Complaint No 140/2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major International Tobacco Contraband Network Dismantled in Italy and Germany

PRESS RELEASE No 23 /2014 8 December 2014 Major international tobacco contraband network dismantled in Italy and Germany On 27 November 2014, law enforcement authorities in Italy (Agenzia delle Dogane and Guardia di Finanza) and Germany (Zollkriminalamt Köln and Zollfahndungsamt Berlin) succeeded in dismantling an international tobacco contraband network. The European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) contributed to the joint efforts that led to this successful operation. Under the coordination of the Prosecutors of Turin and Frankfurt/Oder, law enforcement officials searched a cigarette production plant near Turin which was found to be producing “made in Italy” cigarettes destined in part for the illegal market in the EU. Investigations are continuing, but to date over 10 persons have been arrested and a large amount of documents detailing financial transactions concerning this traffic were seized. The network produced cigarettes in the EU. It then simulated fictitious exports outside the EU or carried out real exports to third countries and subsequently smuggled the cigarettes back into the EU with the aim of avoiding the applicable customs duties and taxes. It is estimated that the harm caused to the Italian budget alone is in excess of €90 million. The final figures are likely to be much higher. OLAF had, since 2012, investigated activities linked to this network and cooperated in the criminal investigations organised jointly by the Italian and German authorities that led to this operation. In this context, OLAF organised a coordination meeting in autumn 2013 with judicial and law enforcement authorities of these countries and cooperated with several other EU Member States (Belgium, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia) and third countries (Moldavia, Ukraine). -

Activity-Report-2004

2004 Annual Report 1 © SECI Regional Center for Combating Transborder Crime Reproduction is authorized provided that the source is acknowledged. Printed in Bucharest, Romania April, 2005 2 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ATTF Anti-Terrorism Task Force DEA Drug Enforcement Administration EU European Union EC European Commission DHS Department of Homeland Security FBI Federal Bureau of Investigation GUUAM Georgia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, Moldova ICMPD International Center for Migration Policy and Development IOM International Organization for Migration CEI Central European Initiative JCC Joint Cooperation Committee NFP National Focal Point NGO Non Governmental Organization MOU Memorandum of Understanding OSCE Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe OSD Operational Support Department RACVIAC Regional Arms Control and Verification Information and Assistance Center SALW Small Arms and Light Weapons SECI Southeast European Cooperative Initiative SECI Center Regional Center for Combating Transborder Crime SEE South East Europe SEEPAG South East European Prosecutors Advisory Group SEESAC South Eastern Europe Clearinghouse for the Control of Small Arms and Light Weapons SPOC Stability Pact Initiative against Organized Crime TF Task Force THB Trafficking in Human Beings USSS United States Secret Service WCO World Customs Organization WMD Weapons of Mass Destruction ZKA German Customs Investigation Office (Zollkriminalamt) 3 1 Forewords 1.1. JCC Chairman, Dr. Ferenc Banfi The SECI Regional Centre for Combating Transborder Crime, with the support of the 12 Member Countries, the two Permanent Advisors (Interpol and World Customs Organisation), together with the Observer Countries and organisations, has achieved in quite a short time considerable success in tackling organized crime in the region. The future development of the SECI Centre, outlined in our Strategy for the period 2005-2010, describes a flexible and effective regional law enforcement tool, capable of assuming a leading role in South-Eastern European response to cross-border crime. -

An Integrated Civil Police Force for the European Union

AN INTEGRATED CIVIL POLICE FORCE FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION TASKS, PROFILE AND DOCTRINE CARLO JEAN CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY STUDIES BRUSSELS The Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) is an independent policy research institute in Brussels. Its mission is to produce sound analytical research leading to constructive solutions to the challenges facing Europe today. As a research institute, CEPS takes no position on matters of policy. The views expressed are entirely those of the author. Carlo Jean is currently Professor of Strategic Studies at LUISS (Libera Università Internazionale di Studi Sociali) in Rome. He is a retired Lieutenant General of the Italian Army, former Military Advisor to the Italian President of the Republic and Commander of the Centre of High Defence Studies, Rome. He served as Personal Representative of the OSCE Chairman in Office for the implementation of parts of the Dayton- Paris Peace Accords. Professor Jean has published extensively on security and military issues, geopolitics and geo-economics. The author would like to express his gratitude to Brigadier General Vincent Coeurderoy of the French Gendarmerie, IPTF Commissioner in the UNMIBiH, and to Colonel Vincenzo Coppola of the Italian Carabinieri and former Commander of the SFOR-MSU for their advice and support. ISBN 92-9079- 379-1 © Copyright 2002, Centre for European Policy Studies. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the Centre for European Policy Studies. Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1, B-1000 Brussels Tel: 32 (0) 2 229.39.11 Fax: 32 (0) 2 219.41.51 e-mail: [email protected] internet: http://www.ceps.be CONTENTS Executive Summary ..........................................................................................................1 1. -

7644/1/05 REV 1 DCL 1 VG DG F 2A Delegations Will

Council of the European Union Brussels, 13 January 2016 (OR. en) 7644/1/05 REV 1 DCL 1 CRIMORG 31 DECLASSIFICATION of document: ST 7644/1/05 REV 1 RESTREINT UE dated: 2 May 2005 new status: Public Subject: EVALUATIONREPORT THIRD ROUND OF MUTUAL EVALUATIONS "EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION AND INTELLIGENCE BETWEEN EUROPOL AND THE MEMBER STATES AND BETWEEN THE MEMBER STATES RESPECTIVELY" REPORT ON ITALY Delegations will find attached the declassified version of the above document. The text of this document is identical to the previous version. 7644/1/05 REV 1 DCL 1 VG DG F 2A EN RESTREINT UE COUNCIL OF Brussels, 2 May 2005 THE EUROPEAN UNION 7644/1/05 REV 1 RESTREINT UE CRIMORG 31 EVALUATION REPORT ON THE THIRD ROUND OF MUTUAL EVALUATIONS "EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION AND INTELLIGENCE BETWEEN EUROPOL AND THE MEMBER STATES AND BETWEEN THE MEMBER STATES RESPECTIVELY" REPORT ON ITALY 7644/1/05 REV 1 EL/ld 1 DG H III RESTREINT UE EN RESTREINT UE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 3 2. GENERAL INFORMATION AND STRUCTURES ................................................................... 4 3. INTERNAL ORGANISATION OF THE EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION ........................ 38 4. EXTERNAL EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION ..................................................................... 40 5. EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION BETWEEN MEMBER STATES AND EUROPOL ......... 41 6. EVALUATION BY EXPERT TEAM ........................................................................................ -

Orientamento Alle Carriere in Divisa

con il sostegno di ORIENTAMENTO ALLE CARRIERE IN DIVISA Alcuni sognano il successo, altri si attivano per raggiungerlo Un lavoro stabile e duraturo Scopri le opportunità fornite dalle FORZE ARMATE e dalle Una brillante carriera FORZE DI POLIZIA in divisa per indossare la divisa Una laurea triennale e/o magistrale FORZE ARMATE FORZE DI POLIZIA Si occupano prevalentemente della difesa del territorio Intervengono per tutelare l’ordine e la sicurezza pubblica e intervengono in casi di calamità naturali Esercito Marina Aeronautica Arma dei Carabinieri* Guardia di Polizia Polizia Italiano Militare Militare (Corpo Forestale dal Finanza di Stato Penitenziaria 2016 inglobato nei CC) CORPI MILITARI CORPI CIVILI * L’Arma dei Carabinieri, oltre a rappresentare un Corpo di Polizia, è la quarta Forza Armata, con compiti di Polizia Militare FORZE ARMATE FORZE DI POLIZIA Per entrare a far parte delle Forze Armate e delle UFFICIALI DIRETTORI/FUNZIONARI Forze di Polizia è necessario partecipare a dei Concorsi pubblici (aperti a tutti i cittadini italiani di entrambi i sessi in possesso di determinati MARESCIALLI/ISPETTORI ISPETTORI requisiti), oppure a dei Concorsi interni (riservati al personale delle Amministrazioni in divisa – utili VOLONTARI/AGENTI AGENTI per la carriera interna). Piramide dei Ruoli del personale Scansiona con il tuo telefono questo QrCode e scarica le guide gratuite ai concorsi CORPI CONCORSI UFFICIALI MILITARI FORMAZIONE LAUREA GRADO STIPENDIO 5 anni Magistrale Tenente Mensile (da subito) Accademie Militari Esercito, Marina, Aeronautica -

Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 5 January 2009

United Nations E/CN.7/2009/7 Economic and Social Council Distr.: General 5 January 2009 Original: English Commission on Narcotic Drugs Fifty-second session Vienna, 11-20 March 2008 Item 6 (a) of the provisional agenda* Illicit drug traffic and supply: world situation with regard to drug trafficking and action taken by subsidiary bodies of the Commission Provision of international assistance to the most affected States neighbouring Afghanistan Report of the Executive Director Summary Data collected in Afghanistan: Opium Poppy Survey 2008, Executive Summary, a publication prepared by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the Ministry of Counter Narcotics of Afghanistan, show that 159,000 hectares of land were under opium poppy cultivation in 2008, a decrease of 19 per cent compared with 2007. In 2008, however, favourable weather conditions resulted in the highest opium yields ever (48.8 kg per hectare) compared with the already high yield recorded in 2007 (42.5 kg per hectare). Afghanistan produced an extraordinary 7,700 tons of opium in 2008 (6 per cent less than in 2007), thereby remaining the largest supplier of opiates in the world (accounting for over 90 per cent of global production). Afghanistan’s neighbouring States are affected by trafficking in opium, morphine and refined heroin, as well as by the diversion and smuggling of precursor chemicals, the operation of clandestine laboratories illicitly manufacturing drugs and the abuse of and addiction to opiates. In order to seek solutions to the drug problem, affected States are coming together through the Rainbow Strategy, which is based on the principle of shared responsibility. -

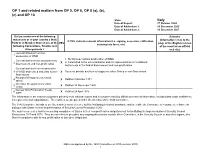

Italy OP 1 and Related Matters from OP 5, OP 6, OP 8 (A), (B), (C) And

OP 1 and related matters from OP 5, OP 6, OP 8 (a), (b), (c) and OP 10 State: Italy Date of Report: 27 October 2004 Date of Addendum 1: 05 December 2005 Date of Addebdum 2: 10 December 2007 Did you make one of the following Remarks statements or is your country a State (information refers to the if YES, indicate relevant information (i.e. signing, accession, ratification, Party to or Member State of one of the YES page of the English version entering into force, etc) following Conventions, Treaties and of the report or an official Arrangements ? web site) General statement on non- 1 possession of WMD 1. EU Strategy against proliferation of WMD General statement on commitment to 2 X 2. Committed to the universalization and full implementation of multilateral disarmament and non-proliferation instruments in the field of disarmament and non-proliferation General statement on non-provision 3 of WMD and related materials to non- X Does not provide any form of support to either States or non-State actors State actors Biological Weapons Convention 4 X Ratified 8 October 1974 (BWC) Chemical Weapons Convention 5 X Ratified 18 November 1995 (CWC) Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty 6 X Ratified 24 April 1975 (NPT) The information in the matrices originates primarily from national reports and is complemented by official government information, including that made available to inter-governmental organizations. The matrices are prepared under the direction of the 1540 Committee. The 1540 Committee intends to use the matrices as a reference tool for facilitating technical assistance and to enable the Committee to continue to enhance its dialogue with States on their implementation of Security Council Resolution 1540. -

Afghanistan's Police

UNITeD StateS INSTITUTe of Peace www.usip.org SPeCIAL RePoRT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Robert M. Perito The Afghanistan National Police is Afghanistan’s front line of defense against insurgency and organized crime. Yet despite nearly $10 billion in international police assistance, the Afghan police are riddled with corruption and incompetence and are far from the professional law enforcement organization needed Afghanistan’s Police to ensure stability and development. This report details the past failures and current challenges facing the international police assistance program in Afghanistan. It draws conclusions about the prospects for current programs and offers The Weak Link in Security Sector Reform recommendations for corrective action. The report urges that the international community’s approach to police assistance expand to embrace a comprehensive program for security Summary sector reform and the rule of law. • In seven years, the Afghan National Police forces have grown to 68,000 personnel, with The report is based on a conference titled “Policing a target end strength of 86,000. The ANP includes the uniformed police force, which is Afghanistan,” which was hosted by the United States Institute responsible for general police duties, and specialized police forces, which deal with public of Peace’s Security Sector Reform Working Group on May 27, order, counternarcotics, terrorism, and border control. 2009. It draws on the author’s participation in numerous Afghanistan-related conferences, interviews, workshops, and • Despite the impressive growth in numbers, the expenditure of $10 billion in international study groups; on his two visits to the country; and on an police assistance, and the involvement of the United States, the European Union, and extensive review of the literature on the Afghanistan police multiple donors, the ANP is riddled with corruption and generally unable to protect Afghan development program. -

Report to the Italian Government on the Visit to Italy Carried out by The

CPT/Inf (2010) 14 Report to the Italian Government on the visit to Italy carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT) from 27 to 31 July 2009 The Italian Government has requested the publication of this report and of its response. The Government’s response is set out in document CPT/Inf (2010) 15. Strasbourg, 28 April 2010 - 2 - CONTENTS Copy of the letter transmitting the CPT’s report............................................................................3 I. INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................4 A. Dates of the visit and composition of the delegation ..............................................................4 B. Purpose of the visit....................................................................................................................4 C. Consultations held by the delegation.......................................................................................5 D. Establishments visited...............................................................................................................5 E. Co-operation received...............................................................................................................6 II. FACTS FOUND DURING THE VISIT AND ACTION PROPOSED ................................7 A. The push-back operations ........................................................................................................7 -

Using the Italian Crisis to Impose Control: a Shift Towards a Fiscal Surveillance State?

Analysis Using the Italian crisis to impose control: a shift towards a fiscal surveillance state? Yasha Maccanico The “technical” government has introduced passports for small children, limits on cash transactions, compulsory bank accounts and the “redditometro” (income-meter) to counter tax evasion. After taking over from Silvio Berlusconi’s discredited government on 16 November 2011, the “technical” executive led by Mario Monti tackled a number of structural problems with the Italian economy such as widespread tax evasion and a sizeable underground economy. Measures approved during Monti’s 14 months at the helm included: limits on the use of cash; targeted controls by the customs and excise police (Guardia di Finanza, GdF) in exclusive holiday resorts; the introduction of passports for infants and forcing everyone to have bank accounts. A personal bank account - set up by their parents - will be necessary for children to pay for their passports and for pensioners to receive pension payments above 500 euros. Increased control has been coupled with “austerity” measures which range from cuts to public services, eligibility for pensions being delayed, an assault on workers’ rights that undermines the security of employment and a spending review to rein in costs that are viewed as wasteful. The “technical” government fell on 21 December 2012 when Monti resigned after opposition from Berlusconi’s Popolo della Libertà (PdL) caused him to lose his majority in parliament. After elections were called for February 2013, Monti threw off his mantle of impartiality (to maintain which he had been granted the status of senator for life by president Giorgio Napolitano) by standing for election when it became apparent that the Partito Democratico (PD) would run in alliance with Sinistra, Ecologia e Libertà (SEL, Left, Environment and Freedom). -

Comparative Analysis of the Reports Supplied by the Member States on National Measures Taken to Combat Wastefulness and the Misuse of Community Resources

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 14.11.1995 COM(95) 556 final PROTECTION OF THE COMMUNITY'S FINANCIAL INTERESTS SYNTHESIS DOCUMENT of the comparative analysis of the reports supplied by the Member States on national measures taken to combat wastefulness and the misuse of Community resources II COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS II of the reports supplied by the Member States (presented by the Coa-ission> COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 08. 12. 1995 CORRIGENDUM COM(95) 556 final /2 Nouvelles pages :A4, AS et 9. Annulent et remplacent celles du COM(95)556 final du 14.11.1995 CONCBRNB UNIQUEMBNT LES VERSIONS FR . e t B n. PROTECTION OF THE COMMUNITY'S FINANCIAL INTERESTS SYNTHESIS DOCUMENT of the comparative analysis of the reports supplied by the Member States on national measures taken to combat wastefulness and the misuse of Community resources COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS of the reports supplied by the Member States (presented by the C~ission> PROTECTION OF THE COMMUNITY'S FINANCIAL INTERESTS SYNTHESIS DOCUMENT of the comparative analysis of the reports supplied by the Member States on national measures taken to combat ·wastefulness and the misuse of Community resources The remit On 11 July 1994 the Council (Ecofin) asked the Commission to 'produ~e a progress report no later than the end of 1995 on the application of Article 209a of the EC Treaty' which enshrines the 'principle of assimilation' and aims to strengthen 'the principle of co-operation'. Subsequently, the Essen European Council on 9 and 10 December 1994 called on the Member States to ·submit reports on the measures they are implementing to combat wastefulness and the misuse of Community resources', to be examined by the Council (Ecofin) in June 1995 and submitted to the European Council in December 1995. -

The Paradox of Gendarmeries: Between Expansion, Demilitarization and Dissolution

0088 CCOUVERTUREOUVERTURE pp1X.ai1X.ai 1 229-10-139-10-13 33:49:51:49:51 PPMM SSR PAPER 8 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K The Paradox of Gendarmeries: Between Expansion, Demilitarization and Dissolution Derek Lutterbeck DCAF DCAF a centre for security, development and the rule of law SSR PAPER 8 The Paradox of Gendarmeries: Between Expansion, Demilitarization and Dissolution Derek Lutterbeck DCAF The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF) is an international foundation whose mission is to assist the international community in pursuing good governance and reform of the security sector. The Centre develops and promotes norms and standards, conducts tailored policy research, identifies good practices and recommendations to promote democratic security sector governance, and provides in‐country advisory support and practical assistance programmes. SSR Papers is a flagship DCAF publication series intended to contribute innovative thinking on important themes and approaches relating to security sector reform (SSR) in the broader context of security sector governance (SSG). Papers provide original and provocative analysis on topics that are directly linked to the challenges of a governance‐driven security sector reform agenda. SSR Papers are intended for researchers, policy‐makers and practitioners involved in this field. ISBN 978‐92‐9222‐286‐4 © 2013 The Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces EDITORS Heiner Hänggi & Albrecht Schnabel PRODUCTION Yury Korobovsky COPY EDITOR Cherry Ekins COVER IMAGES © ‘Gendarmerie Line’ by Mike Baker, ‘French Gendarmerie being trained by Belgian Soldiers in IEDs in Afghanistan’ by unidentified government source, ‘Guardia Civil’ by Joaquim Pol, ‘Carabinieri’ by hhchalle The views expressed are those of the author(s) alone and do not in any way reflect the views of the institutions referred to or represented within this paper.