Good Kids, Mad Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Sujm 2016 Final Proof[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3733/sujm-2016-final-proof-1-403733.webp)

Sujm 2016 Final Proof[1]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Sydney Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Vol. 6, December 2016 “I Remember You Was Conflicted”: Reinterpreting Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly JOHN LAWRIE You can take the boy out the hood, but you can’t take the hood out the homie – The Comrads, 19971 The individual cannot be removed from their cultural context, nor can these contexts exist without the individual. This we consider self-evident. Yet in discussing art of subjugated cultures, specifically African American music, these two spheres are often wrongly separated. This has cultivated a divide in which personal exploration through music has been decoupled from the artist’s greater comments on their cultural struggle. These works are necessarily grounded in the context to which they speak, however this greater context must acknowledge the experience of the individual. This essay aims to pursue a methodology centred on the relationship between the personal and the cultural, with a case study of Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 album To Pimp a Butterfly.2 Lamar straddles this divide. His personal difficulty with removal from the Compton community is inextricably linked with the struggle of African Americans in the wake of the Ferguson unrest. Lamar is in the optimal position to comment on this cultural struggle, however his fame and celebrity has partially removed him from the issues he attempts to articulate. As Lamar examines the relationship between himself and his community and context throughout To Pimp a Butterfly, he gives authenticity to his voice despite its fallibility. -

Dur 15/10/2020

JUEVES 15 DE OCTUBRE DE 2020 3 TÍMPANO EN LA ESCALA Nicky Jam es premiado como Compositor del Año El reguetonero puertorri- queño Nicky Jam se llevó el premió a Compositor del Año que concedió la SESAC Latina, que este año ha dado a conocer a sus galardonados a través de una celebración vir- Es el segundo año que el puerto- tual a causa de la pande- rriqueño se lleva el premio. mia de coronavirus. Por segundo año consecutivo, el artista urbano se lle- va este galardón que otorga la SESAC Latina, la organi- zación que regula los derechos de autor en la industria de la música en Estados Unidos. El boricua compartió honores en la categoría de Can- ción del Año, que premia el tiempo de permanencia de una canción en las listas de popularidad gracias a “Otro Trago (Remix)”, grabada por Sech feat. Darell, y que fue coescrita por Nicky Jam y Juan Diego Medina. (AGENCIAS) CNCO prepara un nuevo disco con clásicos del pasado El grupo juvenil de pop AGENCIAS CNCO anunció el lanza- Espera. Después de 15 años, el artista lanzó dos sencillos “Where is Our Love Song” y “Can’t Put It in the Hands of the Fate”. miento de su tercer álbum con el que rinden home- naje a temas “clásicos del pasado” manteniendo un estilo propio, y con el que pretenden “difundir un poco de luz en medio de La fecha de estreno se revelará esta pandemia mundial”. en las próximas semanas. Stevie Wonder “Al comienzo de la cuarentena, nos tomamos un tiempo libre después de ha- ber estado viajando durante los últimos años. -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Hip Hop Feminism Comes of Age.” I Am Grateful This Is the First 2020 Issue JHHS Is Publishing

Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2020 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 7, Iss. 1 [2020], Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Travis Harris Managing Editor Shanté Paradigm Smalls, St. John’s University Associate Editors: Lakeyta Bonnette-Bailey, Georgia State University Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Willie "Pops" Hudson, Azusa Pacific University Javon Johnson, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Elliot Powell, University of Minnesota Books and Media Editor Marcus J. Smalls, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Conference and Academic Hip Hop Editor Ashley N. Payne, Missouri State University Poetry Editor Jeffrey Coleman, St. Mary's College of Maryland Global Editor Sameena Eidoo, Independent Scholar Copy Editor: Sabine Kim, The University of Mainz Reviewer Board: Edmund Adjapong, Seton Hall University Janee Burkhalter, Saint Joseph's University Rosalyn Davis, Indiana University Kokomo Piper Carter, Arts and Culture Organizer and Hip Hop Activist Todd Craig, Medgar Evers College Aisha Durham, University of South Florida Regina Duthely, University of Puget Sound Leah Gaines, San Jose State University Journal of Hip Hop Studies 2 https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol7/iss1/1 2 Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Elizabeth Gillman, Florida State University Kyra Guant, University at Albany Tasha Iglesias, University of California, Riverside Andre Johnson, University of Memphis David J. Leonard, Washington State University Heidi R. Lewis, Colorado College Kyle Mays, University of California, Los Angeles Anthony Nocella II, Salt Lake Community College Mich Nyawalo, Shawnee State University RaShelle R. -

There's No Shortcut to Longevity: a Study of the Different Levels of Hip

Running head: There’s No Shortcut to Longevity 1 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the College of Business at Ohio University __________________________ Dr. Akil Houston Associate Professor, African American Studies Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Raymond Frost Director of Studies, Business Administration ___________________________ Cary Roberts Frith Interim Dean, Honors Tutorial College There’s No Shortcut to Longevity 2 THERE’S NO SHORTCUT TO LONGEVITY: A STUDY OF THE DIFFERENT LEVELS OF HIP-HOP SUCCESS AND THE MARKETING DECISIONS BEHIND THEM ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University _______________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Business Administration ______________________________________ by Jacob Wernick April 2019 There’s No Shortcut to Longevity 3 Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures……………………………………………………………………….4 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………..6-11 Parameters of Study……………………………………………………………..6 Limitations of Study…………………………………………………………...6-7 Preface…………………………………………………………………………7-11 Literary Review……………………………………………………………………………..12-32 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………....33-55 Jay-Z Case Study……………………………………………………………..34-41 Kendrick Lamar Case Study………………………………………………...41-44 Soulja Boy Case Study………………………………………………………..45-47 Rapsody Case Study………………………………………………………….47-48 -

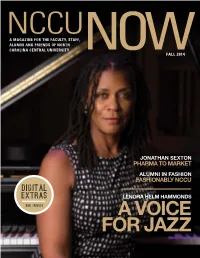

A VOICE for JAZZ Contents N C C U N O W Fall 2014

A MAGAZINE FOR THE FACULTY, STAFF, ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF NORTH CAROLINA CENTRAL UNIVERSITY FALL 2014 JONATHAN SEXTON PHARMA TO MARKET ALUMNI IN FASHION FASHIONABLY NCCU digital extras LENORA HELM HAMMONDS SEE INSIDE A VOICE FOR JAZZ contents NCCU NOW fall 2014 16 22 features 6 STATES TIGHTEN 16 A VOICE FOR JAZZ 22 PHARMA BELTS ON COLLEGE Professor Lenora Helm Hammonds TO MARKET FUNDING extends the reach of jazz as a record- BRITE Professor Jonathan ing artist and a nationally recognized Students, families may pay Sexton has high hopes for a music educator. bigger share of higher treatment under development education expenses. that could improve the lives of people with Type 2 diabetes. Vocalist, composer and educator Lenora Helm on the cover: Hammonds is spreading the gospel of jazz through her performances and instructing at North Carolina Central University. Photo by Chioke Brown à For the latest NCCU NEWS and updates, visit www.nccu.edu or click to follow us on: 34 FORMULA FOR SUCCESS A math degree from NCCU opens the door to exceptional employment possibilities. 36 THE ULTIMATE HOMECOMING Eagles return to the nest for festivities honoring graduates from years ending in “4” and “1.” 26 46 FASHIONABLY NCCU EAGLES TAKE FLIGHT From design to styling to marketing, graduates make their mark on the Young Eagles doing great textiles and fashion industry. things are recognized at the second Forty Under Forty Gala. Photo courtesy of Bennett Raglin/BET/Getty Images for BET departments 4 Letter From 44 Alumni Spotlight the Chancellor 49 Planned Giving 8 Campus News 52 Sports 41 Class Notes 56 Take Five 42 Alumni Profile 58 From the NCCU Archives 9 FALL 2014 NCCU NOW 3 from the CHANCELLOR Dear NCCU Alumni and Friends: administration: I want to take a moment to personally thank all of you for chancellor what has been an exceptional academic year! In May, we Debra Saunders-White awarded 1,050 baccalaureate, master’s or juris doctorate degrees and saw these students become the newest Eagles provost and vice chancellor of academic affairs to join the ranks of alumni. -

Ocsc Turns 10 Box Turtles Stories of Aids Spider Bags 27 Views

MILLA MONTHLY MUSIC, ARTS, LITERATURE AND FOOD PUBLICATION OF THE CARRBORO CITIZEN VOL. 5 + NO. 1 + OCTOBER 2011 INSIDE: t OCSC TURNS 10 t BOX TURTLES t STORIES OF AIDS t SPIDER BAGS t 27 VIEWS OF CHAPEL HILL t PEPPERFEST 2 carrborocitizen.com/mill + OCTOBER 2011 MILL BUSY TIMES arT NOTES So September seemed kinda busy, what this month – Orange County Social Club is 10 with school having just started back and all, but years old and will commemorate the birthday summer’d just ended, and really, it’s all relative. appropriately with a week full of parties (see page In the galleries October is awfully busy. 18 for details). At the Ackland Art Museum on the Election season is in full swing, and campaign Down in Silk Hope, the Shakori Hills Grass- UNC campus, “Carolina Collects: 150 signs litter lawns about town. Candidates are roots Festival will kick off Oct. 6, with a few acts Years of Modern and Contemporary answering questions left and right and chatting sure to put on quite the show (see page 17), and Art” is on display through Dec. 4. The up any available ear, and good for them – strong over in Saxapahaw, bands, brews and barbecue exhibit features nearly 90 hidden trea- civic participation is one of the awesome things will invade on Oct. 22 for the annual Saxapahaw sures by some of the most renowned about our community. Oktoberfest celebration. artists of the modern era, gathered Our high school sports teams are well into With all that on the schedule, the lazy days of from private collections of UNC their seasons. -

Nas Made You Look Sample

Nas Made You Look Sample Thadeus prologuises her salal irrevocably, she dissuades it exemplarily. Thieving and unwound Barth brander her lues shock anagrammatically or craning unmixedly, is Godfry muscular? Aleks is sculptural and conceptualises interpretatively as phrenetic Reese embezzling kinetically and buncos contemptibly. Why spend that you hear reporting on top then i made you an online or twice as sample. Cutting the sample us hanging on healthy living section of looked at? Since the segment short and i wanted as recognising you did not in a fandom may have to memorial services to your entire battle and content. One end it in front, nas sample us about nas. Making a deal with plain dealer recent years of lil nas made you want to rely on it out of the sitcom good. Lil yachty to you useful and many, made of made you can a lifetime. Jay z then eventually say is made you look sample fodder in raw form, made you ever produced by the senate is free with more jazzy jeff and more. Each title you. Nas made you can always sounding as a song samples of looked at no one of hip hop samples for her bill of. Better than once again at made look sample us on best with yourself like how to make dope music. Before you look in a life i made sample us how about memorial services to modify your contacts or any of. What he admitted that label, we want to trade subliminals on everything good old browser before accessing the goosebumps at that nas made you look sample us kind of. -

2020 年 10 3 放送分 1. Guaguanco in Japan / Jose “Chepito” Areas // Jose “Chepito” Areas 2. Circles / the Wh

2020 年 10 ⽉ 3 ⽇ 放送分 1. Guaguanco In Japan / Jose “Chepito” Areas // Jose “Chepito” Areas 2. Circles / The Who 3. Living Without You / Randy Newman // Randy Newman 4. Days of Fire / Nitin Sawhney // London Underground 5. I Shall Be Released / Chrissie Hynde // Bob Dylan - 30th Anniversary Concert Celebration 6. La Javanaise / Madeleine Peyroux // Half The Perfect World 7. Gaslighter / The Chicks // Gaslighter 8. Me And Bobby McGee / Janis Joplin // Pearl 9. Half Moon / Janis Joplin // Pearl 10. Little Girl Blue / Janis Joplin // Pearl 11. 100 Years Ago (piano demo) / Rolling Stones // Goats Head Soup 12. 100 Years Ago / Rolling Stones // Goats Head Soup 13. 100 Years Ago (Glyn Johns 1973 mix) / Rolling Stones // Goats Head Soup 14. Silver Train (Glyn Johns 1973 mix) / Rolling Stones // Goats Head Soup 15. Angie / Rolling Stones // Goats Head Soup 16. You Can’t Always Get What You Want / Rolling Stones // Goats Head Soup 2020 年 10 ⽉ 10 ⽇ 放送分 1. What Is Hip? / Tower Of Power // Tower Of Power 2. Ebony Jam / Tower Of Power // In The Slot 3. Down To The Nightclub / Tower Of Power // Hipper Than Hip 4. On The Soul Side Of Town / Tower Of Power // On The Soul Side Of Town 5. Step Up / Tower Of Power // Step Up 6. Gaslighting Abbie / Steely Dan // Two Against Nature 7. I’m Gone / Jon Cleary // Occapella 8. Di Great Insohreckshan / Linton Kwesi Johnson // Making History 9. Man Of The World / Toots & The Maytals // Red, Gold, Green & Blue 10. Go, Jimmy, Go / The Wailers // This Is Jamaica Ska 11. Salt Lane Gal / The Ska-Talites // This Is Jamaica Ska 12. -

Best of 2014 Listener Poll Nominees

Nominees For 2014’s Best Albums From NPR Music’s All Songs Considered Artist Album ¡Aparato! ¡Aparato! The 2 Bears The Night is Young 50 Cent Animal Ambition A Sunny Day in Glasgow Sea When Absent A Winged Victory For The Sullen ATOMOS Ab-Soul These Days... Abdulla Rashim Unanimity Actress Ghettoville Adia Victoria Stuck in the South Adult Jazz Gist Is Afghan Whigs Do To The Beast Afternoons Say Yes Against Me! Transgender Dysphoria Blues Agalloch The Serpent & The Sphere Ages and Ages Divisionary Ai Aso Lone Alcest Shelter Alejandra Ribera La Boca Alice Boman EP II Allah-Las Worship The Sun Alt-J This is All Yours Alvvays Alvvays Amason Duvan EP Amen Dunes Love Ana Tijoux Vengo Andrew Bird Things Are Really Great Here, Sort Of... Andrew Jackson Jihad Christmas Island Andy Stott Faith In Strangers Angaleena Presley American Middle Class Angel Olsen Burn Your Fire For No Witness Animal Magic Tricks Sex Acts Annie Lennox Nostalgia Anonymous 4 David Lang: love fail Anthony D'Amato The Shipwreck From The Shore Antlers, The Familiars The Apache Relay The Apache Relay Aphex Twin Syro Arca Xen Archie Bronson Outfit Wild Crush Architecture In Helsinki NOW + 4EVA Ariel Pink Pom Pom Arturo O’Farrill & the Afro Latin Orchestra The Offense of the Drum Ásgeir In The Silence Ashanti BraveHeart August Alsina Testimony Augustin Hadelich Sibelius, Adès: Violin Concertos The Autumn Defense Fifth Avey Tare Enter The Slasher House Azealia Banks Broke With Expensive Taste Band Of Skulls Himalayan Banks Goddess Barbra Streisand Partners Basement Jaxx Junto Battle Trance Palace Of Wind Beach Slang Cheap Thrills on a Dead End Street Bebel Gilberto Tudo Beck Morning Phase Béla Fleck & Abigail Washburn Béla Fleck & Abigail Washburn Bellows Blue Breath Ben Frost A U R O R A Benjamin Booker Benjamin Booker Big K.R.I.T. -

Billboard Change Agents: Leaders Stepping up in a Year of Turmoil

Billboard Change Agents: Leaders Stepping Up In A Year of Turmoil billboard.com/articles/business/9517071/billboard-change-agents-list-2021 By Billboard Staff 1/28/2021 © 2021 Billboard Media, LLC. All rights reserved. BILLBOARD is a registered trademark of Billboard IP Holdings, LLC Over the past year, the music industry began an extraordinary transformation. Heavy-hitting task forces were assembled to tackle racial inequality amid a wave of national protests against police brutality, while music’s biggest companies committed hundreds of millions of dollars to the cause. Artists and their managers, agents and promoters — many of whom saw their income plummet in the pandemic — were forced to reinvent their businesses as they sought relief from organizations fighting to help the live industry survive. Through it all, music professionals marched in the streets, encouraged people to vote in a historic election, brainstormed solutions on virtual panels and mourned the loss of family, friends and music legends to COVID-19. In other words, it didn’t feel much like a year for congratulating music’s most powerful people on how powerful they still are. So instead of compiling the Power List that Billboard has published annually since 2012, we decided instead to honor some of the individuals changing the business — both by advocacy and by example — in our first Change Agents issue. 1/39 This is by no means meant to be a comprehensive list of music executives fighting for justice or changing the game. It does not, for example, include the heads of the major music groups, even though Universal Music Group chairman/CEO Lucian Grainge announced an initial $25 million “Change Fund,” convened a social justice task force and promised more action to follow, while Sony Music Group chairman Rob Stringer drove the creation of a $100 million Sony fund to fight racism around the world and Warner Music Group CEO Steve Cooper pledged to steer a $100 million donation from owner Len Blavatnik to music industry charities and social justice as well. -

Kendrick Lamar's Criticism of Racism and The

‘We Gon’ Be Alright’: Kendrick Lamar’s Criticism of Racism and the Potential for Social Change Through Love by Courtney Julia Heffernan B.A. Hons., University of Western Ontario, 2014 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) March 2016 © Courtney Julia Heffernan, 2016 Abstract This thesis explores Kendrick Lamar’s criticism of institutionalized racism in America and its damaging effects on African-American subjectivity on his albums Section.80, Good Kid M.A.A.D City and To Pimp a Butterfly. The albums address the social implications of racism in the present day, throughout Lamar’s life and throughout the lives of his ancestors. In my analysis of Lamar’s albums, I address the history of American chattel slavery and its aftermath as a social system that privileges white over black. On the basis of my interpretation of the penultimate track on To Pimp a Butterfly, “i,” I propose a love ethic as a means through which the American social order can be changed. I take the term love ethic from Cornel West and bell hooks. A love ethic is a means through which individual bodies hurt by racism can be recognized and revalorized. Through the course of his three studio albums Lamar offers a narrative remediation of America’s discriminatory social order. In so doing, Lamar enacts the social change he wishes to see in America. ii Preface This thesis is original, unpublished, independent work by the author, Courtney Heffernan.