.0 November 2018 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the basis of claim section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis of COI; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Asessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment on whether, in general: x A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm x A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) x A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory x Claims are likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and x If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts. Country of origin information The country information in this note has been carefully selected in accordance with the general principles of COI research as set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum Research and Documentation’s (ACCORD), Researching Country Origin Information – Training Manual, 2013. -

The Role of the Argentine Congress in the Treaty-Making Process - Latin America

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 67 Issue 2 Symposium on Parliamentary Participation in the Making and Operation of Article 10 Treaties June 1991 The Role of the Argentine Congress in the Treaty-Making Process - Latin America Jose Maria Ruda Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jose M. Ruda, The Role of the Argentine Congress in the Treaty-Making Process - Latin America, 67 Chi.- Kent L. Rev. 485 (1991). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol67/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE ROLE OF THE ARGENTINE CONGRESS IN THE TREATY-MAKING PROCESS Jose MARIA RUDA* I. INTRODUCTION The Argentine Constitution is one of the oldest in the Americas. It was adopted in 1853 and amended in 1860, 1866, 1898, and 1958. In 1949, during Per6n's first presidency, another constitution was adopted. But after the revolution that overthrew Per6n in 1955, the old 1853 Constitution was reinstated. Therefore, this 1853 Constitution with the subsequent amendments mentioned earlier is the present Constitution of the Argentine Republic. The adoption of the 1853 Constitution was the product of a long process. Several attempts to adopt a constitution for the country were made beginning in 1810, the date of the uprising against Spain, but they failed or the instruments adopted survived for only a short period. -

Women in Power

Women in power Women Women in power: challenges for the 21st century GENERAL MANUELA SAENZ (1797-1856) is the controversial GROUP OF WOMEN PARLIAMENTARIANS OF THE AMERICAS FIPA and challenging Ecuadorian patriot whose picture illustrates the cover of these memoirs. Her relationship to Simón Bolívar Quito, 11-12 August 2010 and her many services to the fights for Independence in Ecuador, Colombia and Peru won her recognition as “the liberator of the Liberator”. One of the often forgotten causes to which she devoted her efforts is the rights of women, and she is also renowned for her firm, feminist stance. She died in exile, and almost complete neglected in Paita, Peru, during a diphtheria outbreak. She was buried in a common grave, but her campaign in Pichincha and Ayacucho has not been forgotten. The current Ecuadorian President declared her century st “Honorable General” on 22 May 2007, thus acknowledging a 1 military rank already awarded to her in history books. Sketch of Manuela Sáenz, by Oswaldo Guayasamín © Sucesión Guayasamín Challenges for the 2 Challenges for GRouP of WomEN PaRlIamENTaRIaNS of ThE amERIcaS fIPa PRESIDENT Linda Machuca Moscoso FINAL PROJECT DOCUMENTATION Gayne Villagómez Sandra Álvarez EDITORIAL COORDINATION AND PHOTOGRAPHY Directorate of Communication Ecuador’s National Assembly TITLE PAGE Sketch of Manuela Sáenz, by Oswaldo Guayasamín © Sucesión Guayasamín Assembly Member Linda Machuca Moscoso PRESIDENT DESIGN Luis Miguel Cáceres Verónica Ávila Diseño Editorial PRINTING Quito, 11-12 August 2010 FIRST EDITION Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador Quito, November 2010 TaBlE of coNTENTS I. Background 6 II. opening Remarks Foro Interparlamentario de las Américas Fórum Interparlamentar das Américas Licenciada Linda Machuca, President of the Group of Women Parliamentarians of the Americas 8 Mr. -

The Unicameral Legislature

Citizens Research Council of Michigan Council 810 FARWELL BUILDING -- DETROIT 26 204 BAUCH BUILDING -- LANSING 23 Comments Number 706 FORMERLY BUREAU OF GOVERNMENTAL RESEARCH February 18, 1960 THE UNICAMERAL LEGISLATURE By Charles W. Shull, Ph. D. Recurrence of the suggestion of a single-house legislature for Michigan centers attention upon the narrowness of choice in terms of the number of legislative chambers. Where representative assemblies exist today, they are either composed of two houses and are called bicameral, or they possess but a single unit and are known as unicameral. The Congress of the United States has two branches – the Senate and the House of Representatives. All but one of the present state legislatures – that of Nebraska – are bicameral. On the other hand, only a handful of municipal councils or county boards retain the two-chambered pattern. This has not always been the case. The colonial legislatures of Delaware, Georgia, and Pennsylvania were single- chambered or unicameral; Vermont came into the United States of America with a one-house lawmaking assem- bly, having largely formed her Constitution of 1777 upon the basis of that of Pennsylvania. Early city councils in America diversely copied the so-called “federal analogy” of two-chambers rather extensively in the formative days of municipal governmental institutions. The American Revolution of 1776 served as a turning point in our experimentation with state legislative struc- ture. Shortly after the Declaration of Independence, Delaware and Georgia changed from the single-chamber type of British colony days to the alternate bicameral form, leaving Pennsylvania and its imitator Vermont main- taining single-house legislatures. -

Historic Roots of the Legislative Branch

Historic Roots of the Legislative Branch Benjamin Franklin and Unicameralism Most delegates to the Constitutional Convention supported bicameralism, a legislature with two chambers. Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790), a delegate from Pennsylvania, was one of the exceptions. One of the arguments in favor of bicameralism was that one chamber should represent the wealthy class of society, while the other should represent all free men. In 1789, the state of Pennsylvania considered a change from unicameralism to bicameralism in its government. That year, Franklin wrote Queries and Remarks Respecting Alterations in the Constitution of Pennsylvania to record his opposition to bicameralism. The Combinations of Civil Society are not like those of a Set of Merchants, who club [combine] their Property in different Proportions for Building and Freighting a Ship, and may therefore have some Right to vote in the Disposition of the Voyage in greater or less Degree according to their respective Contributions; but the important ends of Civil Society, and the personal Securities of Life and Liberty, these remain the same in every Member of the society; and the poorest continues to have an equal Claim to them with the most opulent [wealthy], whatever Difference Time, Chance, or Industry may occasion in their Circumstances. On these Considerations, I am sorry to See the Signs this Paper I have been considering [the proposed Pennsylvania Constitution] affords, of a Disposition among some of our People to commence an Aristocracy, by giving the Rich a predominancy [superior power] in Government, a Choice peculiar to themselves in one half the Legislature to be proudly called the UPPER House, and the other Branch, chosen by the Majority of the People, degraded by the denomination [name] of the LOWER; and giving to this Upper a Permanency of four Years, and but two to the lower. -

Master Thesis Kjersti Monen Berge Juni2010

DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE POLITICS UNIVERSITY OF BERGEN ”We are equal, we are different” A social movements’ approach to the emergence of indigenous parties in Bolivia and Peru Master thesis Kjersti Monen Berge June 2010 Abstract This thesis discusses the emergence of ethnic, or indigenous, parties in Bolivia and Peru. More specifically, it seeks to explain why Bolivia has seen the emergence of indigenous-based political parties at the national level, while similar parties have so far only been successful at the local and regional levels in neighbouring Peru. The two cases share a number of attributes – most notably, both countries are Andean and they have large indigenous populations – but, significantly, differ on the dependent variable, emergence of indigenous parties. Using social movement theory and theory linking parties and social movements, this thesis tries to unite three differing focuses, or approaches, to explain the variation on the dependent variable. First, the “framing processes” approach focuses on the symbolic aspects of collective action, and development of indigenous-based discourses and their relations with other discourses, most relevantly here, the anti-neoliberal discourse. Second, the “mobilising structures” approach focuses more specifically on the organisational infrastructure of indigenous movements, while third, the “political opportunity” approach focuses on how political and institutional factors external to the social movements may encourage, or hinder, the development of indigenous parties. With this theoretical starting point, the thesis develops a model adapted to the Latin American context to explain the emergence of indigenous parties. The main variables that best explain the different development in the two cases are the following: First, in Bolivia, the ethnic discourse has prevailed within the indigenous movement, while, in Peru, the class-based discourse has been dominant. -

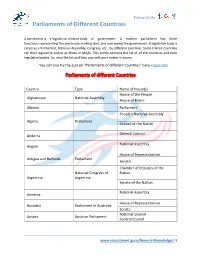

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly