An Exploration of the Work of David Bintley, a Very

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© the MORRIS FEDERATION 2015 Morris Federation Committee

Interview: Doug Eunson & Sarah Matthews The Lost Art of Communication The Curious Incident of the Dog, etc. Paul White’s Diary Bells, Broomsticks, One-pots & Tinners Ossett Beer Cart on the Map English Miscellany’s 40 for 40th Bear With Me - It’s All for Charity Cardiff Ladies Morris 1973- 2015 Amazing Headbangers Ridgeway Boards Obituary: Peter Wallis The Geometrical Hedgehog Evesham Weekend © THE MORRIS FEDERATION 2015 Morris Federation Committee President Notation Of cer Melanie Barber Jerry West 72 Freedom Road 23 Avondale Road, Walkley Shef eld Fleet, Hants, S6 2XD GU51 3BH Tel: 0114 232 4840 tel: 01252 628190 [email protected] or 07754 435170 email: [email protected] Secretary Fee Lock Newsletter Editor 28 Fairstone Close Colin Andrews HASTINGS Bonny Green, TN35 5EZ Morchard Bishop, 01424-436052 Crediton, [email protected] EX17 6PG 01363 877216 [email protected] Treasurer Jenny Everett Co-opted members: Willow Cottage 20 High Street Web Site Editor Sutton on Trent Kevin Taylor Newark Notts [email protected] NG23 6QA www.morrisfed.org.uk Tel 01636 821672 [email protected] John Bacon – Licensing Bill Archive Of cer [email protected] Mike Everett Willow Cottage To contact all email-able Federation members: 20 High Street [email protected] Sutton on Trent To notify us of a change of contact details: Newark Notts [email protected] NG23 6QA Tel 01636 821672 For information & advice on Health & Safety: [email protected] [email protected] 0118 946 3125 NEWSLETTER COPY DATES 15th November 15th February 2016 15th May 2016 15th August 2016 Contributions for the Winter edition to the Newsletter Editor by Sunday 15th November [email protected] www.morrisfed.org.uk CONTENTS EDITORIAL Autumn 2015 Marvellous things mobile phones, even though mine’s a pretty basic Nokia with a camera, and, as I discovered in time for the interview in this edition, a Committee Contacts 2 voice recorder as well. -

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

A Mixed Blessing at the Ballet 01

Daily Telegraph July 28 2001 A mixed blessing at the ballet Photo Sheila Rock As Anthony Dowell leaves the Royal Ballet, dance critic Ismene Brown assesses his 15-year regime as director - and stars pay tribute below AT THE Royal Ballet the countdown has begun to the end of an era. A week tonight, amid flowers, Champagne and tears, Sir Anthony Dowell, the longest-serving ballet director since the company’s founder, Ninette de Valois, will end his 15-year regime. He was undoubtedly one of the great world stars of dancing, and the “Celebration Programme” will mark his achievements as such. But about his success as director of the company, opinion is far from unanimous. What makes a good director? The question has never been more of a poser than during Dowell\s captaincy of the ballet, in the most turbulent years of the Royal Opera House’s history. There are many pluses on Dowell’s account sheet - his maintenance of high classical technical standards, his welcoming of key foreign artists into the Royal (particularly Sylvie Guillem and Irek Mukhamedov), his inspiring coaching, to which leading guest stars attest opposite. The rise of Darcey Bussell to world acclaim, the forging of a superb partnership between Mukhamedov and Viviana Durante, this final, nostalgic and beautiful 2000-01 season - these are positive memories. He will be noted as a conservative, and many welcomed this after an insecure period of modernising under his predecessor, Norman Morrice. Whether conservatism has served the company well for the future, though, is debatable. In the shifting landscape of ballet, conservatism is not enough to hold steady. -

British Ballet Charity Gala

BRITISH BALLET CHARITY GALA HELD AT ROYAL ALBERT HALL on Thursday Evening, June 3rd, 2021 with the ROYAL BALLET SINFONIA The Orchestra of Birmingham Royal Ballet Principal Conductor: Mr. Paul Murphy, Leader: Mr. Robert Gibbs hosted by DAME DARCEY BUSSELL and MR. ORE ODUBA SCOTTISH BALLET NEW ADVENTURES DEXTERA SPITFIRE Choreography: Sophie Laplane Choreography: Matthew Bourne Music: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Gran Partita and Eine kleine Nachtmusik Music: Excerpts from Don Quixote and La Bayadère by Léon Minkus; Dancers: Javier Andreu, Thomas Edwards, Grace Horler, Evan Loudon, Sophie and The Seasons, Op. 67 by Alexander Glazunov Martin, Rimbaud Patron, Claire Souet, Kayla-Maree Tarantolo, Aarón Venegas, Dancers: Harrison Dowzell, Paris Fitzpatrick, Glenn Graham, Andrew Anna Williams Monaghan, Dominic North, Danny Reubens Community Dance Company (CDC): Scottish Ballet Youth Exchange – CDC: Dance United Yorkshire – Artistic Director: Helen Linsell Director of Engagement: Catherine Cassidy ENGLISH NATIONAL BALLET BALLET BLACK SENSELESS KINDNESS Choreography: Yuri Possokhov THEN OR NOW Music: Piano Trio No. 1, Op. 8 by Dmitri Shostakovich, by kind permission Choreography: Will Tuckett of Boosey and Hawkes. Recorded by musicians from English National Music: Daniel Pioro and Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber – Passacaglia for solo Ballet Philharmonic, conducted by Gavin Sutherland. violin, featuring the voices of Natasha Gordon, Hafsah Bashir and Michael Dancers: Emma Hawes, Francesco Gabriele Frola, Alison McWhinney, Schae!er, and the poetry of -

David Justin CV 2014 Pennsylvania Ballet

David Justin 4603 Charles Ave Austin TX 787846 Tel: 512-576-2609 Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.davidjustin.net CURRICULUM VITAE ACADEMIC EDUCATION • University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, Master of Arts in Dance in Education and the Community, May 2000. Thesis: Exploring the collaboration of imagination, creativity, technique and people across art forms, Advisor: Tansin Benn • Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, Edward Kemp, Artistic Director, London, United Kingdom, 2003. Certificate, 285 hours training, ‘Acting Shakespeare.’ • International Dance Course for Professional Choreographers and Composers, Robert Cohen, Director, Bretton College, United Kingdom, 1996, full scholarship DANCE EDUCATION • School of American Ballet, 1987, full scholarship • San Francisco Ballet School, 1986, full scholarship • Ballet West Summer Program, 1985, full scholarship • Dallas Metropolitan Ballet School, 1975 – 1985, full scholarship PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Choreographer, 1991 to present See full list of choreographic works beginning on page 6. Artistic Director, American Repertory Ensemble, Founder and Artistic Director, 2005 to present $125,000 annual budget, 21 contract employees, 9 board members11 principal dancers from the major companies in the US, 7 chamber musicians, 16 performances a year. McCullough Theater, Austin, TX; Florence Gould Hall, New York, NY; Demarco Roxy Art House, Edinburgh, Scotland; Montenegrin National Theatre, Podgorica, Montenegro; Miller Outdoor Theatre, Houston, TX, Long Center for the Performing Arts, -

September 4, 2014 Kansas City Ballet New Artistic Staff and Company

Devon Carney, Artistic Director FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Ellen McDonald 816.444.0052 [email protected] For Tickets: 816.931.2232 or www.kcballet.org Kansas City Ballet Announces New Artistic Staff and Company Members Grace Holmes Appointed New School Director, Kristi Capps Joins KCB as New Ballet Master, and Anthony Krutzkamp is New Manager for KCB II Eleven Additions to Company, Four to KCB II and Creation of New Trainee Program with five members Company Now Stands at 29 Members KANSAS CITY, MO (Sept. 4, 2014) — Kansas City Ballet Artistic Director Devon Carney today announced the appointment of three new members of the artistic staff: Grace Holmes as the new Director of Kansas City Ballet School, Kristi Capps as the new Ballet Master and Anthony Krutzkamp as newly created position of Manager of KCB II. Carney also announced eleven new members of the Company, increasing the Company from 28 to 29 members for the 2014-2015 season. He also announced the appointment of four new KCB II dancers, which stands at six members. Carney also announced the creation of a Trainee Program with five students, two selected from Kansas City Ballet School. High resolution photos can be downloaded here. Carney stated, “With the support of the community, we were able to develop and grow the Company as well as expand the scope of our training programs. We are pleased to welcome these exceptional dancers to Kansas City Ballet and Kansas City. I know our audiences will enjoy the talent and diversity that these artists will add to our existing roster of highly professional world class performers that grace our stage throughout the season ahead. -

Chamber Music Concerts Player and Chamber Musician with the Tempest Two Concerts Featuring Rounds for Brass Quintet, Flute Trio

We are Chamber Music We are Opera and Song We are Popular Music Our Chamber Music Festival goes to the city Again in Manchester Cathedral, we will be Following its success at the Royal Albert Hall and Welcome centre (10-12 Jan) using Manchester Cathedral taking the magic and mystery of Orpheus with here at the RNCM last term, the RNCM Session as our hub, and featuring the Academy of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice (28 Mar), which Orchestra returns with an exciting eclectic Ancient Music, the Talich Quartet and The will also be performed alongside his witty programme (25 Apr). Staff-led Vulgar Display Band of Instruments together with our staff The Drunkard Cured (L’ivrogne corrigé) in our give us their take on extreme metal (12 Feb). to the and students, to explore ‘The Art of Bach’. exclusive double-bill in the intimacy of our Our faithful lunchtime concert followers need not worry about the temporary closure of our Studio Theatre (18, 20, 22 and 27 Mar). Opera We are Folk and World Spring Concert Hall. These concerts will be as frequent, Scenes are back (21, 24, 28 and 31 Jan), as Fusing Latin American and traditional Celtic diverse and delightful as ever, in fantastic venues entertaining as ever. Yet another exciting venture folk, Salsa Celtica appear on the RNCM stage such as the Holden Art Gallery, St Ann’s is the one with the Royal Exchange Theatre for (7 Mar), followed by loud, proud acoustic season at Church and the Martin Harris Centre, featuring an extra-indulgent Day of Song (27 Apr) where Bellowhead–founding members, Spiers & the RNCM Chamber Ensemble with Stravinsky’s we will be taking you with us through the lush Boden on their last tour as a duo (20 Mar), The Soldier’s Tale, as well as a feast of other atmosphere of the Secession and travelling from while the award-winning folk band Melrose ensembles: Harp, Saxophone, Percussion and country to country by song throughout the day. -

Diaghilev and London

Diaghilev and London, A Talk by Graham Bennett, Crouch End and District U3A member We are not exactly the best of friends with Russia these days - But just over a century ago, Russia exported something that actually transformed the cultural life of London. This talk is about a quite extraordinary Russian Impresario and two equally extraordinary women who were part of his project The project was a Russian Dance Company that created a revolution in the world of dance, and London was to play a big part in its success. This company is the Ballet Russes. The impresario is Serge Diaghilev, born in 1872 in Perm in deepest Russia, who would create the Ballet Russes. Lydia Lopokova from St Petersburg, born in 1892, one of Diaghilev's star ballerinas. And last but not least, our very own Hilda Munnings from Wanstead in East London, born in 1896. Also to become a vitally important member of the company The story starts in St Petersburg in 1901, the heart of the Russian Empire, at the famous Mariinsky Theatre. Their choreographer Marius Petipa and composer Tchaikovsky had already created masterpieces such as The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker and Swan Lake. These are such familiar names to us today but they were virtually unknown outside Russia at that time. Over in England we were still having a jolly knees up and sing-along at the Music Hall and even in France, ballet had degenerated to a pale shadow of its former glory. In 1901, Lydia Lopokova, just 9 years old, auditioned for a place at the prestigious Imperial Theatre School in St Petersburg. -

WRAP Thesis Ruben 1998.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/59558 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. 1 GRACE UNDER PRESSURE: RE-READING GISELLE. Mel Ruben Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature University of Warwick Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies September, 1998 2 For Peter, Alice, Audrey and Theda Ruben 3 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 6 Summary 7 Terminology 8 Preface 1. Introduction 9 2. My Personal Aims for this Thesis 11 3. My Own Mythology 16 4. Ballet Writing and Ballet Going in the 1990s 20 5. The Shape of Love 35 Notes to the Preface 38 ChaQter One: The Ballet Called Giselle 1. Jntroductton 42 2. Giselle: a Romantic Ballet 42 3. The Plot of Giselle 51 4~The First Giselle 60 5. Twentieth Century Giselles 64 6. The Birmingham Royal Ballet's 1992 Giselle 74 7. Locating Ballet in Dance Studies 86 8. Using Ballet as a Text 91 9. Methodology 98 Notes to Chapter One 107 ChaQter Two Plot: Blade Runner and Giselle 1. Introduction 111 2. The Two Blade Runners 113 3. The Plot of Blade Runner 117 4. Matching the Myths 129 5. Endings and Closures 159 6. -

English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions About Black People in England

Trish Bater 080207052 ‘Blacking Up’: English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions about Black People in England Submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Patricia Bater National Centre for English Cultural Tradition March 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Trish Bater 080207052 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the custom of white people blacking their faces and its continuation at a time when society is increasingly aware of accusations of racism. To provide a context, an overview of the long history of black people in England is offered, and issues about black stereotypes, including how ‘blackness’ has been perceived and represented, are considered. The historical use of blackface in England in various situations, including entertainment, social disorder, and tradition, is described in some detail. It is found that nowadays the practice has largely been rejected, but continues in folk activities, notably in some dance styles and in the performance of traditional (folk) drama. Research conducted through participant observation, interview, case study, and examination of web-based resources, drawing on my long familiarity with the folk world, found that participants overwhelmingly believe that blackface is a part of the tradition they are following and is connected to its past use as a disguise. However, although all are aware of the sensitivity of the subject, some performers are fiercely defensive of blackface, while others now question its application and amend their ‘disguise’ in different ways. -

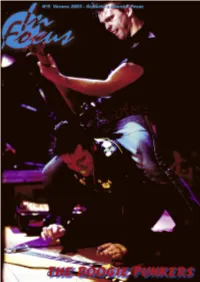

In Focus 5. Verano 2003. the Boogie Punkers. (PDF

Editorial Sumario LA CRÍTICA, EL CRÍTICO, EL CRITERIO REPORTAJES (004) Curiosos palabros estos tres. Al crítico no le (002) The Boogie Punkers gusta formar parte de la crítica pero se sabe (006) Los Del Tonos poseedor de criterio. El criticado cuando recibe (009) Doctor Deseo una buena crítica piensa que está hecha con cri- (015) Fito y Fitipaldis (016) Edu "Bighands" terio, así que si tiene ocasión se lo hace saber al (018) Gorka Gassman crítico, y el crítico, claro está, opina entonces que (020) Los Padrinos el criticado tiene criterio al criticar su crítica. (023) Sanchís y Jocano Suena críptico pero suele ser así. (027) Séan Keane (029) Tres Hombres Bien, ¿qué facultades debe tener un crítico? En (031) E- Bow el caso que nos ocupa, se supone que cultura (034) Bad- F Line musical. No problemo, si hay que escuchar dis- (036) The Cumshots cos, se escuchan, mola. Pero el problema está en (038) Dover las condiciones. Si eres de una discográfica y (040) El Drogas y el Kutxi quieres venderme a tu grupo, hazme el favor (043) Koniec (045) Mike Sobieski (ironía) de mandarme un disco, y no un Cd-R sin (046) Motorhead títulos, sin créditos, sin contactos y sin nada ("tie- (049) Obligaciones nes fotos en la güéf"). Si tu grupo está presen- (051) Los Reyes del KO tando su última grabación, no me entregues la (054) Peer Wyboris víspera de la rueda de prensa el disco ("por men- (058) Sharon Sahnnon (060) Shisha Pangma sajero, que corre prisa") y me sueltes encima la BREVES (062) puntilla: "les preguntas cuatro bobadas". -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} History and the Morris Dance: a Look

HISTORY AND THE MORRIS DANCE: A LOOK AT MORRIS DANCING FROM ITS EARLIEST DAYS UNTIL 1850 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dr. John Cutting | 204 pages | 31 Jan 2010 | Dance Books Ltd | 9781852731083 | English | Hampshire, United Kingdom Modern dance | Britannica Cunningham, who would have turned this year, would sometimes flip a coin to decide the next move, giving his work a nonlinear, collagelike quality. These were ideas simultaneously being explored in visual art, which was engaged in a similar resetting of boundaries as Pop, Minimalism and conceptual art replaced Abstract Expressionism, with which modern dance was closely aligned; for one, both were preoccupied with working on the floor, as in the paintings of Jackson Pollock and the dances of Martha Graham. Postmodernists remained keen on gravity, however. Certain choreographers would come to treat the floor as a dance partner, just as multidisciplinary artists like Ana Mendieta and Bruce Nauman used it in their performance pieces as a site for symbolic regeneration or heady writhing. Forti considered her work as much dance as sculpture, its human performers art objects like any other — but it hardly mattered, since, for this brief and exceptional window, art, dance and music were almost synonymous. The s New York art scene was famously small, and disciplines blended together as a result. In time, though, the moment of equilibrium passed and the community collapsed, reality itself acting as a sort of score. After the last Judson dance concert in , Childs taught elementary school for five years to support herself before returning to the field. Forti lived for a time in Rome, crossing paths with the Arte Povera movement, and Deborah Hay eventually landed in Austin, where she hosted group workshops.