Vvc-2019.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

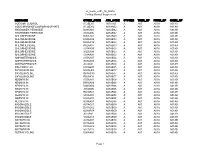

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Cr

Drug Name Plate Number Well Location % Inhibition, Screen Axitinib 1 1 20 Gefitinib (ZD1839) 1 2 70 Sorafenib Tosylate 1 3 21 Crizotinib (PF-02341066) 1 4 55 Docetaxel 1 5 98 Anastrozole 1 6 25 Cladribine 1 7 23 Methotrexate 1 8 -187 Letrozole 1 9 65 Entecavir Hydrate 1 10 48 Roxadustat (FG-4592) 1 11 19 Imatinib Mesylate (STI571) 1 12 0 Sunitinib Malate 1 13 34 Vismodegib (GDC-0449) 1 14 64 Paclitaxel 1 15 89 Aprepitant 1 16 94 Decitabine 1 17 -79 Bendamustine HCl 1 18 19 Temozolomide 1 19 -111 Nepafenac 1 20 24 Nintedanib (BIBF 1120) 1 21 -43 Lapatinib (GW-572016) Ditosylate 1 22 88 Temsirolimus (CCI-779, NSC 683864) 1 23 96 Belinostat (PXD101) 1 24 46 Capecitabine 1 25 19 Bicalutamide 1 26 83 Dutasteride 1 27 68 Epirubicin HCl 1 28 -59 Tamoxifen 1 29 30 Rufinamide 1 30 96 Afatinib (BIBW2992) 1 31 -54 Lenalidomide (CC-5013) 1 32 19 Vorinostat (SAHA, MK0683) 1 33 38 Rucaparib (AG-014699,PF-01367338) phosphate1 34 14 Lenvatinib (E7080) 1 35 80 Fulvestrant 1 36 76 Melatonin 1 37 15 Etoposide 1 38 -69 Vincristine sulfate 1 39 61 Posaconazole 1 40 97 Bortezomib (PS-341) 1 41 71 Panobinostat (LBH589) 1 42 41 Entinostat (MS-275) 1 43 26 Cabozantinib (XL184, BMS-907351) 1 44 79 Valproic acid sodium salt (Sodium valproate) 1 45 7 Raltitrexed 1 46 39 Bisoprolol fumarate 1 47 -23 Raloxifene HCl 1 48 97 Agomelatine 1 49 35 Prasugrel 1 50 -24 Bosutinib (SKI-606) 1 51 85 Nilotinib (AMN-107) 1 52 99 Enzastaurin (LY317615) 1 53 -12 Everolimus (RAD001) 1 54 94 Regorafenib (BAY 73-4506) 1 55 24 Thalidomide 1 56 40 Tivozanib (AV-951) 1 57 86 Fludarabine -

Use of Nifuratel to Treat Infections Caused by Atopobium Species

(19) & (11) EP 2 243 482 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 27.10.2010 Bulletin 2010/43 A61K 31/422 (2006.01) A61P 15/02 (2006.01) A61P 31/04 (2006.01) A61P 13/02 (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 09158221.3 A61P 15/00 (22) Date of filing: 20.04.2009 (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventor: Mailland, Federico AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR CH-6900 Lugano (CH) HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO PL PT RO SE SI SK TR (74) Representative: Pistolesi, Roberto et al Designated Extension States: Dragotti & Associati Srl AL BA RS Via Marina 6 20121 Milano (IT) (71) Applicant: Polichem SA 1526 Luxembourg (LU) (54) Use of nifuratel to treat infections caused by atopobium species (57) The present invention is directed to the use of genitalia in both sexes, as well as bacterial vaginosis, or nifuratel, or a physiologically acceptable salt thereof, to mixed vaginal infections in women, when one or more treat infections caused by Atopobium species. The in- species of the genus Atopobium are among the causative vention is further directed to the use of nifuratel to treat pathogens of those infections. bacteriuria, urinary tract infections, infections of external EP 2 243 482 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 2 243 482 A1 Description [0001] The present invention relates to the use of nifuratel, or a physiologically acceptable salt thereof, to treat infections caused by Atopobium species. -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8870/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-2-or-ehealth-dsi-master-value-set-1028870.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.2-OR] Ehealth DSI – Master Value Set

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.2-OR] eHealth DSI – Master Value Set Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.2-OR Wed Nov 08 16:16:10 CET 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 -

PDF Library/Candidiasis.Pdf 7 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010

COMMISSION DE LA TRANSPARENCE Avis 2 octobre 2013 FLUCONAZOLE MAJORELLE 150 mg, gélule B/1 (34009 395 173 0 8) Laboratoire MAJORELLE DCI fluconazole Code ATC (2012) J02AC01 (Antimycosiques à usage systémique) Motif de l’examen Inscription Liste(s) Sécurité Sociale (CSS L.162-17) concernée(s) Collectivités (CSP L.5123-2) Indication(s) « Traitement des Candidoses vaginales et périnéales aiguës et concernée(s) récidivantes » HAS - Direction de l'Evaluation Médicale, Economique et de Santé Publique 1/12 Avis 1 modifié le 28 novembre 2014 SMR SMR modéré ASMR ASMR de niveau V Place dans la Le traitement des candidoses vaginales et périnéales aiguës et récidivantes , stratégie peut être local ou systémique. Dans le cas d’un traitement systémique, il thérapeutique s’agit d’un traitement en dose unique. HAS - Direction de l'Evaluation Médicale, Economique et de Santé Publique 2/12 Avis 1 modifié le 28 novembre 2014 01 INFORMATIONS ADMINISTRATIVES ET REGLEMENTAIRES AMM 24/07/2009 (procédure nationale) Conditions de prescription et de Liste I délivrance / statut particulier 2012 J Anti-infectieux généraux à usage systémique J02 Antimycosiques à usage systémique Classification ATC J02A Antimycosiques à usage systémique J02AC Dérivés triazolés J02AC01 Fluconazole 02 CONTEXTE Il s’agit d’une demande d’inscription de la spécialité FLUCONAZOLE MAJORELLE 150 mg en gélule, sur la liste des spécialités remboursables aux assurés sociaux et sur la liste des médicaments agrées à l’usage des collectivités. FLUCONAZOLE MAJORELLE 150 mg est un générique de la spécialité princeps FLUCONAZOLE PFIZER 150 mg. Il existe deux autres spécialités génériques, BEAGYNE 150 mg et FLUCONAZOLE SANDOZ 150 mg. -

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01 -

EUROPEAN PHARMACOPOEIA 10.0 Index 1. General Notices

EUROPEAN PHARMACOPOEIA 10.0 Index 1. General notices......................................................................... 3 2.2.66. Detection and measurement of radioactivity........... 119 2.1. Apparatus ............................................................................. 15 2.2.7. Optical rotation................................................................ 26 2.1.1. Droppers ........................................................................... 15 2.2.8. Viscosity ............................................................................ 27 2.1.2. Comparative table of porosity of sintered-glass filters.. 15 2.2.9. Capillary viscometer method ......................................... 27 2.1.3. Ultraviolet ray lamps for analytical purposes............... 15 2.3. Identification...................................................................... 129 2.1.4. Sieves ................................................................................. 16 2.3.1. Identification reactions of ions and functional 2.1.5. Tubes for comparative tests ............................................ 17 groups ...................................................................................... 129 2.1.6. Gas detector tubes............................................................ 17 2.3.2. Identification of fatty oils by thin-layer 2.2. Physical and physico-chemical methods.......................... 21 chromatography...................................................................... 132 2.2.1. Clarity and degree of opalescence of -

(Oral and Vaginal) Therapy for Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: a Systematic Review Protocol

Open access Protocol BMJ Open: first published as 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027489 on 22 May 2019. Downloaded from Antifungal (oral and vaginal) therapy for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: a systematic review protocol Juliana Lírio,1 Paulo Cesar Giraldo,2 Rose Luce Amaral,2 Ayane Cristine Alves Sarmento,3 Ana Paula Ferreira Costa,3 Ana Katherine Gonçalves3 To cite: Lírio J, Giraldo PC, ABSTRACT Strengths and limitations of this study Amaral RL, et al. Antifungal Introduction Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is frequent (oral and vaginal) therapy in women worldwide and usually responds rapidly to for recurrent vulvovaginal ► Two independent reviewers will select studies, ex- topical or oral antifungal therapy. However, some women candidiasis: a systematic tract data without different variables and assess develop recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC), which review protocol. BMJ Open the risk of bias, to indicate through evidence-based 2019;9:e027489. doi:10.1136/ is arbitrarily defined as four or more episodes every medicine if there is a more effective antifungal ther- bmjopen-2018-027489 year. RVVC is a debilitating, long-term condition that can apeutic regimen for the treatment of recurrent vul- severely affect the quality of life of women. Most VVC is Prepublication history for vovaginal candidiasis. ► diagnosed and treated empirically and women frequently this paper is available online. ► There may be a limitation of outcome from treat- To view these files, please visit self-treat with over-the-counter medications that could ment variation, routes of administration, different the journal online (http:// dx. doi. contribute to an increase in the antifungal resistance. The doses and quality of the randomised trials used in org/ 10. -

Gardnerella Vaginalis: Characteristics, Clinical Considerations, and Controversies B

CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY REVIEWS, July 1992, p. 213-237 Vol. 5, No. 3 0893-8512/92/030213-25$02.00/0 Copyright 1992, American Society for Microbiology Gardnerella vaginalis: Characteristics, Clinical Considerations, and Controversies B. WESLEY CATLINt Department ofMicrobiology, The Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53226 INTRODUCTION .................................................................. .214 IDENTIFICATION AND CHARACTERISTICS OF G. VAGINALIS ....... 0........... *** ...... 00 .............. *..214 Appearance of Cells and Colonies........................................... ........ 000 ........ 000 ........... 0.0 .........0.214 1%.9 1- Isolation Methods................................................................ ............... oo ........................ *..* ...215 Differential Tests................................................................. ..216 It . Presumptive identification.................................................. I.............................. .. 1lo ^.,1IA Confirmation................%.,%FARRAR 21143IMPRA . o . 0 o 0 . o . o o o o 0 o........... ............. 00.00 ....................................................__________ _ _ klosn Confusing catalase-negative bacteria........ .216 Methods: some yield inconsistent results... .217 1% s _ Other characteristics............................ ......... ......o. ... .2177 Rapid detection................................... .2:,17 Structure, Composition, and Toxic Products ;... ****O..* ....... 0.000.0 .................*.................................z'17 -

PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to the HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2008) (Rev

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2008) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2008) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM GADOCOLETICUM 280776-87-6 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACAMPROSATE -

Profile Uses and Administration Adverse Effects and Precautions

578 Antifun als Ecomi; Econitet; Ecosonet; Ecozol; Heads Shampoot; Hung. : and at least 14 days after resolution of symptoms for Gyno-Pevaryl; Pevaryl; India: Ecanol; Irl.: Ecostatint; Gyno AdverseEffects and Precautions oesophageal infections; doses of up to 400 mg daily may be Pevaryl; Israel: Gyno-Pevaryl; Pevarylt; Ita!. : Dermazolt; Eco Burning and itching have been reported after the used for oesophageal candidiasis if necessary. dergin; Ecomesol; Ecomi; Ecorex; Ecosteril; Ganazolo; Ifenec; application of fenticonazole nitrate. Fluconazole 150 mg as a single oral dose may be used for Micos; Pevaryl; Polinazolo; Malaysia: Gyno-Pevaryl; Mex.: Are Intravaginal preparations of fenticonazole may damage genital candidiasis (vaginal candidiasis or candida! colex; Micostyl; Pevaryl; Neth.: Pevaryl; Norw.: Pevaryl; NZ: latex contraceptives and additional contraceptive measures balanitis). Ecremet; Pevaryl; Philipp.: Pevaryl; Pol.: Gyno-Pevaryl; are therefore necessary during local application. Dermatophytosis, pityriasis versicolor, and Candida Pevaryl; Pevazol; Port.: Gyno-Pevaryl; Pevaryl; Rus.: Ecalin For a discussion of the caution needed when using azole infections of the skin may be treated with fluconazole (3KliJ1HH)t; Ecodax (3KOAa.Kc); Gyno-Pevaryl (fmm-IleBapHJI); antifungals during pregnancy, see under Pregnancy in lienee (HijleHex); S.Afr.: Ecodermt; Econal-Ct; Gyno-Pevaryl; 50 mg orally once daily for up to 6 weeks. Precautions of Fluconazole, p. 579.3. Pevaryl; Singapore: Gyno-Pevaryl; Pevaryl; Spain: Ecotam; Systemic candidiasis, cryptococcal meningitis, and Micoespect; Swed.: Pevaryl; Switz.: Gyno-Pevaryl; Pevaryl; other cryptococcal infections may be treated with Thai.: Econ; UK: Ecostatint; Gyno-Pevaryl; Pevaryl; Ukr.: Eco· Antimicrobial Action fluconazole orally or by intravenous infusion; the initial dax (EKOAa.Kc); USA: Ecoza; Spectazole; Venez.: Gyno-Pevaryl; dose is 400 mg followed by a maintenance dose of 200 to Fenticonazole is an imidazole antifungal active against a Miconax; Pevaryl. -

Fenticonazole: an Effective Topical Treatment for Superficial Mycoses As the First-Step of Antifungal Stewardship Program

European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2017; 21: 2749-2756 Fenticonazole: an effective topical treatment for superficial mycoses as the first-step of antifungal stewardship program F. TUMIETTO1, L. GIACOMELLI2 1Infectious Diseases Unit Teaching Hospital S. Orsola-Malpighi, Alma Mater Studiorum University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy 2Department of Surgical Sciences and Integrated Diagnostics, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy Abstract. – The resistance of microorgan- infections are defined as infections in which the isms to antimicrobial drugs is a major issue for pathogen is confined to the superficial layer, with public health, with important consequences in minimal or no histological signs1. terms of morbidity, mortality and resource use. The dermatophyte or ringworm infections, su- The phenomenon is so serious that in some ar- eas of the world resistant strains to all available perficial candidosis of the mouth, skin or genital drugs have been selected. tract and infections due to Malassezia, such as Many conditions may result in the development Pityriasis versicolor, are the main conditions. Tin- of resistance: they include the indiscriminate or ea affects external areas of the body. Candidiasis is inappropriate (e.g., for viral infection or coloniza- caused most often by the yeast Candida albicans, tion) use of antibiotics, the excessive duration of although in recent years, cases due to non-albicans the prescribed treatment regimens, as well as in- adequate dosing or administration routes. strains are increasing significantly. Candidiasis of- Resistance is well-known, but less studied, al- ten affects the genitals or inside of the mouth. so for infections caused by fungi. All these infections are usually diagnosed clin- In the last decade, an impressive outbreak ically. -

(S)-N-Methylnaltrexone

(19) & (11) EP 2 450 360 A2 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 09.05.2012 Bulletin 2012/19 C07D 489/08 (2006.01) A61K 31/485 (2006.01) A61P 1/12 (2006.01) A61P 25/04 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 11180242.7 (22) Date of filing: 25.05.2006 (84) Designated Contracting States: • Sanghvi, Suketu. P AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR Kendall Park, NJ New Jersey 18824 (US) HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC NL PL PT RO SE SI • Boyd, Thomas. A SK TR Grandview, NY New York 10960 (US) • Verbicky, Christopher (30) Priority: 25.05.2005 US 684570 P Broadalbin, NY New York 12025 (US) • Andruski, Stephen (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in Clifton Park, NY New York 12065 (US) accordance with Art. 76 EPC: 06771162.2 / 1 928 882 (74) Representative: Jump, Timothy John Simon et al Venner Shipley LLP (71) Applicant: Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 200 Aldersgate Tarrytown, NY 10591 (US) London EC1A 4HD (GB) (72) Inventors: • Wagoner, Howard Warwick, NY New York 10990 (US) (54) (S)-N-Methylnaltrexone (57) This invention relates to S-MNTX, methods of producing S-MNTX, pharmaceutical preparations comprising S- MNTX and methods for their use. EP 2 450 360 A2 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 2 450 360 A2 Description FIELD OF THE INVENTION 5 [0001] This invention relates to (S)-N-methylnaltrexone (S-MNTX), stereoselective synthetic methods for the prepa- ration of S-MNTX, pharmaceutical preparations comprising S-MNTX and methods for their use.