Front Section-Pgs I-1.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology of the Nairobi Region, Kenya

% % % % % % % % %% %% %% %% %% %% %% % GEOLOGIC HISTORY % %% %% % % Legend %% %% %% %% %% %% %% % % % % % % HOLOCENE: %% % Pl-mv Pka %%% Sediments Mt Margaret U. Kerichwa Tuffs % % % % %% %% % Longonot (0.2 - 400 ka): trachyte stratovolcano and associated deposits. Materials exposed in this map % %% %% %% %% %% %% % section are comprised of the Longonot Ash Member (3.3 ka) and Lower Trachyte (5.6-3.3 ka). The % Pka' % % % % % % L. Kerichwa Tuff % % % % % % Alluvial fan Pleistocene: Calabrian % % % % % % % Geo% lo% gy of the Nairobi Region, Kenya % trachyte lavas were related to cone building, and the airfall tuffs were produced by summit crater formation % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Pna % % % % %% % (Clarke et al. 1990). % % % % % % Pl-tb % % Narok Agglomerate % % % % % Kedong Lake Sediments Tepesi Basalt % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % %% % % % 37.0 °E % % % % 36.5 °E % % % % For area to North see: Geology of the Kijabe Area, KGS Report 67 %% % % % Pnt %% % PLEISTOCENE: % % %% % % % Pl-kl %% % % Nairobi Trachyte % %% % -1.0 ° % % % % -1.0 ° Lacustrine Sediments % % % % % % % % Pleistocene: Gelasian % % % % % Kedong Valley Tuff (20-40 ka): trachytic ignimbrites and associated fall deposits created by caldera % 0 % 1800 % % ? % % % 0 0 % % % 0 % % % % % 0 % 0 8 % % % % % 4 % 4 Pkt % formation at Longonot. There are at least 5 ignimbrite units, each with a red-brown weathered top. In 1 % % % % 2 % 2 % % Kiambu Trachyte % Pl-lv % % % % % % % % % % %% % % Limuru Pantellerite % % % % some regions the pyroclastic glass and pumice has been -

National Drought Early Warning Bulletin June 2021

NATIONAL DROUGHT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY National Drought Early Warning Bulletin June 2021 1 Drought indicators Rainfall Performance The month of May 2021 marks the cessation of the Long- Rains over most parts of the country except for the western and Coastal regions according to Kenya Metrological Department. During the month of May 2021, most ASAL counties received over 70 percent of average rainfall except Wajir, Garissa, Kilifi, Lamu, Kwale, Taita Taveta and Tana River that received between 25-50 percent of average amounts of rainfall during the month of May as shown in Figure 1. Spatio-temporal rainfall distribution was generally uneven and poor across the ASAL counties. Figure 1 indicates rainfall performance during the month of May as Figure 1.May Rainfall Performance percentage of long term mean(LTM). Rainfall Forecast According to Kenya Metrological Department (KMD), several parts of the country will be generally dry and sunny during the month of June 2021. Counties in Northwestern Region including Turkana, West Pokot and Samburu are likely to be sunny and dry with occasional rainfall expected from the third week of the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be near the long-term average amounts for June. Counties in the Coastal strip including Tana River, Kilifi, Lamu and Kwale will likely receive occasional rainfall that is expected throughout the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be below the long-term average amounts for June. The Highlands East of the Rift Valley counties including Nyeri, Meru, Embu and Tharaka Nithi are expected to experience occasional cool and cloudy Figure 2.Rainfall forecast (overcast skies) conditions with occasional light morning rains/drizzles. -

Implementation Status of Kenya's Language in Education Policy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.4, No.23, 2013 Implementation Status of Kenya’s Language in Education Policy: A Case Study of Selected Primary Schools in Chuka Division, Meru South District, Kenya Nancy Wangui Mbaka * Christine Atieno Peter Mary Karuri Chuka University, P .O. Box 109-60400, Chuka, Kenya. *E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Language-in-education policies in many developing countries are constantly an issue of discussion in scholarly circles. This paper looks at the language-in- education policy in lower primary in Chuka Division, Meru-South District, Kenya. The paper evaluates the teachers’ awareness of the language policy and actual implementation in the classroom. It also analyses the problems that teachers experience in implementing the policy and gives the teacher’s recommendations in case the language policy were to be restructured. The paper establishes that teachers are aware of the policy but they do not always implement it in the classroom. The findings in this paper are of great benefit to all stakeholders in the ministry of education in Kenya and contribute to scholarly literature in the area of language planning and policy. Keywords: Language-in-Education Policy (LiEP), Policy Implementation, Language of Instruction (LOI), mother tongue (MT) 1. Introduction The important role that language plays in the acts of learning and teaching is recognized by education systems all over the world. -

Grazing Conditions in Kenya Masailand'

BURNING FLINT HILLS 269 LITERATURE CITED rainfall by prairie grasses, weeds, range sites to grazing treatment. ALDOUS,A. E. 1934. Effects of burn- and certain crop plants. Ecol. Ecol. Monog. 29: 171-186. ing on Kansas bluestem pastures. Monog. 10: 243-277. HOPKINS, H., F. W. ALBERTSONAND Kans. Agr. Expt. Sta. Bull. 38. 65 p. DYKSTERHUIS,E. J. 1949. Condition A. RIEGEL. 1948. Some effects of ANDERSON,KLING L. 1942. A com- and management of range land burning upon a prairie in west parison of line transects and per- based on quantitative ecology. J. central Kansas. Kans. Acad. Sci. manent quadrats in evaluating Range Manage. 2: 104-115. Trans. 51: 131-141. ELWELL, H. M., H. A. DANIEL AND composition and density of pasture LAUNCHBAUGH,J. L. 1964. Effects of F. A. FENTON. 1941. The effects of vegetation on the tall prairie grass early spring burning_ on yields of type. J. Amer. Sot. Agron. 34: 805- burning pasture and woodland native vegetation. J. Range Man- 822. vegetation. Okla. Agr. Expt. Sta. age. 17: 5-6. Bull. 247. 14 p. ANDERSON,KLINC L. AND C. L. FLY. HANKS, R. J. ANDKLING L. ANDERSON. MCMURPHY,W. E. AND KLING L. AN- 1955. Vegetation-soil relationships 1957. Pasture burning and moisture DERSON.1963. Burning bluestem in Flint Hills bluestem pastures. conservation. J. Soil and Water range-Forage yields. Kans. Acad. J. Range Manage. 8: 163-169. Conserv. 12: 228-229. Sci. Trans. 66: 49-51. BIEBER,G. L. ANDKLING L. ANDERSON. HENSEL,R. L. 1923. Effect of burning SMITH, E. F., K. L. -

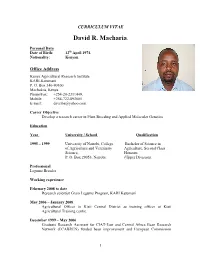

David R. Macharia

CURRICULUM VITAE David R. Macharia. Personal Data Date of Birth: 12th April 1974. Nationality: Kenyan Office Address Kenya Agricultural Research Institute KARI-Katumani P. O. Box 340-90100 Machakos, Kenya Phone/Fax: +254-20-2311449, Mobile: +254-722-893605 E-mail: [email protected] Career Objective Develop a research career in Plant Breeding and Applied Molecular Genetics Education Year University / School Qualification 1995 – 1999 University of Nairobi, College Bachelor of Science in of Agriculture and Veterinary Agriculture, Second Class Science, Honours P. O. Box 29053, Nairobi. (Upper Division). Professional Legume Breeder Working experience February 2008 to date Research scientist Grain Legume Program, KARI Katumani May 2006 – January 2008 Agricultural Officer in Kisii Central District as training officer at Kisii Agricultural Training centre. December 1999 – May 2006 Graduate Research Assistant for CIAT-East and Central Africa Bean Research Network (ECABREN) funded bean improvement and European Commission 1 Pigeonpea Improvement Projects at the University of Nairobi, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Science, Upper Kabete Campus Reports 1. Evaluation of Micronutrient-Rich Bean Varieties for Yield Potential in Semi- Arid Eastern Kenya. Annual Report. KARI-Katumani. 2. Effect of Rhizobia Inoculation and Fertilizer Use on Low Soil Fertility Tolerant Bean Lines in Semi-Arid Zone Annual Report. KARI-Katumani. 3. Evaluation of new red mottled bean cultivars for adaptability and yield potential in semi-arid Eastern Kenya Annual Report. KARI-Katumani. 4. Screening Bean Germplasm for tolerance to drought in drought-prone areas of Kenya, Tropical legume II Objective 4 (Breeding) Report. 5. Regeneration of Pigeonpea and Cowpea collections held at the National Genebank of Kenya Workshops/short training courses/seminars/conferences/meetings. -

I. General Overview Six Months After the Contested General Election in Kenya Led to Widespread Post Election Violence (PEV) An

UNITED NATIONS HUMANITARIAN UPDATE vol. 35 4 September – 10 September 2008 Office of the United Nations Humanitarian Coordinator in Kenya HIGHLIGHTS • A crisis situation is emerging in the Mandera districts due to consecutive failed rains; forecasts suggest that the situation may continue to deteriorate after the short rains. • The Kenyan Red Cross reported that there are 13,164 IDPs in 10 main IDP camps; the KRCS, WFP and an interagency assessment noted that there were at least 99,198 IDPs in 160 transit sites; the Government reported that 234,098 IDPs had returned to pre- displacement areas by 28 August. • UNICEF highlighted that over 95,000 children under the age of five and pregnant and breastfeeding women are malnourished. Of that number, 10,000 are severely malnourished. • A diarrhoea outbreak in Bungoma East, Bungoma West and Mount Elgon districts kills six while at least 171 seek treatment according to the Kenya Red Cross. The information contained in this report has been compiled by OCHA from information received from the field, from national and international humanitarian partners and from other official sources. It does not represent a position from the United Nations. This report is posted on: http://ochaonline.un.org/kenya I. General Overview Six months after the contested General Election in Kenya led to widespread post election violence (PEV) and the eventual formation of a Grand Coalition Government, a Gallup Poll was conducted to obtain popular opinions on past grievances, satisfaction with the current leadership and the way forward. Conducted between 19 June and 9 July across all provinces in Kenya, the Poll included a sample of 2,200 people. -

Understanding Urban Environment Problems in the Newly Urbanizing Areas of Kenya, a Case of Narok Town

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 8, ISSUE 06, JUNE 2019 ISSN 2277-8616 Understanding Urban Environment Problems In The Newly Urbanizing Areas Of Kenya, A Case Of Narok Town Mary Wambui Mwangi Abstract: Like many other countries in developing world, Kenya has been experiencing rapid urbanization. Although urbanization is associated with social and economic transformations, the trend is also associated with an increase in urban environment problems. The environment is considered as the gear to economic activities and the well fare of human beings. It is therefore important to understand the environmental consequences that comes with urbanization so as to safe guard the economy and the well fare of human beings living within and without the urban area. The study was conducted in Narok Town with a major focus of understanding urban environmental problems that the newly urbanizing areas in Kenya are facing. The study was conducted in five areas that make up Narok Town which include Lenana, Total, Majengo, London and the town center. The study was conducted using descriptive survey where questionnaires were administered to the respondents who were selected randomly to identify urban environmental problems in Narok Town. Observation and was also done in the study to identify urban environmental problems in Narok Town. Data that was gathered from the questionnaire was analyzed using SPSS Package version 20.0 and presented in forms of figurers and text. Data from observation was analyzed qualitatively and presented in form of text. The findings of the study indicate that Narok town is experiencing urban environmental problems which include development of slums, inadequate drainage systems. -

Assessment of the Alternative Es Approach for Encouraging Andonment of Female Genital Mutilation in Kenya

Assessment of the Alternative es Approach for Encouraging andonment of Female Genital Mutilation in Kenya J Population Council Jane Njeri Chege 4 Ian Askew Jennifer Liku ~frQnl\~!~ An Assessment of the Alternative Rites Approach for Encouraging Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation in Kenya FRONTIERS in Reproductive Health Jane Njeri Chege Ian Askew Jennifer Liku September 2001 An Assessment of the Alternative Rites Approach for Encouraging Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation in Kenya. This study was funded by the UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (USAID) under the terms of Cooperative Agreement number HRN-A-00-98-00012-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of USAID. DEDICATION The late Leah Muuya (died December 2000) has left an invaluable imprint in the struggle to free young girls from the practice of Female Genital Mutilation. As Maendeleo Ya Wanawake Organisation’s (MYWO) Programme Officer for Harmful Traditional Practices, Leah spearheaded activities related to the alternative rites of passage. Her enthusiasm and willingness to work with various communities in seeking to influence change of attitudes and behaviour made a great impact in the success of the programme. As a tribute to her, we dedicate the work contained in this report to her to commemorate her contribution to the eradication of this practice, on behalf of all the young girls she enabled to find hope despite the clutch of culture. An Assessment of the Alternative Rites Approach for Encouraging Abandonment of FGM in Kenya SUMMARY Maendeleo Ya Wanawake (MYWO), with technical assistance from the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), has been implementing an Alternative Rite of passage programme as part of its efforts to eradicate the practice of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) in five districts in Kenya. -

Policy Brief. Engaging Young People in Narok County, Kenya

POPULATION REFERENCE Policy Brief BUREAU OCTOBER 2018 UPDATED APRIL 2021 ENGAGING YOUNG PEOPLE IN NAROK COUNTY IN DECISIONMAKING IMPROVES YOUTH-FRIENDLY FAMILY PLANNING SERVICES Young people’s well-being shapes the health, development, and economic growth of the larger BOX 1 community. This relationship is particularly true National Policies That in Narok County, Kenya, where more than half of 16.7 Support Youth-Friendly Median age of first the population is under age 15. As Narok’s young sexual intercourse for people transition to adulthood, investments in Family Planning Services women ages 20 to 49 in their reproductive health can lay the groundwork Narok County. Kenya has an inclusive and supportive policy for good health and greater opportunities for them environment for the provision of sexual and and for the county. Including young people in the reproductive health services to both youth and decisionmaking surrounding those investments can adolescents. help ensure health programs’ success. • National Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Policy, 2015. The Kenya Health Sector Strategic Plan, for instance, • National Guidelines for the Provision of underscores the government’s commitment to Adolescent and Youth Friendly Services, 2016. 38% achieving UHC as a national priority that ensures Share of married women • National Family Planning Costed Implementation ages 15 to 49 in Narok “that all individuals and communities in Kenya have Plan 2017-2020. currently using a modern access to good-quality essential health services • National Adolescent Sexual Reproductive Health method of contraception. without suffering from financial hardship.” Policy Implementation Framework 2017-2021. Given Kenya’s national policy environment, counties have a responsibility to translate national policies into programs and services that meet Health Management Team (CHMT) can seize a young people’s needs. -

National Drought Early Warning Bulletin July 2021

NATIONAL DROUGHT MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY National Drought Early Warning Bulletin July 2021 1 Drought indicators Rainfall Performance The month of June 2021 marked the beginning of the cold season with several parts of ASAL counties remaining dry. According to metrological department, most of ASAL counties received less than 50 percent of average rainfall with most parts of Marsabit, Wajir, Garissa, Isiolo, Kajiado, Tana River and Turkana receiving less than 25 percent of average amounts of rainfall during the month of June as shown in Figure 1a.The coastal strip received over 75 percent of average amounts. Spatio-temporal rainfall distribution was generally uneven and poor across the ASAL counties. Figure 1a indicates rainfall Figure 1 a.June Rainfall Performance performance during the month of May as percentage of long term mean (LTM). Rainfall Forecast According to Kenya Meteorological Department (KMD), several parts of the country will be generally dry and sunny during the month of July 2021.Counties in Northwestern Region including Turkana, West Pokot and Samburu are likely to receive occasional rainfall during the beginning of the month and near average rainfall towards the end of the month. The expected total rainfall is likely to be near to above the long term average for July. Counties in the Coastal strip including Tana River, Kilifi, Lamu and Kwale will likely receive occasional rainfall. The expected total rainfall is likely to be near the long-term average amounts for July. The Highlands East of the Rift Valley counties including Nyeri, Meru, Embu and Tharaka Nithi are expected to experience occasional Figure 1b.Rainfall forecast cool and cloudy (overcast skies) conditions with occasional rains/drizzles while the Northeastern Kenya counties including Mandera, Marsabit, Wajir, Garissa and Isiolo and Southeastern lowlands counties including Machakos, Makueni, Kitui, Taita Taveta and parts of Kajiado are likely to remain generally sunny and dry. -

Press Statement on Covid-19 2Nd August, 2021

NATIONAL EMERGENCY RESPONSE COMMITTEE ON CORONAVIRUS UPDATE ON COVID-19 IN THE COUNTRY AND RESPONSE MEASURES, AS AT AUGUST 2, 2021 DAY: 503 BRIEF NO: 495 PRESS STATEMENT Today 591 people have tested positive for the disease, from a sample size of 4,737 tested in the last 24 hours. The positivity rate is now 12.5%. From the cases 575 are Kenyans while 16 are foreigners. 316 males while 275 are females. The youngest is a 10-month-old baby while the oldest is 87 years. Total confirmed positive cases are now 204,271 and cumulative tests so far conducted are 2,142,309. 1 In terms of County distribution; Nairobi 422, Mombasa 34, Kiambu 19, Uasin Gishu 17, Garissa 14, Murang’a 10, Kirinyaga 9, Nyeri 9, Busia 7, Narok 6, Kajiado 4, Laikipia 4, Machakos 4, Kakamega 4, Baringo 3, Mandera 3, Embu 3, Nakuru 3, Nyandarua 3, Siaya 2, Kisii 2, Homa Bay 1, Kericho 1, Kilifi 1, Kitui 1, Meru 1, Nandi 1, Elgeyo Marakwet 1, Trans Nzoia 1 and West Pokot 1. In terms of Sub County distribution; the 422 cases in Nairobi are from Westlands (41), Dagoretti North (36), Kibra (32), Embakasi Central, Embakasi East, Langata and Makadara (26) cases each, Mathare (25), Embakasi West and Starehe (24) cases each, Kamukunji (23), Embakasi South and Kasarani (22) cases each, Roysambu (21), Ruaraka (19), Embakasi North (15), Dagoretti South (14). In Mombasa the 34 cases are from Jomvu (20), Mvita (7), Likoni (4), Changamwe, Kisauni and Nyali (1) case each. In Kiambu the 19 cases are from Kiambu Town (6), Kikuyu (5), Kiambaa (4), Ruiru (3), Kabete (1). -

Akiwumi.Rift Valley.Pdf

CHAPTER ONE TRIBAL CLASHES IN THE RIFT VALLEY PROVINCE Tribal clashes in the Rift Valley Province started on 29th October, 1991, at a farm known as Miteitei, situated in the heart of Tinderet Division, in Nandi District, pitting the Nandi, a Kalenjin tribe, against the Kikuyu, the Kamba, the Luhya, the Kisii, and the Luo. The clashes quickly spread to other farms in the area, among them, Owiro, farm which was wholly occupied by the Luo; and into Kipkelion Division of Kericho District, which had a multi-ethnic composition of people, among them the Kalenjin, the Kisii and the Kikuyu. Later in early 1992, the clashes spread to Molo, Olenguruone, Londiani, and other parts of Kericho, Trans Nzoia, Uasin Gishu and many other parts of the Rift Valley Province. In 1993, the clashes spread to Enoosupukia, Naivasha and parts of Narok, and the Trans Mara Districts which together then formed the greater Narok before the Trans Mara District was hived out of it, and to Gucha District in Nyanza Province. In these areas, the Kipsigis and the Maasai, were pitted against the Kikuyu, the Kisii, the Kamba and the Luhya, among other tribes. The clashes revived in Laikipia and Njoro in 1998, pitting the Samburu and the Pokot against the Kikuyu in Laikipia, and the Kalenjin mainly against the Kikuyu in Njoro. In each clash area, non-Kalenjin or non-Maasai, as the case may be, were suddenly attacked, their houses set on fire, their properties looted and in certain instances, some of them were either killed or severely injured with traditional weapons like bows and arrows, spears, pangas, swords and clubs.