Teaching Aqidah: Islamic Studies in Malaysia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

All About Ramadan What Is Ramadan? Ramadan Is a Religious Festival Celebrated by Muslims Which Lasts for 29 Or 30 Days

All about Ramadan What Is Ramadan? Ramadan is a religious festival celebrated by Muslims which lasts for 29 or 30 days. It is in the ninth month of the lunar calendar. Muslims believe that Ramadan is a time to remember when the Qur’an was revealed by the Prophet Muhammad. What Do Muslims Do During Ramadan? • They go to the mosque more often. • They read the Qur’an more regularly. • They try to give up bad habits. • They give money to charity. • They fast during daylight hours. This means they won’t eat or drink between sunrise and sunset. Why Do People Fast During Ramadan? People fast during Ramadan as a way of learning to wait for things and to have empathy and understanding for people who do not have as much as themselves. Fasting is difficult and young, old or unwell people do not have to fast. What Happens at the End of Ramadan? At the end of Ramadan, there is a 3-day celebration called Eid al-Fitr. Friends and family gather together to pray and share meals and gifts. Food is also given to the poor. Page 1 of 3 All about Ramadan Key Words • Muslims - a follower of Islam who believes that there is one true God called Allah • pilgrimage - a religious journey • Qur’an - the holy book for Muslim people The Five Pillars of Islam Salat: Hajj: Shahada: Zakat: Sawm: Prayer, Pilgrimage Faith Five times Charity Fasting to Mecca a day These are the five things you must remember to be a good Muslim. Page 2 of 3 All about Ramadan Questions 1. -

The Five Pillars of Islam

The Five Pillars of Islam Objectives: I will be able to describe the basic beliefs of Islam and explain the meaning of each of the Five Pillars of Islam. I will compare and contrast the Five Pillars of Islam with the duties of Catholicism. Materials: ● Station Note Taking Guide for students ● Primary Source Documents for each student station ● Construction paper (11x17) ● Colored pencils ● Rulers Technology: ● Computer ● SmartBoard ● Personal student devices Procedures: 1. Whole Group Share: What do you know about Islam? 2. Introductory Video: Students will watch “5 Pillars of Islam - part 1 | Cartoon by Discover Islam UK” (https://youtu.be/9hW3hH9_7pI) and “5 Pillars of Islam - part 2 | Cartoon by Discover Islam UK” (https://youtu.be/_bujwCZ9RHI) 3. Small Group Activity: Students will work in small groups of 4-5 and rotate between five stations (see below) and complete 5 Pillars of Islam note taking guide. a. Declaration of Faith (Appendix A-B) b. Ritual Prayer (Appendices C-G) c. Obligatory Expenditure (H-I) d. Fasting Ramadan (J-M) e. Pilgrimage to Mecca (N-P) 4. Individual Activity: Using their notes, students will create a visual representation of the Five Pillars of Islam. 5. Pair Activity: Students will create a double bubble comparing and contrasting Islam with Christianity. (**You can substitute any other religion the students are familiar with or have been studying.**) Resources: www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/islam08.socst.world.glob.lppillars/the-five-pillars-of-islam/ http://www.thirteen.org/edonline/accessislam/lessonplan2.html http://www.discoverislam.co.uk/ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/teach/muslims/beliefs.html THE FIVE PILLARS OF ISLAM PILLAR DESCRIPTION/ NOTES PICTURE The Declaration of Faith Ash - Shahadah STATION 1: DECLARATION OF FAITH With your group, examine Appendices A-C and discuss the following questions. -

The Legalization of Theology in Islam and Judaism in the Thought of Al-Ghazali and Maimonides

UC Berkeley Berkeley Journal of Middle Eastern & Islamic Law Title Law as Faith, Faith as Law: The Legalization of Theology in Islam and Judaism in the Thought of Al-Ghazali and Maimonides Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7hm3k78p Journal Berkeley Journal of Middle Eastern & Islamic Law, 6(1) Author Pill, Shlomo C. Publication Date 2014-04-01 DOI 10.15779/Z38101S Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 1 BERKELEY J. OF MIDDLE EASTERN & ISLAMIC LAW 2014 LAW AS FAITH, FAITH AS LAW: THE LEGALIZATION OF THEOLOGY IN ISLAM AND JUDAISM IN THE THOUGHT OF AL-GHAZALI AND MAIMONIDES Shlomo C. Pill1 I. INTRODUCTION Legal systems tend to draw critical distinctions between members and nonmembers of the legal-political community. Typically, citizens, by virtue of shouldering the burden of legal obligations, enjoy more expansive legal rights and powers than noncitizens. While many modern legal regimes do offer significant human rights protections to non-citizens within their respective jurisdictions, even these liberal legal systems routinely discriminate between citizens and non- citizens with respect to rights, entitlements, obligations, and the capacity to act in legally significant ways. In light of these distinctions, it is not surprising that modern legal systems spend considerable effort delineating the differences between citizen and noncitizen, as well as the processes for obtaining or relinquishing citizenship. As nomocentric, or law-based faith traditions, Islam and Judaism also draw important distinctions between Muslims and non-Muslims, Jews and non- Jews. In Judaism, only Jews are required to abide by Jewish law, or halakha, and consequently only Jews may rightfully demand the entitlements that Jewish law duties create, while the justice owed by Jews to non-Jews is governed by a general rule of reciprocity. -

Islam and Politics in Tunisia

Islam and Politics in Tunisia How did the Islamist party Ennahda respond to the rise of Salafism in post-Arab Spring Tunisia and what are possible ex- planatory factors of this reaction? April 2014 Islam and Politics in a Changing Middle East Stéphane Lacroix Rebecca Koch Paris School of© International Affairs M.A. International Security Student ID: 100057683 [email protected] Words: 4,470 © The copyright of this paper remains the property of its author. No part of the content may be repreoduced, published, distributed, copied or stored for public use without written permission of the author. All authorisation requests should be sent to [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 3 2. Definitions and Theoretical Framework ............................................................... 4 3. Analysis: Ennahda and the Tunisian Salafi movements ...................................... 7 3.1 Ennahda ........................................................................................................................ 7 3.2 Salafism in Tunisia ....................................................................................................... 8 3.3 Reactions of Ennahda to Salafism ................................................................................ 8 4. Discussion ................................................................................................................ 11 5. Conclusion -

Faith Guides for Higher Education: a Guide to Islam

islam_cover.qxp 15/08/2007 15:21 Page 1 Faith Guides for Higher Education Islam A Guide to Islam Amjad Hussain and Kate El-Alami Faith Guides for Higher Education A Guide to Islam Amjad Hussain, Kate El-Alami Series editor: Gary R. Bunt Copy editor: Julie Closs Copyright © the Subject Centre for Philosophical and Religious Studies, 2005 (formerly PRS-LTSN) Picture permissions: Page 5: Qur’anic Calligraphy © Aftab Ahmad/Saudi Aramco World/PADIA. Page 7: The Hajj, Mecca © S.M. Amin/Saudi Aramco World/PADIA. Page 9: A stained-glass window by Simon Tretheway © Lydia Sharman Male/Saudi Aramco World/PADIA. Page 11: Illuminated Ottoman Qur’an, 17th century © Dick Doughty/Saudi Aramco World/PADIA. Page 12: Kaaba, Mecca © S.M. Amin/Saudi Aramco World/PADIA. Page 15: Shah Jehan Mosque, Woking © Tor Eigeland/Saudi Aramco World/PADIA. Page 16: Regent’s Park Mosque, London © Tor Eigeland/Saudi Aramco World/PADIA. Published by the Subject Centre for Philosophical and Religious Studies (formerly PRS-LTSN) Higher Education Academy School of Theology and Religious Studies University of Leeds LS2 9JT First Published November 2005 Reprinted July 2007 ISBN 0-9544524-5-3 All rights reserved. Except for quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, and for use in learning and teaching contexts in UK higher and further education, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of this publication and the other titles in the series, neither the publisher, series editor, nor authors are responsible for applications and uses of the information contained within. -

Inside the Jihadi Mind Understanding Ideology and Propaganda

Inside the Jihadi Mind Understanding Ideology and Propaganda EMMA EL-BADAWY MILO COMERFORD PETER WELBY 1 2 Contents Executive Summary 5 Policy Recommendations 9 Introduction 13 Framework for Analysis Values 23 Objectives 35 Conduct 45 Group Identity 53 Scripture and Scholarship How Jihadi Groups Use the Quran and Hadith 63 How Jihadi Groups Make Use of / Reject Scholarship 67 Appendices Methodology 70 Glossary 74 Acknowledgements 76 Note This report was first published in October 2015. The research was carried by the Centre on Religion & Geopolitics. The work of the Centre on Religion & Geopolitics is now carried out by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. 3 4 1.0 Executive Summary This report identifies what ideology is shared by ISIS, Jabhat al- Nusra, and al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninusla, as revealed in their propaganda, in order to inform effective counter-narratives. The ideology of global extremism can only be countered if it is first understood. This combination of theology and political objectives needs to be uprooted through rigorous scrutiny, and sustained intellectual confrontation. After the 9/11 attacks, Osama Bin Laden’s al- Qaeda had approximately 300 militants. ISIS alone has, at a low estimate, 31,000 fighters across Syria 55 and Iraq. Understanding how ideology has driven this Salafi-jihadism is a vital motivating force for extremist phenomenon is essential to containing and defeating violence, and therefore must be countered in order to violent extremism. curb the threat. But violent ideologies do not operate in a vacuum. AIM OF THE REPORT SUMMARY EXECUTIVE A fire requires oxygen to grow. -

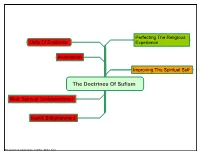

The Doctrines of Sufism

Perfecting The Religious Unity Of Existence Experience Annihilation Improving The Spiritual Self The Doctrines Of Sufism Wali: Spiritual Guide/sainthood Kashf: Enlightenment The doctrines of sufism.mmap • 3/4/2006 • Mindjet Team Emphasizes perception, maarifa leading to direct knowledge of Self and God, and Sufism uses the heart as its medium Emphasizes reason, ilm leading to understanding of God, uses the Aaql as The Context: (The Approaches To its medium, and subjects reason to Faith And Understanding) Kalam revelation Emphasizes reason, ilm leading to understanding of God, uses the Aaql as Philosophy its medium AL BAQARA Al Junayd Al Hallaj Annihilation By Examples Taqwa: Piety Sobriety The Goals Of The Spiritual Journey Paradox and biwelderment Intoxication QAAF The Consequence Of Annihilation Annihilation Abu Bakr (RAA): Incapacity to perceive is perception Perplexity Results from the negation in the first part of the Shahada (fana) AL HADEED And from the affirmation of the Living the Shahada subsistence in the second part of the Shahada: (Baqa) Be witness to the divine reality, and eliminate the egocentric self Living the Tawheed The Motivation For Annihilation Start as a stone Be shuttered by the divine light of the Self transformation divine reality you witness Emerge restructed as a jewel The Origins Of Annihilation AL RAHMAN Annihilation.mmap • 3/6/2006 • Mindjet Team Born and Raised in Baghdad (died in 910 or 198 H) His education focused on Fiqh and Hadith He studied under the Jurist Abu Thawr: An extraordinary jurist started as a Hanafii, then followed the Shafi school once al Imam Al Shafi came to Baghdad. -

Re the Five Pillars of Islam?

What are the Five Pillars of Islam? The Five Pillars of Islam are five duties that Muslims try to carry out. It helps them to feel like a part of the Muslim community. Each pillar has a different name; Shahada, Salah, Zakat, Sawm, and Hajj. Shahada – Pillar One This pillar is the main belief of all Muslim people and it is a declaration of their faith. The English words are: “There is no god except Allah, Muhammad is the messenger of Allah.” Muslims say this when they pray. Anyone who says these words and means it can become a Muslim. Salah – Pillar Two This pillar is prayer. Muslims pray five times a day and follow a special ritual to do so. First they must wash in symbolically clean water. All the prayers are said at the same time every day. Fajr – Morning, between dawn and sunrise. Zuhr – Mid-day or early afternoon. Asr – Late afternoon. Maghrib – Evening, around sunset. Isah – Night, before going to bed. Zakat – Pillar Three This pillar is about looking after other people. Each Muslim gives up a share of his wealth each year to provide for those less fortunate. The word zakat means to purify or cleanse. As a person gives away a share of their wealth they become cleansed from selfishness and greed. Sawm – Pillar Four This pillar is all about Ramadan. The ninth month of the Islam calendar is when Muhammad began receiving messages from God. For 30 days Muslims fast, they do not eat or drink during daylight hours. The fast is to remind them how difficult it is to be poor, hungry and thirsty. -

The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2021

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • B The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • i The Muslim 500: The World’s 500 Most Influential Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer Muslims, 2021 Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary ISBN: print: 978-9957-635-57-2 Managing Editor: Mr Aftab Ahmed e-book: 978-9957-635-56-5 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Jordan National Library Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour Deposit No: 2020/10/4503 Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, © 2020 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre Zeinab Asfour, Noora Chahine, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq PO BOX 950361 Typeset by: Haji M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN www.rissc.jo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanic, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily reflect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courte- sy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi MABDA • Contents • INTRODUCTION 1 Persons of the Year - 2021 5 A Selected Surveyof the Muslim World 7 COVID-19 Special Report: Covid-19 Comparing International Policy Effectiveness 25 THE HOUSE OF ISLAM 49 THE -

Sufi Cult in Mirpur

This is a repository copy of Ambiguous traditions and modern transformations of Islam: the waxing and waning of an ‘intoxicated’ Sufi cult in Mirpur. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/97211/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McLoughlin, S and Khan, M (2006) Ambiguous traditions and modern transformations of Islam: the waxing and waning of an ‘intoxicated’ Sufi cult in Mirpur. Contemporary South Asia, 15 (3). pp. 289-307. ISSN 0958-4935 https://doi.org/10.1080/09584930601098042 (c) 2006, Taylor and Francis. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Contemporary South Asia. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Seán McLoughlin & Muzamil Khan Ambiguous traditions and modern transformations of Islam: the waxing and waning of an S M Published in: Contemporary South Asia 15(3) September, 2006: 289307 Abstract: A I S A S shifting ambiguity and fixity of religious boundaries in colonial India, this article is an account of the cult of the Qadiriyya-Qalandariyya saints in the Mirpur district of Pakistan- administered Kashmir. -

Malay Undergraduates' Knowledge About the Kalima Shahadat

Malay Undergraduates’ Knowledge about the Kalima Shahadat Mohd Nizam Sahad & Fathullah Asni To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i5/4172 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i5/4172 Received: 18 April 2018, Revised: 07 May 2018, Accepted: 21 May 2018 Published Online: 14 June 2018 In-Text Citation: (Sahad & Asni, 2018) To Cite this Article: Sahad, M. N., & Asni, F. (2018). Malay Undergraduates’ Knowledge about the Kalima Shahadat. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(5), 708–719. Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 8, No. 5, May 2018, Pg. 708 - 719 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 8 , No. 5, May 2018, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2018 HRMARS Malay Undergraduates’ Knowledge about the Kalima Shahadat Mohd Nizam Sahad & Fathullah Asni School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Penang, Malaysia Email: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract The testimony of shahadat is a basic fundamental requirement which is a mandatory for the Muslims. -

Americas Real Enemy the Salafi Jihadi Movement

America’s Real Enemy THE SALAFI-JIHADI MOVEMENT Katherine Zimmerman JULY 2017 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE America’s Real Enemy THE SALAFI-JIHADI MOVEMENT Katherine Zimmerman JULY 2017 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE © 2017 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, 501(c)(3) educational organization and does not take institutional posi- tions on any issues. The views expressed here are those of the author(s). Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .....................................................................................................................................................................................3 Staying the Course for Far Too Long.....................................................................................................................................3 Why Now? ...................................................................................................................................................................................4 Understanding the Salafi-Jihadi Movement ............................................................................................................................6 Beyond al Qaeda and ISIS: The Salafi-Jihadi Base ..............................................................................................................6