The Three Cs Model of Product Placement Effects Cristel Antonia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

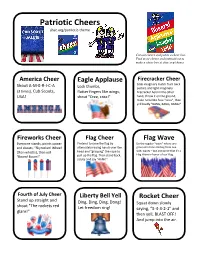

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Home (/gendersarchive1998-2013/) Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock May 1, 2012 • By Linda Mizejewski (/gendersarchive1998-2013/linda-mizejewski) [1] The title of Tina Fey's humorous 2011 memoir, Bossypants, suggests how closely Fey is identified with her Emmy-award winning NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006-), where she is the "boss"—the show's creator, star, head writer, and executive producer. Fey's reputation as a feminist—indeed, as Hollywood's Token Feminist, as some journalists have wryly pointed out—heavily inflects the character she plays, the "bossy" Liz Lemon, whose idealistic feminism is a mainstay of her characterization and of the show's comedy. Fey's comedy has always focused on gender, beginning with her work on Saturday Night Live (SNL) where she became that show's first female head writer in 1999. A year later she moved from behind the scenes to appear in the "Weekend Update" sketches, attracting national attention as a gifted comic with a penchant for zeroing in on women's issues. Fey's connection to feminist politics escalated when she returned to SNL for guest appearances during the presidential campaign of 2008, first in a sketch protesting the sexist media treatment of Hillary Clinton, and more forcefully, in her stunning imitations of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, which launched Fey into national politics and prominence. [2] On 30 Rock, Liz Lemon is the head writer of an NBC comedy much likeSNL, and she is identified as a "third wave feminist" on the pilot episode. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

IT's NOT FUNNY AFTER ALL THEY EARNED THEIR WINGS This Issue

ISSUE 3 S p r i n g This Issue 2 0 2 0 It’s Not Funny Afterall P.1 College Men & Residence Life P.2 You Earned Your Wings P.3 THEY EARNED Making the Grade Went Viral P.4 THEIR WINGS Blue Devil in Orange Tiger Country P.5 The following Differences Between Men and Women P.6 registered participants 5th Annual Dads Matter Too Conference P.7 of the Brotherhood Ropes to Courage P.8 Initiative earned a 3.0 In the Spotlight P.10 or better for the fall Bassett Update P.13 2019 semester (p. 3) Bassett Humanitarian Award Recipient P.14 Mr. Anas Alomari IT’S NOT FUNNY AFTER ALL and/or disparaging them for their gender Miss. Edith Anger by William Fothergill was accepted and seen as humorous. We all Miss. Tara Brooks Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, I laughed, and probably never really thought Mr. Cameron Clark had the opportunity to catch up on my about the power of the hidden message. We Mr. Eric Desmarais television viewing. I am not sure if this was a laughed when Edith Bunker (Jean Stapleton) good or bad thing, but it provided me with was called a “dingbat” by her tv husband Dr. Byron Dickens the opportunity to do what social scientist Archie on the sitcom All in the Family. We all Mr. Mahmoud Elassy loves to do – observe. It only took a few days laughed at Chrissy (Suzanne Somers), on the Mr. Joseph Gohar to remind myself about the biases that exist show Three is Company, when she was depicted as the embodiment of a “dumb in the media. -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

Everybody Loves Raymond” Let’S Shmues--Chat

THANKSGIVING WITH THE CAST OF “EVERYBODY LOVES RAYMOND” LET’S SHMUES--CHAT The Yiddish word for “turkey” is “indik.” “Dankbar” is the Yiddish word for “thankful.” By MARJORIE GOTTLIEB WOLFE 46 “milyon” turkeys are eaten each Thanksgiving. Turkey consumption has increased 104% since 1970. And 88% of Americans surveyed by the National Turkey Federation eat turkey on this holiday. Marie Barone (Doris Roberts) is devoted to making sure her boys are well-fed. She gets her adult children back with food. It’s like a culinary hostage trade-off. Marie wants Debra, her daughter-in-law, to be a better cook. She calls her “cooking-challenged” and thinks that she should live directly opposite Zabar’s. Marie want the children to have better food. She says, “A mother’s love for her sons is a lot like a dog’s piercing bark: protective, loyal, and impossible to ignore. Many episodes of “Everybody Loves Raymond” dealt with Thanksgiving. Grab a #2 pencil and see if you can identify which of the following story lines is real or fabricated. Good luck. EPISODE 1. Thanksgiving has arrived. Marie is on a “diete.” She has just returned from a residential treatment facility for weight (“vog”) loss at Duke University in North Carolina. It was an expensive (“tayer”) program. The lockdown began: Low-Fat, No-Sugar (“tsuker”), No Taste foods, and 750 calories a day. (That’s the equivalent of a slice of chocolate cake.) One woman in the program sent herself “Candygrams” each week (“vokh”). Doris eats very little (“a bisl”) at the Thanksgiving table, but as she is preparing to leave Debra’s house, she asks for a little leftover turkey and apple (“epl”) chutney. -

General Cheers

NWA Kickball Cheers General Cheers Alamo: Kick it high. Kick it low. Kick it to the Alamo. Alamo, here we come. __________ is number one! Hot Dog: __________ wants a hot dog. __________ wants a coke. __________ wants a Home Run, and that's no joke! __________ wants a an orange. __________ wants a shake. __________ wants a to make it to Home Plate! Rock You [ Stomp, stomp, clap. Stomp, stomp, clap. ] We will, we will … Rock you down. Shake you up. Like a volcano ready to erupt. Watch out world. Here we come. __________ is number one! Froggy There was a little froggy -- sitting on a log He rooted for the other team -- it made no sense at all. We pushed him the water, and bonked his little head. And when he came back up again, this is what he said, he said: Go! Go, go! Go, mighty __________ . Fight! Fight, fight! Fight, mighty __________ . Win! Win, win! Win, mighty __________ . Go! Fight! WIn! Beat 'em till the end. Wooo! Big We’re BIG - B. I. G. And we’re BAD - B. A. D. And we’re BOSS - B. O. S. S. - B. O. S. S. - BOSS ! (REPEAT) We Are We are the __________ . Couldn't be prouder. If you can't hear us, we'll yell a little louder. (REPEAT - Louder each time) Stand Up Two bits! Four bits! Six bits! A dollar! All for the __________ stand up and holler! Call & Answer Cheers Dynamite: Our team is WHAT? DYNAMITE! Our team is WHAT? DYNAMITE! Our team is -- Hold on. -

Everybody Loves Raymond

SHOW BIZ Maria Faisal Everybody Loves Raymond Based on the real-life experiences of Ray Romano, Everybody Loves Raymond, the popular sitcom ran from September 1996 to May 2005. Everybody Loves Raymond, a very popular American sitcom broadcast on CBS, ran from 1996 to 2005. The show revolved around the life of Ray Barone, a News Paper sportswriter from Long Island, his wife, Debra, daughter, Ally, and identical twin sons, Geoffrey and Michael. Ray has imposing parents and a jealous, insecure brother, Robert. They are found most of the time in the living room of Ray. Debra, Ray's wife is sick of this routine that had turned her in to a cranky yelling woman, but tolerates for the love of her husband. Ray’s parents and brother never give Ray or his family a moment of peace. Ray often finds himself in the middle of someone else's problems. He is usually the one blamed for everyone else's troubles. Based on the real-life experiences of Ray Romano, Everybody Loves Raymond premiered on September 13, 1996, on CBS. The series finale was broadcast on May 16, 2005, though old episodes are still rerun on cable network TBS and in daily syndication. The show can be watched Monday to Friday on Rogers channel 35, 835, 47 and 847. Paaras 1 Interesting Facts About the Show ·In an unusual turn for such a long-running show, ·Like Robert Barone in Everybody Loves Raymond, every episode featured a single plotline followed Ray Romano has a brother who works for the New throughout both acts. -

Views on Happiness in the Television Series Ally Mcbeal: the Philosophy of David E

QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ McKee, Alan (2004) Views On Happiness In The Television Series Ally Mcbeal: The Philosophy Of David E. Kelley. Journal of Happiness Studies 5(4):pp. 385- 411. © Copyright 2004 Springer The original publication is available at SpringerLink http://www.springerlink.com 1 Views on happiness in the television series Ally McBeal: the philosophy of David E Kelley Alan McKee Film and Television Queensland University of Technology Kelvin Grove QLD 4059 Australia [email protected] 2 Abstract This article contributes to our understanding of popular thinking about happiness by exploring the work of David E Kelley, the creator of the television program Ally McBeal and an important philosopher of happiness. Kelley's major points are as follows. He is more ambivalent than is generally the case in popular philosophy about many of the traditional sources of happiness. In regard to the maxim that money can't buy happiness he gives space to characters who assert that there is a relationship between material comfort and happiness, as well as to those that claim the opposite position. He is similarly ambivalent about the relationship between loving relationships and happiness; and friendships and happiness. In relation to these points Kelley is surprisingly principled in citing the sources that he draws upon in his thinking (through intertextual references to genres and texts that have explored these points before him). His most original and interesting contributions to popular discussions of the nature of happiness are twofold. The first is his suggestion that there is a lot to be said for false consciousness. -

Honors Courses Fall 2017 AM Classic Sitcoms Ing the Civil War

HONORS PROGRAM Honors Astronomy 10 Introduction to Astronomy Would you like to learn the difference inquiry scenarios and special topics. The between dark energy and dark planetarium and the rooftop matter or how to calculate the telescopes will be pressed into number of detectible civiliza- service regularly, and we will or- tions in the Galaxy? If your ganize field trips to the Chabot answer is “yes”, then take this Space and Science Center and class! We will explore the Cos- the Morrison Planetarium. mos with a profusion of TuTh 9:30-10:50AM IGETC Area 5A, CSU Area B1, Honors: Math/Sci Professor Scott Cabral has loved astronomy since as long as he can remember. After getting a B.A. at U.C. Berkeley, he started teaching astronomy at Los Medanos in 1989 while still working on his M.S. at San Francisco State University. Scott is a veteran of countless public planetarium shows and telescope viewing par- ties, besides being the proud owner of over 15,000 astronomy slides. In addition to that, he loves participating in Honors activities, whether it is delivering a bad poem at the Honors Yosemite Retreat, moderating at the Honors Research Symposium, or trekking up Mount Diablo on our annual spring hike. Honors History 30 US History from 1865 From the gay marriage movement to Don- How was this term defined by diverse 19th ald Trump’s anti-government campaign and 20th century groups such as freed platform, what’s happening in African American slaves, Filipino today’s world has its roots in the students in California or women past.