Land Transformation in Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mediterranean Coast of Israel Is a New City,Now Under

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Theses and Major Papers Marine Affairs 12-1973 The editM erranean Coast of Israel: A Planner's Approach Sophia Professorsky University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/ma_etds Part of the Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Recommended Citation Professorsky, Sophia, "The eM diterranean Coast of Israel: A Planner's Approach" (1973). Theses and Major Papers. Paper 146. This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Marine Affairs at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Major Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. l~ .' t. ,." ,: .. , ~'!lB~'MEDI'1'ERRANEAN-GQAsT ~F.~"IsMt~·;.·(Al!~.oS:-A~PROACH ::".~~========= =~.~~=~~~==b======~~==~====~==.=~=====~ " ,. ••'. '. ,_ . .. ... ..p.... "".. ,j,] , . .;~ ; , ....: ./ :' ",., , " ",' '. 'a ". .... " ' ....:. ' ' .."~".,. :.' , v : ".'. , ~ . :)(A;R:t.::·AF'~~RS'· B~NMi'»APER. '..":. " i . .: '.'-. .: " ~ . : '. ". ..." '-" .~" ~-,.,. .... .., ''-~' ' -.... , . ", ~,~~~~"ed .' bYr. SOph1a,Ji~ofes.orsJcy .. " • "..' - 01 .,.-~ ~ ".··,::.,,;$~ld~~:' ·to,,:" f;~f.... ;)J~:Uexa~d.r . -". , , . ., .."• '! , :.. '> ...; • I ~:'::':":" '. ~ ... : .....1. ' ..~fn··tr8Jti~:·'btt·,~e~Mar1ne.~a1~S·~r~~. ", .:' ~ ~ ": ",~', "-". ~_"." ,' ~~. ;.,·;·X;'::/: u-=" .. _ " -. • ',. ,~,At:·;t.he ,un:lvers:U:~; tif Rh~:<:rs1..J\d. ~ "~.; ~' ~.. ~,- -~ !:).~ ~~~ ~,: ~:, .~ ~ ~< .~ . " . -, -. ... ... ... ... , •• : ·~·J;t.1l9ston.l~~;&:I( .. t)eceiDber; 1~73.• ". .:. ' -.. /~ NOTES, ===== 1. Prior to readinq this paper, please study the map of the country (located in the back-eover pocket), in order to get acquain:t.ed with names and locations of sites mentioned here thereafter. 2.- No ~eqaJ. aspects were introduced in this essay since r - _.-~ 1 lack the professional background for feedinq in tbe information. -

Israel-Hizbullah Conflict: Victims of Rocket Attacks and IDF Casualties July-Aug 2006

My MFA MFA Terrorism Terror from Lebanon Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket attacks and IDF casualties July-Aug 2006 Search Israel-Hizbullah conflict: Victims of rocket E-mail to a friend attacks and IDF casualties Print the article 12 Jul 2006 Add to my bookmarks July-August 2006 Since July 12, 43 Israeli civilians and 118 IDF soldiers have See also MFA newsletter been killed. Hizbullah attacks northern Israel and Israel's response About the Ministry (Note: The figure for civilians includes four who died of heart attacks during rocket attacks.) MFA events Foreign Relations Facts About Israel July 12, 2006 Government - Killed in IDF patrol jeeps: Jerusalem-Capital Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Eyal Benin, 22, of Beersheba Treaties Sgt.-Maj.(res.) Shani Turgeman, 24, of Beit Shean History of Israel Sgt.-Maj. Wassim Nazal, 26, of Yanuah Peace Process - Tank crew hit by mine in Lebanon: Terrorism St.-Sgt. Alexei Kushnirski, 21, of Nes Ziona Anti-Semitism/Holocaust St.-Sgt. Yaniv Bar-on, 20, of Maccabim Israel beyond politics Sgt. Gadi Mosayev, 20, of Akko Sgt. Shlomi Yirmiyahu, 20, of Rishon Lezion Int'l development MFA Publications - Killed trying to retrieve tank crew: Our Bookmarks Sgt. Nimrod Cohen, 19, of Mitzpe Shalem News Archive MFA Library Eyal Benin Shani Turgeman Wassim Nazal Nimrod Cohen Alexei Kushnirski Yaniv Bar-on Gadi Mosayev Shlomi Yirmiyahu July 13, 2006 Two Israelis were killed by Katyusha rockets fired by Hizbullah: Monica Seidman (Lehrer), 40, of Nahariya was killed in her home; Nitzo Rubin, 33, of Safed, was killed while on his way to visit his children. -

3 Merhavia (1921–1925)

3 Merhavia (1921–1925) Almost from the moment she set foot in dusty, hot and humid Tel Aviv, Golda was determined to leave the cluster of small yellow buildings, unpaved streets and and sand dunes that tried to pass as the world’s “first Hebrew city”, and fulfill her dream of living on a kibbutz. She jokingly echoed the general feeling that instead of milk and honey there was plenty of sand. She had a vague idea of what life on a kibbutz would be like, how it was organized and functioned. What she knew was more of a myth than the harsh reality, but enough to convince her that this should be the life for a young and idealistic couple. Perhaps one of the main errors committed by Golda and her group was to immigrate to Palestine without even seeking the moral, organizational and mainly financial backing of a large social and political body. Since they came on their own, nobody felt any moral obligation to look after their needs, offer assis- tance and suggest job and housing possibilities in the new country. Golda and her friends were not aware of the fact that they were part of what became known as the Third Aliyah (wave of immigration to Palestine) which started in 1919 and ended in the mid 1920’s. They followed in the footsteps of the Second Aliyah (1904–1914), whose members were the founding fathers of Israel, men who would play a key role in Golda’s future work and private life. Among them were David Ben-Gurion, Berl Katznelson, David Remez and Zalman Shazar. -

M O J a V E D E S E R T I S S U E S a Secondary

MOJAVE DESERT ISSUES A Secondary School Curriculum Bruce W. Bridenbecker & Darleen K. Stoner, Ph.D. Research Assistant Gail Uchwat Mojave Desert Issues was funded with a grant from the National Park �� Foundation. Parks as Classrooms is the educational program of the National ����� �� ���������� Park Service in partnership with the National Park Foundation. Design by Amy Yee and Sandra Kaye Published in 1999 and printed on recycled paper ii iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks to the following people for their contribution to this work: Elayn Briggs, Bureau of Land Management Caryn Davidson, National Park Service Larry Ellis, Banning High School Lorenza Fong, National Park Service Veronica Fortun, Bureau of Land Management Corky Hays, National Park Service Lorna Lange-Daggs, National Park Service Dave Martell, Pinon Mesa Middle School David Moore, National Park Service Ruby Newton, National Park Service Carol Peterson, National Park Service Pete Ricards, Twentynine Palms Highschool Kay Rohde, National Park Service Dennis Schramm, National Park Service Jo Simpson, Bureau of Land Management Kirsten Talken, National Park Service Cindy Zacks, Yucca Valley Highschool Joe Zarki, National Park Service The following specialists provided information: John Anderson, California Department of Fish & Game Dave Bieri, National Park Service �� John Crossman, California Department of Parks and Recreation ����� �� ���������� Don Fife, American Land Holders Association Dana Harper, National Park Service Judy Hohman, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Becky Miller, California -

December 2017

AUSTRALIA December 2017 www.c4israel.com.au [email protected] AUSTRALIA HAPPY HANUKKAH Blessed are You, Lord our God, Ruler of the universe, who has sanctified us with Your commandments, and has commanded us to kindle the lights of Hanukkah. 3 5 8 6 Highlights... Editorial Pg 2 Hanukkah and Christmas Pg 8 The Battle for Jerusalem Pg 3 Women and Their Olive Trees Pg 9 Rev. Glashouwer Visits Brazil Pg 5 Return from India - A Dream Fulfilled Pg 11 New Israel Centre - Nijkerk Pg 6 “Thank You For Not Forgetting Us” Pg 11 9 11 Christian Media Summit in Israel Pg 7 Israel & Christians Today is the premier publication of Christians for Israel Editorial December 2017 02 Kislev - Tevet 5778 Prayer Points Jerusalem in the ‘End Times’ By Pieter Bénard By Andrew Tucker, International Editor & Executive Director, Christians for Israel International Christians for Israel Prayer Yet God is calling the church of the end and all nations will stream to it”. And in Coordinator times to put on eye salve (Revelation 3), so verse 3: “the law will go out from Zion, the that we may truly understand the signs of word of the Lord from Jerusalem. He will the coming of Jesus. judge between the nations and will settle There are many prophecies in the Bible disputes from many peoples. They will beat concerning Jerusalem. Zechariah 12 verse 2: their swords into ploughshares, and their “I am going to make Jerusalem a cup that spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not sends all the surrounding peoples reeling”. -

Introduction Really, 'Human Dust'?

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Peck, The Lost Heritage of the Holocaust Survivors, Gesher, 106 (1982) p.107. 2. For 'Herut's' place in this matter, see H. T. Yablonka, 'The Commander of the Yizkor Order, Herut, Shoa and Survivors', in I. Troen and N. Lucas (eds.) Israel the First Decade, New York: SUNY Press, 1995. 3. Heller, On Struggling for Nationhood, p. 66. 4. Z. Mankowitz, Zionism and the Holocaust Survivors; Y. Gutman and A. Drechsler (eds.) She'erit Haplita, 1944-1948. Proceedings of the Sixth Yad Vas hem International Historical Conference, Jerusalem 1991, pp. 189-90. 5. Proudfoot, 'European Refugees', pp. 238-9, 339-41; Grossman, The Exiles, pp. 10-11. 6. Gutman, Jews in Poland, pp. 65-103. 7. Dinnerstein, America and the Survivors, pp. 39-71. 8. Slutsky, Annals of the Haganah, B, p. 1114. 9. Heller The Struggle for the Jewish State, pp. 82-5. 10. Bauer, Survivors; Tsemerion, Holocaust Survivors Press. 11. Mankowitz, op. cit., p. 190. REALLY, 'HUMAN DUST'? 1. Many of the sources posed problems concerning numerical data on immi gration, especially for the months leading up to the end of the British Mandate, January-April 1948, and the first few months of the state, May August 1948. The researchers point out that 7,574 immigrant data cards are missing from the records and believe this to be due to the 'circumstances of the times'. Records are complete from September 1948 onward, and an important population census was held in November 1948. A parallel record ing system conducted by the Jewish Agency, which continued to operate after that of the Mandatory Government, provided us with statistical data for immigration during 1948-9 and made it possible to analyse the part taken by the Holocaust survivors. -

Agriculture in Israel Where R&D Meets Nation Needs Itzhak Ben-David

State of Israel Ministry of Agriculture & Rural Development Agriculture in Israel Where R&D Meets Nation Needs Itzhak Ben-David Deputy Director General (Foreign Trade), Sacramento (CA)., May 25, 2017 1 Basic Facts about Israel Population: 8,309,400 Area: 22,000 km2 GDP Agriculture 12.6 Billion NIS - 1.4% Employment in Agriculture about 40,000 - 1.2% 2 Agro-food Exports 2.4 Billion NIS - 3.7% Agro-food Import 5.3 Billion NIS - 7.3% Main constraints on Israeli Ag. sector Israel’s small land area is divided into 4 distinct climate zones Shortage of natural water resources Scarcity of precipitation Two thirds of Israel area is defined as semi- arid or arid Shortage of “On farm labor” Complex geopolitical environment Distance from the export & import markets Additional constraints Support of Agriculture in Israel Low level of support for farmers, Compared to other developed countries Decline of support levels over time Mainly, distortive market price support measures Research, Economy and Strategy Division - Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development Producer Support Estimates by Country (% of gross farm receipts) 2014 2013 % 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 -10 Source: OECD, PSE/CSE Database, 2015 Israeli Agriculture R&D and Investment (From OECD report on the Israeli Agriculture) The Agriculture sector has benefited from high levels of investment in research and development, well developed education systems and high performing extension serviced Israel is a world leader in many aspects of agricultural technology, particularly those associated with -

Prevalence of Asthma Among Young Men Residing in Urban Areas with Different Sources of Air Pollution Nili Greenberg Phd1,3, Rafael S

,0$-ǯ92/21ǯ'(&(0%(52019 ORIGINAL ARTICLES Prevalence of Asthma among Young Men Residing in Urban Areas with Different Sources of Air Pollution Nili Greenberg PhD1,3, Rafael S. Carel MD DrPH1, Jonathan Dubnov MD MPH1, Estela Derazne MSc3 and Boris A. Portnov PhD DSc2 1School of Public Health and 2Department of Natural Resources and Environment Management, University of Haifa, Israel 3Israeli Defense Forces, Medical Corps, Israel data used in different studies. Two studies by Greenberg and ABSTRACT: Background: Asthma is a common respiratory disease, which colleagues [6,7], which were based on individual data obtained is linked to air pollution. However, little is known about the for a large nation-wide cohort of young men, demonstrated effect of specific air pollution sources on asthma occurrence. higher prevalence rates of asthma in more polluted areas. Objective: To assess individual asthma risk in three urban The studies also showed a statistically significant association areas in Israel characterized by different primary sources of air between asthma risk and residential exposure to nitrogen diox- pollution: predominantly traffic-related air pollution (Tel Aviv) ide (NO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) air pollutants. However, or predominantly industrial air pollution (the Haifa bay area little is known about the effect of specific sources of air pollu- and Hadera). tion on asthma prevalence. Methods: The medical records of 13,875, 16- to 19-year-old males, who lived in the affected urban areas prior to their BACKGROUND STUDIES army recruitment and who underwent standard pre-military Air pollution from motor traffic and industries is significantly health examinations during 2012–2014, were examined. -

The Arab Bedouin Indigenous People of the Negev/Nagab

The Arab Bedouin indigenous people of the Negev/Nagab – A Short Background In 1948, on the eve of the establishment of the State of Israel, about 65,000 to 100,000 Arab Bedouin lived in the Negev/Naqab region, currently the southern part of Israel. Following the 1948 war, the state began an ongoing process of eviction of the Arab Bedouin from their dwellings. At the end of the '48 war, only 11,000 Arab Bedouin people remained in the Negev/Naqab, most of the community fled or was expelled to Jordan and Egypt, the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula. During the early 1950s and until 1966, the State of Israel concentrated the Arab Bedouin people in a under military administration. In this (سياج) ’closed zone known by the name ‘al-Siyāj period, entire villages were displaced from their locations in the western and northern Negev/Naqab and were transferred to the Siyāj area. Under the Planning and Construction Law, legislated in 1965, most of the lands in the Siyāj area were zoned as agricultural land whereby ensuring that any construction of housing would be deemed illegal, including all those houses already built which were subsequently labeled “illegal”. Thus, with a single sweeping political decision, the State of Israel transformed almost the entire Arab Bedouin collective into a population of whereas the Arab Bedouins’ only crime was exercising their basic ,״lawbreakers״ human right for adequate housing. In addition, the state of Israel denies any Arab Bedouin ownership over lands in the Negev/Naqab. It does not recognize the indigenous Arab Bedouin law or any other proof of Bedouin ownership over lands. -

A Pre-Feasibility Study on Water Conveyance Routes to the Dead

A PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER CONVEYANCE ROUTES TO THE DEAD SEA Published by Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, Kibbutz Ketura, D.N Hevel Eilot 88840, ISRAEL. Copyright by Willner Bros. Ltd. 2013. All rights reserved. Funded by: Willner Bros Ltd. Publisher: Arava Institute for Environmental Studies Research Team: Samuel E. Willner, Dr. Clive Lipchin, Shira Kronich, Tal Amiel, Nathan Hartshorne and Shae Selix www.arava.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW 5 2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF THE MED-DEAD SEA CONVEYANCE PROJECT ................................................................... 7 2.2 THE HISTORY OF THE CONVEYANCE SINCE ISRAELI INDEPENDENCE .................................................................. 9 2.3 UNITED NATIONS INTERVENTION ......................................................................................................... 12 2.4 MULTILATERAL COOPERATION ............................................................................................................ 12 3 MED-DEAD PROJECT BENEFITS 14 3.1 WATER MANAGEMENT IN ISRAEL, JORDAN AND THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY ............................................... 14 3.2 POWER GENERATION IN ISRAEL ........................................................................................................... 18 3.3 ENERGY SECTOR IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 20 3.4 POWER GENERATION IN JORDAN ........................................................................................................ -

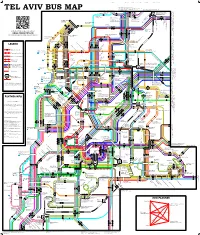

Tel Aviv Bus Map 2011-09-20 Copy

Campus Broshim Campus Alliance School Reading Brodetsky 25 126 90 501 7, 25, 274 to Ramat Aviv, Tel 274 Aviv University 126, 171 to Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv University, Ramat Aviv Gimel, Azorei Hen 90 to Hertzliya industrial zone, Hertzliya Marina, Arena Mall 24 to Tel Aviv University, Tel Barukh, Ramat HaSharon 26, 71, 126 to Ramat Aviv HaHadasha, Levinsky College 271 to Tel Aviv University 501 to Hertzliya, Ra’anana 7 171 TEL AVIV BUS MAP only) Kfar Saba, evenings (247 to Hertzliya, Ramat48 to HaSharon, Ra’anana Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul189 to Kiryat Atidim Yisgav, Barukh, Ramat HaHayal, Tel Aviv: Tel North-Eastern89 to Sde Dov Airport 126 Tel Aviv University & Shay Agnon/Levi Eshkol 71 25 26 125 24 Exhibition Center 7 Shay Agnon 171 289 189 271 Kokhav HaTzafon Kibbutzim College 48 · 247 Reading/Brodetsky/ Planetarium 89 Reading Terminal Eretz Israel Museum Levanon Rokah Railway Station University Park Yarkon Rokah Center & Convention Fair Namir/Levanon/Agnon Eretz Israel Museum Tel Aviv Port University Railway Station Yarkon Park Ibn Gvirol/Rokah Western Terminal Yarkon Park Sportek 55 56 Yarkon Park 11 189 · 289 9 47 · 247 4 · 104 · 204 Rabin Center 174 Rokah Scan this QR code to go to our website: Rokah/Namir Yarkon Park 72 · 172 · 129 Tennis courts 39 · 139 · 239 ISRAEL-TRANSPORT.COM 7 Yarkon Park 24 90 89 Yehuda HaMaccabi/Weizmann 126 501 The community guide to public transport in Israel Dizengo/BenYehuda Ironi Yud-Alef 25 · 125 HaYarkon/Yirmiyahu Tel Aviv Port 5 71 · 171 · 271 · 274 Tel Aviv Port 126 Hertzliya MosheRamat St, Sne HaSharon, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 524, 525, 531 to Kiryat (Ramat St HaHayal), Atidim Wallenberg Raoul Mall, Ayalon 142 to Kiryat Sharet, Neve Atidim St, HaNevi’a Dvora St, Rozen Pinhas Mall, Ayalon 42 to 25 · 125 Ben Yehuda/Yirmiyahu 24 Shikun Bavli Dekel Country Club Milano Sq. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case.