A History of People with Disabilities in Northwest Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Media Coverage of Oil Sands Pipelines: a Chronological Record of Headlines from 2010 to 2014

Media Coverage of Oil Sands Pipelines: A Chronological Record of Headlines from 2010 to 2014 Oil Sands Research and Information Network School of Energy and the Environment University of Alberta December 2014 Oil Sands Research and Information Network The Oil Sands Research and Information Network (OSRIN) is a university-based, independent organization that compiles, interprets and analyses available knowledge about managing the environmental impacts to landscapes and water affected by oil sands mining and gets that knowledge into the hands of those who can use it to drive breakthrough improvements in regulations and practices. OSRIN is a project of the University of Alberta’s School of Energy and the Environment (SEE). OSRIN was launched with a start-up grant of $4.5 million from Alberta Environment and a $250,000 grant from the Canada School of Energy and Environment Ltd. OSRIN provides: Governments with the independent, objective, and credible information and analysis required to put appropriate regulatory and policy frameworks in place Media, opinion leaders and the general public with the facts about oil sands development, its environmental and social impacts, and landscape/water reclamation activities – so that public dialogue and policy is informed by solid evidence Industry with ready access to an integrated view of research that will help them make and execute environmental management plans – a view that crosses disciplines and organizational boundaries OSRIN recognizes that much research has been done in these areas by a variety of players over 40 years of oil sands development. OSRIN synthesizes this collective knowledge and presents it in a form that allows others to use it to solve pressing problems. -

Tell Cookie Tree Recipes in Book It's Showdown Time for Cass City And

SECTION ONE SECTION ONE Pages 1 to 8 Pages 1 to 8 THIS ISSUE THIS ISSUE VOLUME 53, NUMBER 29 • ITY. MICHIGAN THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 1959 TWELVE PAGES Available Locally 50 Hear Souder Hospital One-Third Tell Cookie Tree Speak at Lions Ladies' Night Completed-Hudson Recipes in Book Work on the new Cass City JL Community hospital is about a Many area residents will recall An estimated 50 Lions and their third completed, Oran Hudson, when an article telling of the un- wives were entertained Monday hospital administrator, an- From the iisual Christmas cookie tree of 1 night at Bush's Restaurant by nounced this week. Mrs. Louis LaGorce, mother of Paul Souder, vice-president of The mechanical and plumbing Drive-to Start Mrs. H. 0. Paul of Cass City, ap- the Michigan National Bank in work is about 40 per cent com- ditor's Corner peared in the National Geographic S'aginaw. pleted. The general contractor E magazine ... it was this article Mr. Souder, a delegate to Rus- estimates that about 32 per cent Today in County that touched off a wave of in- sia in connection with the foreign of his work is done and the elec- It was a quiet Halloween in terest in the project that has re- Cass City Saturday. Chief Bill exchange banking program spon- trical work is about 17 per cent sulted in a book about the pYoject sored by the government, showed Wood reports not one case of that was to have been released completed. The work of the ar- The annual Christian 'Rural vandalism in the community and this week. -

EDITORIAL Screenwriters James Schamus, Michael France and John Turman CA 90049 (310) 447-2080 Were Thinking Is Unclear

screenwritersmonthly.com | Screenwriter’s Monthly Give ‘em some credit! Johnny Depp's performance as Captain Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl is amazing. As film critic after film critic stumbled over Screenwriter’s Monthly can be found themselves to call his performance everything from "original" to at the following fine locations: "eccentric," they forgot one thing: the screenwriters, Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, who did one heck of a job creating Sparrow on paper first. Sure, some critics mentioned the writers when they declared the film "cliché" and attacked it. Since the previous Walt Disney Los Angeles film based on one of its theme park attractions was the unbear- able The Country Bears, Pirates of the Caribbean is surprisingly Above The Fold 370 N. Fairfax Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90036 entertaining. But let’s face it. This wasn't intended to be serious (323) 935-8525 filmmaking. Not much is anymore in Hollywood. Recently the USA Today ran an article asking, basically, “What’s wrong with Hollywood?” Blockbusters are failing because Above The Fold 1257 3rd St. Promenade Santa Monica, CA attendance is down 3.3% from last year. It’s anyone’s guess why 90401 (310) 393-2690 this is happening, and frankly, it doesn’t matter, because next year the industry will be back in full force with the same schlep of Above The Fold 226 N. Larchmont Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90004 sequels, comic book heroes and mindless action-adventure (323) 464-NEWS extravaganzas. But maybe if we turn our backs to Hollywood’s fast food service, they will serve us something different. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. January 5, 2015 to Sun. January 11, 2015 Monday January 5, 2015 Tuesday January 6, 2015

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. January 5, 2015 to Sun. January 11, 2015 Monday January 5, 2015 5:30 PM ET / 2:30 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Gene Simmons Family Jewels Baltic Coasts Face Your Demons - While on tour in Amsterdam, Gene and Shannon spend some quality time The Bird Route - Every spring and autumn, thousands of migrating birds over the Western with a young fan writing a school report. Pomeranian bodden landscape deliver one of the most breathtaking nature spectacles. 6:30 PM ET / 3:30 PM PT 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Gene Simmons Family Jewels Smart Travels Europe What Happens In Vegas... - Gene and Shannon get invited to the premiere of the new Cirque du Out of Rome - We leave the eternal city behind by way of the famous Apian Way to explore the Soleil show “Viva Elvis” in Las Vegas. environs of Rome. First it’s the majesty of Emperor Hadrian’s villa and lakes of the Alban Hills. Next, it’s south to the ancient seaport of Ostia, Rome’s Pompeii. Along the way we sample olive 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT oil, stop at the ancient’s favorite beach and visit a medieval hilltop town. Our own five star villa Gene Simmons Family Jewels is a retreat fit for an emperor. God Of Thund - An exhausted Shannon reaches her limit with Gene’s snoring and sends him packing to a sleep doctor. 9:30 AM ET / 6:30 AM PT The Big Interview Premiere Alan Alda - Hollywood’s Mr. -

Sxsw Film Festival Announces 2018 Features and Opening Night Film a Quiet Place

SXSW FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 2018 FEATURES AND OPENING NIGHT FILM A QUIET PLACE Film Festival Celebrates 25th Edition Austin, Texas, January 31, 2018 – The South by Southwest® (SXSW®) Conference and Festivals announced the features lineup and opening night film for the 25th edition of the Film Festival, running March 9-18, 2018 in Austin, Texas. The acclaimed program draws thousands of fans, filmmakers, press, and industry leaders every year to immerse themselves in the most innovative, smart and entertaining new films of the year. During the nine days of SXSW 132 features will be shown, with additional titles yet to be announced. The full lineup will include 44 films from first-time filmmakers, 86 World Premieres, 11 North American Premieres and 5 U.S. Premieres. These films were selected from 2,458 feature-length film submissions, with a total of 8,160 films submitted this year. “2018 marks the 25th edition of the SXSW Film Festival and my tenth year at the helm. As we look back on the body of work of talent discovered, careers launched and wonderful films we’ve enjoyed, we couldn’t be more excited about the future,” said Janet Pierson, Director of Film. “This year’s slate, while peppered with works from many of our alumni, remains focused on new voices, new directors and a range of films that entertain and enlighten.” “We are particularly pleased to present John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place as our Opening Night Film,” Pierson added.“Not only do we love its originality, suspense and amazing cast, we love seeing artists stretch and explore. -

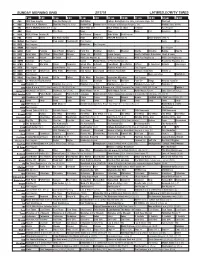

Sunday Morning Grid 2/17/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/17/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding College Basketball Ohio State at Michigan State. (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Hockey Day Hockey New York Rangers at Pittsburgh Penguins. (N) Hockey: Blues at Wild 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid American Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Planet Weird Fox News Sunday News PBC Face NASCAR RaceDay (N) 2019 Daytona 500 (N) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Grand Canyon Huell’s California Adventures: Huell & Louie 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Jeffress Win Walk Prince Carpenter Intend Min. -

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level

Accelerated Reader Book List Report by Reading Level Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27212EN The Lion and the Mouse Beverley Randell 1.0 0.5 330EN Nate the Great Marjorie Sharmat 1.1 1.0 6648EN Sheep in a Jeep Nancy Shaw 1.1 0.5 9338EN Shine, Sun! Carol Greene 1.2 0.5 345EN Sunny-Side Up Patricia Reilly Gi 1.2 1.0 6059EN Clifford the Big Red Dog Norman Bridwell 1.3 0.5 9454EN Farm Noises Jane Miller 1.3 0.5 9314EN Hi, Clouds Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 9318EN Ice Is...Whee! Carol Greene 1.3 0.5 27205EN Mrs. Spider's Beautiful Web Beverley Randell 1.3 0.5 9464EN My Friends Taro Gomi 1.3 0.5 678EN Nate the Great and the Musical N Marjorie Sharmat 1.3 1.0 9467EN Watch Where You Go Sally Noll 1.3 0.5 9306EN Bugs! Patricia McKissack 1.4 0.5 6110EN Curious George and the Pizza Margret Rey 1.4 0.5 6116EN Frog and Toad Are Friends Arnold Lobel 1.4 0.5 9312EN Go-With Words Bonnie Dobkin 1.4 0.5 430EN Nate the Great and the Boring Be Marjorie Sharmat 1.4 1.0 6080EN Old Black Fly Jim Aylesworth 1.4 0.5 9042EN One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Bl Dr. Seuss 1.4 0.5 6136EN Possum Come a-Knockin' Nancy VanLaan 1.4 0.5 6137EN Red Leaf, Yellow Leaf Lois Ehlert 1.4 0.5 9340EN Snow Joe Carol Greene 1.4 0.5 9342EN Spiders and Webs Carolyn Lunn 1.4 0.5 9564EN Best Friends Wear Pink Tutus Sheri Brownrigg 1.5 0.5 9305EN Bonk! Goes the Ball Philippa Stevens 1.5 0.5 408EN Cookies and Crutches Judy Delton 1.5 1.0 9310EN Eat Your Peas, Louise! Pegeen Snow 1.5 0.5 6114EN Fievel's Big Showdown Gail Herman 1.5 0.5 6119EN Henry and Mudge and the Happy Ca Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9477EN Henry and Mudge and the Wild Win Cynthia Rylant 1.5 0.5 9023EN Hop on Pop Dr. -

Big Game in the Big Easy Delicious Boys Hoops Girls Hoops

Video: Irate Man Attacks Paramedics; Police Say Fight Was Unprovoked / Main 5 $1 Big Game in the Big Easy Bring the Taste of the Delta to Your Super Bowl Meal / Life: Food Early Week Edition Tuesday, Jan. 29, 2013 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com W.F. West’s Science Blazer Basketball Programs Earn Statewide Praise Girls Hoops Lady Blazers Destroy Clippers / Grants Sports for Robots Boys Hoops Blazer Men Improve to 6-2 in League Play / Sports Delicious Annual Taste of Lewis County Is See Main 14 a Tour for the Senses / Main 3 Pete Caster / [email protected] Kendra Allen, a senior at W.F. West High School, launches a ping-pong ball with a robot that she and her robotics class partner, Carli Stowe, built for a class project. This program, among others, has earned W.F. West High School the title of a state “Lighthouse School” for science, technology, engineering and mathematics. Allen, who inished her project last week, demonstrated how her robot could pick up a ping-pong ball, move to the launching pad, then shoot the ball six feet. If all of those requirements were met the student would get an ‘A’ on the project. White said about 1/3 of the class completely met the requirements of the project. Winlock Middle School Awarded Funding for Robotics Program Weather TONIGHT: Low Rain Likely see details on page Main 2 43 TOMORROW: Weather picture by Amaya High Espinoza, Onalaska Elementary, 3rd Grade 48 The Chronicle, Serving The Greater Lewis County Area Since 1889 Pete Caster / [email protected] Eighth graders Bradley Follow Us on Twitter Kelly, left, Adam Hylton, center, and Michael @chronline Rosenberry, work at licking plastic balls Find Us on Facebook towards a make-shift www.facebook.com/ goal during their Ro- botics 101 class at Win- thecentraliachronicle lock Middle School on Monday. -

Public Cheers, Confidential Showdown

chapter 5 Public Cheers, Confidential Showdown 5.1 ‘Hit the Pope and You Die’ On 9 January 1938 over sixty archbishops and bishops of Italian dioceses, together with some two thousand parish priests and other clergy, gathered in Rome to be received by Mussolini.1 They were the ecclesiastics who had re- ceived prizes in the almost decade-long activity of the national grain competi- tion, held by the periodical Italia e Fede, under the auspices of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests and the standing committee for grain.2 Gathered in the Aula Magna of the Collegio Romano, they approved an order of the day express- ing gratitude and devotion to the Duce, ‘founder of the Empire’. They then pro- cessed to the Victor Emanuel II Monument to pay homage to the tomb of the Unknown Soldier, to the altar of those who had fallen for the Revolution, and to the memorial of Arnaldo Mussolini on the Campidoglio. At the end of these rites, held in an atmosphere of devotion and prayer, the ecclesiastics entered the Palazzo Venezia (Mussolini’s headquarters) from its main entrance on the Via del Plebiscito, where they were received by a guard of honor, and escorted to the audience hall in the Sala Regia. It was just short of midday: Mussolini – we read in La Stampa – had left them the time, “with delicate thoughtfulness”, to recite a prayer before his arrival.3 When the head of the government finally made his entrance, they greeted him with a standing ovation and, with arms raised in the Roman salute, hailed him with the acclamation: “Duce! Duce! Duce!”. -

Bulloch Herald

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Bulloch County Newspapers (Single Issues) Bulloch County Historical Newspapers 12-10-1959 Bulloch Herald Notes Condition varies. Some pages missing or in poor condition. Originals provided for filming by the publisher. Gift of tS atesboro Herald and the Bulloch County Historical Society. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/bulloch-news- issues Recommended Citation "Bulloch Herald" (1959). Bulloch County Newspapers (Single Issues). 3372. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/bulloch-news-issues/3372 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Bulloch County Historical Newspapers at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulloch County Newspapers (Single Issues) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Denmark News CARD' OF mANKS I wIsh to take thla opportunl· The Bulloch Herald ty to thanks the people ot Bul .. loch tor "·' .. · .. • •·• County supporting me Statesboro, Georgia, Thursday, December 3, 1959 m' ·II.II H.O ... Denmark Home in the Demonstration November 18 primary to 1------------------------ succeed myself as Tax Commls- TO mE VOTERS OF IIcly my .congratulatlons to Mr. sloner of Bulloch County. I BULLOCH COUNTY: Neville tor his victory and to Club at the home of Mrs. R. P. Miller deeply appreclat thl. endose- wish him every success I would like to this during ...... 1'1 16Pageo ment and I the take his term of ........ THE pledge you very office. The campaign i BULLOCH means to express my sincere MRS. H. H. ZETTEROWER best administration of the of- which he was clean nnd '1 ea.. -

Early Morning • Thursday, February 9, 2012 Primetime

February 4, 2012—THE TIMES LEADER—Princeton, Ky. Section C, Page 5 EARLY MORNING • THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2012 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 1:30 2 AM 2:30 3 AM 3:30 4 AM 4:30 5 AM 5:30 6 AM 6:30 7 AM 7:30 8 AM 8:30 WEHT ^ 9 Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. (1:32) ABC World News Now (N) (CC) Morning Eyewitness News Daybreak (N) (CC) Good Morning America (N) (CC) WSIL # # Seinfeld Seinfeld 30 Rock 30 Rock (2:07) TMZ ’Til Death (3:07) ABC World News Now (N) (CC) Morning News 3 This Morning (N) (CC) Good Morning America (N) (CC) WSMV $ $ Late Night Carson Daly (1:05) Today (CC) Late Night /Jimmy Fallon Access H. Early Today Channel 4 News Today (N) Channel 4 News Today Today Donald Trump; The Fray performs. (N) (CC) WTVF % % Late Frasier The Nate Berkus Show Paid Prog. (2:37) Up to the Minute CBS News Report Morning News Morning Report (N) CBS This Morning (N) (CC) WPSD & & Late Night Carson Daly (1:05) Today (CC) Comics Recipe.TV Homeowner Business Early Today Local 6 Today (N) Today Donald Trump; The Fray performs. (N) (CC) WTVW _ _ Tummy Paid Prog. Mission: Impossible Combat! “Reunion” 12 O’Clock High The Nate Berkus Show The People’s Court (N) Paid Prog. Storms News Local 7 News Lifestyles WGN ) Sunny Futurama Futurama South Park South Park ’Til Death ’Til Death Mad Abt. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. J. Meyer Creflo Doll Paid Prog.