Sujm 2016 Final Proof[1]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

Dur 15/10/2020

JUEVES 15 DE OCTUBRE DE 2020 3 TÍMPANO EN LA ESCALA Nicky Jam es premiado como Compositor del Año El reguetonero puertorri- queño Nicky Jam se llevó el premió a Compositor del Año que concedió la SESAC Latina, que este año ha dado a conocer a sus galardonados a través de una celebración vir- Es el segundo año que el puerto- tual a causa de la pande- rriqueño se lleva el premio. mia de coronavirus. Por segundo año consecutivo, el artista urbano se lle- va este galardón que otorga la SESAC Latina, la organi- zación que regula los derechos de autor en la industria de la música en Estados Unidos. El boricua compartió honores en la categoría de Can- ción del Año, que premia el tiempo de permanencia de una canción en las listas de popularidad gracias a “Otro Trago (Remix)”, grabada por Sech feat. Darell, y que fue coescrita por Nicky Jam y Juan Diego Medina. (AGENCIAS) CNCO prepara un nuevo disco con clásicos del pasado El grupo juvenil de pop AGENCIAS CNCO anunció el lanza- Espera. Después de 15 años, el artista lanzó dos sencillos “Where is Our Love Song” y “Can’t Put It in the Hands of the Fate”. miento de su tercer álbum con el que rinden home- naje a temas “clásicos del pasado” manteniendo un estilo propio, y con el que pretenden “difundir un poco de luz en medio de La fecha de estreno se revelará esta pandemia mundial”. en las próximas semanas. Stevie Wonder “Al comienzo de la cuarentena, nos tomamos un tiempo libre después de ha- ber estado viajando durante los últimos años. -

Bradley Syllabus for South

Special Topics in African American Literature: OutKast and the Rise of the Hip Hop South Regina N. Bradley, Ph.D. Course Description In 1995, Atlanta, GA, duo OutKast attended the Source Hip Hop Awards, where they won the award for best new duo. Mostly attended by bicoastal rappers and hip hop enthusiasts, OutKast was booed off the stage. OutKast member Andre Benjamin, clearly frustrated, emphatically declared what is now known as the rallying cry for young black southerners: “the South got something to say.” For this course, we will use OutKast’s body of work as a case study questioning how we recognize race and identity in the American South after the civil rights movement. Using a variety of post–civil rights era texts including film, fiction, criticism, and music, students will interrogate OutKast’s music as the foundation of what the instructor theorizes as “the hip hop South,” the southern black social-cultural landscape in place over the last twenty-five years. Course Objectives 1. To develop and utilize a multidisciplinary critical framework to successfully engage with conversations revolving around contemporary identity politics and (southern) popular culture 2. To challenge students to engage with unfamiliar texts, cultural expressions, and language in order to learn how to be socially and culturally sensitive and aware of modes of expression outside of their own experiences. 3. To develop research and writing skills to create and/or improve one’s scholarly voice and others via the following assignments: • Critical listening journal • Nerdy hip hop review **Explicit Content Statement** (courtesy: Dr. Treva B. Lindsey) Over the course of the semester students will be introduced to texts that may be explicit in nature (i.e., cursing, sexual content). -

Confessions of a Black Female Rapper: an Autoethnographic Study on Navigating Selfhood and the Music Industry

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University African-American Studies Theses Department of African-American Studies 5-8-2020 Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry Chinwe Salisa Maponya-Cook Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses Recommended Citation Maponya-Cook, Chinwe Salisa, "Confessions Of A Black Female Rapper: An Autoethnographic Study On Navigating Selfhood And The Music Industry." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2020. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/aas_theses/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of African-American Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in African-American Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF A BLACK FEMALE RAPPER: AN AUTOETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY ON NAVIGATING SELFHOOD AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by CHINWE MAPONYA-COOK Under the DireCtion of Jonathan Gayles, PhD ABSTRACT The following research explores the ways in whiCh a BlaCk female rapper navigates her selfhood and traditional expeCtations of the musiC industry. By examining four overarching themes in the literature review - Hip-Hop, raCe, gender and agency - the author used observations of prominent BlaCk female rappers spanning over five deCades, as well as personal experiences, to detail an autoethnographiC aCCount of self-development alongside pursuing a musiC career. MethodologiCally, the author wrote journal entries to detail her experiences, as well as wrote and performed an aCCompanying original mixtape entitled The Thesis (available on all streaming platforms), as a creative addition to the research. -

Hip Hop Feminism Comes of Age.” I Am Grateful This Is the First 2020 Issue JHHS Is Publishing

Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2020 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 7, Iss. 1 [2020], Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Travis Harris Managing Editor Shanté Paradigm Smalls, St. John’s University Associate Editors: Lakeyta Bonnette-Bailey, Georgia State University Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Willie "Pops" Hudson, Azusa Pacific University Javon Johnson, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Elliot Powell, University of Minnesota Books and Media Editor Marcus J. Smalls, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Conference and Academic Hip Hop Editor Ashley N. Payne, Missouri State University Poetry Editor Jeffrey Coleman, St. Mary's College of Maryland Global Editor Sameena Eidoo, Independent Scholar Copy Editor: Sabine Kim, The University of Mainz Reviewer Board: Edmund Adjapong, Seton Hall University Janee Burkhalter, Saint Joseph's University Rosalyn Davis, Indiana University Kokomo Piper Carter, Arts and Culture Organizer and Hip Hop Activist Todd Craig, Medgar Evers College Aisha Durham, University of South Florida Regina Duthely, University of Puget Sound Leah Gaines, San Jose State University Journal of Hip Hop Studies 2 https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol7/iss1/1 2 Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Elizabeth Gillman, Florida State University Kyra Guant, University at Albany Tasha Iglesias, University of California, Riverside Andre Johnson, University of Memphis David J. Leonard, Washington State University Heidi R. Lewis, Colorado College Kyle Mays, University of California, Los Angeles Anthony Nocella II, Salt Lake Community College Mich Nyawalo, Shawnee State University RaShelle R. -

The Legacy of Jazz Poetry in Contemporary Rap: Langston Hughes, Gil Scott-Heron, and Kendrick Lamar

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Undergraduate Honors Theses 2020-07-31 The Legacy of Jazz Poetry in Contemporary Rap: Langston Hughes, Gil Scott-Heron, and Kendrick Lamar Madison Brasher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Brasher, Madison, "The Legacy of Jazz Poetry in Contemporary Rap: Langston Hughes, Gil Scott-Heron, and Kendrick Lamar" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 149. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht/149 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Honors Thesis THE LEGACY OF JAZZ POETRY IN CONTEMPORARY RAP: LANGSTON HUGHES, GIL SCOTT-HERON, AND KENDRICK LAMAR by Madison Hailes Brasher Submitted to Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of graduation requirements for University Honors English Department Brigham Young University August 2020 Advisor: Greg Clark Honors Coordinator: John Talbot ii ABSTRACT THE LEGACY OF JAZZ POETRY IN CONTEMPORARY RAP: LANGSTON HUGHES, GIL SCOTT-HERON, AND KENDRICK LAMAR Madison Brasher English Department Bachelor of Arts Langston Hughes wrote in “Jazz as Communication that: “Jazz is a great big sea. It washes up all kinds of fish and shells and spume and waves with a steady old beat, or off-beat.” In this paper I assert that the rap music of Kendrick Lamar contains the steady off-beat of jazz and carries out the rhetorical legacy of Hughes’ jazz poetry. By marking the key elements of jazz poetry and tracing their presence in rap music, I will show how these elements create a powerful aesthetic experience for audiences that primes them for the rhetorical messages of the artist. -

The Recording Academy®

® The Recording Academy 3030 Olympic Blvd. • Santa Monica, CA 90404 www.grammy.com JAY Z LEADS NOMINATIONS WITH NINE; KENDRICK LAMAR, MACKLEMORE & RYAN LEWIS, JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE, AND PHARRELL WILLIAMS EACH EARN SEVEN; DRAKE AND BOB LUDWIG EACH GARNER FIVE SARA BAREILLES, DAFT PUNK, KENDRICK LAMAR, MACKLEMORE & RYAN LEWIS, AND TAYLOR SWIFT VIE FOR ALBUM OF THE YEAR AT THE 56TH ANNUAL GRAMMY AWARDS® JAN. 26, 2014, LIVE ON CBS LOS ANGELES (Dec. 06, 2013) — Nominations for the 56th Annual GRAMMY Awards® were announced tonight by The Recording Academy® and reflected one of the most diverse years with the Album Of The Year category alone representing the rap, pop, country and dance/electronica genres, as determined by the voting members of The Academy. Once again, nominations in select categories for the annual GRAMMY Awards were announced on primetime television as part of "The GRAMMY® Nominations Concert Live!! — Countdown To Music's Biggest Night®," a one-hour CBS entertainment special broadcast live from Nokia Theatre L.A. LIVE. The 56th Annual GRAMMY Awards will be held on "GRAMMY Sunday," Jan. 26, 2014, at STAPLES Center in Los Angeles and once again will be broadcast live in high-definition TV and 5.1 surround sound on CBS from 8 – 11:30 p.m. (ET/PT). For updates and breaking news, please visit The Recording Academy's social networks on Twitter and Facebook. For a complete nominations list, please visit www.grammy.com. Jay Z tops the nominations with nine; Kendrick Lamar, Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, Justin Timberlake, and Pharrell Williams each garner seven nods; Drake and mastering engineer Bob Ludwig are up for five awards. -

There's No Shortcut to Longevity: a Study of the Different Levels of Hip

Running head: There’s No Shortcut to Longevity 1 This thesis has been approved by The Honors Tutorial College and the College of Business at Ohio University __________________________ Dr. Akil Houston Associate Professor, African American Studies Thesis Adviser ___________________________ Dr. Raymond Frost Director of Studies, Business Administration ___________________________ Cary Roberts Frith Interim Dean, Honors Tutorial College There’s No Shortcut to Longevity 2 THERE’S NO SHORTCUT TO LONGEVITY: A STUDY OF THE DIFFERENT LEVELS OF HIP-HOP SUCCESS AND THE MARKETING DECISIONS BEHIND THEM ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Honors Tutorial College Ohio University _______________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Honors Tutorial College with the degree of Bachelor of Business Administration ______________________________________ by Jacob Wernick April 2019 There’s No Shortcut to Longevity 3 Table of Contents List of Tables and Figures……………………………………………………………………….4 Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………..6-11 Parameters of Study……………………………………………………………..6 Limitations of Study…………………………………………………………...6-7 Preface…………………………………………………………………………7-11 Literary Review……………………………………………………………………………..12-32 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………....33-55 Jay-Z Case Study……………………………………………………………..34-41 Kendrick Lamar Case Study………………………………………………...41-44 Soulja Boy Case Study………………………………………………………..45-47 Rapsody Case Study………………………………………………………….47-48 -

Generative Elements in Kendrick Lamar's to Pimp a Bu Erfly

This Flow Ain’t Free: Generative Elements in Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Buerfly John J. Maessich NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hp://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.19.25.1/mto.19.25.1.maessich.php KEYWORDS: Hop hop, hip-hop, flow, Kendrick Lamar, popular music, semiotics, cultural studies ABSTRACT: This article presents analyses of three songs from To Pimp a Buerfly with respect to the relationship between Lamar’s flow and the instrumental track in each song. A spectrum of flow is proposed, which consists of flow that is at one extreme derivative (metrically and hypermetrically aligned with the instrumental track) and at the other generative (flow and instrumental track are discontinuous). This framework is then considered with respect to normative stylistic considerations and used as a means of interpretation in tandem with the lyrics. Received DATE Volume 25, Number 1, April 2019 Copyright © 2019 Society for Music Theory [1] In his article “On the Metrical Techniques of Flow in Rap Music,” Kyle Adams defined flow in rap music as “all of the rhythmical and articulative features of a rapper’s delivery of the lyrics” (Adams 2009, [6]). He outlines how delivery can affect the expressive quality of the song, discussing a variety of rhythmic techniques that include the placement of accented syllables in relation to the beat, as well as the variance of note length and subdivisions of the beat. He summarizes the defining characteristics of flow into two main categories: metrical techniques and articulative techniques. -

Graduates Prepare to Walk the Stage See Page 4 2 the Gazette | May 7, 2015 Voices

the Gazette VOL. 77, NO. 12 STUDENT VOICE OF LANGSTON UNIVERSITY THURSDAY, MAY 7, 2015 Graduates prepare to walk the stage See Page 4 2 The Gazette | May 7, 2015 Voices The Gazette is produced What is beauty? within the Department of Communication at Langston University. It serves as a teaching tool Professor says it's 'in the eye of the beholder' and public relations vehicle. The newspaper is As a junior at Langston ciety today, ranging from solo album “The Miseduca- published bimonthly and University, I enrolled in the the color of our skin to our tion of Lauryn Hill” in order is dispersed across campus Black Authors in American physical weight to our own to acquire the self-love and every other Thursday, Literature course, in which value system. self-worth she lacks and to except during we read several different Pecola represents a butter- overcome the existential examinations, holidays and texts. fly pimped by the system— angst from which she is suf- extended school breaks. One particular text that a system that oppresses fering. had an impact on me was minorities of all kinds and Society dictates what Toni Morrison’s debut novel constantly tells us all that beauty is and is not. But Adviser/Manager “The Bluest Eye,” published we are not beautiful if we do beauty is a subjective ex- Nicole Turner in 1970. not have blonde hair or blue perience—that is, a mental I enjoyed reading this nov- eyes or even a skinny phy- phenomenon that differs Editor el because it explores themes Wright sique. -

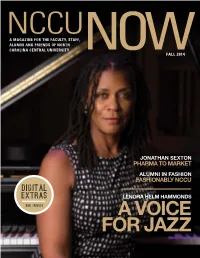

A VOICE for JAZZ Contents N C C U N O W Fall 2014

A MAGAZINE FOR THE FACULTY, STAFF, ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF NORTH CAROLINA CENTRAL UNIVERSITY FALL 2014 JONATHAN SEXTON PHARMA TO MARKET ALUMNI IN FASHION FASHIONABLY NCCU digital extras LENORA HELM HAMMONDS SEE INSIDE A VOICE FOR JAZZ contents NCCU NOW fall 2014 16 22 features 6 STATES TIGHTEN 16 A VOICE FOR JAZZ 22 PHARMA BELTS ON COLLEGE Professor Lenora Helm Hammonds TO MARKET FUNDING extends the reach of jazz as a record- BRITE Professor Jonathan ing artist and a nationally recognized Students, families may pay Sexton has high hopes for a music educator. bigger share of higher treatment under development education expenses. that could improve the lives of people with Type 2 diabetes. Vocalist, composer and educator Lenora Helm on the cover: Hammonds is spreading the gospel of jazz through her performances and instructing at North Carolina Central University. Photo by Chioke Brown à For the latest NCCU NEWS and updates, visit www.nccu.edu or click to follow us on: 34 FORMULA FOR SUCCESS A math degree from NCCU opens the door to exceptional employment possibilities. 36 THE ULTIMATE HOMECOMING Eagles return to the nest for festivities honoring graduates from years ending in “4” and “1.” 26 46 FASHIONABLY NCCU EAGLES TAKE FLIGHT From design to styling to marketing, graduates make their mark on the Young Eagles doing great textiles and fashion industry. things are recognized at the second Forty Under Forty Gala. Photo courtesy of Bennett Raglin/BET/Getty Images for BET departments 4 Letter From 44 Alumni Spotlight the Chancellor 49 Planned Giving 8 Campus News 52 Sports 41 Class Notes 56 Take Five 42 Alumni Profile 58 From the NCCU Archives 9 FALL 2014 NCCU NOW 3 from the CHANCELLOR Dear NCCU Alumni and Friends: administration: I want to take a moment to personally thank all of you for chancellor what has been an exceptional academic year! In May, we Debra Saunders-White awarded 1,050 baccalaureate, master’s or juris doctorate degrees and saw these students become the newest Eagles provost and vice chancellor of academic affairs to join the ranks of alumni.