Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 57, Number 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oxford Book Fair List 2014

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD OXFORD BOOK FAIR LIST including NEW ACQUISITIONS ● APRIL 2014 Main Hall, Oxford Brookes University (Headington Hill Campus) Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP Stand 87 Saturday 26th April 12 noon – 6pm - & - Sunday 27th April 10am – 4pm A MEMOIR OF JOHN ADAM, PRESENTED TO THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER LORD GRENVILLE BY WILLIAM ADAM 1. [ADAM, William (editor).] Description and Representation of the Mural Monument, Erected in the Cathedral of Calcutta, by General Subscription, to the Memory of John Adam, Designed and Executed by Richard Westmacott, R.A. [?Edinburgh, ?William Adam, circa 1830]. 4to (262 x 203mm), pp. [4 (blank ll.)], [1]-2 (‘Address of the British Inhabitants of Calcutta, to John Adam, on his Embarking for England in March 1825’), [2 (contents, verso blank)], [2 (blank l.)], [2 (title, verso blank)], [1]-2 (‘Description of the Monument’), [2 (‘Inscription on the Base of the Tomb’, verso blank)], [2 (‘Translation of Claudian’)], [1 (‘Extract of a Letter from … Reginald Heber … to … Charles Williams Wynn’)], [2 (‘Extract from a Sermon of Bishop Heber, Preached at Calcutta on Christmas Day, 1825’)], [1 (blank)]; mounted engraved plate on india by J. Horsburgh after Westmacott, retaining tissue guard; some light spotting, a little heavier on plate; contemporary straight-grained [?Scottish] black morocco [?for Adam for presentation], endpapers watermarked 1829, boards with broad borders of palmette and flower-and-thistle rolls, upper board lettered in blind ‘Monument to John Adam Erected at Calcutta 1827’, turn-ins roll-tooled in blind, mustard-yellow endpapers, all edges gilt; slightly rubbed and scuffed, otherwise very good; provenance: William Wyndham Grenville, Baron Grenville, 3 March 1830 (1759-1834, autograph presentation inscription from William Adam on preliminary blank and tipped-in autograph letter signed from Adam to Grenville, Edinburgh, 6 March 1830, 3pp on a bifolium, addressed on final page). -

11 February 1992.Pdf

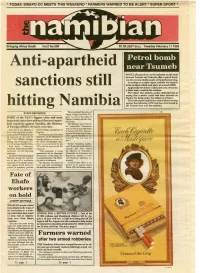

* TODAY: SWAPO CC MEE"FS THIS WEEKEND * FARMERS WARNED TO, BE AlERT * SUPER SPORT * c • Bringing Africa South Vol.2 No.500 R1.00 (GST Inc.) Tuesday February 111992 AIl ti -apartheid REGULAR patrols are to be instituted on the road between Tsumeb and Oshivelo after a petrol bomb was thrown at a minibus early on Saturday morning. , Accor ding to a radio report, nobody was injured sanctions still in the incident which took place at around 02hOO. Apparently two motor cyclists and a car, driven by a white man, overtook the minibus. The report also quoted a police spokesperson as saying that a motor cyclist had been arrested on Sunday for being under the influence of liquor. The radio report said further that leaflets warning against the rightwing A WB had been distributed in hitting Namibia the Tsumeb area over the weekend. These included the states of ~--------~================-, === STAFF REPORTER Maine, Oregon and West Vir - SOME of the USA's biggest cities and most ginia, as well as the cities of Denver, Colorado and Palo Alto, important states have still not lifted anti-apart California. heid sanctions against Namibia, the Ministry The Ministry noted'that af of Foreign Affairs revealed yesterday. ter "constructive" discussions with the Maryland authorities Included in the Ministry's and its illegal occupation of in January this year, the pass list of city and state govern Namibia. ing of a bill removing all sanc ments in the US that have kept The Ministry said one of the tions against Namibia is ex up sanctions are the cities of objectives of the Ministry of ' pected in "the very near fu New York, Miami, Atlanta, Foreign Affairs is to point out ture". -

Engineering Men: Masculinity, the Royal Navy, and The

ENGINEERING MEN: MASCULINITY, THE ROYAL NAVY, AND THE SELBORNE SCHEME by © Edward Dodd A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History Memorial University of Newfoundland October 2015 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador ABSTRACT This thesis uses R.W. Connell’s hegemonic masculinity to critically examine the “Selborne Scheme” of 1902, specifically the changes made to naval engineers in relation to the executive officers of the late-Victorian and Edwardian Royal Navy. Unlike the few historians who have studied the scheme, my research attends to the role of masculinity, and the closely-related social structures of class and race, in the decisions made by Lord Selborne and Admiral John Fisher. I suggest that the reform scheme was heavily influenced by a “cultural imaginary of British masculinity” created in novels, newspapers, and Parliamentary discourse, especially by discontented naval engineers who wanted greater authority and respect within the Royal Navy. The goal of the scheme was to ensure that men commanding the navy were considered to have legitimate authority first and foremost because they were the “best” of British manhood. This goal required the navy to come to terms with rapidly changing naval technology, a renewed emphasis on the importance of the role of the navy in Britain’s empire, and the increasing numbers of non-white seamen in the British merchant marine. Key Words: Masculinity, Royal Navy, Edwardian, Victorian, Naval Engineers, Selborne Scheme, cultural imaginary, British Empire. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to the staff at the National Archives in London who were extremely friendly and helpful, especially Janet Dempsey for showing me around on my first visit. -

University of California Santa Cruz Romance

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ ROMANCE: THE EMULATION OF EMPIRE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LITERATURE by Martha E. Bonilla December 2016 The Dissertation of Martha E. Bonilla is approved: __________________________________ Professor Susan Gillman, chair __________________________________ Professor Kirsten Silva Gruesz __________________________________ Professor Catherine A. John _____________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Martha E. Bonilla 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents………………………………………………………………..iii Abstract………………………………………………………..…………..……..iv Acknowledgement………………………………………………………………..vi Chapter 1 Romance as the Desire for Empire: An Introduction…………………….………..1 Chapter 2 The Tempest, a Romance for a New World of Empire…………………….…..…58 Chapter 3 Remembering to Forget: Desire, Emulation, and Romance in J.F. Cooper’s The Pioneers……………………..…………………….………….113 Chapter 4 Benito Cereno’s Black Letter Text: The Unread Story of Empire……..…..……159 . Chapter 5 The Happy Resolution and the Solace of Amnesia……………..……………..….204 Epilogue The Don of a Pervious Age…….……..………………………………..…………227 Bibliography………………………………………………………….………..….251 iii ABSTRACT Martha E. Bonilla Romance: The Emulation of Empire This dissertation offers a symptomatic reading of romance and explores the ideological force of the genre’s chiastic structure. The trajectory of this project follows the temporal and spatial migration of romance from the colonial context of early seventeenth England, beginning with William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, then enters the American post-revolutionary context of the early and late nineteenth century with James Fennimore Cooper’s The Pioneers, Herman Melville’s “Benito Cereno,” and ends with Maria Amparo Ruiz de Burton’s The Squatter and the Don. This study examines the contradictory narrative desires within romance. -

The Capability of Sailing Warships: Manoeuvrability Sam Willis

The Capability of Sailing Warships: Manoeuvrability Sam Willis Dans cet article, S.B.A. Willis continue à faire son enquête sur le potentiel des navires de guerre à voile en réfléchissant à la question de la manière de manœuvrer. En faisant référence à des sources contemporaines, l'auteur considère les aspects significatifs de la performance d'un navire de guerre à voile que jusqu 'à présent les historiens de la navigation de guerre ont négligés ou ont mal compris. Part 1 of this article warned of the inherent dangers of accepting an easily digestible and simplistic vision of sailing capability and explained in some detail the practicalities of making ground to windward in a sailing warship. An incapacity to make ground to windward was not, however, the only significant characteristic of wind dependence. Unfortunately, very few historians of sailing warfare have considered sailing warship capability beyond the question of windward performance, and there remains much of significance that is not widely known. With our accepted understanding so dominated by the question of windward performance, it has been all too easy to associate negative connotations with the broader question of sailing warship capability. It is, furthermore, a sad fact that the only characteristics of sailing warship capability that are generally understood are those that are based on a superficial comparison with steamships. A steamship has an engine that provides head or sternway and a rudder that controls lateral movement. Maritime historians have repeatedly used this template to understand the sailing ship, simply regarding the sailing rig as the direct equivalent of the engine. -

Dealing with the Past in Northern Ireland

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 26, Issue 4 2002 Article 9 Dealing With the Past in Northern Ireland Christine Bell∗ ∗ Copyright c 2002 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Dealing With the Past in Northern Ireland Christine Bell Abstract This Article “audits” Northern Ireland’s discrete mechanisms for dealing with the past, with a view to exploring the wider transitional justice debates. An assessment of what has been done so far is vital to considering what the goals of addressing the past might be, what future developments are useful or required, and what kind of mechanisms might successfully be employed in achieving those goals. DEALING WITH THE PAST IN NORTHERN IRELAND Christine Bell* INTRODUCTION The term "transitional justice" has increasingly been used to consider how governments in countries emerging from deeply rooted conflict address the legacy of past human rights viola- tions.' While the term has a pedigree dating back to the Nuremburg Tribunals, three contemporary factors have reinvig- orated interest.2 The first factor is the prevalence of negotiated agreements as the preferred way of resolving internal conflicts. Premised on some degree of compromise between those who were engaged militarily in the conflict, these compromises affect whether and how the past is dealt with. As Huyse notes, the wid- est scope for prosecutions arises in the case of an overthrow or "victory" where virtually no political limits on retributive punish- * Professor Bell is the Chair in Public International Law, Transitional Justice Insti- tute, School of Law, University of Ulster, and a former member of the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission. -

The Contractor State and Its Implications, 1659-1815 2012

VU Research Portal Global power, local connections Brandon, P. published in The contractor state and its implications, 1659-1815 2012 document license Unspecified Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Brandon, P. (2012). Global power, local connections: The Dutch admiralties and their supply networks. In S. Solbes Ferri, & R. Harding (Eds.), The contractor state and its implications, 1659-1815 (pp. 57-80). Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 07. Oct. 2021 Richard Harding Sergio Solbes Ferri (Coords.) The Contractor State and Its Implications, 1659-1815 Richard Harding Sergio Solbes Ferri (Coords.) The Contractor State and Its Implications, 1659-1815 CONTRACTOR STATE GROUP 0CSG1 International Congress Las Palmas de Gran Canaria 16th-18th November 2011 The Contractor State and Its Implications, 1659-1815 –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– CONTRACTOR STATE GROUP. -

Napoleon Andrew Roberts Reviewed by Robert Schmidt

Napoleon Andrew Roberts Reviewed by Robert Schmidt About the Author Andrew Roberts is a British author who graduated with honors from Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge and is presently a visiting professor in the War Studies Department at Kings College, London. He has written or edited 19 books which have been translated in 22 languages and appears on radio and television around the world. About the Book There have been many books about Napoleon, but Andrew Roberts’ single-volume biography is the first to make full use of the ongoing French publication of Napoleon’s 33,000 letters. Seemingly leaving no stone unturned, Roberts begins in Corsica in 1769, pointing to Napoleon’s roots on that island—and a resulting fascination with the Roman Empire—as an early indicator of what history might hold for the boy. Napoleon’s upbringing—from his roots, to his penchant for holing up and reading about classic wars, to his education in France, all seemed to point in one direction—and by the time he was 24, he was a French general. Though he would be dead by fifty one, it was only the beginning of what he would accomplish. Although Napoleon: A Life is 800 pages long, it is both enjoyable and illuminating. Napoleon comes across as whip smart, well-studied, ambitious to a fault, a little awkward, and perhaps most importantly, a man who could turn on the charm when he needed to. Through his portrait, Roberts seems to be arguing two things: that Napoleon was far more than just a complex soldier, and that his contributions to the world greatly surpassed those of the evil dictators that some compare him to. -

ED 194 419 EDRS PRICE Jessup, John E., Jr.: Coakley, Robert W. A

r r DOCUMENT RESUME ED 194 419 SO 012 941 - AUTHOR Jessup, John E., Jr.: Coakley, Robert W. TITLE A Guide to the Study and use of Military History. INSTITUTION Army Center of Military History, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 79 NOTE 497p.: Photographs on pages 331-336 were removed by ERIC due to poor reproducibility. AVAILABLE FROM Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 ($6.50). EDRS PRICE MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *History: military Personnel: *Military Science: *Military Training: Study Guides ABSTRACT This study guide On military history is intended for use with the young officer just entering upon a military career. There are four major sections to the guide. Part one discusses the scope and value of military history, presents a perspective on military history; and examines essentials of a study program. The study of military history has both an educational and a utilitarian value. It allows soldiers to look upon war as a whole and relate its activities to the periods of peace from which it rises and to which it returns. Military history also helps in developing a professional frame of mind and, in the leadership arena, it shows the great importance of character and integrity. In talking about a study program, the guide says that reading biographies of leading soldiers or statesmen is a good way to begin the study of military history. The best way to keep a study program current is to consult some of the many scholarly historical periodicals such as the "American Historical Review" or the "Journal of Modern History." Part two, which comprises almost half the guide, contains a bibliographical essay on military history, including great military historians and philosophers, world military history, and U.S. -

P2 P3 P4 Two Cheers for the Dublin News

• I i i i • I I I I • • • i i I I I I i i i i l I l I i i • i i I I I I i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i • I I I I i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i p2 p3 p4 Two cheers for the Dublin News management, police-style: Troubled images of the conflict: government's overdue start to the The PTA gets renewed on the day a novelist, a journalist and a process of gay legal reform a massive bomb haul is revealed film-maker look at the North • ••>1111111111111111111111111 • 11111111111111111111111111111 • 111111111111111111111111111111 toishMay 1993 • Price 40p OemocPAConnolly Association: campaigning for a united and independenCt Irelan d Most significantly, By The Editor they ruled out the estab- lishment of a devolved assembly as a viable way forward. "We accept that an internal settlement is EVOLUTION not a solution because it obviously does not deal Dof the ad- with all the relationships ministration at the heart of the prob- of the Six lem," Hume and Adams Counties to a agreed. Northern Ireland "We accept that the government at Stormont Irish people as a whole Castle will bring peace havel a right to national with justice no nearer. self-determination. This On that much at least, is the view shared by a Sinn Fein leader Gerry majority of the people on Adams, SDLP leader this island, though not by John Hume and Irish all its people," they un- Taoiseach Albert derlined. -

Ireland Into the Mystic: the Poetic Spirit and Cultural Content of Irish Rock

IRELAND INTO THE MYSTIC: THE POETIC SPIRIT AND CULTURAL CONTENT OF IRISH ROCK MUSIC, 1970-2020 ELENA CANIDO MUIÑO Doctoral Thesis / 2020 Director: David Clark Mitchell PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES AVANZADOS: LENGUA, LITERATURA Y CULTURA Ireland into the Mystic: The Poetic Spirit and Cultural Content of Irish Rock Music, 1970-2020 by Elena Canido Muiño, 2020. INDEX Abstract .......................................................................................................................... viii Resumen .......................................................................................................................... ix Resumo ............................................................................................................................. x 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1.1. Methodology ................................................................................................................. 3 1.1.2. Thesis Structure ............................................................................................................. 5 2. Historical and Theoretical Introduction to Irish Rock ........................................ 9 2.1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2. The Origins of Rock ...................................................................................................... 9 2.1.3. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Westminster Model Navy Defining the Royal Navy, 1660-1749 McLean, Samuel Alexander Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 The Westminster Model Navy: Defining the Royal Navy, 1660-1749 Samuel A. McLean PhD Thesis, Department of War Studies May 4, 2017 ABSTRACT At the Restoration of the English monarchy in 1660, Charles II inherited the existing interregnum navy.