The George Wright Forum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 34 number 3 • 2017 Society News, Notes & Mail • 243 Announcing the Richard West Sellars Fund for the Forum Jennifer Palmer • 245 Letter from Woodstock Values We Hold Dear Rolf Diamant • 247 Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage Rebecca Conard and John H. Sprinkle, Jr., guest editors Dedication•252 Planned Obsolescence: Maintenance of the National Park Service’s History Infrastructure John H. Sprinkle, Jr. • 254 Shining Light on Civil War Battlefield Preservation and Interpretation: From the “Dark Ages” to the Present at Stones River National Battlefield Angela Sirna • 261 Farming in the Sweet Spot: Integrating Interpretation, Preservation, and Food Production at National Parks Cathy Stanton • 275 The Changing Cape: Using History to Engage Coastal Residents in Community Conversations about Climate Change David Glassberg • 285 Interpreting the Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Yosemite National Park’s History Yenyen F. Chan • 299 Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) M. Melia Lane-Kamahele • 308 A Perilous View Shelton Johnson • 315 (continued) Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage (cont’d) Some Challenges of Preserving and Exhibiting the African American Experience: Reflections on Working with the National Park Service and the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site Pero Gaglo Dagbovie • 323 Exploring American Places with the Discovery Journal: A Guide to Co-Creating Meaningful Interpretation Katie Crawford-Lackey and Barbara Little • 335 Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: A 21st-Century Landscape-scale Conservation and Stewardship Framework Deanna Beacham, Suzanne Copping, John Reynolds, and Carolyn Black • 343 A Framework for Understanding Off-trail Trampling Impacts in Mountain Environments Ross Martin and David R. -

The George Wright

THE GEORGE WRIGHT FORUvolume 23 Mnumber 1 * 2006 The ICOMOS-Ename Charter for Cultural Heritage Interpretation Origins Founded in 1980. the George Wright Society is organized for the pur poses of promoting the application of knowledge, fostering communica tion, improving resource management, and providing information to improve public understanding and appreciation of the basic purposes of natural and cultural parks and equivalent reserves. The Society is dedicat ed to the protection, preservation, and management of cultural and natu ral parks and reserves through research and education. Mission The George Wright Society advances the scientific and heritage values of parks and protected areas. The Society promotes professional research and resource stewardship across natural and cultural disciplines, provides avenues of communication, and encourages public policies that embrace these values. Our Goal The Society strives to be the premier organization connecting people, places, knowledge, and ideas to foster excellence in natural and cultural resource management, research, protection, and interpretation in parks and equivalent reserves. Board of Directors DwiGHT T. PlTCMTHLEY, President • Las Cruces, New Mexico ABIGAIL B. MILLER, Vice President • Shelhurne, Vermont JERRY EMORY, Treasurer • Mill Valley, California GILLIAN BOWSER, Secretary • Bryan, Texas REBECCA CONARD • Murfreesboro, Tennessee ROLF DiAMANT • Woodstock, Vermont SUZANNE LEWIS • Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming DAVID J. PARSONS • Florence, Montana STEPHANIE TOOTHMAN • Seattle, Washington WILLIAM H. WALKER,JR. • Herndon, Virginia STEPHEN WOODLEY • Chelsea, Quebec Executive Office DAVID HARMON, Executive Director EMILY DEKKER-FIALA, Conference Coordinator P. O. Box 65 • Hancock, Michigan 49930-0065 USA 1-906-487-9722 • fax 1-906-487-9405 [email protected] • www.georgewright.org The George Wright Society is a member of US/ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites—U.S. -

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 27 number 1 • 2010 Origins Founded in 1980, the George Wright Society is organized for the pur poses of promoting the application of knowledge, fostering communica tion, improving resource management, and providing information to improve public understanding and appreciation of the basic purposes of natural and cultural parks and equivalent reserves. The Society is dedicat ed to the protection, preservation, and management of cultural and natural parks and reserves through research and education. Mission The George Wright Society advances the scientific and heritage values of parks and protected areas. The Society promotes professional research and resource stewardship across natural and cultural disciplines, provides avenues of communication, and encourages public policies that embrace these values. Our Goal The Society strives to he the premier organization connecting people, places, knowledge, and ideas to foster excellence in natural and cultural resource management, research, protection, and interpretation in parks and equivalent reserves. Board of Directors ROLF DIA.MANT, President • Woodstock, Vermont STEPHANIE T(K)"1'1IMAN, Vice President • Seattle, Washington DAVID GKXW.R, Secretary * Three Rivers, California JOHN WAITHAKA, Treasurer * Ottawa, Ontario BRAD BARR • Woods Hole, Massachusetts MELIA LANE-KAMAHELE • Honolulu, Hawaii SUZANNE LEWIS • Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming BRENT A. MITCHELL • Ipswich, Massachusetts FRANK J. PRIZNAR • Gaithershnrg, Maryland JAN W. VAN WAGTENDONK • El Portal, California ROBERT A. WINFREE • Anchorage, Alaska Graduate Student Representative to the Board REBECCA E. STANFIELD MCCOWN • Burlington, Vermont Executive Office DAVID HARMON,Executive Director EMILY DEKKER-FIALA, Conference Coordinator P. O. Box 65 • Hancock, Michigan 49930-0065 USA 1-906-487-9722 • infoldgeorgewright.org • www.georgewright.org Tfie George Wright Forum REBECCA CONARD & DAVID HARMON, Editors © 2010 The George Wright Society, Inc. -

2016 Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL PARK FOUNDATION 1 Olympic National Park OUR MISSION The National Park Foundation, in partnership with the National Park Service, enriches America’s national parks and programs through private support, safeguarding our heritage, and inspiring future generations of national park enthusiasts. OUR LEADERSHIP (OCTOBER , TO SEPTEMBER , ) PRESIDENT & CEO Will Shafroth The plurality of stories preserved within our national parks BOARD OF DIRECTORS tell of a land molded over millennia, the lives of ancient The Honorable Sally Jewell CHAIR civilizations, the forging of a new nation and the people Al Baldwin VICE CHAIR who helped shape it. They are more than the beloved iconic Jonathan B. Jarvis landscapes in the west – they encompass our history during SECRETARY Brien M. O’Brien chapters of struggle and triumph, preserving the resources TREASURER that define who we are as a people and where we have been. Ellen S. Alberding Rhoda Altom For the past 100 years, the National Park Service has served The Honorable Elizabeth Frawley Bagley as the nation’s storyteller and the caretaker of our natural, Austin Beutner cultural, and historical inheritance. Such a monumental Kathleen Brown Karen Swett Conway undertaking was born from, and enhanced by, public-private Tom Goss partnerships – a legacy that the National Park Foundation Stephen L. Hightower carries forth today. Peter Knight Orin S. Kramer Ellen R. Malcolm Established nearly 50 years ago as the official charity of Henry R. Muñoz, III America’s national parks, we support parks and programs John L. Nau, III through private philanthropy, safeguarding our national Roxanne Quimby Robert S. -

Bennett Bean Playing by His Rules by Karen S

March 1998 1 2 CERAMICS MONTHLY March 1998 Volume 46 Number 3 Wheel-thrown stoneware forms by Toshiko Takaezu at the American Craft FEATURES Inlaid-slip-decorated Museum in vessel by Eileen New York City. 37 Form and Energy Goldenberg. 37 The Work of Toshiko Takaezu by Tony Dubis Merino 75 39 George Wright Oregon Potters’ Friend and Inventor Extraordinaire by Janet Buskirk 43 Bennett Bean Playing by His Rules by Karen S. Chambers with Making a Bean Pot 47 The Perfect Clay Body? by JejfZamek A guide to formulating clay bodies 49 A Conversation with Phil and Terri Mayhew by Ann Wells Cone 16 functional porcelain Intellectually driven work by William Parry. 54 Collecting Maniaby Thomas G. Turnquist A personal look at the joy pots can bring 63 57 Ordering Chaos by Dannon Rhudy Innovative handbuilding with textured slabs with The Process "Hair of the Dog" clay 63 William Parry maker George Wright. The Medium Is Insistent by Richard Zakin 39 67 David Atamanchuk by Joel Perron Work by a Canadian artist grounded in Japanese style 70 Clayarters International by CarolJ. Ratliff Online discussion group shows marketing sawy 75 Inspirations by Eileen P. Goldenberg Basket built from textured Diverse sources spark creativity slabs by Dannon Rhudy. The cover: New Jersey 108 Suggestive Symbols by David Benge 57 artist Bennett Bean; see Eclectic images on slip-cast, press-molded sculpture page 43. March 1998 3 UP FRONT 12 The Senator Throws a Party by Nan Krutchkoff Dinnerware commissioned from Seattle ceramist Carol Gouthro 12 Billy Ray Hussey EditorRuth -

Fall 2009 Arrowhead Newsletter

Arrowhead • Fall 2009 1 Arrowhead Fall 2009 • Vol. 16 • No. 4 The Newsletter of the Employees & Alumni Association of the National Park Service Published By Eastern National FROM THE DIRECTOR Port Chicago Naval Magazine s I write this A column, my first as National N MEM Added to Park System Park Service direc- tor, I am remember- he National Park System has gained cisco, hurled debris in the air, obliterat- resume loading ships for the war effort. ing my confirmation ed both ships and killed everyone at the just a few weeks Ta new park: Port Chicago Naval Many refused to continue their work ago. Although I Magazine National Memorial in Con- waterfront. To this day, because of the without safety training, and the U.S. accepted this re- cord, Calif. With President Obama’s tragedy, ignition sources for bombs and Navy charged 50 of these men with sponsibility humbled by its impor- signing of the Defense Authorization guns are loaded separately on carriers. “conspiring to make mutiny.” They tance and excited about the Act, on Oct. 28 Port Chicago became The disaster caused the greatest loss of were tried, convicted and imprisoned. possibilities, something happened the 392nd unit of a system fondly life on the home front during World War After the war, they were released, grant- that has happened countless referred to as “America’s best idea.” II. Three-hundred-twenty men died, and ed clemency, allowed to complete their times throughout my career—when “The addition of Port Chicago demon- almost 400 others were injured. Of the military service and given honorable dis- I thought it couldn’t get any strates a commitment to make America’s 320 killed, 202 were African Americans. -

I CRANFORD I GARWOOD IOO2 3 NEW ORANGE Jjj DIRECTORY T

Price 15 Cents V AU>ENE V I CRANFORD I GARWOOD IOO2 3 NEW ORANGE jjj DIRECTORY t Published by the CRANFORD CHRONICLE John Kean Julian H. Kcan James Mag^iire President V. President Cashier CHARTERED 1812 National State Bank Of Elizabeth Capital - #350,000 Surplus - $600,000 SAFE DEPOSIT VAULT Absolute Security for Valuables of Every Description. Safes to Rent at $5 per Annum 68 BROAD STREET, EU3ABETH, N. J. y • Accounts Solicited Elizabeth—Plainfleld trolley care transfer to the door. A Street, House and Business RECTORY : OF : ^R AN FORD, Garwood, Aldene and New Orange. Published by the Cranford Chronicle. PUBLICATION OFFICE OF THE CRANFORD CHRONICLE, AND CRANFORD DIRECTORY. STHIS PUBLICATION is the second in what is intended to be a series of annual directories of Cranford and its suburbs—Garwood, Aldene and New Orange. The field covered is growing so rapidly and changes of residence are so frequent that yearly revisions are needed to keep the directory up to date. In sending out the present issue, the CHRONICLE desires to acknowledge the assistance received from local and out of town advertisers. Their patronage permits the sale of the directory at a merely nominal price, and places it within the means of every household. THB CRANFORD CHRONICLE. CRANFORD, N. J., October, 1902. 6 ROSEDALE AND LINDEN PARK CEMETERIES, LINDEN, N. J. J h Over 200 Acres. Beautiful and Accessible, on Main Line Pennsylvania Railroad, 14 Miles from New York. Largest and best equipped cemetery lodge in the country. 6 Transportation and carriages free to take prospective lot buyers over the properties. -

157Th Meeting of the National Park System Advisory Board November 4-5, 2015

NORTHEAST REGION Boston National Historical Park 157th Meeting Citizen advisors chartered by Congress to help the National Park Service care for special places saved by the American people so that all may experience our heritage. November 4-5, 2015 • Boston National Historical Park • Boston, Massachusetts Meeting of November 4-5, 2015 FEDERAL REGISTER MEETING NOTICE AGENDA MINUTES Meeting of May 6-7, 2015 REPORT OF THE SCIENCE COMMITTEE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE URBAN AGENDA REPORT ON THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC VALUATION STUDY OVERVIEW OF NATIONAL PARK SERVICE ACTIONS ON ADVISORY BOARD RECOMMENDATIONS • Planning for a Future National Park System • Strengthening NPS Science and Resource Stewardship • Recommending National Natural Landmarks • Recommending National Historic Landmarks • Asian American Pacific Islander, Latino and LGBT Heritage Initiatives • Expanding Collaboration in Education • Encouraging New Philanthropic Partnerships • Developing Leadership and Nurturing Innovation • Supporting the National Park Service Centennial Campaign REPORT OF THE NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS COMMITTEE PLANNING A BOARD SUMMARY REPORT MEETING SITE—Boston National Historical Park, Commandant’s House, Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston, MA 02139 617-242-5611 LODGING SITE—Hyatt Regency Cambridge, 575 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, MA 62139 617-492-1234 / Fax 617-491-6906 Travel to Boston, Massachusetts, on Tuesday, November 3, 2015 Hotel Check in 4:00 pm Check out 12:00 noon Hotel Restaurant: Zephyr on the Charles / Breakfast 6:30-11:00 am / Lunch 11:00 am - 5:00 pm / Dinner 5-11:00 pm Room Service: Breakfast 6:00 am - 11:00 am / Dinner 5:00 pm - 11:00 pm Wednesday NOVEMBER 4 NOTE—Meeting attire is business. The tour will involve some walking and climbing stairs. -

The Last Word in Airfields a Special History Study Ofcrissy Field Presidio Ofsan Francisco, California

The Last Word in Airfields A Special History Study ofCrissy Field Presidio ofSan Francisco, California by Stephen A. Haller Park Historian Golden Gate National Recreation Area San Francisco National Park Service 1994 Table ofContents Management Summary ................................III Site History .......................................... 1 Project Background .................................... .IV Chapter 1: In the beginning .............................. 1 Historical Context . .................................... .IV Chapter 2: An Airfield is Established, 1919-1922 ............. 11 Site History Summary ...................................V Chapter 3: Early Operations, 1922-1924 ...................29 Study Boundaries ..................................... .IX Chapter 4: Of Races and Runways, 1924-1934. ............. 51 Methodology and Scope . ..................................X Chapter 5: Winding Down, 1935-1940 ....................79 Administrative Context. .................................x Chapter 6: War and Post-War, 1941-1993 ...................S9 Summary ofFindings ....................................X Significance and Integrity Assessment .................. 103 Recommendations .................................... 10S Acknowledgements ................................... 112 Bibliography ........................................ 114 Appendices A Commanding Officers, Crissy Field ...................... 116 B Types of Aircraft at Crissy Field ......................... IIS C Roster of Fourth Army Intelligence School. ............... -

National Parks and a Government Started Agency Devoted Exclusively to Overseeing Them

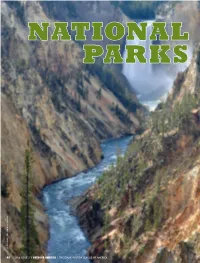

NATIONAL PARKS JACK BALLARD; LISA DENSMORE BALLARD 40 | 2016 ISSUE 2 | OUTDOOR AMERICA | THE IZAAK WALTON LEAGUE OF AMERICA More To See Than BY LISA DENSMORE BALLARD Simply Iconic Views Though steep, the descent into Seven-Mile Hole was worth the thigh burn — as much for its eye-popping views as for the lure of the cutthroats below. The trail snaked alongside a precipice, then dropped to the Yellowstone River. Far below the clifftops, the river rushed away from Yellowstone’s massive Upper and Lower Falls, squeezed between walls of sulfur- stained sandstone and ancient volcanic spires. Boiling water trickled from small, steaming geothermal cracks along the route, which hikers sometimes shared with bears, eagles, and other wildlife looking for a fish dinner. I paused frequently on our way to “the hole” to admire and contemplate the grandeur of the setting. My son was more interested in the trout. Yellowstone cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii bouvieri) are the only native trout in Yellowstone National Park. Once the primary fish species in the region (and an important y son Parker’s grin lit up the narrow food source for 20 bird and mammal species), canyon. After just four casts, a Yellowstone cutthroats were in trouble by the M16-inch Yellowstone cutthroat wriggled impa- 1980s, the victims of drought, over-fishing, tiently at the end of his line. It was the first loss of habitat, whirling disease, hybridization cutthroat trout he had ever caught. The fish with rainbow trout, and competition with and was beautiful: gold and green under its large predation by nonnative fish such as lake trout. -

Integrating Cultural Resources and Wilderness Character

INVITED FEATURES 29 Integrating cultural resources and USFS/PETER LANDRES wilderness character By Jill Cowley, Peter Landres, Melissa Memory, Doug Scott, and Adrienne Lindholm CULTURAL RESOURCES ARE AN INTEGRAL PART OF WILDER- Figure 1. (Above) Ancestral ness and wilderness character. Not all those involved in the pres- Puebloan cliff dwellings in Johns Canyon, Grand Gulch ervation and appreciation of wilderness agree with this statement. Wilderness, Utah. (Right) Historic Varying perspectives derive from a basic diff erence in belief about preservationists complete work on the relationship between humans and the nonhuman world— the Agnes Vaille Shelter historic whether or not humans are a part of nature. For some, wilderness structure at the Keyhole on Longs means pristine nature and the absence of human modifi cation, Peak, Rocky Mountain National where the presence of ancient dwellings, historic sites, or other Park Wilderness, Colorado. NPS/STERLING HOLDORF signs of prior human use degrades wilderness. For others, wilder- ness is a cultural landscape that has been valued, used, and in some areas modifi ed by humans for thousands of years (fi g. 1). Abstract Reconciling these perspectives can be diffi cult. Cultural resources are an integral part of wilderness and wilderness character, and all wilderness areas have a human history. This To foster this reconciliation, the National Park Service (NPS) article develops a foundation for wilderness and cultural resource National Wilderness Steering Committee (now the Wilderness staffs to continue communicating with one another in order to Leadership Council) stated that “National Park Service policies make better decisions for wilderness stewardship. Following a discussion of relevant legislative history, we describe how cultural properly and accurately incorporate cultural resource steward- resources are the fi fth quality of wilderness character. -

Markup Committee on Foreign Affairs House Of

TO DIRECT THE PRESIDENT TO SUBMIT TO CONGRESS A RE- PORT ON FUGITIVES CURRENTLY RESIDING IN OTHER COUN- TRIES WHOSE EXTRADITION IS SOUGHT BY THE UNITED STATES AND RELATED MATTERS; AND TO REQUIRE A RE- GIONAL STRATEGY TO ADDRESS THE THREAT POSED BY BOKO HARAM MARKUP BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 2189 and H.R. 3833 SEPTEMBER 22, 2016 Serial No. 114–227 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 21–607PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 10:37 Nov 08, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_AGH\092216M\21607 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas BRIAN HIGGINS, New York MATT SALMON, Arizona KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E.