The Policing Question. Protection Vs. Service in 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

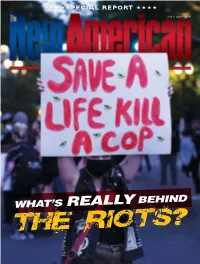

What's Really Behind

SPECIAL REPORT July 6, 2020 • $3.95 WHAT’S REALLY BEHIND featured KEEPING HIS CREATIONS THRIVING FOR YOU FOR YOUR PET Our Mission: To serve the Lord and glorify Him using the gifts He has given our employees to research, develop, manufacture, and market products that improve the quality of life for people and their pets. Human products on Nutramaxlabs.com are sold by Nutramax Laboratories Consumer Care, Inc. Veterinary products on Nutramaxlabs.com are sold by Nutramax Laboratories Veterinary Sciences, Inc. 410.1024.00 nutramaxlabs.com Who Are Your Local Police? — PAMPHLET Use this pamphlet to inform local police, opin- ion molders, and voters in general. The pam- phlet summarizes the proper role of the local police in our constitutional republic and the need for local police departments to remain Local vs. National Police & What’s independent by rejecting federal funds. It also Happening to Our Police? warns against nationalizing our police. (2014, Use this dual-feature DVD to learn the differ- four-color trifold pamphlet, 1-99/$0.20; ence between local and national police, as well 100-499/$0.15ea; 500-999/$0.13ea; as the agenda behind the attacks on local police. 1,000+/$0.10ea) PSYLP (2015, 4min + 10min, 1-10/$1.00; 11-20/$0.90ea; 21-49/$0.80ea; 50-99/$0.75ea; 100-999/$0.70ea; 1,000+/$0.64ea) DVDDLVNWHP SYLP “What Can I Do”? Policing Police — SLIM JIM — REPRINT Hand out these slim jims Anti-police sentiments have at your next event to get been steadily gathering steam, your local community gaining new followers, and members involved in the leading to calls for Civilian SYLP campaign. -

If You're Having Trouble Loading It, a Smaller Version Is Here

1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Staff Report- Senior Pastor Anne J. Scalfaro__________________________________________________3 A Few of Anne’s Notable Pastor Letters in the E-News This Year______________________________8 Annual Enrollment Report _______________________________________________________________19 Staff Report - Dr. David Farwig___________________________________________________________21 Staff Report- Rev. Alice Horner Nelson____________________________________________________22 2020 Website Statistics__________________________________________________________________23 2020 YouTube Statistics________________________________________________________________ 24 Report from Staff Relations______________________________________________________________24 Building Updates________________________________________________________________________25 Report from Stewardship Committee______________________________________________________27 Report from the Co-Moderators of Council________________________________________________29 Staff Report- Rev. Morgan C. Fletcher____________________________________________________31 Faith Formation - Church School Classes__________________________________________________33 Caritas Explorers Ribbons Voyagers Koinonia Little Free Library Report_______________________________________________________________ 34 Staff Report- Angela Leonard____________________________________________________________35 Staff Report - Rev. Mary Hulst ___________________________________________________________37 Foot of the Cross Courtyard -

Anti-Racism Resources

Anti-Racism Resources Prepared for and by: The First Church in Oberlin United Church of Christ Part I: Statements Why Black Lives Matter: Statement of the United Church of Christ Our faith's teachings tell us that each person is created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27) and therefore has intrinsic worth and value. So why when Jesus proclaimed good news to the poor, release to the jailed, sight to the blind, and freedom to the oppressed (Luke 4:16-19) did he not mention the rich, the prison-owners, the sighted and the oppressors? What conclusion are we to draw from this? Doesn't Jesus care about all lives? Black lives matter. This is an obvious truth in light of God's love for all God's children. But this has not been the experience for many in the U.S. In recent years, young black males were 21 times more likely to be shot dead by police than their white counterparts. Black women in crisis are often met with deadly force. Transgender people of color face greatly elevated negative outcomes in every area of life. When Black lives are systemically devalued by society, our outrage justifiably insists that attention be focused on Black lives. When a church claims boldly "Black Lives Matter" at this moment, it chooses to show up intentionally against all given societal values of supremacy and superiority or common-sense complacency. By insisting on the intrinsic worth of all human beings, Jesus models for us how God loves justly, and how his disciples can love publicly in a world of inequality. -

1. Petitions to Sign 2. Protestor Bail Funds 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations 4

Disclaimer and Credit: This is by no means comprehensive, but rather a list we hope you find helpful as a starting point to begin or to continue to support our Black brothers, sisters, communities and patients. Thank you to the Student National Medical Association chapter at George Washington University School of Medicine for compiling many of these resources. Editing Guidelines: Please feel free to add any resources that you feel are useful. Any inappropriate edits will be deleted and editing capabilities will be revoked. Table of Contents 1. Petitions To Sign 2. Protestor Bail Funds 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations 4. Mental Health Resources 5. Anti-Racism Reading and Resource List 6. Media 7. Voter Registration and Related Information 8. How to Support Memphis 1. Petitions To Sign *Please note that should you decide to sign a petition on change.org, DO NOT donate through change.org. Rather, donate through the websites specific to the organizations to ensure your donated funds are going directly to the organization. ● Justice for George Floyd ● Justice for Breonna ● Justice for Ahmaud Arbery ● We Can’t Breathe ● Justice for George Floyd 2. Protestor Bail Funds ● National Bail Fund Network (by state) ○ This link includes links to various cities ● Restoring Justice (Legal & Social services) 3. Organizations That Need Our Support and Donations Actions are loud. As students, we know that money is tight. But if each of us donated just $5 to one cause, together we could demand a great impact. ● Black Visions Collective (Minnesota Based): “BLVC is committed to a long term vision in which ALL Black lives not only matter, but are able to thrive. -

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020

Resources on Racial Justice June 8, 2020 1 7 Anti-Racist Books Recommended by Educators and Activists from the New York Magazine https://nymag.com/strategist/article/anti-racist-reading- list.html?utm_source=insta&utm_medium=s1&utm_campaign=strategist By The Editors of NY Magazine With protests across the country calling for systemic change and justice for the killings of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, many people are asking themselves what they can do to help. Joining protests and making donations to organizations like Know Your Rights Camp, the ACLU, or the National Bail Fund Network are good steps, but many anti-racist educators and activists say that to truly be anti-racist, we have to commit ourselves to the ongoing fight against racism — in the world and in us. To help you get started, we’ve compiled the following list of books suggested by anti-racist organizations, educators, and black- owned bookstores (which we recommend visiting online to purchase these books). They cover the history of racism in America, identifying white privilege, and looking at the intersection of racism and misogyny. We’ve also collected a list of recommended books to help parents raise anti-racist children here. Hard Conversations: Intro to Racism - Patti Digh's Strong Offer This is a month-long online seminar program hosted by authors, speakers, and social justice activists Patti Digh and Victor Lee Lewis, who was featured in the documentary film, The Color of Fear, with help from a community of people who want and are willing to help us understand the reality of racism by telling their stories and sharing their resources. -

Dear Stanford Zumba Community, Ordinarily, Our Friday Email Would Confirm This Week's Remote Class and Celebrate the Weekend

Dear Stanford Zumba Community, Ordinarily, our Friday email would confirm this week’s remote class and celebrate the weekend with dance and energy. But this has been a week of immense pain, sadness, and anger. It is time not to celebrate, but to speak up and stand firm. Stanford Zumba stands in solidarity with Black Lives Matter and the Black community. We share in the pain caused by the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, Admaud Arbery, Eric Garner, Philando Castile, Trayvon Martin and countless other Black folks, and vow to be part of the movement toward real change. For these reasons, we will not have classes this week. Our Core team recognizes that systemic racism is a deep-seated plague, with police brutality as one manifestation. We have been reflecting on ways that we occupy systems founded on white supremacy, tracing back to the origins of this country. For non-Black folks, to not actively fight for racial justice is to accept those oppressive systems. With this in mind, we pledge to have a fundraiser for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in the future; we will share more details in the coming weeks. We have also been reflecting on the ways that we have benefited from the many contributions of Black folks. As Zumba instructors, our choreographies and music are often created by or draw inspiration from Black artists. We pledge to celebrate their voices in a way that upholds dignity and respect. We also recognize that both the Civil Rights and Pride movements were major landmarks of progress led by Black activists. -

In Solidarity — a Note from Shelly

June 4, 2020: In Solidarity — A Note from Shelly Dear CDS Family, As a white person, no matter how closely I am an observer, I will NEVER understand the suffering in our Black community. What we are witnessing now is the manifestation of years of pain, trauma, and the pushing down of emotions in response to systemic state-sanctioned racial violence and police brutality. At this moment, the pain is present and acute. The critical way forward is to keep the observance of this pain in mind as we navigate the next steps individually and collectively. For some additional learning and perspective, watch the film Just Mercy (streaming for free this month) and Bryan Stevenson’s follow-up TED talk. As a faculty and staff community, we have committed to putting our resources where they can help. Together, we have donated more than $4,100 to the organizations listed at the bottom of this email. Some have made monthly commitments and others are first-time connections to organizations which may become a lifelong philanthropic focus. We encourage you and your family to donate what you can to organizations defending and celebrating Black lives as well as individuals in your community who are in need. Another opportunity to stand up is to support Black-owned restaurants in the Bay Area with your business. I thought this article would resonate with you as you support your children and yourself in unpacking this complex topic of race. Woke Kindergarten’s Word of the Day - Protest offers young children an age-appropriate perspective on the protests and can be a catalyst to start or continue your conversations at home. -

A Statement Regarding the Wellbeing of Black Students and Cases of Police Violence in the United States May 29, 2020

Student Government Assembly 60 Washington Square South, Suite 212 NY, NY 10003 P: 212 998 2234 [email protected] A Statement Regarding the Wellbeing of Black Students and Cases of Police Violence in the United States May 29, 2020 Dear NYU Community: The Student Government Assembly Executive Committee and Senators at-Large for Black Students wish to acknowledge the injustices and crimes against humanity that have recently been committed by members of the Minneapolis Police Department, resulting in protests across the nation. Times like these call for moments of both personal and communal reflection into the institutionalized racism that plagues our community, and reiterates the importance of using our voices to make change. The horrific murder of George Floyd on May 25th, along with the murder of countless other innocent African Americans, requires us, as students, to be loud and bold. These moments ask us to look beyond ourselves, our privilege, and our own silence. In doing so, we are able to support our fellow Black sisters and brothers when they need us most. In recent years, we have become familiar with the ways in which silence can be just as deadly as the racism and police brutality that took Mr. Floyd’s life. For that reason, the Student Government Assembly has made the elevation and projection of Black voices its primary goal in this time of great loss. While the Student Government Assembly does not encourage violence, it supports in solidarity the large-scale protests in cities across the United States. It is our belief that such protests, including recent violence, are the result of years of failure on behalf of the state to protect the bodies of Black people in the face of racist policing and widespread discrimination. -

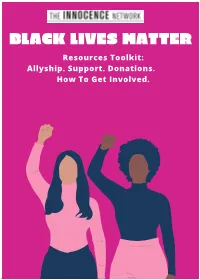

View the Innocence Network Resource Guide

BLACK LIVES MATTER Resources Toolkit: Allyship. Support. Donations. How To Get Involved. Donate Here: GEORGE FLOYD MEMORIAL FUND I RUN WITH MAUD MEMORIAL FUND FOR AHMEAD ARBERY Pay Bail and Bond for Arrested Activists Minnesota Freedom Fund Louisville Community Bail Fund The Bail Project (National) National Bailout Fund (National) List of Bail Funds By State Sign the Petition Here https://justiceforbreonna.org DONATE HERE Registering Black Voters and Fighting Voter Suppression Black Votes Matter Fund Fair Fight Developing Data Driven Policy Solutions on Police Brutality Mapping Police Violence Other Organizations Color of Change NAACP Legal Defense Fund Movement For Black Lives Communites United Against Police Brutality Gas Mask Fund Black Visions Collective P R O T E S T 1.Find a Black Lives Matter Chapter 2.Ensure you're protesting saftely 10 Steps to Non-Optical Allyship @MIREILLECHARPER 1.Understanding what optical allyship is "allyship that only serves at the surface level to platform the 'ally,' it makes a statement but doesn't go beneath the surface and is not aimed at breaking away from the sysytems of power that oppress." - Latham Thomas 10 Steps to Non-Optical Allyship @MIREILLECHARPER 2. Check in on your black friends, family, partners, loved ones and colleagues The is an emotional and traumatic time for the community, and you checking in means more than you can imagine. Ask how you can provide support. But please keep in mind power dynamics and privilege in the workplace among colleagues. Some folks might not feel comfrotable sharing and that is okay. Ask yourself are you reaching out for them or for YOU. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Winona Laduke

MINNESOTA WOMEN’S PRESS The Climate ’s Press en 20 om 20 W a t o s e n n i M s r e n in w Lo ur ok o inside for the Climate Issue | womenspress.com | July 2020 | Issue 36-7 MINNESOTA The law of evolution is that the strongest survives. Yes, and the WOMEN’S PRESSPOWERFUL. EVERYDAY. WOMEN. strongest, in the existence of any social species, are those who are most social. In human terms, most ethical. There is no strength to be gained from hurting one another. Only weakness. — Ursula K. LeGuin PHOTO SARAH WHITING SARAH PHOTO What’s inside? Editor Letter 3 On the Nature of Being a Doula Tapestry 4-5 An Evolution in Our Ecosystem Politics & Policy 6-7 Kristel Porter: Lobbying for Justice Gaea Dill-D’Ascoli, Page 12 Eco-lution 8-9 Winona LaDuke: Leader of Green Revolution Contact Us MWP team Perspectives 10-11 Climate Generation: Youth Take Action 651-646-3968 Publisher/Editor: Mikki Morrissette Submit a story: [email protected] Money & Business 12-13 Managing Editor: Sarah Whiting Gaea Dill-D’Ascoli: My Movement to Solar Subscribe: [email protected] Business Strategy Director: Shelle Eddy Ecosystem 14-15 Advertise: [email protected] Contributors: Christine Baeumler, Climate How Minnesota Women Are Restoring Earth Our mission: Amplify and inspire, with personal Generation writers, Meredith Cornett, Gaea Dill- D’Ascoli, Kristel Porter BookShelf 16-17 stories and action steps, the voice, vision, and Meredith Cornett: Climate Consciousness leadership of powerful, everyday women. Community Engagement: Siena Iwasaki Milbauer, Lydia Moran, Ryan Stevens, Kassidy Tarala GoSeeDo 21 Our vision: We all are parts of a greater whole. -

N E W S L E T T

Harvard University Department of M usic MUSICnewsletter Vol. 21, No. 1 Winter 2021 Community Building and Social Justice Through Music Harvard University “This is my favorite way to Department of Music teach—and learn,” says Professor 3 Oxford Street of the Practice Claire Chase of her Cambridge, MA 02138 Freshman Seminar, Community Building and Social Justice through 617-495-2791 Music. “In my own music education, music.fas.harvard.edu the transformative moments for me always took place when an elder invited me to do work alongside them—not just for them—and when INSIDE they invited me into their practice, assuming that I would rise to the 3 Faculty News occasion. I wanted to invite these 4 Ask the Experts: How Ford, freshmen into the process of making Rockefeller, and the NEA work alongside some of the greatest artists of our time. They have more Changed American Music than risen to the occasion.” 5 BLM: an open letter from the Chase commissioned the Hous- Department of Music ton composer, percussionist, and 6 Alumni News sound artist Susie Ibarra to create an interactive, virtual musical score with 8 Spring Events: Laurie Anderson, the fifteen students in her seminar. Miranda Cuckson, Parker “Susie has done a number of 9 Library News virtual soundwalk projects—in the 10 Graduate Student News Philippines, New York and Pitts- burgh, to name a few—but never 11 Undergraduate Student News with students on a college campus. She completely embraced the notion that many of these students would be composing music for the first time.” The result: Digital Sanctuar- ies Harvard, a soundwalk app that We have a new YouTube chan- invites the public to take a virtual nel.