156. FOURTH MOVEMENT Classical Music and Total War: a New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES Composers

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KHAIRULLO ABDULAYEV (b. 1930, TAJIKISTAN) Born in Kulyab, Tajikistan. He studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory under Anatol Alexandrov. He has composed orchestral, choral, vocal and instrumental works. Sinfonietta in E minor (1964) Veronica Dudarova/Moscow State Symphony Orchestra ( + Poem to Lenin and Khamdamov: Day on a Collective Farm) MELODIYA S10-16331-2 (LP) (1981) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where he studied under Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. His other Symphonies are Nos. 1 (1962), 3 in B flat minor (1967) and 4 (1969). Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1964) Valentin Katayev/Byelorussian State Symphony Orchestra ( + Vagner: Suite for Symphony Orchestra) MELODIYA D 024909-10 (LP) (1969) VASIF ADIGEZALOV (1935-2006, AZERBAIJAN) Born in Baku, Azerbaijan. He studied under Kara Karayev at the Azerbaijan Conservatory and then joined the staff of that school. His compositional catalgue covers the entire range of genres from opera to film music and works for folk instruments. Among his orchestral works are 4 Symphonies of which the unrecorded ones are Nos. 1 (1958) and 4 "Segah" (1998). Symphony No. 2 (1968) Boris Khaikin/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1968) ( + Piano Concertos Nos. 2 and 3, Poem Exaltation for 2 Pianos and Orchestra, Africa Amidst MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Symphonies A-G Struggles, Garabagh Shikastasi Oratorio and Land of Fire Oratorio) AZERBAIJAN INTERNATIONAL (3 CDs) (2007) Symphony No. -

A Russian Eschatology: Theological Reflections on the Music of Dmitri Shostakovich

A Russian Eschatology: Theological Reflections on the Music of Dmitri Shostakovich Submitted by Anna Megan Davis to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology in December 2011 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. 2 3 Abstract Theological reflection on music commonly adopts a metaphysical approach, according to which the proportions of musical harmony are interpreted as ontologies of divine order, mirrored in the created world. Attempts to engage theologically with music’s expressivity have been largely rejected on the grounds of a distrust of sensuality, accusations that they endorse a ‘religion of aestheticism’ and concern that they prioritise human emotion at the expense of the divine. This thesis, however, argues that understanding music as expressive is both essential to a proper appreciation of the art form and of value to the theological task, and aims to defend and substantiate this claim in relation to the music of twentieth-century Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich. Analysing a selection of his works with reference to culture, iconography, interiority and comedy, it seeks both to address the theological criticisms of musical expressivism and to carve out a positive theological engagement with the subject, arguing that the distinctive contribution of Shostakovich’s music to theological endeavour lies in relation to a theology of hope, articulated through the possibilities of the creative act. -

Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin's Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowsk

Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin’s Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowski BMUS, University of Victoria, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Music Monika Zaborowski, 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin’s Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowski BMUS, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Susan Lewis-Hammond, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Bruce Vogt, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Michelle Fillion, (School of Music) Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Susan Lewis-Hammond, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Bruce Vogt, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Michelle Fillion, (School of Music) Departmental Member One of the major problems faced by performers of Chopin’s mazurkas is recapturing the elements that Chopin drew from Polish folk music. Although scholars from around 1900 exaggerated Chopin’s quotation of Polish folk tunes in their mixed agendas that related ‘Polishness’ to Chopin, many of the rudimentary and more complex elements of Polish folk music are present in his compositions. These elements affect such issues as rhythm and meter, tempo and tempo fluctuation, repetitive motives, undulating melodies, function of I and V harmonies. During his vacations in Szafarnia in the Kujawy region of Central Poland in his late teens, Chopin absorbed aspects of Kujaw performing traditions which served as impulses for his compositions. -

The Conductor Production Pack

The Conductor Production Pack Tratto dal romanzo di Sarah Quigley Adattamento di Mark Wallington con Jared McNeill 2 attori, 1 pianista Musica de: Sinfonia n.7 in C maggiore, op. 60 Composta da Dmitri Shostakovich Arrangiata e Suonata da Daniel Wallington Con Joe Skelton, Deborah Wastell Diretto da Jared McNeill English Language Running time: 70 minutes Best-suited for Adults/Young Adults Contact: [email protected] 1.....Note del Regista 2.....Sinossi 3.....Foto di Scena 4.....Tourne e Festival 5.....Biografie degli Artisti 6.....Link Video 7.....Recensioni NOTE DEL REGISTA Quando ho iniziato questo lavoro, non avevo molta, o forse alcuna, preparazione sulle opere di Shostakovich, e nemmeno sull' assedio a sfondo sovietico durante il quale "La sinfonia di Leningrado" fu composta. La mia finestra non si apre sull' apprezzamento per la musica "colta", per le parole "colte", o per il teatro "colto". Rimango incerto sul come quantificare i meriti di questa creazione, sia artisticamente che altro. Di certo posso dire che negli ultimi giorni, e negli ultimi anni, mentre guardo quello che succede nella mia terra natale, e in tutto il mondo che incontro e di cui divento consapevole, nelle tourné con Peter Brook e MarieHelene Estienne, sono sempre colpito dalle conversazioni universali sull'identità, il diritto alla vita, la soggettivita' della giustizia, l'emarginazione dell' "altro", e dalla resistenza della natura dell'amore, dell' odio, e della fede . Mi preoccupo a volte di non saper chiarire che questo spettacolo non e' indirizzato solo ad amanti della musica classica, o a storici appassionati. E' stato creato, proprio come la stessa " Sinfonia", per tutti; e pur riferendosi ad eventi del passato, questa storia trova la sua origine e la sua ragione nel nostro mondo presente, e ad esso si rivolge. -

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One

ANATOLY ALEXANDROV Piano Music, Volume One 1 Ballade, Op. 49 (1939, rev. 1958)* 9:40 Romantic Episodes, Op. 88 (1962) 19:39 15 No. 1 Moderato 1:38 Four Narratives, Op. 48 (1939)* 11:25 16 No. 2 Allegro molto 1:15 2 No. 1 Andante 3:12 17 No. 3 Sostenuto, severo 3:35 3 No. 2 ‘What the sea spoke about 18 No. 4 Andantino, molto grazioso during the storm’: e rubato 0:57 Allegro impetuoso 2:00 19 No. 5 Allegro 0:49 4 No. 3 ‘What the sea spoke of on the 20 No. 6 Adagio, cantabile 3:19 morning after the storm’: 21 No. 7 Andante 1:48 Andantino, un poco con moto 3:48 22 No. 8 Allegro giocoso 2:47 5 No. 4 ‘In memory of A. M. Dianov’: 23 No. 9 Sostenuto, lugubre 1:35 Andante, molto cantabile 2:25 24 No. 10 Tempestoso e maestoso 1:56 Piano Sonata No. 8 in B flat, Op. 50 TT 71:01 (1939–44)** 15:00 6 I Allegretto giocoso 4:21 Kyung-Ah Noh, piano 7 II Andante cantabile e pensieroso 3:24 8 III Energico. Con moto assai 7:15 *FIRST RECORDING; **FIRST RECORDING ON CD Echoes of the Theatre, Op. 60 (mid-1940s)* 14:59 9 No. 1 Aria: Adagio molto cantabile 2:27 10 No. 2 Galliarde and Pavana: Vivo 3:20 11 No. 3 Chorale and Polka: Andante 2:57 12 No. 4 Waltz: Tempo di valse tranquillo 1:32 13 No. 5 Dances in the Square and Siciliana: Quasi improvisata – Allegretto 2:24 14 No. -

The Performing Style of Alexander Scriabin

Performance Practice Review Volume 18 | Number 1 Article 4 "The eP rforming Style of Alexander Scriabin" by Anatole Leikin Lincoln M. Ballard Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Ballard, Lincoln M. (2013) ""The eP rforming Style of Alexander Scriabin" by Anatole Leikin," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 18: No. 1, Article 4. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201318.01.04 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol18/iss1/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book review: Leikin, Anatole. The Performing Style of Alexander Scriabin. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011. ISBN 978-0-7546-6021-7. Lincoln M. Ballard Nearly a century after the death of Russian pianist-composer Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915), his music remains as enigmatic as it was during his lifetime. His output is dominated by solo piano music that surpasses most amateurs’ capabilities, yet even among concert artists his works languish on the fringes of the standard repertory. Since the 1980s, Scriabin has enjoyed renewed attention from scholars who have contributed two types of studies aside from examinations of his cultural context: theoretical analyses and performance guides. The former group considers Scriabin as an innovative harmoni- cist who paralleled the Second Viennese School’s development of post-tonal procedures, while the latter elucidates the interpretive and technical demands required to deliver compelling performances of his music. -

Mozart Complete Fortepiano Concertos Author: Jed Distler

A1 Mozart Complete Fortepiano Concertos Author: Jed Distler Recorded in 2004-06, this Mozart piano concerto cycle first appeared on the small Pro Musica Camerata laBel. In the main, fortepianist Viviana Sofronitsky (stepdaughter of the legendary Russian pianist Vladimir), conductor Tadeusz Karolak and the Musica Antiqua Collegium Varsoviense offer less consistent satisfaction in comparison with complete period instrument sets from Bilson/ Gardiner/English Baroque Soloists (DG) and Immerseel/Anima Eterna Orchestra (Channel Classics). The strings prove alarmingly uneven: scrawny-toned in K503ʼs Rondo, hideously ill-tuned in K595ʼs first movement, yet firmly focused in the sparsely scored K413, 414 and 415 group and the youthful first four concertos, where Sofronitskyʼs nimBle harpsichord mastery oozes sparkle and wit. However, her fortepiano artistry yields mixed results. Her heavy-handed articulation, pounded out Alberti Basses and crude down-Beat accents roB certain Rondo movements of their prerequisite animation and lilt, such as those in K271, 450, 459, 482 and 595. And when you juxtapose her Brusque, dynamically unvaried treatment of the latterʼs Larghetto with Bilsonʼs graceful lyricism, her faster Basic tempo actually seems slower. Orchestrally speaking, little sense of long line and amorphous melody/ accompaniment textures yield rudderless slow movements in K271 and K456 while, at the same time, the rich contrapuntal writing in the Adagio of K488 could hardly By more viBrant and roBust; the first Bassoonist really shines here and in the Allegro assaiʼs rapid solo licks. Strange how percussively the Busy passagework in the outer movements of the E flat Double Concerto (K365) registers, whereas the more difficult-to-Balance Triple Concerto (K242) Benefits from superior microphone placement. -

Alexander Scriabin (1871-1915): Piano Miniature As Chronicle of His

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN (1871-1915): PIANO MINIATURE AS CHRONICLE OF HIS CREATIVE EVOLUTION; COMPLEXITY OF INTERPRETIVE APPROACH AND ITS IMPLICATIONS Nataliya Sukhina, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2008 APPROVED: Vladimir Viardo, Major Professor Elvia Puccinelli, Minor Professor Pamela Paul, Committee Member Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Sukhina, Nataliya. Alexander Scriabin (1871-1915): Piano miniature as chronicle of his creative evolution; Complexity of interpretive approach and its implications. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2008, 86 pp., 30 musical examples, 3 tables, 1 figure, references, 70 titles. Scriabin’s piano miniatures are ideal for the study of evolution of his style, which underwent an extreme transformation. They present heavily concentrated idioms and structural procedures within concise form, therefore making it more accessible to grasp the quintessence of the composer’s thought. A plethora of studies often reviews isolated genres or periods of Scriabin’s legacy, making it impossible to reveal important general tendencies and inner relationships between his pieces. While expanding the boundaries of tonality, Scriabin completed the expansion and universalization of the piano miniature genre. Starting from his middle years the ‘poem’ characteristics can be found in nearly every piece. The key to this process lies in Scriabin’s compilation of certain symbolical musical gestures. Separation between technical means and poetic intention of Scriabin’s works as well as rejection of his metaphysical thought evolution result in serious interpretive implications. -

Dmitry Shostakovich's <I>Twenty-Four Preludes and Fugues</I> Op. 87

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music Music, School of Spring 4-23-2010 Dmitry Shostakovich's Twenty-Four Preludes and Fugues op. 87: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of the Printed Edition Based on the Composer's Recorded Performance Denis V. Plutalov University of Nebraska at Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Composition Commons Plutalov, Denis V., "Dmitry Shostakovich's Twenty-Four Preludes and Fugues op. 87: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of the Printed Edition Based on the Composer's Recorded Performance" (2010). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH'S TWENTY-FOUR PRELUDES AND FUGUES, OP. 87: AN ANALYSIS AND CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE PRINTED EDITION BASED ON THE COMPOSER'S RECORDED PERFORMANCE by Denis V. Plutalov A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Mark Clinton Lincoln, Nebraska May 2010 Dmitry Shostakovich's Twenty-Four Preludes and Fugues op. 87: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of the Printed Edition Based on the Composer's Recorded Performance Denis Plutalov, D. -

Vladimir PUTIN

7/11/2011 SHANGHAI COOPERATION ORGAniZATION: NEW WORD in GLOBAL POLitics | page. 7 IS THE “GREAT AND POWERFUL uniON” BACK? | page. 21 MIKHAIL THE GREAT | page. 28 GRIEVES AND JOYS OF RussiAN-CHINESE PARtnERSHIP | page. 32 CAspiAN AppLE OF DiscORD | page. 42 SKOLKOVO: THE NEW CitY OF THE Sun | page. 52 Vladimir PUTIN SCO has become a real, recognized factor of economic cooperation, and we need to fully utilize all the benefits and opportunities of coop- eration in post-crisis period CONTENT Project manager KIRILL BARSKY SHANGHAI COOPERAtiON ORGAniZAtiON: Denis Tyurin 7 NEW WORD in GLOBAL POLitics Editor in chief Государственная корпорация «Банк развития и внешнеэконо- Tatiana SINITSYNA 16 мической деятельности (внешэкономБанк)» Deputy Editor in Chief TAtiANA SinitsYNA Maxim CRANS 18 THE summit is OVER. LONG LivE THE summit! Chairman of the Editorial Board ALEXANDER VOLKOV 21 IS THE “GREAT AND POWERFUL uniON” BACK? Kirill BARSKIY ALEXEY MASLOV The Editorial Board 23 SCO UnivERsitY PROJEct: DEFinitELY succEssFUL Alexei VLASOV Sergei LUZyanin AnATOLY KOROLYOV Alexander LUKIN 28 MIKHAIL THE GREAT Editor of English version DmitRY KOSYREV Natalia LATYSHEVA 32 GRIEVES AND JOYS OF RussiAN-CHINESE PARtnERSHIP Chinese version of the editor FARIBORZ SAREMI LTD «International Cultural 35 SCO BECOMES ALTERNAtivE TO WEst in AsiA transmission ALEXANDER KnYAZEV Design, layout 36 MANAGEABLE CHAOS: US GOAL in CEntRAL AsiA Michael ROGACHEV AnnA ALEKSEYEVA Technical support - 38 GREENWOOD: RussiAN CHinESE MEGA PROJEct Michael KOBZARYOV Andrei KOZLOV MARinA CHERNOVA THE citY THEY COULD NEVER HAVE CAptuRED... 40 Project Assistant VALERY TumANOV Anastasia KIRILLOVA 42 CAspiAN AppLE OF DiscORD Yelena GAGARINA Olga KOZLOva 44 SECOND “GOLDEN” DECADE OF RussiAN-CHINESE FRIENDSHIP AnDREI VAsiLYEV USING MATERIALS REFERENCE TO THE NUMBER INFOSCO REQUIRED. -

TOCC0500DIGIBKLT.Pdf

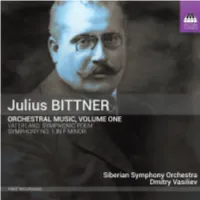

JULIUS BITTNER, FORGOTTEN ROMANTIC by Brendan G. Carroll Julius Bittner is one of music’s forgotten Romantics: his richly melodious works are never performed today and he is perhaps the last major composer of the early twentieth century to have been entirely ignored by the recording industry – until now: apart from four songs, this release marks the very first recording of any of his music in modern times. It reveals yet another colourful and individual voice among the many who came to prominence in the period before the First World War – and yet Bittner, an important and integral part of Viennese musical life before the Nazi Anschluss of 1938 subsumed Austria into the German Reich, was once one of the most frequently performed composers of contemporary opera in Austria. He wrote in a fluent, accessible and resolutely tonal style, with an undeniable melodic gift and a real flair for the stage. Bittner was born in Vienna on 9 April 1874, the same year as Franz Schmidt and Arnold Schoenberg. Both of his parents were musical, and he grew up in a cultured, middle-class home where artists and musicians were always welcomed (Brahms was a friend of the family). His father was a lawyer and later a distinguished judge, and initially young Julius followed his father into the legal profession, graduating with honours and eventually serving as a senior member of the judiciary throughout Lower Austria, until 1920. He subsequently became an important official in the Austrian Department of Justice, until ill health in the mid-1920s forced him to retire (he was diabetic). -

Cello Concerto (1990)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers A-G RUSTAM ABDULLAYEV (b. 1947, UZBEKISTAN) Born in Khorezm. He studied composition at the Tashkent Conservatory with Rumil Vildanov and Boris Zeidman. He later became a professor of composition and orchestration of the State Conservatory of Uzbekistan as well as chairman of the Composers' Union of Uzbekistan. He has composed prolifically in most genres including opera, orchestral, chamber and vocal works. He has completed 4 additional Concertos for Piano (1991, 1993, 1994, 1995) as well as a Violin Concerto (2009). Piano Concerto No. 1 (1972) Adiba Sharipova (piano)/Z. Khaknazirov/Uzbekistan State Symphony Orchestra ( + Zakirov: Piano Concerto and Yanov-Yanovsky: Piano Concertino) MELODIYA S10 20999 001 (LP) (1984) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where his composition teacher was Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. Piano Concerto in E minor (1976) Alexander Tutunov (piano)/ Marlan Carlson/Corvallis-Oregon State University Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Trio, Aria for Viola and Piano and 10 Romances) ALTARUS 9058 (2003) Aria for Violin and Chamber Orchestra (1973) Mikhail Shtein (violin)/Alexander Polyanko/Minsk Chamber Orchestra ( + Vagner: Clarinet Concerto and Alkhimovich: Concerto Grosso No. 2) MELODIYA S10 27829 003 (LP) (1988) MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Concertos A-G ISIDOR ACHRON (1891-1948) Piano Concerto No.