The American Progressive Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upton Sinclair Against Capitalism

Scientific Journal in Humanities, 1(1):41-46,2012 ISSN:2298-0245 Walking Through The Jungle: Upton Sinclair Against Capitalism George SHADURI* Abstract At the beginning of the 20th century, the American novel started exploring social themes and raising social problems. Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle, which appeared in 1906, was a true sensation for American reading community. On the one hand, it described the outra- geous practices of meatpacking industry prevalent at those times on the example of slaughterhouses in Chicago suburbs; on the other hand, it exposed the hapless life of American worker: the book showed what kind of suffering the worker experienced from his thankless work and poor living conditions. Sinclair hoped that the novel, which was avidly read both in America and abroad, would help improve the plight of American worker. However, to his disappointment, the government and society focused their attention exclusively on unhealthy meatpacking practices, which brought about necessary, but still superficial reforms, ignoring the main topic: the life of the common worker. Sinclair was labeled “a muckraker”, whereas he in reality aspired for the higher ideal of changing the existing social order, the thought expressed both in his novels and articles. The writer did not take into account that his ideas of non-violent, but drastic change of social order were alien for American society, for which capitalism was the most natural and acceptable form of functioning. The present article refers to the opinions of both American and non-American scholars to explain the reasons for the failure of Sinclair’s expectations, and, based on their views, concludes why such a failure took place. -

Anarchy! an Anthology of Emma Goldman's Mother Earth

U.S. $22.95 Political Science anarchy ! Anarchy! An Anthology of Emma Goldman’s MOTHER EARTH (1906–1918) is the first An A n t hol o g y collection of work drawn from the pages of the foremost anarchist journal published in America—provocative writings by Goldman, Margaret Sanger, Peter Kropotkin, Alexander Berkman, and dozens of other radical thinkers of the early twentieth cen- tury. For this expanded edition, editor Peter Glassgold contributes a new preface that offers historical grounding to many of today’s political movements, from liber- tarianism on the right to Occupy! actions on the left, as well as adding a substantial section, “The Trial and Conviction of Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman,” which includes a transcription of their eloquent and moving self-defense prior to their imprisonment and deportation on trumped-up charges of wartime espionage. of E m m A g ol dm A n’s Mot h er ea rt h “An indispensable book . a judicious, lively, and enlightening work.” —Paul Avrich, author of Anarchist Voices “Peter Glassgold has done a great service to the activist spirit by returning to print Mother Earth’s often stirring, always illuminating essays.” —Alix Kates Shulman, author of Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen “It is wonderful to have this collection of pieces from the days when anarchism was an ism— and so heady a brew that the government had to resort to illegal repression to squelch it. What’s more, it is still a heady brew.” —Kirkpatrick Sale, author of The Dwellers in the Land “Glassgold opens with an excellent brief history of the publication. -

THE JUNGLE by VICTORIA ALLEN, M.Ed

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO THE SIGNET CLASSIC EDITION OF UPTON SINCLAIR’S THE JUNGLE By VICTORIA ALLEN, M.Ed. SERIES EDITORS: W. GEIGER ELLIS, ED.D., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, EMERITUS and ARTHEA J. S. REED, PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, RETIRED A Teacher’s Guide to the Signet Classic Edition of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle 2 INTRODUCTION The Jungle by Upton Sinclair was written at the turn of the twentieth century. This period is often painted as one of advancement of the human condition. Sinclair refutes this by unveiling the horrible injustices of Chicago’s meat packing industry as Jurgis Rudkus, his protagonist, discovers the truth about opportunity and prosperity in America. This book is a good choice for eleventh and twelfth grade, junior college, or college students mature enough to understand the purpose of its content. The “hooks” for most students are the human-interest storyline and the graphic descriptions of the meat industry and the realities of immigrant life in America. The teacher’s main role while reading this book with students is to help them understand Sinclair’s purpose. Coordinating the reading of The Jungle with a United States history study of the beginning of the 1900s will illustrate that this novel was not intended as mere entertainment but written in the cause of social reform. As students read, they should be encouraged to develop and express their own ideas about the many political, ethical, and personal issues addressed by Sinclair. This guide includes an overview, which identifies the main characters and summarizes each chapter. -

November 1976• Volume I, No

IS THIS DEVICE THE NEW THALIDOMIDE? Its storyis clearly (cont.p.36) [ADVERTISEMENT] Please enclose checkor money orderto: QUEST: A FEMINISTQUARTERLY P.O. Box 8843 Washington,D.C. 20003 $900/year (4 issues) individuals $2.75 & .35(postage & handling) samplecopy $17.00/two years Name Address __________________ City State Zin MOTHER A MAGAZINE FOR THE REST OF US JONES NOVEMBER 1976• VOLUME I, NO. VIII FRONTLINES FEATURES ______________ ____ Page 5 Page 14 NEWS: D. B. Cooper, you can come in MINE THE MOON, from the cold; how to avoid paying taxes SEED THE STARS on bribe income; theTop Ten albums of all by Don Goldsmith time (no, not the Beatles or the Stones); Hello up there, Timothy Leary. What's the city that's still battling big oil. this new planof yours for getting us all into space colonies? Page 21 THE NEXT SIX VIETNAMS by Roger Rapoport The U.S. has been involved in 17 wars or military interventions since Pearl Harbor. Here's our educated guess at where some of the next 17 will be—and how they'llbe differentfrom any wars we've known so far. Page27 Werner is the kind of THE BOAT par heuser, Herzog GLASS-BOTrOMED personwho gives rise to legends. François by Paul West Truffaut considers him "the film- "It when out in the greatest began TobyFlankers, makeralive and working today." middle of Montego Bay in his glass-bot- tomed boat with two tourists, all of a sudden beganto stampbarefoot on one of THE ARTS COVER STORY the two panels." A shortstory. -

A Rip in the Social Fabric: Revolution, Industrial Workers of the World, and the Paterson Silk Strike of 1913 in American Literature, 1908-1927

i A RIP IN THE SOCIAL FABRIC: REVOLUTION, INDUSTRIAL WORKERS OF THE WORLD, AND THE PATERSON SILK STRIKE OF 1913 IN AMERICAN LITERATURE, 1908-1927 ___________________________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ___________________________________________________________________________ by Nicholas L. Peterson August, 2011 Examining Committee Members: Daniel T. O’Hara, Advisory Chair, English Philip R. Yannella, English Susan Wells, English David Waldstreicher, History ii ABSTRACT In 1913, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) led a strike of silk workers in Paterson, New Jersey. Several New York intellectuals took advantage of Paterson’s proximity to New York to witness and participate in the strike, eventually organizing the Paterson Pageant as a fundraiser to support the strikers. Directed by John Reed, the strikers told their own story in the dramatic form of the Pageant. The IWW and the Paterson Silk Strike inspired several writers to relate their experience of the strike and their participation in the Pageant in fictional works. Since labor and working-class experience is rarely a literary subject, the assertiveness of workers during a strike is portrayed as a catastrophic event that is difficult for middle-class writers to describe. The IWW’s goal was a revolutionary restructuring of society into a worker-run co- operative and the strike was its chief weapon in achieving this end. Inspired by such a drastic challenge to the social order, writers use traditional social organizations—religion, nationality, and family—to structure their characters’ or narrators’ experience of the strike; but the strike also forces characters and narrators to re-examine these traditional institutions in regard to the class struggle. -

Progressive Era 1900-1917

Urban America and the Progressive Era 1900-1917 I. American Communities A. The Henry Street Settlement House II. The Origins of Progressivism A. Characteristics and Goals B. Unifying Themes C. New Journalism: Muckraking 1. Jacob Riis: How the Other Half Lives 2. Large-circulation Magazines: McClure's 3. Lincoln Steffens: The Shame of the Cities 4. Ida Tarbell: History of the Standard Oil Company 5. Upton Sinclair: The Jungle 6. David Graham Phillips: The Treason of the Senate 7. TR: "muckrakers" D. Intellectual Trends Promoting Reform 1. Emergence of social sciences 2. John Dewey: "creative intelligence" 3. The Fourteenth Amendment a. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. 4. Muller v. Oregon (1908) E. The Female Dominion 1. Settlement houses 2. Jane Addams and Florence Kelley III. Progressive Politics in Cities and States A. The Urban Machine 1. Democratic party machines a. Irish in cities B. Progressives and Urban Reform 1. Political machinery and Urban conditions F. Statehouse Progressives: West and South 1. Robert M. LaFollette 2. Direct Democracy a. Initiative, referendum, recall 3. Southern Progressivism a. Segregation & Disfranchisement: African Americans b. Big Business & "unruly citizens" c. Child labor laws & Compulsory education III. Social Control and Its Limits A. The Prohibition Movement 1. Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) 2. The Anti-Saloon League 3. "Pietists" v. "Ritualists" B. The Social Evil 1. Prostitution and "White slave traffic" C. The Redemption of Leisure 1. "Commercialized Leisure" 2. Movies and the National Board of Censorship D. Standardizing Education 1. Public Schools: Americanization 2. Compulsory school attendance IV . Challenges to Progessivism A. The New Global Immigration 1. -

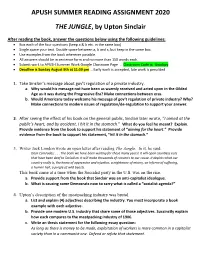

Apush Summer Reading Assignment 2020 the Jungle

APUSH SUMMER READING ASSIGNMENT 2020 THE JUNGLE, by Upton Sinclair After reading the book, answer the questions below using the following guidelines: • Box each of the four questions (keep a & b etc. in the same box) • Single space your text. Double space between a, b and c, but keep in the same box. • Use examples from the book wherever possible. • All answers should be in sentence form and no more than 150 words each. • Submit work to APUSH Summer Work Google Classroom Page … Classroom Code is: 6wolqzy • Deadline is Sunday August 9th at 11:59 pm … Early work is accepted, late work is penalized 1. Take Sinclair’s message about gov’t regulation of a private industry. a. Why would his message not have been as warmly received and acted upon in the Gilded Age as it was during the Progressive Era? Make connections between eras. b. Would Americans today welcome his message of gov’t regulation of private industry? Why? Make connections to modern issues of regulation/de-regulation to support your answer. 2. After seeing the effect of his book on the general public, Sinclair later wrote, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident, I hit it in the stomach.” What do you feel he meant? Explain. Provide evidence from the book to support his statement of “aiming for the heart.” Provide evidence from the book to support his statement, “hit it in the stomach.” 3. Writer Jack London wrote an open letter after reading The Jungle. In it, he said: Dear Comrades: . The book we have been waiting for these many years! It will open countless ears that have been deaf to Socialism. -

The Problem with Classroom Use of Upton Sinclair's the Jungle

The Problem with Classroom Use of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle Louise Carroll Wade There is no doubt that The Jungle helped shape American political history. Sinclair wrote it to call attention to the plight of Chicago packinghouse workers who had just lost a strike against the Beef Trust. The novel appeared in February 1906, was shrewdly promoted by both author and publisher, and quickly became a best seller. Its socialist message, however, was lost in the uproar over the relatively brief but nauseatingly graphic descriptions of packinghouse "crimes" and "swindles."1 The public's visceral reaction led Senator Albert Beveridge of Indiana to call for more extensive federal regulation of meat packing and forced Congress to pay attention to pending legislation that would set government standards for food and beverages. President Theodore Roosevelt sent two sets of investigators to Chicago and played a major role in securing congressional approval of Beveridge's measure. When the President signed this Meat Inspec tion Act and also the Food and Drugs Act in June, he graciously acknowledged Beveridge's help but said nothing about the famous novel or its author.2 Teachers of American history and American studies have been much kinder to Sinclair. Most consider him a muckraker because the public^responded so decisively to his accounts of rats scurrying over the meat and going into the hoppers or workers falling into vats and becoming part of Durham's lard. Many embrace The Jungle as a reasonably trustworthy source of information on urban immigrant industrial life at the turn of the century. -

Open Letter to the Members of the Socialist Party, May 17, 1908 by Eugene V

Open Letter to the Members of the Socialist Party, May 17, 1908 by Eugene V. Debs Published as “Our Presidential Candidate” in St. Louis Labor, vol. 6, whole no. 381 (May 23, 1908), pg. 2. Girard, Kan., May 17, 1908. Comrades:— The honor of the Presidential nomination has come to me through no fault of my own. It has been said that some men are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.1 It is even so with what are called honors. Some men have honors thrust upon them. I find myself in that class. I did what little I could to prevent myself from being nominated by the convention now in session at Chicago, but the nomination sought me out, and in spite of myself I stand in your presence this afternoon the nominee of the Socialist Party for the Presidency of the United States. Lon, long ago I made up my mind never again to be a candidate for any politi- cal office within the gift of the people. I was constrained to violate that vow because when I joined the Socialist Party I was taught that the desire of the individual was subordinate to the party will, and that when the party commanded it was my duty to obey. There was a time in my life when I had the vanities of youth, when I sought that bubble called fame. I have outlived it. I have reached that point when I am capable of placing an estimate upon my own relative insignificance. -

Helen Keller ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Story of HELEN KELLER ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ In Grateful Memory of Teacher ... Who led a little girl out of the dark And gave to the world ... Helen Keller 1 CONTENTS 1. Little Girl in the Dark 2. The Stranger 3. Helen Has a Tantrum 4. The Word Game 5. W-A-T-E-R 6. Everything Has a Name! 7. Learning Is Fun 8. Helen Writes a Letter 9. Another Way of Writing 10. "A Lion Has a Big Purr!" 11. Most Famous Child in the World 12. Winter in the Snow 13. "I Am Not Dumb Now!" 14. Little Tommy Stringer 15. "I Am Going to Harvard" 16. A Dream Comes True 17. "I Must Earn My Living" 18. Narrow Escape 19. Behind the Footlights 20. The Teacher Book 21. One Summer Day CHAPTER ONE - Little Girl in the Dark It was a warm summer evening in the sleepy little town of Tuscumbia, Alabama. A light breeze rustled through the ivy leaves and brought the fragrance of roses into the living room of the vine- covered Keller house. Captain Arthur Keller laid down his newspaper and peered thoughtfully over his glasses at his six-year-old daughter Helen, curled up in a chair with a big, shapeless rag doll. "Her mind-whatever mind she has−is locked up in a prison cell," he said sadly. "It can't get out, and nobody can open the door to reach it. For the key is lost and nobody can find it." Helen's mother looked up from her sewing. Tears filled her eyes. -

The Odd Amalgam: John L. Spivak's 1932 Photographs, Undercover Reporting, and Fiction in Georgia Nigger Ronald E. Ostman Depa

The Odd Amalgam: John L. Spivak’s 1932 Photographs, Undercover Reporting, and Fiction in Georgia Nigger Ronald E. Ostman Department of Communication Cornell University and Berkley Hudson School of Journalism University of Missouri-Columbia Paper presented to the Visual Studies Division International Communication Association Dresden, Germany June 20, 2006 Lincoln Steffens (1866-1936), who generally is cited as the first muckraking journalist, called John L. Spivak (1897-1981) “the best of us.” Spivak, among many progressive and muckraking writers of America’s early 20th century who might have competed for the honor, was labeled by some of his contemporaries as “the best reporter … in the whole United States at the present moment,” “America’s greatest newspaper man,” “one of the alertest reporters alive,” and “greatest reporter since Lincoln Steffens” (Florinsky, 1936). Spivak, Who? Yet today Spivak is almost unknown among journalism and communication historians and scholars. Perhaps this neglect is due to his ideology. He began as a socialist, was quickly disillusioned, and became a thinly disguised communist (Goode, 1997; Gross, 1935). He was blacklisted during the McCarthy era of suppression and was imprisoned several times for his alleged libelous writings. Or, perhaps his current neglect is due to his many violations of ethical standards (by today’s standards) in the ways he went about investigating and reporting. Or maybe he’s been forgotten because he did not report exclusively for the “objective” mainstream newspapers of the era, often preferring instead such outlets as the communistic Daily Worker, the leftist New Masses, the short-lived exposé magazine Ken, the New Haven Union (CT), the socialistic Call, the Charleston Gazette (WV), trashy pulp magazines like True Strange Stories, and the like (North, 1969). -

• How Did Upton Sinclair the Entire Food Industry?

• R.A.W •AIM: • How did Upton Sinclair change/reform/progress the entire food industry? • Ha I aimed for Americas heart and I hit them in the stomach --U. Sinclair I. The Jungle • Written by Upton Sinclair in 1906. • Written to show Americans how immigrants were treated in Chicago meat packing factories. • People will be outraged over the food. II. Reform • The Meat Inspection Act.(1906) • Sets up system of random food inspection. • Pure Food and Drug Act.(1906) • Sets up FDA, Food and Drug Administration. • Requires all food to be properly labeled. • Bans the sale of harmful food and medicine. There were the men in the pickle rooms, for instance, where old Antanas had gotten his death; scarce a one of these that had not some spot of horror on his person. Let a man so much as scrape his finger pushing a truck in the pickle rooms, and he might have a sore that would put him out of the world; all the joints in his fingers might be eaten by the acid, one by one. Of the butchers and floorsmen, the beef-boners and trimmers, and all those who used knives, you could scarcely find a person who had the use of his thumb; time and time again the base of it had been slashed, till it was a mere lump of flesh against which the man pressed the knife to hold it. The hands of these men would be criss- crossed with cuts, until you could no longer pretend to count them or to trace them.