Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telecommuting Pluses & Pitfalls

Telecommuting Pluses & Pitfalls Brenda B. Thompson Attorney M. LEE SMITH PUBLISHERS LLC Brentwood, Tennessee This special report provides practical information concerning the subject matters covered. It is sold with the understanding that neither the publisher nor the writer is rendering legal advice or other professional service. Some of the information provided in this special report contains a broad overview of federal law. The law changes regularly, and the law may vary from state to state and from one locality to another.You should consult a competent attorney in your state if you are in need of specific legal advice concerning any of the subjects addressed in this special report. © 1996, 1999 M. Lee Smith Publishers LLC 5201 Virginia Way P.O. Box 5094 Brentwood,Tennessee 37024-5094 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Thompson, Brenda B. Telecommuting pluses & pitfalls / Brenda B.Thompson. p. cm. ISBN 0-925773-30-1 (coil binding) 1.Telecommunication — Social aspects — United States. 2.Telecommunication policy — United States. 3. Information technology — Social aspects — United States. I.Title. HE7775.T47 1996 96-21827 658.3'128 — dc20 CIPiw Printed in the United States of America Contents INTRODUCTION ....... 1 1 — THE TELECOMMUTING TREND....... 3 Types of Telecommuting....... 3 The Benefits of Telecommuting....... 4 A Sampling of Current Telecommuting Programs....... 5 To Telecommute or Not to Telecommute....... 7 2 — DECIDING WHO WILL TELECOMMUTE....... 9 Selecting Employees....... 9 Dealing with a Union...... -

Coronavirus-Related Whistleblower Claims: What Employers Need to Know

Coronavirus-Related Whistleblower Claims: What Employers Need to Know May 6, 2020 Presenters Steven J. Pearlman Lloyd B. Chinn Harris M. Mufson Pinchos (Pinny) Goldberg Partner (Chicago) Partner (New York) Partner (New York) Associate (New York) T: +1.312.962.3545 T:+1.212.969.3341 T: +1.212.969.3794 T: +1.212.969.3074 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2 Coronavirus-Related Whistleblower Claims May 6, 2020 COVID-19 Wrongful Death Suit: Evans v. Walmart • First known COVID-19 wrongful death suit - filed in Illinois • Decedent contracted COVID-19 while working at a Walmart store ‒ Another employee who worked at the store died of COVID-19 shortly after the decedent • Complaint alleges: ‒ Walmart failed to implement safety measures recommended by CDC/OSHA ‒ Management did not clean and sterilize the store, provide employees with PPE, or implement social distancing ‒ Walmart did not bar employees with symptoms of COVID-19 ‒ Walmart did not warn employees that other workers had COVID-19 3 Coronavirus-Related Whistleblower Claims May 6, 2020 Whistleblower/Retaliation Claims on the Rise • Reports of employees alleging retaliation for reporting lack of safety measures and personal protective equipment (“PPE”) ‒ Health care workers ‒ Warehouse employees • 1,000+ OSHA complaints regarding lack of COVID-19 protections • OSHA Press Release “reminding employers that it is illegal to retaliate against workers because they report unsafe and unhealthful working conditions during the coronavirus” -

Workplace Conflict and How Businesses Can Harness It to Thrive

JULY 2008 JULY WORKPLACE CONFLICT AND HOW BUSINESSES CAN Maximizing People Performance HARNESS IT TO THRIVE United States Asia Pacific CPP, Inc. CPP Asia Pacific (CPP-AP) 369 Royal Parade Fl 7 Corporate Headquarters P.O. Box 810 1055 Joaquin Rd Fl 2 Parkville, Victoria 3052 Mountain View, CA , 94043 Tel: 650.969.8901 Australia Fax: 650.969.8608 Tel: 61.3.9342.1300 REPORT HUMAN CAPITAL Website: www.cpp.com Email: [email protected] DC Office Beijing 1660 L St NW Suite 601 Tel: 86.10.6463.0800 Washington DC 20036 Email: [email protected] Tel: 202.887.8420 Fax: 202.8878433 Hong Kong Website: www.cpp.com Tel: 852.2817.6807 Email: [email protected] Research Division 4801 Highway 61 Suite 206 India White Bear Lake, MN 55110 Tel: 91.44.4201.9547 Email: [email protected] Customer Service Product orders, inquiries, and support Malaysia Toll free: 800.624.1765 Tel: 65.6333.8481 CPP GLOBAL Tel: 650.969.8901 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Shanghai Professional Services Tel: 86.21.5386.5508 Consulting services and inquiries Email: [email protected] Toll free: 800.624.1765 Tel: 650.969.8901 Singapore Website: www.cpp.com/contactps Tel: 65.6333.8481 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Mexico CPP, Inc Toll free: 800.624.1765 ext 296 Email: [email protected] Maximizing People Performance WORKPLACE CONFLICT AND HOW BUSINESSES CAN HARNESS IT TO THRIVE by Jeff Hayes, CEO, CPP, Inc. FOREWORD OPP® is one of Europe’s leading business psychology firms. -

"Telecommuting Policy"

State of Delaware Department of Human Resources TELECOMMUTING POLICY Policy #: To be announced. Authority: Supersedes: June 22, 2020 and any Agency policy on Effective Date: May 19, 2021 the same or related matter. Application: Executive Branch Agencies Signature: 1. POLICY PURPOSE STATEMENT This policy sets forth the State of Delaware’s (State) policy regarding telecommuting and establishes the requirements for Agencies to designate alternate work locations in order to promote general work efficiencies and to provide continuity of operations in the event employees must use an alternate work location. 2. SCOPE This policy applies to Executive Branch Agency employees. This Statewide Executive Branch policy supersedes any Executive Branch Agency policy, procedure or guideline pertaining or otherwise related to telecommuting. 3. DEFINITIONS AND ACRONYMS • Alternate Work Location - Approved work locations other than employees’ on-site work location where official State business is performed. Such locations may include, but are not limited to, employees’ residence and/or satellite offices. • On-site Work Location - An employer’s primary location where employees are assigned to work. • Reasonable Accommodation - Title I of the ADA provides for reasonable accommodations to qualified employees with disabilities, unless to do so would cause undue hardship. In general, an accommodation is a change in the work environment or in the way things are customarily done that would enable an individual with a disability to enjoy equal employment opportunities. • Telecommuting - A work arrangement in which employees perform essential and non-essential functions of their job at an alternate work location, in accordance with this telecommuting policy and their telecommuting agreement. Telecommuting is also referred to as telework or remote work and has the same meaning in this document. -

Evaluation of the Puget Sound Telecommuting Demonstration

Evaluation of the Puget Sound Telecommuting Demonstration Dee Christensen, Michael Farley, Maureen Quaid and laurel Heifetz Washington State Energy Office Introduction Program Implementation The transportation sector accounts for 28 percent of all Twenty-five organizations and about 250 telecommuters, energy consumption in the United States and is a major their co-workers, and supervisors are involved in the contributor to the nation's air pollution problems (U.S. Demonstration. WSEO conducted an extensive recruitment Department of Energy May 1991. State Energy Data of organizations representing a cross section of the Paget Report). Recent improvements in automotive fuel effi Sound economy. Each organization received assistance in ciency have been overwhelmed by increases in vehicle developing telecommuting policies and procedures, select miles travelled. According to the Federal Highway ing telecommuters, and training their telecommuters and Administration, between 1960 and 1980 traffic volumes their supervisors. almost doubled, while the population grew by 26 percent. Also, traffic congestion is expected to increase by Recruitment 400 percent over the next 20 years on the interstate freeway system and over 200 percent on surface roads. Initial recruitment of potential participating organizations for the Demonstration began with the June 1989 In order to reduce energy consumption and air pollution in "Governor's Conference on Telecommuting: An Alternate the transportation sector, vehicle use and traffic congestion Route To Work.· At the conference, organization repre must be decreased. Transportation demand management sentatives were surveyed to determine their level of (TDM) strategies attempt to accomplish this by promoting interest in pursuing the telecommuting option within their alternatives to single-occupant vehicles such as transit, organization. -

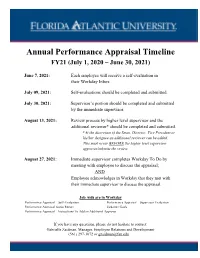

Performance Appraisal Timeline And

Annual Performance Appraisal Timeline FY21 (July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021) June 7, 2021: Each employee will receive a self-evaluation in their Workday Inbox July 09, 2021: Self-evaluations should be completed and submitted. July 30, 2021: Supervisor’s portion should be completed and submitted by the immediate supervisor. August 13, 2021: Review process by higher level supervisor and the additional reviewer* should be completed and submitted. *At the discretion of the Dean, Director, Vice President or his/her designee an additional reviewer can be added. This must occur BEFORE the higher level supervisor approves/submits the review. August 27, 2021: Immediate supervisor completes Workday To Do by meeting with employee to discuss the appraisal; AND Employee acknowledges in Workday that they met with their immediate supervisor to discuss the appraisal. Job Aids are in Workday Performance Appraisal – Self-Evaluation Performance Appraisal – Supervisor Evaluation Performance Appraisal Status Report Updating Goals Performance Appraisal – Instructions To Add an Additional Approver If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact: Gabrielle Zaidman, Manager, Employee Relations and Development (561) 297-3072 or [email protected] Annual Performance Appraisal Process FY21 (July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021) We are excited to kick off the performance appraisal process for all AMP and SP employees, for work completed in FY21 (July 1, 2020 - June 30, 2021). Please note that all work completed after July 1, 2021, should be included in the performance appraisal for next year, FY22. The following are the steps to complete the performance appraisal process. Note that all notifications will appear in your WD Inbox: Each employee will receive a self-evaluation in their WD Inbox on June 7, 2021. -

City Employee Handbook 2020

Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT ................................................................................................................ 7 EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY POLICY ...................................................................................... 8 CODE OF ETHICS / CONFLICTS OF INTEREST ......................................................................................... 9 ROMANTIC AND/OR SEXUAL RELATIONSHIP WITH OTHER EMPLOYEES ............................................ 10 DOING BUSINESS WITH OTHER EMPLOYEES ....................................................................................... 10 OUTSTANDING WARRANT POLICY ...................................................................................................... 10 REPORTING ARRESTS .......................................................................................................................... 11 IMMIGRATION LAW COMPLIANCE ..................................................................................................... 11 JOB DESCRIPTIONS .............................................................................................................................. 12 DISABILITY ACCOMMODATION (ADA REQUESTS) ............................................................................... 16 Definition of reasonable accommodation ...................................................................................... 16 Examples of reasonable accommodation ...................................................................................... -

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery Siobhán McGrath Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science, New School University Economic Development & Global Governance and Independent Study: William Milberg Spring 2005 1. Introduction It is widely accepted that capitalism is characterized by “free” wage labor. But what is “free wage labor”? According to Marx a “free” laborer is “free in the double sense, that as a free man he can dispose of his labour power as his own commodity, and that on the other hand he has no other commodity for sale” – thus obliging the laborer to sell this labor power to an employer, who possesses the means of production. Yet, instances of “unfree labor” – where the worker cannot even “dispose of his labor power as his own commodity1” – abound under capitalism. The question posed by this paper is why. What factors can account for the existence of unfree labor? What role does it play in an economy? Why does it exist in certain forms? In terms of the broadest answers to the question of why unfree labor exists under capitalism, there appear to be various potential hypotheses. ¾ Unfree labor may be theorized as a “pre-capitalist” form of labor that has lingered on, a “vestige” of a formerly dominant mode of production. Similarly, it may be viewed as a “non-capitalist” form of labor that can come into existence under capitalism, but can never become the central form of labor. ¾ An alternate explanation of the relationship between unfree labor and capitalism is that it is part of a process of primary accumulation. -

Evaluation of a Program to Reduce Bullying in an Elementary School Jordan Elizabeth Davis Western Kentucky University, J E [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 8-2011 Evaluation of a Program to Reduce Bullying in an Elementary School Jordan Elizabeth Davis Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the School Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Jordan Elizabeth, "Evaluation of a Program to Reduce Bullying in an Elementary School" (2011). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1079. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVALUATION OF A PROGRAM TO REDUCE BULLYING IN AN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Psychology Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Specialist in Education By Jordan Elizabeth Davis August 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my committee. I appreciate each committee member’s time and hard work on this project. More specifically, Dr. Jones has been very encouraging and flexible. Without her assistance, my thesis project would not have been possible. I would also like to thank my colleague, Kristin Shiflet. She has kept me on track throughout the course of my school psychology internship. She provided motivation and was responsible for implementing materials from the Bully Free Classroom. Kristin also collected the data and coded all information for confidentiality purposes. Her efforts and dedication to this project is much appreciated. -

Managing the Distribution of Employee Workload of the Hospital Staff

IJRDO-Journal of Business Management ISSN: 2455-6661 Managing the Distribution of Employee Workload of the Hospital Staff A. Sravani Associate Professor, Department of Business Management, Sarojini Naidu Vanita Maha Vidyalaya, Exhibition Grounds, Nampally, Hyderabad – 01, Telangana State, India Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Attracting, recruiting, motivating and retaining the workforce is the main course of action for any organisations and also the success of any organization is highly dependent on how they maintain these practices. All this happens when the organisation will be providing fruitful Compensation Packages and the most important is the way the workload is distributed. Distribution of workload cannot be burdened or overburdened to any employee associated with the organisation. More over in today's world the organizations need to be more elastic so that they are set to build up their personnel to be fit for the present competition. Therefore, organizations are required to adopt a strategy to better manage the ‘Workload of the Employees’ to satisfy the both organizational objectives in developing and employee needs of satisfaction. Volume-4 | Issue-1 | January,2018 40 IJRDO-Journal of Business Management ISSN: 2455-6661 In the total Work environment the term ‘employee workload’ refers to the managing of the workload management. Financially assisted programs are another way wherein organisation recognizes their responsibility to enlarge jobs and working conditions, including welfare programs that are admirable for the employees as well as for profitable growth of the organization. Employee workload program elements are such as – Recognition, Goodwill, Allowances, Perks, increments in the salary, Reward systems, a concern for employee job security and Job satisfying, career growth and employee participation in decision making process and so on. -

OSHA WHISTLEBLOWER STAKEHOLDER MEETING October 13, 2020 Minutes

OSHA WHISTLEBLOWER STAKEHOLDER MEETING October 13, 2020 Minutes The OSHA Whistleblower Stakeholder Meeting was called to order by Rob Swick at 1:00 pm ET on Tuesday, October 13, 2020. The meeting was held via teleconference. The following members of the public were present: NAME TITLE & ORGANIZATION Adele Abrams President, Law Office of Adele L. Abrams PC Julie Alexander Director of General Industry, Indiana Department of Labor Jesse Ashley Sr. Manager, EHS, SFC GSC Danielle Avtan Compliance Officer, PCIHIPAA Daniell Barcena N/A Kurt Barry N/A Kimberly Barsa Branch Chief, IRS Office of Chief Counsel Henry Borja Machine Union (IAM) Stores Safety Coordinator, United Airlines Skyler Bouwkamp Supervisor for Whistleblowers/Intake, IOSHA Richard Bozek Director, Environmental and Health & Safety Policy, Edison Electric Institute Michael Brannon Senior Counsel- Health, Safety and Environmental, Quanta Services, Inc. Ariel Braunstein Attorney, Morgan, Lewis & Brockius LLP Deitra Brown Assistant Clinical Director, Texas Children's Hospital Valerie Butera N/A Scott Clausen Associate, Morgan Lewis Kevin Collins Partner, Bracewell LLP Trent Cotney CEO, Cotney Construction Law, LLP Javier Diaz Assistant Attorney General, State of Alaska Department of Law April Dickerson Manager of Quality Assurance & Safety Compliance, RadNet Management, Inc. Jasmin Eapen Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist, MD Anderson Cancer Center Justin Edwards Compliance and Career Development Manager, HVO Karen Engle Whistleblower and CSHO, Indiana Department of Labor Robert -

The Bullying of Teachers Is Slowly Entering the National Spotlight. How Will Your School Respond?

UNDER ATTACK The bullying of teachers is slowly entering the national spotlight. How will your school respond? BY ADRIENNE VAN DER VALK ON NOVEMBER !, "#!$, Teaching Tolerance (TT) posted a blog by an anonymous contributor titled “Teachers Can Be Bullied Too.” The author describes being screamed at by her department head in front of colleagues and kids and having her employment repeatedly threatened. She also tells of the depres- sion and anxiety that plagued her fol- lowing each incident. To be honest, we debated posting it. “Was this really a TT issue?” we asked ourselves. Would our readers care about the misfortune of one teacher? How common was this experience anyway? The answer became apparent the next day when the comments section exploded. A popular TT blog might elicit a dozen or so total comments; readers of this blog left dozens upon dozens of long, personal comments every day—and they contin- ued to do so. “It happened to me,” “It’s !"!TEACHING TOLERANCE ILLUSTRATION BY BYRON EGGENSCHWILER happening to me,” “It’s happening in my for the Prevention of Teacher Abuse repeatedly videotaping the target’s class department. I don’t know how to stop it.” (NAPTA). Based on over a decade of without explanation and suspending the This outpouring was a surprise, but it work supporting bullied teachers, she target for insubordination if she attempts shouldn’t have been. A quick Web search asserts that the motives behind teacher to report the situation. revealed that educators report being abuse fall into two camps. Another strong theme among work- bullied at higher rates than profession- “[Some people] are doing it because place bullying experts is the acute need als in almost any other field.