The Effect of Overtime Regulations on Employment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Pay Gaps

Equality and Human Rights Commission Briefing paper 2 Gender pay gaps David Perfect Gender pay gaps David Perfect, Equality and Human Rights Commission © Equality and Human Rights Commission 2011 First published Spring 2011 ISBN 978 1 84206 351 4 Equality and Human Rights Commission Research The Equality and Human Rights Commission publishes research carried out for the Commission by commissioned researchers and by the Research Team. The views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent the views of the Commission. The Commission is publishing the report as a contribution to discussion and debate. Please contact the Research Team for further information about other Commission research reports, or visit our website: Research Team Equality and Human Rights Commission Arndale House The Arndale Centre Manchester M4 3AQ Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0161 829 8500 Website: www.equalityhumanrights.com You can download a copy of this report as a PDF from our website: http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/ If you require this publication in an alternative format, please contact the Communications Team to discuss your needs at: [email protected] Key findings Men working full-time continue to have higher average (mean) hourly, weekly and annual earnings than women. Across the United Kingdom, the mean full-time gender pay gap (the difference in percentage terms between the average earnings of women and men working full-time) in 2010 was 15.5 per cent for hourly earnings excluding overtime and 21.5 per cent for gross weekly earnings. The gap was wider in weekly than hourly earnings, since men tend to work longer weekly hours than women and are also more likely to receive additional payments, such as overtime. -

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery Siobhán McGrath Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science, New School University Economic Development & Global Governance and Independent Study: William Milberg Spring 2005 1. Introduction It is widely accepted that capitalism is characterized by “free” wage labor. But what is “free wage labor”? According to Marx a “free” laborer is “free in the double sense, that as a free man he can dispose of his labour power as his own commodity, and that on the other hand he has no other commodity for sale” – thus obliging the laborer to sell this labor power to an employer, who possesses the means of production. Yet, instances of “unfree labor” – where the worker cannot even “dispose of his labor power as his own commodity1” – abound under capitalism. The question posed by this paper is why. What factors can account for the existence of unfree labor? What role does it play in an economy? Why does it exist in certain forms? In terms of the broadest answers to the question of why unfree labor exists under capitalism, there appear to be various potential hypotheses. ¾ Unfree labor may be theorized as a “pre-capitalist” form of labor that has lingered on, a “vestige” of a formerly dominant mode of production. Similarly, it may be viewed as a “non-capitalist” form of labor that can come into existence under capitalism, but can never become the central form of labor. ¾ An alternate explanation of the relationship between unfree labor and capitalism is that it is part of a process of primary accumulation. -

The Bullying of Teachers Is Slowly Entering the National Spotlight. How Will Your School Respond?

UNDER ATTACK The bullying of teachers is slowly entering the national spotlight. How will your school respond? BY ADRIENNE VAN DER VALK ON NOVEMBER !, "#!$, Teaching Tolerance (TT) posted a blog by an anonymous contributor titled “Teachers Can Be Bullied Too.” The author describes being screamed at by her department head in front of colleagues and kids and having her employment repeatedly threatened. She also tells of the depres- sion and anxiety that plagued her fol- lowing each incident. To be honest, we debated posting it. “Was this really a TT issue?” we asked ourselves. Would our readers care about the misfortune of one teacher? How common was this experience anyway? The answer became apparent the next day when the comments section exploded. A popular TT blog might elicit a dozen or so total comments; readers of this blog left dozens upon dozens of long, personal comments every day—and they contin- ued to do so. “It happened to me,” “It’s !"!TEACHING TOLERANCE ILLUSTRATION BY BYRON EGGENSCHWILER happening to me,” “It’s happening in my for the Prevention of Teacher Abuse repeatedly videotaping the target’s class department. I don’t know how to stop it.” (NAPTA). Based on over a decade of without explanation and suspending the This outpouring was a surprise, but it work supporting bullied teachers, she target for insubordination if she attempts shouldn’t have been. A quick Web search asserts that the motives behind teacher to report the situation. revealed that educators report being abuse fall into two camps. Another strong theme among work- bullied at higher rates than profession- “[Some people] are doing it because place bullying experts is the acute need als in almost any other field. -

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Julie M. Whittaker Specialist in Income Security Katelin P. Isaacs Analyst in Income Security March 28, 2012 The House Ways and Means Committee is making available this version of this Congressional Research Service (CRS) report, with the cover date shown, for inclusion in its 2012 Green Book website. CRS works exclusively for the United States Congress, providing policy and legal analysis to Committees and Members of both the House and Senate, regardless of party affiliation. Congressional Research Service R42444 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08): Current Status of Benefits Summary The temporary Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08) program may provide additional federal unemployment insurance benefits to eligible individuals who have exhausted all available benefits from their state Unemployment Compensation (UC) programs. Congress created the EUC08 program in 2008 and has amended the original, authorizing law (P.L. 110-252) 10 times. The most recent extension of EUC08 in P.L. 112-96, the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act of 2012, authorizes EUC08 benefits through the end of calendar year 2012. P.L. 112- 96 also alters the structure and potential availability of EUC08 benefits in states. Under P.L. 112- 96, the potential duration of EUC08 benefits available to eligible individuals depends on state unemployment rates as well as the calendar date. The P.L. 112-96 extension of the EUC08 program does not allow any individual to receive more than 99 weeks of total unemployment insurance (i.e., total weeks of benefits from the three currently authorized programs: regular UC plus EUC08 plus EB). -

Employment Application 31555 W

EMPLOYMENT APPLICATION 31555 W. 11 Mile Road Farmington Hills, MI 48336-1165 Attention: Human Resources www.fhgov.com Applicants for all positions are considered without regard to religion, race, color, national origin, age, gender, height, weight, disability, marital or veteran status or any other legally protected status. Position applied for: Date: Name: Last First Middle Address: Street City State Zip Code Telephone: Home Cell e-mail address Have you ever filed an application with the City before? Yes No If yes, give approximate date. Have you been employed with the City before? Yes No If yes, give dates. Are you available to work: Full-time Part-time Temporary # of hours per week: May your present employer be contacted? Yes No Are you 18 years of age or older? Yes No Can you provide proof of eligibility for employment in the USA? Yes No (Proof of citizenship or immigration status will be required upon employment.) On what date are you available for work? Do you have a valid driver’s license? Yes No License Number: State: List the names of any relatives who are City Council Members, appointees or employees of the City and your relationship to them. Have you been convicted of a misdemeanor or felony? Yes No Do you have felony charges pending against you? Yes No If you answered yes to either of the above questions, please provide dates, places, charges and disposition of all convictions. THE CITY IS AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY EMPLOYER Education and Training Are you a High School Graduate? Yes No Schools attended Location Courses or Dates of # of Grade Degree or Certificate (State) Credits Average beyond High Major Studies Attendance Completed Type Year School Describe any specialized training, apprenticeships, skills, languages, extracurricular activities or honors. -

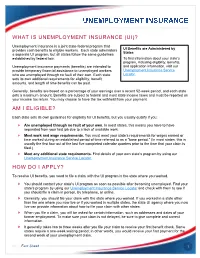

What Is Unemployment Insurance (Ui)? Am I Eligible? How Do I Apply?

WHAT IS UNEMPLOYMENT INSURANCE (UI)? Unemployment Insurance is a joint state-federal program that provides cash benefits to eligible workers. Each state administers UI Benefits are Administered by States a separate UI program, but all states follow the same guidelines established by federal law. To find information about your state’s program, including eligibility, benefits, Unemployment insurance payments (benefits) are intended to and application information, visit our provide temporary financial assistance to unemployed workers Unemployment Insurance Service who are unemployed through no fault of their own. Each state Locator. sets its own additional requirements for eligibility, benefit amounts, and length of time benefits can be paid. Generally, benefits are based on a percentage of your earnings over a recent 52-week period, and each state sets a maximum amount. Benefits are subject to federal and most state income taxes and must be reported on your income tax return. You may choose to have the tax withheld from your payment. AM I ELIGIBLE? Each state sets its own guidelines for eligibility for UI benefits, but you usually qualify if you: Are unemployed through no fault of your own. In most states, this means you have to have separated from your last job due to a lack of available work. Meet work and wage requirements. You must meet your state’s requirements for wages earned or time worked during an established period of time referred to as a "base period." (In most states, this is usually the first four out of the last five completed calendar quarters prior to the time that your claim is filed.) Meet any additional state requirements. -

Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees

Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees A Report to the President and the Congress of the United States by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board September 2010 THE CHAIRMAN U.S. MERIT SYSTEMS PROTECTION BOARD 1615 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20419-0001 September 2010 The President President of the Senate Speaker of the House of Representatives Dear Sirs and Madam: In accordance with the requirements of 5 U.S.C. § 1204(a)(3), it is my honor to submit this U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board report, Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees. The purpose of this report is to describe the requirements for a Federal employee’s disclosure of wrongdoing to be legally protected as whistleblowing under current statutes and case law. To qualify as a protected whistleblower, a Federal employee or applicant for employment must disclose: a violation of any law, rule, or regulation; gross mismanagement; a gross waste of funds; an abuse of authority; or a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety. However, this disclosure alone is not enough to obtain protection under the law. The individual also must: avoid using normal channels if the disclosure is in the course of the employee’s duties; make the report to someone other than the wrongdoer; and suffer a personnel action, the agency’s failure to take a personnel action, or the threat to take or not take a personnel action. Lastly, the employee must seek redress through the proper channels before filing an appeal with the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (“MSPB”). A potential whistleblower’s failure to meet even one of these criteria will deprive the MSPB of jurisdiction, and render us unable to provide any redress in the absence of a different (non-whistleblowing) appeal right. -

BP Labour Rights & Modern Slavery Principles

BP Labour Rights & Modern Slavery Principles © BP 2019 We are committed to respecting workers’ rights, in line with International Labour Organisation Core Conventions on Rights at Work and expect our contractors, suppliers and joint ventures we participate in to do the same. Our expectation is that workers in our operations, joint ventures and supply chains are not subject to abusive or inhumane practices, such as child labour, forced labour, trafficking, slavery or servitude, discrimination, or harassment. The below principles are intended to assist our businesses as they work to check performance on this expectation, including with our contractors and suppliers. 1. Terms: Workers have clear, written employment terms 8. Working time and rest: Workers are not required to before deployment in a language they understand, and in work unreasonable hours, hours beyond legal limits, or line with terms at point of recruitment, which are without appropriate breaks and defined leave periods. consistently upheld.1 9. Grievance: A grievance process is in place by which 2. Legal status: Workers are legally authorized to work for workers can make complaints, including anonymously, and their employer and possess the necessary visas, work receive appropriate responses and timely updates on the permits, and any similar legal documentary requirements. status of concerns. Concerns may be raised through any process (formal or informal) without fear of retaliation, 3. Protection of Young Persons: Workers below 15 or discrimination or harassment. the legal minimum working age (whichever is higher) are not hired, either directly or indirectly. 10. Working conditions and accommodation: Workers enjoy a safe and hygienic working environment. -

Long-Term Unemployment and the 99Ers

Long-Term Unemployment and the 99ers An Emerging Issues Report from the January 2012 Long-Term Unemployment and the 99ers The Issue Long-term unemployment has been the most stubborn consequence of the Great Recession. In October 2011, more than two years after the Great Recession officially ended, the national unemployment rate stood at 9.0%, with Connecticut’s unemployment rate at 8.7%.1 Americans have been taught to connect the economic condition of the country or their state to the unemployment Millions of Americans— rate, but the national or state unemployment rate does not tell known as 99ers—have the real story. Concealed in those statistics is evidence of a exhausted their UI benefits, substantial and challenging structural change in the labor and their numbers grow market. Nationally, in July 2011, 31.8% of unemployed people every month. had been out of work for at least 52 weeks. In Connecticut, data shows 37% of the unemployed had been jobless for a year or more. By August 2011, the national average length of unemployment was a record 40 weeks.2 Many have been out of work far longer, with serious consequences. Even with federal extensions to Unemployment Insurance (UI), payments are available for a maximum of 99 weeks in some states; other states provide fewer (60-79) weeks. Millions of Americans—known as 99ers— have exhausted their UI benefits, and their numbers grow every month. By October 2011, approximately 2.9 million nationally had done so. Projections show that five million people will be 99ers, exhausting their benefits, by October 2012. -

Overtime and Compensatory Time Updated: June 2021 Federal and State Law

Overtime and Compensatory Time Updated: June 2021 Federal and State Law • Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA): Requires that employees are paid overtime for work in excess of forty (40) hours in a week. • California Labor Code§514: Requires that employees are paid overtime for work in excess of eight (8) hours in a day; while the City and County of San Francisco is not covered by this law because our employees are covered under collective bargaining agreements, we have negotiated that our employees receive this benefit. 2 MOU Overtime – 1x v. 1.5x • One-And-One-Half-Time (1.5x) Overtime (‘OTP’): Earned for hours worked in excess of 8 in a day or 40 hours in a week. • Straight-Time (1x) Overtime (‘OST’): Earned for hours worked outside an employee’s regular work schedule where an employee has not yet worked more than 8 hours in a day or 40 in a week under an MOU based on calculating overtime on hours worked (not hours paid). 3 MOU Overtime – 1x v. 1.5x Example 1: Employee works their regular work schedule from 8:00am to 5:00pm with one hour unpaid lunch and then works four additional hours of overtime. All four hours are earned at the 1.5x overtime rate. Example 2: Same employee takes off two hours of paid sick leave at the beginning of their regular work schedule and then works the remaining six hours of their regular shift. The employee then works four additional hours of overtime of which two are at the 1x rate and two are at the 1.5x overtime rate. -

Unemployment As a Hiring Problem

UNEMPLOYMENT AS A HIRING PROBLEM Robert J. Flanagan CONTENTS Introduction ............................... 124 1 . What is different about the European unemployment experience? . 125 Unemployment flows ........................ 126 II . The failure of supply-side explanations ............... 127 111 . Hiring decisions and unemployment ................. 129 A . Fixed employment costs .................... 129 B. Uncertainty about employee quality .............. 130 C . Uncertainty about future demand ............... 132 D. General implications of the "reluctance to hire" view ..... 133 E . Hiring relationships ...................... 144 Conclusions ............................... 147 Annex: Sources and definitions .................... 151 Bibliography ............................... 152 The author is Professor of Labor Economics. Graduate School of Business. Stanford University. Stanford. California. This paper was prepared as part of a consultancy for the OECD .The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and should not be interpreted to reflect the views of the OECD or its Member Governments. The author is grateful to Janice Callaghan and Rita Varley for research assistance and to David Coe. Franpoise Cor6. David Grubb. John Martin. Franciscus Meyer.zu.Schlochtern. and participants at a seminar held at the OECD for helpful comments and assistance. 123 INTRODUCTION The rise in unemployment in OECD countries during the 1970s and 1980s remains one of the central concerns of economic analysis and policy. Within the general growth of unemployment are several varieties of unemployment experience, however. For example, developments in the 1970s and 1980s reversed one of the previously accepted facts of comparative macroeconomics: average unemployment rates in Europe, which were persistently lower than in the United States before the 1970s, have been persistently higher in the 1980s. Moreover, there is significant variation in the unemployment experience within Europe. -

Memorandum for All State Employees

KANSAS ADJUTANT GENERAL’S DEPARTMENT ________________________________________________________________________ MEMORANDUM FOR ALL STATE EMPLOYEES FROM: TAG-SHRO SUBJECT: Overtime and Other Compensation TAG Policy No. 034-07 EFFECTIVE DATE: March 1, 2017; amended April 1, 2018; amended Sept. 1, 2018 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ POLICY STATEMENT: It is the policy of the Adjutant General’s Department to comply with State and Federal laws and regulations related to overtime compensation and to establish guidelines for the fair and equitable administration of overtime and other forms of compensation while meeting the operational needs of the Department. DEFINITIONS: Additional Regular Pay. Hours paid in excess of 40 hours in a work week at the employee’s regular hourly rate when hours were not actually worked and do not qualify for overtime are Additional Regular Pay. Call-In Call-Back. Calling an employee into work on a regular day off or back to work following a regular scheduled work day is Call-In Call-Back. Compensatory Time. Time off, in lieu of monetary payment, for overtime worked which is computed at the rate of one and a half hours per one hour worked is Compensatory Time. Director. The employee who manages a group of employees who make up an office or department of the Adjutant General’s Department is the Director. Established Core Hours. The Established Core Hours for the Adjutant General’s Department is 6:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. The work schedule for employees must begin and end within the Core Hours unless the work of the position requires shift or other non-standard work schedules.