Decoupling Employment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non State Employer Group Employee Guidebooks

STATE EMPLOYEE HEALTH PLAN NON-STATE GROUP EMPLOYEES BENEFIT GUIDEBOOK PLAN YEAR 2020 - 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS VENDOR CONTACT INFORMATION .............................................................................................................. 2 MEMBERSHIP ADMINISTRATION PORTAL .................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 4 GENERAL DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................................................ 5 EMPLOYEE ELIGIBILITY ................................................................................................................................ 7 OTHER ELIGIBLE INDIVIDUALS UNDER THE SEHP .................................................................................... 9 ANNUAL OPEN ENROLLMENT PERIOD ...................................................................................................... 16 MID-YEAR ENROLLMENT CHANGES .......................................................................................................... 17 LEAVE WITHOUT PAY AND RETURN FROM LEAVE WITHOUT PAY …………………………………………22 FAMILY MEDICAL LEAVE ACT(FMLA), FURLOUGHS AND LAYOFFS ……………………………………….23 HEALTH INSURANCE PORTABILITY AND ACCOUNTABILITY ACT (HIPAA) ............................................ 24 FLEXIBLE SPENDING ACCOUNT PROGRAM - 2021 .................................................................................. -

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery Siobhán McGrath Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science, New School University Economic Development & Global Governance and Independent Study: William Milberg Spring 2005 1. Introduction It is widely accepted that capitalism is characterized by “free” wage labor. But what is “free wage labor”? According to Marx a “free” laborer is “free in the double sense, that as a free man he can dispose of his labour power as his own commodity, and that on the other hand he has no other commodity for sale” – thus obliging the laborer to sell this labor power to an employer, who possesses the means of production. Yet, instances of “unfree labor” – where the worker cannot even “dispose of his labor power as his own commodity1” – abound under capitalism. The question posed by this paper is why. What factors can account for the existence of unfree labor? What role does it play in an economy? Why does it exist in certain forms? In terms of the broadest answers to the question of why unfree labor exists under capitalism, there appear to be various potential hypotheses. ¾ Unfree labor may be theorized as a “pre-capitalist” form of labor that has lingered on, a “vestige” of a formerly dominant mode of production. Similarly, it may be viewed as a “non-capitalist” form of labor that can come into existence under capitalism, but can never become the central form of labor. ¾ An alternate explanation of the relationship between unfree labor and capitalism is that it is part of a process of primary accumulation. -

The Bullying of Teachers Is Slowly Entering the National Spotlight. How Will Your School Respond?

UNDER ATTACK The bullying of teachers is slowly entering the national spotlight. How will your school respond? BY ADRIENNE VAN DER VALK ON NOVEMBER !, "#!$, Teaching Tolerance (TT) posted a blog by an anonymous contributor titled “Teachers Can Be Bullied Too.” The author describes being screamed at by her department head in front of colleagues and kids and having her employment repeatedly threatened. She also tells of the depres- sion and anxiety that plagued her fol- lowing each incident. To be honest, we debated posting it. “Was this really a TT issue?” we asked ourselves. Would our readers care about the misfortune of one teacher? How common was this experience anyway? The answer became apparent the next day when the comments section exploded. A popular TT blog might elicit a dozen or so total comments; readers of this blog left dozens upon dozens of long, personal comments every day—and they contin- ued to do so. “It happened to me,” “It’s !"!TEACHING TOLERANCE ILLUSTRATION BY BYRON EGGENSCHWILER happening to me,” “It’s happening in my for the Prevention of Teacher Abuse repeatedly videotaping the target’s class department. I don’t know how to stop it.” (NAPTA). Based on over a decade of without explanation and suspending the This outpouring was a surprise, but it work supporting bullied teachers, she target for insubordination if she attempts shouldn’t have been. A quick Web search asserts that the motives behind teacher to report the situation. revealed that educators report being abuse fall into two camps. Another strong theme among work- bullied at higher rates than profession- “[Some people] are doing it because place bullying experts is the acute need als in almost any other field. -

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Julie M. Whittaker Specialist in Income Security Katelin P. Isaacs Analyst in Income Security March 28, 2012 The House Ways and Means Committee is making available this version of this Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, with the cover date shown, for inclusion in its 2012 Green Book website. CRS works exclusively for the United States Congress, providing policy and legal analysis to Committees and Members of both the House and Senate, regardless of party affiliation. Congressional Research Service R42444 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Summary The temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08) program may provide additional federal unemployment insurance benefits to eligible individuals who have exhausted all available benefits from their state Unemployment Compensation (UC) programs. Congress created the EUC08 program in 2008 and has amended the original, authorizing law (P.L. 110-252) 10 times. The most recent extension of EUC08 in P.L. 112-96, the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012, authorizes EUC08 benefits through the end of calendar year 2012. P.L. 112- 96 also alters the structure and potential availability of EUC08 benefits in states. Under P.L. 112- 96, the potential duration of EUC08 benefits available to eligible individuals depends on state unemployment rates as well as the calendar date. The P.L. 112-96 extension of the EUC08 program does not allow any individual to receive more than 99 weeks of total unemployment insurance (i.e., total weeks of benefits from the three currently authorized programs: regular UC plus EUC08 plus EB). -

Employment Application 31555 W

EMPLOYMENT APPLICATION 31555 W. 11 Mile Road Farmington Hills, MI 48336-1165 Attention: Human Resources www.fhgov.com Applicants for all positions are considered without regard to religion, race, color, national origin, age, gender, height, weight, disability, marital or veteran status or any other legally protected status. Position applied for: Date: Name: Last First Middle Address: Street City State Zip Code Telephone: Home Cell e-mail address Have you ever filed an application with the City before? Yes No If yes, give approximate date. Have you been employed with the City before? Yes No If yes, give dates. Are you available to work: Full-time Part-time Temporary # of hours per week: May your present employer be contacted? Yes No Are you 18 years of age or older? Yes No Can you provide proof of eligibility for employment in the USA? Yes No (Proof of citizenship or immigration status will be required upon employment.) On what date are you available for work? Do you have a valid driver’s license? Yes No License Number: State: List the names of any relatives who are City Council Members, appointees or employees of the City and your relationship to them. Have you been convicted of a misdemeanor or felony? Yes No Do you have felony charges pending against you? Yes No If you answered yes to either of the above questions, please provide dates, places, charges and disposition of all convictions. THE CITY IS AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY EMPLOYER Education and Training Are you a High School Graduate? Yes No Schools attended Location Courses or Dates of # of Grade Degree or Certificate (State) Credits Average beyond High Major Studies Attendance Completed Type Year School Describe any specialized training, apprenticeships, skills, languages, extracurricular activities or honors. -

Unemployment, Health Insurance, and the COVID-19 Recession

Support for this research was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Unemployment, Health Insurance, and the COVID-19 Recession Anuj Gangopadhyaya and Bowen Garrett Timely Analysis of Immediate Health Policy Issues APRIL 2020 Introduction for many given their reduced income. and the economy, we examine the The sharp reduction in US economic Those losing their jobs and employer- kinds of health insurance unemployed activity associated with public health sponsored health insurance (ESI) would workers have and how coverage efforts to slow the spread of the be able to purchase individual health patterns have shifted over time under the COVID-19 virus is likely to result in insurance (single or family coverage) ACA. Workers who lose their jobs may millions of Americans losing their jobs through the marketplaces established by search for employment or might leave and livelihoods, at least temporarily. the Affordable Care Act (ACA), possibly the labor market entirely. After a while, The global economy is likely already in with access to subsidies (tax credits) unemployed workers searching for jobs recession.1 Economic forecasts suggest depending on their family income. Under may become discouraged and they could that job losses in the second quarter of current law, they must enroll in nongroup also leave the labor market. We compare 2020 could exceed those experienced coverage within 60 days of the qualifying health insurance coverage for working- during the Great Recession.2 Whereas event (e.g., job, income, or coverage age, unemployed adults with that for the monthly U.S. -

The Erosion of Retiree Health Benefits and Retirement Behavior

The number of companies The Erosion of Retiree Health Benefits offering health benefits to early retirees is declining, and Retirement Behavior: Implications although reductions in the percentage of early retirees for the Disability Insurance Program covered by health insurance have been only slight to date. by Paul Fronstin* In general, workers who will be covered by health insur Summary year gap between eligibility for DI and ance are more likely than Medicare. In fact, persons with suffi The effects of retiree health insurance other workers to retire before cient means to retire early could use the the age of 65, when they be on the decision to retire have not been income from Disability Insurance to buy come eligible for Medicare. examined until recently. It is an area of COBRA coverage during the first 2 What effect that will have on increasing significance because of rising years of DI coverage. claims under the Disability health care costs for retirees, the uncer Determining the effect of the erosion Insurance program is not yet tain future of Medicare, and increased of retiree health benefits on DI must clear. life expectancy. In general, studies account properly for the role of other Acknowledgments: An earlier suggest that individual retirement deci factors that affect DI eligibility and version of this paper was sions are strongly responsive to the participation. The financial incentives of presented at the symposium on availability of retiree health insurance. Social Security, pension plans, retire Disability, Health, and Retire- Early retiree benefits and retirement ment Age: Challenges for Social ment savings programs, health status, the behavior are also important because they Security Policy, cosponsored by availability of health insurance, and may affect the Social Security Disability the Social Security Administra- other factors influencing retirement tion and the National Academy of Insurance (DI) program. -

The Effect of Health Insurance on Retirement

BRIGITTE C. MADRIAN Harvard University The Effect of Health Insurance on Retirement FOR DECADES health insurancein the United States has been provided to most nonelderlyAmericans through their own or a family member's employment. This system of employment-basedhealth insurance has evolved largelybecause of the substantialcost advantagesthat employ- ers enjoy in supplyinghealth insurance. By pooling largenumbers of in- dividuals, employers face significantlylower administrativeexpenses thando individuals.In addition,employer expenditures on healthinsur- ance are tax deductible,but individualexpenditures are generallynot. I Despite these cost advantages, there is widespread dissatisfaction with this system of employment-basedhealth insurance. Many people are excluded because not all employersprovide health insurance and not all individualslive in households in which someone is employed. An es- timated 36 million Americans were uninsured in 1990.2 Even among those fortunate enough to have employer-providedhealth insurance, there is mountingconcern that it discourages individuals with preex- isting conditionsfrom changingjobs and, for those who do changejobs, it often means findinga new doctor because insuranceplans vary from firmto firm. I wish to thankGary Burtless, David Cutler, Jon Gruber,Jerry Hausman, Jim Poterba, andAndrew Samwick for theircomments and suggestions. 1. Undercurrent tax law, there are two circumstancesin which individualsmay de- duct theirexpenditures on healthinsurance: (1) those who are self-employedand who do not have -

The Effect of Overtime Regulations on Employment

RONALD L. OAXACA University of Arizona, USA, CEPS/INSTEAD, Luxembourg, PRESAGE, France, and IZA, Germany The effect of overtime regulations on employment There is no evidence that being strict with overtime hours and pay boosts employment—it could even lower it Keywords: overtime, wages, labor demand, employment ELEVATOR PITCH A shorter standard workweek boosts incentives Regulation of standard workweek hours and overtime for multiple job holding and undermines work sharing hours and pay can protect workers who might otherwise be Standard workweek (hours) Percent moonlighting required to work more than they would like to at the going rate. By discouraging the use of overtime, such regulation 48 44 can increase the standard hourly wage of some workers 40 and encourage work sharing that increases employment, with particular advantages for female workers. However, regulation of overtime raises employment costs, setting in motion economic forces that can limit, neutralize, or even reduce employment. And increasing the coverage of 7.6 overtime pay regulations has little effect on the share of 4.8 4.3 workers who work overtime or on weekly overtime hours per worker. Source: Based on data in [1]. KEY FINDINGS Pros Cons Regulation of standard workweek hours and Curbing overtime reduces employment of both overtime hours and pay can protect workers who skilled and unskilled workers. might otherwise be required to work more than they Overtime workers tend to be more skilled, so would like to at the going rate. unemployed and other workers are not satisfactory Shortening the legal standard workweek can substitutes for overtime workers. potentially raise employment, especially among Shortening the legal standard workweek increases women. -

The Effect of an Employer Health Insurance Mandate On

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES The Effect of an Employer Health Insurance Mandate on Health Insurance Coverage and the Demand for Labor: Evidence from Hawaii Thomas C. Buchmueller University of Michigan John DiNardo University of Michigan Robert G. Valletta Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco April 2011 Working Paper 2009-08 http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/papers/2009/wp09-08bk.pdf The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The Effect of an Employer Health Insurance Mandate on Health Insurance Coverage and the Demand for Labor: Evidence from Hawaii Thomas C. Buchmueller Stephen M. Ross School of Business University of Michigan 701 Tappan Street Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Email: [email protected] John DiNardo Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy and Department of Economics University of Michigan 735 S. State St. Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Email: [email protected] Robert G. Valletta Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco 101 Market Street San Francisco, CA 94105 email: [email protected] April 2011 JEL Codes: J32, I18, J23 Keywords: health insurance, employment, hours, wages The authors thank Meryl Motika, Jaclyn Hodges, Monica Deza, Abigail Urtz, Aisling Cleary, and Katherine Kuang for excellent research assistance, Jennifer Diesman of HMSA for providing data, and Gary Hamada, Tom Paul, and Jerry Russo for providing essential background on the PHCA. Thanks also go to Nate Anderson, Julia Lane, Reagan Baughman, and seminar participants at Michigan State University, the University of Hawaii, Cornell University, and the University of Illinois (Chicago and Urbana-Champaign) for helpful comments and suggestions on earlier versions of the manuscript. -

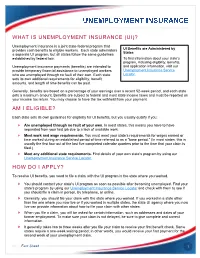

What Is Unemployment Insurance (Ui)? Am I Eligible? How Do I Apply?

WHAT IS UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE (UI)? Unemployment Insurance is a joint state-federal program that provides cash benefits to eligible workers. Each state administers UI Benefits are Administered by States a separate UI program, but all states follow the same guidelines established by federal law. To find information about your state’s program, including eligibility, benefits, Unemployment insurance payments (benefits) are intended to and application information, visit our provide temporary financial assistance to unemployed workers Unemployment Insurance Service who are unemployed through no fault of their own. Each state Locator. sets its own additional requirements for eligibility, benefit amounts, and length of time benefits can be paid. Generally, benefits are based on a percentage of your earnings over a recent 52-week period, and each state sets a maximum amount. Benefits are subject to federal and most state income taxes and must be reported on your income tax return. You may choose to have the tax withheld from your payment. AM I ELIGIBLE? Each state sets its own guidelines for eligibility for UI benefits, but you usually qualify if you: Are unemployed through no fault of your own. In most states, this means you have to have separated from your last job due to a lack of available work. Meet work and wage requirements. You must meet your state’s requirements for wages earned or time worked during an established period of time referred to as a "base period." (In most states, this is usually the first four out of the last five completed calendar quarters prior to the time that your claim is filed.) Meet any additional state requirements. -

Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees

Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees A Report to the President and the Congress of the United States by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board September 2010 THE CHAIRMAN U.S. MERIT SYSTEMS PROTECTION BOARD 1615 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20419-0001 September 2010 The President President of the Senate Speaker of the House of Representatives Dear Sirs and Madam: In accordance with the requirements of 5 U.S.C. § 1204(a)(3), it is my honor to submit this U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board report, Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees. The purpose of this report is to describe the requirements for a Federal employee’s disclosure of wrongdoing to be legally protected as whistleblowing under current statutes and case law. To qualify as a protected whistleblower, a Federal employee or applicant for employment must disclose: a violation of any law, rule, or regulation; gross mismanagement; a gross waste of funds; an abuse of authority; or a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety. However, this disclosure alone is not enough to obtain protection under the law. The individual also must: avoid using normal channels if the disclosure is in the course of the employee’s duties; make the report to someone other than the wrongdoer; and suffer a personnel action, the agency’s failure to take a personnel action, or the threat to take or not take a personnel action. Lastly, the employee must seek redress through the proper channels before filing an appeal with the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (“MSPB”). A potential whistleblower’s failure to meet even one of these criteria will deprive the MSPB of jurisdiction, and render us unable to provide any redress in the absence of a different (non-whistleblowing) appeal right.