For the Full Story (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel-Hizbullah Conflict: Victims of Rocket Attacks and IDF Casualties July-Aug 2006

My MFA MFA Terrorism Terror from Lebanon Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket attacks and IDF casualties July-Aug 2006 Search Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket E-mail to a friend attacks and IDF casualties Print the article 12 Jul 2006 Add to my bookmarks July-August 2006 Since July 12, 43 Israeli civilians and 118 IDF soldiers have See also MFA newsletter been killed. Hizbullah attacks northern Israel and Israel's response About the Ministry (Note: The figure for civilians includes four who died of heart attacks during rocket attacks.) MFA events Foreign Relations Facts About Israel July 12, 2006 Government - Killed in IDF patrol jeeps: Jerusalem-Capital Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Eyal Benin, 22, of Beersheba Treaties Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Shani Turgeman, 24, of Beit Shean History of Israel Sgt.-Maj. Wassim Nazal, 26, of Yanuah Peace Process - Tank crew hit by mine in Lebanon: Terrorism St.-Sgt. Alexei Kushnirski, 21, of Nes Ziona Anti-Semitism/Holocaust St.-Sgt. Yaniv Bar-on, 20, of Maccabim Israel beyond politics Sgt. Gadi Mosayev, 20, of Akko Sgt. Shlomi Yirmiyahu, 20, of Rishon Lezion Int'l development MFA Publications - Killed trying to retrieve tank crew: Our Bookmarks Sgt. Nimrod Cohen, 19, of Mitzpe Shalem News Archive MFA Library Eyal Benin Shani Turgeman Wassim Nazal Nimrod Cohen Alexei Kushnirski Yaniv Bar-on Gadi Mosayev Shlomi Yirmiyahu July 13, 2006 Two Israelis were killed by Katyusha rockets fired by Hizbullah: Monica Seidman (Lehrer), 40, of Nahariya was killed in her home; Nitzo Rubin, 33, of Safed, was killed while on his way to visit his children. -

3 Merhavia (1921–1925)

3 Merhavia (1921–1925) Almost from the moment she set foot in dusty, hot and humid Tel Aviv, Golda was determined to leave the cluster of small yellow buildings, unpaved streets and and sand dunes that tried to pass as the world’s “first Hebrew city”, and fulfill her dream of living on a kibbutz. She jokingly echoed the general feeling that instead of milk and honey there was plenty of sand. She had a vague idea of what life on a kibbutz would be like, how it was organized and functioned. What she knew was more of a myth than the harsh reality, but enough to convince her that this should be the life for a young and idealistic couple. Perhaps one of the main errors committed by Golda and her group was to immigrate to Palestine without even seeking the moral, organizational and mainly financial backing of a large social and political body. Since they came on their own, nobody felt any moral obligation to look after their needs, offer assis- tance and suggest job and housing possibilities in the new country. Golda and her friends were not aware of the fact that they were part of what became known as the Third Aliyah (wave of immigration to Palestine) which started in 1919 and ended in the mid 1920’s. They followed in the footsteps of the Second Aliyah (1904–1914), whose members were the founding fathers of Israel, men who would play a key role in Golda’s future work and private life. Among them were David Ben-Gurion, Berl Katznelson, David Remez and Zalman Shazar. -

Reflections of Children in Holocaust Art (Essay) Josh Freedman Pnina Rosenberg 98 Shoshana (Poem) 47 the Blue Parakeet (Poem) Reva Sharon Julie N

p r an interdisciplinary journal for holocaust educators • a rothman foundation publication ism • an interdisciplinary journal for holocaust educators AN INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL FOR HOLOCAUST EDUCATORS E DITORS: DR. KAREN SHAWN, Yeshiva University, NY, NY DR. JEFFREY GLANZ, Yeshiva University, NY, NY EDITORIAL BOARD: DARRYLE CLOTT, Viterbo University, La Crosse, WI yeshiva university • azrieli graduate school of jewish education and administration DR. KEREN GOLDFRAD, Bar-Ilan University, Israel BRANA GUREWITSCH, Museum of Jewish Heritage– A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, NY, NY DR. DENNIS KLEIN, Kean University, NJ DR. MARCIA SACHS LiTTELL, School of Graduate Studies, The Richard Stockton College of New Jersey DR. ROBERT ROZETT, Yad Vashem DR. DAVID ScHNALL, Yeshiva University, NY, NY DR. WiLLIAM SHULMAN, Director, Association of Holocaust Organizations DR. SAMUEL TOTTEN, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville DR. WiLLIAM YOUNGLOVE, California State University Long Beach ART EDITOR: DR. PNINA ROSENBERG, Ghetto Fighters’ Museum, Western Galilee POETRY EDITOR: DR. CHARLES AdÉS FiSHMAN, Emeritus Distinguished Professor, State University of New York ADVISORY BOARD: STEPHEN FEINBERG, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum DR. HANITA KASS, Educational Consultant DR. YAACOV LOZOWICK, Historian YITZCHAK MAIS, Historian, Museum Consultant GERRY MELNICK, Kean University, NJ RABBI DR. BERNHARD ROSENBERG, Congregation Beth-El, Edison; NJ State Holocaust Commission member MARK SARNA, Second Generation, Real Estate Developer, Attorney DR. DAVID SiLBERKLANG, Yad Vashem SIMCHA STEIN, Ghetto Fighters’ Museum, Western Galilee TERRI WARMBRAND, Kean University, NJ fall 2009 • volume 1, issue 1 DR. BERNARD WEINSTEIN, Kean University, NJ DR. EFRAIM ZuROFF, Simon Wiesenthal Center, Jerusalem AZRIELI GRADUATE SCHOOL DEPARTMENT EDITORS: DR. SHANI BECHHOFER DR. CHAIM FEUERMAN DR. ScOTT GOLDBERG DR. -

Jerusalemhem QUARTERLY MAGAZINE, VOL

Yad VaJerusalemhem QUARTERLY MAGAZINE, VOL. 53, APRIL 2009 New Exhibit: The Republic of Dreams Bruno Schulz: Wall Painting Under Coercion (p. 4) ChildrenThe Central Theme forin Holocaust the RemembranceHolocaust Day 2009 (pp. 2-3) Yad VaJerusalemhem QUARTERLY MAGAZINE, VOL. 53, Nisan 5769, April 2009 Published by: Yad Vashem The Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority Children in the Holocaust ■ Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Vice Chairmen of the Council: Dr. Yitzhak Arad Contents Dr. Israel Singer Children in the Holocaust ■ 2-3 Professor Elie Wiesel ■ On Holocaust Remembrance Day this year, The Central Theme for Holocaust Martyrs’ Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev during the annual “Unto Every Person There and Heroes’ Remembrance Day 2009 Director General: Nathan Eitan is a Name” ceremony, we will read aloud the Head of the International Institute for Holocaust New Exhibit: names of children murdered in the Holocaust. Research: Professor David Bankier The Republic of Dreams ■ 4 Some faded photographs of a scattered few Chief Historian: Professor Dan Michman Bruno Schulz: Wall Painting Under Coercion remain, and their questioning, accusing eyes Academic Advisors: cry out on behalf of the 1.5 million children Taking Charge ■ 5 Professor Yehuda Bauer prevented from growing up and fulfilling their Professor Israel Gutman Courageous Nursemaids in a Time of Horror basic rights: to live, dream, love, play and Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Education ■ 6-7 laugh. Shlomit Amichai, Edna Ben-Horin, New International Seminars Wing Chaim Chesler, Matityahu Drobles, From the day the Nazis came to power, ,Abraham Duvdevani, ֿֿMoshe Ha-Elion, Cornerstone Laid at Yad Vashem Jewish children became acquainted with cruelty Yehiel Leket, Tzipi Livni, Adv. -

5 Mp 1502 1928

FREE weekly SUPPLEMENT TO OUR REVIEW NO. 102 (1502) APRIL 13, 1928 IN Warsaw. YEAR 2, Nº 80 (ISSN 2544-0187) PaPER FOR CHILDREN AND yoUTH EDITED BY JANUSZ KORCZAK PUBLISHED EVery FRIDay MORNING CORRESPONDENCE AND materials SHOULD BE SENT TO THE LITTLE REVIEW NEWSROOM Warsaw, NO. 7 NOWOLIPKI STREET AN EGYPTIAN PLAGUE MY SCHOOLMATE MENDEL Apart from cigarettes, another overseas kindlekh!” (“Why wouldn’t the guests His name was Mendel and he was for everybody at once to say that they a long time, so that they turn into Egyptian plague has recently fallen deserve to play? Play, kids!”) attending the same school as I was; wanted to be with me, to talk, and to soup. You can cook it with meat, oil, upon the children. Its name: the pin- The boys have lost 50 groszy within he was in the introductory grade and play. The entire school thought that or lard, or put some bones in it, but ball machine. Adults have invented a couple of minutes. And I ask where I was in the first grade. When I came Mendel and I were best friends, but for them just pure salt was enough it and placed it in cinemas and coffee did they have this money from and in for the first time, it was already in reality, we talked with each other because they had none of the things shops. What does it matter that on what was it intended for? after the bell had rung, and you had only a few times, and only when he listed above. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Kibbutz Fiction and Yishuv Society on the Eve of Statehood: the Ma'agalot

The Journal of Israeli History Vol. 31, No. 1, March 2012, 147–165 Kibbutz fiction and Yishuv society on the eve of statehood: The Ma’agalot (Circles) affair of 19451 Shula Keshet* The novel Circles (1945) by David Maletz, a founding member of Kibbutz Ein Harod, created a furor both in kibbutz society and among its readers in the Yishuv. The angry responses raise numerous questions about the status of kibbutz society at the time and the position of the writer in it. This article examines the reasons for the special interest in Maletz’s book and considers its literary qualities. On the basis of the numerous responses to the book, it analyzes how kibbutz society was viewed in that period, both by its own members and by the Yishuv in general, and addresses the special dynamics of the work’s reception in a totally ideological society. The case of Circles sheds light on the ways in which kibbutz literature participated in the ideological construction of the new society, while at the same time criticizing its most basic assumptions from within. Keywords: David Maletz; Berl Katznelson; kibbutz; Hebrew literature; kibbutz literature; Yishuv society; readers’ response; ideological dissent Introduction The novel Circles by David Maletz, a founding member of Kibbutz Ein Harod, created a furor both within and outside kibbutz society upon its publication in 1945, in many ways marking the start of an internal crisis in kibbutz society that erupted in full force only some forty years later, in the late 1980s. Reading this novel in historical perspective provides insight into the roots of this crisis. -

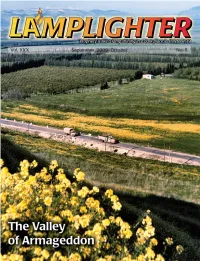

Lamplighter Sep/Oct 2009

Observations by the Editor Armageddon ts ancient biblical name is the valley of IJezreel (Joshua 17:16), meaning “God sows.” That is what modern day Israelis still call it. The Greeks gave it the name, The Lamplighter “the plain of Esdraelon,” which was the is published bi-monthly Greek rendering of Jezreel. It is referred by Lamb & Lion Ministries to in Joel 3:2 as the valley of Jehosha- Mailing Address: phat, meaning the “valley of Judgment.” P.O. Box 919 Ann Reagan overlooking the valley of McKinney, TX 75070 When I take pilgrim groups to Israel, their first sight of the valley occurs on the Armageddon from the roof of the Mount Carmel Monastery. Telephone: 972/736-3567 second day of touring when we go to the Fax: 972/734-1054 traditional site on Mount Carmel where Sales: 1-800/705-8316 Turkish army in September 1918, com- Email: [email protected] the prophet Elijah confronted the proph- pleting his conquest of the Middle East Website: www.lamblion.com ets of Baal. We climb some steep stairs for the Allied Forces in World War I. that lead to the flat-top roof of a monas- b b b b b b b b b tery, and as soon as people arrive on the As early as 1891 the man who would Chairman of the Board: roof and turn around to face the valley, later be known as the “Redeemer of the Jerry Lauer there is always a tremendous shout of Valley,” Yehoshua Hankin, began nego- tiating for the purchase of 40,000 acres. -

Germs Know No Racial Lines: Health Policies in British Palestine (1930

UNIVERSITY OT LONDON University College London Marcella Simoni “Germs know no racial lines” Health policies in British Palestine (1930-1939) Thesis submitted for the degree of goctor of Philosophy 2003 ProQuest Number: U642896 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642896 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract In mandatory Palestine, Zionist civil society proved to be a powerful instrument for institution- and state-building. Civil society developed around four conditions: shared values, horizontal linkages of participation, boundary demarcation and interaction with the state. These four 6ctors were created and/or enhanced by the provision of medical services and by the organization of public health. In Jewish Palestine, these were developed - especially in the 1930s - by two medical agencies: the Hadassah Medical Organization and Kupat Cholim. First of all, Zionist health developed autonomously from an administrative point of view. Secondly, it was organized in a network of horizontal participation which connect different sections of the (Jewish) population. In the third place, medical provision worked as a connecting element between territory, society and administratioiL Lastly, the construction of health in mandatory Palestine contributed to create a cultural uniformity which was implicitly nationalistic. -

Infrastructure for Growth 2020 Government of Israel TABLE of CONTENTS

Infrastructure for Growth 2020 Government of Israel TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Acting Director-General, Prime Minister’s Office, Ronen Peretz ............................................ 3 Reader’s Guide ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Summary of infrastructure projects for the years 2020-2024 Ministry of Transportation and Road Safety ................................................................................................ 8 Ministry of Energy ...................................................................................................................................... 28 Ministry of Water Resources ....................................................................................................................... 38 Ministry of Finance ..................................................................................................................................... 48 Ministry of Defense .................................................................................................................................... 50 Ministry of Health ...................................................................................................................................... 53 Ministry of Environmental Protection ......................................................................................................... 57 Ministry of Education ................................................................................................................................ -

Supplement Ißo. 2. to Gbe Ipaleôttne C&^Ette Ißo. 565 of 23Rt> January

Supplement ißo. 2. to Gbe ipaleôttne C&^ette ißo. 565 of 23rt> January 1936. EXPROPRIATION OF LAND ORDINANCES, 1926-1935. CERTIFICATE I, LIEUTENANT-GENERAL SIR ARTHUR GREXFELL WAUCHOPE, High Commissioner for Palestine, hereby certify that the construction ol Police Married Quarters is an undertaking of a public nature within the meaning of the Expropriation of Land Ordinances, 1926-1935. A plan of the selected site is deposited at the offices of the District Commis• sioner, Jerusalem District, and the Director of Land Registration, Jerusalem. A. G. WAUCHOPE 15th January, 1936. High Commissioner. (L/6/36) CUSTOMS ORDINANCE, 1929. NOTICE IT IS HEREBY NOTIFIED by His Excellency the High Commissioner in accord• ance with paragraph 25 of the Regulations under the Customs Ordinance, — 35 — d929, which were published in the Gazette Extraordinary of the 15th clay of March, 1929, that the warehouse of Messrs. The Near East Bonded Warehouses Company Ltd., Haifa, situated at Haifa on Plot No. 7 of the Haifa Harbour Reclaimed Area, has been approved as a General Bonded Warehouse with effect from the 1st January, 1936. By His Excellency's Command, J. HATHORN HALL 15th January, 1936. Chief Secretary. (C/589/33) PORTS ORDINANCE, 1926. ORDER BY THE HIGH COMMISSIONER UNDER SECTION 10 (1). IN EXERCISE of the powers vested in him by sub-section (1) No. 10 of 1926. of section 10 of the Ports Ordinance, 1926, the High Commissioner is pleased to order and it is hereby ordered as follows:— Citation. 1. This Order may be cited as the Haifa .Port (Variation of Tariff of Charges) Order, 1936. -

Land Transformation in Israel

- ~~-~-U-.m --~-~ ~- ~--- Land Transformation in Agriculture Edited by M. G. Wolman and F. G. A. Fournier @ 1987 SCOPE. Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd CHAPTER 8 Land Transformation in Israel D. H. K. AMIRAN 8.1 INTRODUCTION The countries around the Mediterranean have experienced far-reaching changes in land quality and land use. The centres of very early, highly developed civilizations of the western world were here. Together with their great achievements they brought about intensive use of the land-sometimes exceSSIveuse. The political changes that affected the area during a millennia of its history involved similar changes, for better or for worse, in husbanding of the land. Extensive areas of olive groves-famous since antiquity-fruit orchards and vineyards, many of them grown on carefully terraced slopes, indicate but some of the prominent achievements of mediterranean agriculture. By con- trast, periods of decline, being sometimes periods of depopulation, brought about very adverse effects, in particular abandonment of cultivated land and disrepair of the terraces. In consequence there was erosion of the soil, and downwash into the valleys of the lowland plains; there was excessive sedimen- tation in these valleys, choking the river and wadi beds, and sometimes followed by formation of swamps owing to lack of drainage; and not infre- quently malaria affected these swampy areas. This whole syndrome of land deterioration is illustrated in many mediterranean countries. A classic case is Israel of the nineteenth century. Israel showed some significant achievements in agriculture and land development in antiquity, and the deterioration is easy to follow in detail. Two factors bring about particu- larly significant effects of processes of land transformation.