Pretext Pages of Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

September 16-30, 1971

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 9/18/1971 A Appendix “A” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 9/19/1971 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 9/23/1971 A Appendix “A” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 9/25/1971 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 9/26/1971 A Appendix “B” 6 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 9/27/1971 A Appendix “B” 7 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 9/30/1971 A Appendix “E” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-8 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary September 16, 1971 – September 30, 1971 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

State News 19611109.Pdf

wSmÊëmI ■ I W ^ Ê tw m m M í^K'rÁíSl?’' mm ÉlilliP m * V inÉP w :mE HimPinyfifl gflPïîjfi S a Bêi*mû ClâM PMUft f i l i l i Statt Landa*, MlPh 8 P a g e s 5 C en ia Eatablfobed 1909 VoL 53, No. 9 7 e m e n o n Swainson JFK Conference: BULLETIN Fear Civil RICHMOND, V a . (Ft—A Southbound Imperial AirUnes Liberties Addresses Move for Defense plane wife 82 persons nfaoard 78 Army recruits snd s crew te WASHINGTON UB-President At Ms harne at Gettysburg, five—crushed in a ravine and Affected Farmers Kennedy said Wednesday tbat Pa., Eiseahawer voiced gnti- horned jute south te Richmond ' ’ _ y . : “We are going to ask for ad ficatioa at fee aaaaacenroat Wednesday night Police said By MARY BASING Governor John B. Swainson ditional funds tot defense next aad stei he wenhl he delight apparently only two persons Of fee Style News Staff wig kick off the Thursday ses y e a r/' even though he considers ed if be can further the pro survived. sion te tbe 42nd annual meeting the United States second to no gram. Should tiro . University be in te tbe Michigan Farm Bureau other country in military pow Russia has fired into the air Ronald Conway, TO, te West the business of criminal in here at 9 a.m. in fee Andjfcnv er.- ; É pl¡i|¡ about 170 megatons of nuclear Hollywood, Fla-, raptaia te vestigation? ium. He will give tbe call to Quoting himself, Kennedy devices—the equivalent of 170 the aircraft aad one te tiro “The time is overdue for ader and an address to the said that on the basis te pres million tons te TNT—while the survivors, said tbe men aboard faculty to take a long, cote look some 2,090 members. -

Montana Kaimin, April 28, 2010 Students of the Niu Versity of Montana, Missoula

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 4-28-2010 Montana Kaimin, April 28, 2010 Students of The niU versity of Montana, Missoula Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Students of The nivU ersity of Montana, Missoula, "Montana Kaimin, April 28, 2010" (2010). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 5323. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/5323 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Page 5 Pages 7-11 Page 13 Foresters gather ASUM candidates Recalling the for a day answer questions Mount St. Helens of competition before election eruption after 30 years www.montanakaimin.com MKontana UM’s Independent Campus Newspaper Since 1898 aVolumeimin CXII Issue 96 Wednesday, April 28, 2010 Endangered species of the mind The past and future of the President’s Lecture Series Andrew Dusek position he thoroughly enjoys, Montana Kaimin and he completely invests himself With the carefully constructed in the coordination process, from cadences of an academic, Alexan- establishing initial contact to the der Nehamas spoke to the crowd lecturer’s last uttered phrase. that had gathered in the dark- The process begins more than ness before him on a late-March a year in advance. -

KPBS September TV Lisitings

SEPTEMBER Programming Schedule Listings are as accurate as possible at press time but are subject to change due to updated programming. For complete up-to-date listings, including overnight programs, visit kpbs.org/tv, or call (619) 594-6983. KPBS Schedule At-A-Glance MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 AM CLASSICAL STRETCH 5:30 AM YOGA Visit Visit www.kpbs.org/tv www.kpbs.org/tv 6:00 AM PEG + CAT for schedule information for schedule information 6:30 AM ARTHUR 7:00 AM READY JET GO! SESAME STREET SESAME STREET DANIEL TIGER'S DANIEL TIGER'S 7:30 AM NATURE CAT NEIGHBORHOOD NEIGHBORHOOD PINKALICIOUS & PINKALICIOUS & 8:00 AM WILD KRATTS PETERRIFIC PETERRIFIC 8:30 AM MOLLY OF DENALI CURIOUS GEORGE CURIOUS GEORGE 9:00 AM CURIOUS GEORGE LET’S GO LUNA LETS GO LUNA 9:30 AM LET’S GO LUNA NATURE CAT NATURE CAT 10:00 AM DANIEL TIGER WASHINGTON WEEK 10:30 AM DANIEL TIGER Visit KPBS ROUNDTABLE www.kpbs.org/tv 11:00 AM SESAME STREET for schedule information A GROWING PASSION GROWING A 11:30 AM PINKALICIOUS & PETTERIFIC GREENER WORLD 12:00 PM DINOSAUR TRAIN THIS OLD HOUSE 12:30 PM CAT IN THE HAT KNOWS ABOUT THAT! ASK THIS OLD HOUSE NEW SCANDINAVIAN 1:00 PM SESAME STREET COOKING 1:30 PM SPLASH AND BUBBLES JAMIE’S FOOD Visit www.kpbs.org/tv 2:00 PM PINKALICIOUS & PETERRIFIC AMERICA’S TEST KITCHEN for schedule information 2:30 PM LET’S GO LUNA! MARTHA STEWART MEXICO ONE PLATE 3:00 PM NATURE CAT AT A TIME 3:30 PM WILD KRATTS CROSSING SOUTH KEN KRAMER’S 4:00 PM MOLLY OF DENALI RICK STEVES EUROPE ABOUT SAN DIEGO HISTORIC PLACES 4:30 PM ODD SQUAD KPBS/ARTS WITH ELSA SEVILLA PBS NEWSHOUR PBS NEWSHOUR 5:00 PM KPBS EVENING EDITION WEEKEND WEEKEND FIRING LINE WITH 5:30 PM NIGHTLY BUSINESS REPORT KPBS ROUNDTABLE MARGARET HOOVER 6:00 PM BBC WORLD NEWS Visit 6:30 PM KPBS EVENING EDITION LAWRENCE WELK www.KPBS.org/TV for schedule information 7:00 PM PBS NEWSHOUR KPBS-TV Programming Schedule – SEPTEMBER 2019 1 Sunday, September 1 11:00 KPBS Retire Safe & Secure with Ed Slott 2019 America needs Ed Slott now 6:00PM PBS Previews: Country Music KPBS more than ever. -

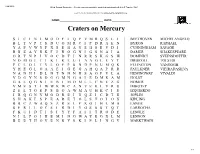

2D Mercury Crater Wordsearch V2

3/24/2019 Word Search Generator :: Create your own printable word find worksheets @ A to Z Teacher Stuff MAKE YOUR OWN WORKSHEETS ONLINE @ WWW.ATOZTEACHERSTUFF.COM NAME:_______________________________ DATE:_____________ Craters on Mercury SICINIMODFIQPVMRQSLJ BEETHOVEN MICHELANGELO BLTVPTSDUOMRCIPDRAEN BYRON RAPHAEL YAPVWYPXSEHAUEHSEVDI CUNNINGHAM SAVAGE RRZAYRKFJROGNIGSNAIA DAMER SHAKESPEARE ORTNPIVOCDTJNRRSKGSW DOMINICI SVEINSDOTTIR NOMGETIKLKEUIAAGLEYT DRISCOLL TOLSTOI PCLOLTVLOEPSNDPNUMQK ELLINGTON VANGOGH YHEGLOAAEIGEGAHQAPRR FAULKNER VIEIRADASILVA NANHIDLNTNNNHSAOFVLA HEMINGWAY VIVALDI VDGYNSDGGMNGAIEDMRAM HOLST GALQGNIEBIMOMLLCNEZG HOMER VMESTIWWKWCANVEKLVRU IMHOTEP ZELTOEPSBOAWMAUHKCIS IZQUIERDO JRQGNVMODREIUQZICDTH JOPLIN SHAKESPEARETOLSTOIOX KIPLING BBCZWAQSZRSLPKOJHLMA LANGE SFRLLOCSIRDIYGSSSTQT LARROCHA FKUIDTISIYYFAIITRODE LENGLE NILPOJHEMINGWAYEGXLM LENNON BEETHOVENRYSKIPLINGV MARKTWAIN 1/2 Mercury Craters: Famous Writers, Artists, and Composers: Location and Sizes Beethoven: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770−1827). German composer and pianist. 20.9°S, 124.2°W; Diameter = 630 km. Byron: Lord Byron (George Byron) (1788−1824). British poet and politician. 8.4°S, 33°W; Diameter = 106.6 km. Cunningham: Imogen Cunningham (1883−1976). American photographer. 30.4°N, 157.1°E; Diameter = 37 km. Damer: Anne Seymour Damer (1748−1828). English sculptor. 36.4°N, 115.8°W; Diameter = 60 km. Dominici: Maria de Dominici (1645−1703). Maltese painter, sculptor, and Carmelite nun. 1.3°N, 36.5°W; Diameter = 20 km. Driscoll: Clara Driscoll (1861−1944). American glass designer. 30.6°N, 33.6°W; Diameter = 30 km. Ellington: Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899−1974). American composer, pianist, and jazz orchestra leader. 12.9°S, 26.1°E; Diameter = 216 km. Faulkner: William Faulkner (1897−1962). American writer and Nobel Prize laureate. 8.1°N, 77.0°E; Diameter = 168 km. Hemingway: Ernest Hemingway (1899−1961). American journalist, novelist, and short-story writer. 17.4°N, 3.1°W; Diameter = 126 km. -

The George-Anne Student Media

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern The George-Anne Student Media 4-2-2009 The George-Anne Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Georgia Southern University, "The George-Anne" (2009). The George-Anne. 3158. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/george-anne/3158 This newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Media at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George-Anne by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■■I^^^BMI Serving Georgia Southern University and the Statesboro Community Since 1927 • Questions? Call 912-478-5246. f 1 ^ ^ www.GADaily.com LrEORGE- THURSDAY, APRIL 2,2009 • VOLUME 82. • ISSUE 1 COVERING THE CAMPUS LIKE A SWARM OF GNATS Special Photo NEWS > ' Three-Day Forecast . Web Exclusive: 'Battle for the Boro' gears up for Today Saturday the weekend at Dos Primos and I Friday T-storms "•**%*"<*' T-storms Living with Celiac Disease Shenanigans. See if your favorite T-storms 70/61 0 77/47 79/52 Only at www.GADaily.com Vband is on the list. PAGE 13; V*fc jm PAGE 2 I ADVERTISEMENT THE GEORGE-ANNE I THURSDAY, APRIL 2,2009 VQtl /OHwireless 1 ^■BI^L Unlimited calling to any 10 numbers. Anywhere in America. Anytime, /lumbers to share on any Nationwide Family SharePlan® with 1400 Anytime Minutes or more. ers on any Nationwide Single-Line Plan with 900 Anytime Minutes or more. -

Institute for Astronomy University of Hawai'i at M¯Anoa Publications in Calendar Year 2013

Institute for Astronomy University of Hawai‘i at Manoa¯ Publications in Calendar Year 2013 Aberasturi, M., Burgasser, A. J., Mora, A., Reid, I. N., Barnes, J. E., & Privon, G. C. Experiments with IDEN- Looper, D., Solano, E., & Mart´ın, E. L. Hubble Space TIKIT. In ASP Conf. Ser. 477: Galaxy Mergers in an Telescope WFC3 Observations of L and T dwarfs. Evolving Universe, 89–96 (2013) Mem. Soc. Astron. Italiana, 84, 939 (2013) Batalha, N. M., et al., including Howard, A. W. Planetary Albrecht, S., Winn, J. N., Marcy, G. W., Howard, A. W., Candidates Observed by Kepler. III. Analysis of the First Isaacson, H., & Johnson, J. A. Low Stellar Obliquities in 16 Months of Data. ApJS, 204, 24 (2013) Compact Multiplanet Systems. ApJ, 771, 11 (2013) Bauer, J. M., et al., including Meech, K. J. Centaurs and Scat- Al-Haddad, N., et al., including Roussev, I. I. Magnetic Field tered Disk Objects in the Thermal Infrared: Analysis of Configuration Models and Reconstruction Methods for WISE/NEOWISE Observations. ApJ, 773, 22 (2013) Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejections. Sol. Phys., 284, Baugh, P., King, J. R., Deliyannis, C. P., & Boesgaard, A. M. 129–149 (2013) A Spectroscopic Analysis of the Eclipsing Short-Period Aller, K. M., Kraus, A. L., & Liu, M. C. A Pan-STARRS + Binary V505 Persei and the Origin of the Lithium Dip. UKIDSS Search for Young, Wide Planetary-Mass Com- PASP, 125, 753–758 (2013) panions in Upper Sco. Mem. Soc. Astron. Italiana, 84, Beaumont, C. N., Offner, S. S. R., Shetty, R., Glover, 1038–1040 (2013) S. C. -

2015 Spring Commencement Metropolitan State University of Denver

2015 SPRING COMMENCEMENT METROPOLITAN STATE UNIVERSITY OF DENVER SATURDAY, MAY 16, 2015 SPRING COMMENCEMENT SATURDAY, MAY 16, 2015 Letter from the President .......................... 2 MSU Denver: Transforming Lives, Communities and Higher Education .... 3 Marshals, Commencement Planning Committee, Retirees ............ 4 In Memoriam, Board of Trustees ............. 5 Academic Regalia ....................................... 6 Academic Colors ......................................... 7 Provost’s Award Recipient ......................... 8 Morning Ceremony Program .................... 9 President’s Award Recipient ................... 10 Afternoon Ceremony Program ................ 11 Morning Ceremony Candidates School of Education and College of Letters, Arts and Sciences ........................................ 12 Afternoon Ceremony Candidates College of Business and College of Professional Studies ..........20 Seating Diagrams ................................….27 1 DEAR 2015 SPRING GRADUATION CANDIDATES: Congratulations to you, our newest graduates! And welcome to your families and friends who have anticipated this day — this triumph — with immense pride. Each of our more than 80,000 graduates is unique, but all have one thing in common: Their lives were transformed by the education they received at MSU Denver. Most have stayed in Colorado, where they teach our children, own small businesses, create beautiful works of art, counsel families in crisis and design cutting-edge products that improve our lives. They are role models who have infused our state and their neighborhoods with economic growth, civic responsibility and culture. They have seized the opportunity to transform their families and their communities. Now it is your time to begin making the most of all that you have learned! MSU Denver transformed higher education in Colorado when, 50 years ago in the fall of 1965, we opened our doors with six majors, 1,187 students and a mission to give the opportunity to earn a college degree to almost anyone willing to take on the challenge. -

The Sacramento/San Joaquin Literary Watershed": Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

"The Sacramento/San Joaquin Literary Watershed": Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Publications of Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys and Sierra Nevada. Second Edition. Revised and Expanded. John Sherlock University of California, Davis 2010 1 "The Sacramento/San Joaquin Literary Watershed": Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys and Sierra Nevada TABLE OF CONTENTS. PUBLICATIONS OF REGIONAL SMALL PRESSES. Arranged Geographically by Place Of Publication. A. SACRAMENTO VALLEY SMALL PRESSES. 3 - 75 B. SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY SMALL PRESSES. 76 - 100 C. SIERRA NEVADA SMALL PRESSES. 101 - 127 D. SHASTA REGION SMALL PRESSES. 128 - 131 E. LITERARY MAGAZINES - CENTRAL VALLEY 132 - 145 F. LITERARY MAGAZINES - SIERRA NEVADA. 146 - 148 G. LOCAL AND REGIONAL ANTHOLOGIES. 149 - 155 PUBLICATIONS OF REGIONAL AUTHORS. Arranged Alphabetically by Author. REGIONAL AUTHORS. 156 - 253 APPENDIXES I. FICTION SET IN THE CENTRAL VALLEY. 254 - 262 II. FICTION SET IN THE SIERRA NEVADA. 263 - 272 III. SELECTED REGIONAL ANTHOLOGIES. 273 - 278 2 Part I. SACRAMENTO VALLEY SMALL LITERARY PRESSES. ANDERSON. DAVIS BUSINESS SERVICES (Anderson). BLACK, Donald J. In the Silence. [poetry] 1989 MORRIS PUB. (Anderson). ALDRICH, Linda. The Second Coming of Santa Claus and other stories. 2005 RIVER BEND BOOKS (Anderson, 1998). MADGIC, Bob. Pursuing Wilds Trout: a journey in wilderness values. 1998 SPRUCE CIRCLE PRESS (Anderson, 2002-present?). PECK, Barbara. Blue Mansion & Other Pieces of Time. 2002 PECK, Barbara. Vanishig Future: Forgotten Past. 2003 PECK, Barbara. Hot Shadows.: whispers from the vanished. -

Taylor University Catalog 1913

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University Undergraduate Catalogs Taylor University Catalogs 1913 Taylor University Catalog 1913 Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/catalogs Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Taylor University, "Taylor University Catalog 1913" (1913). Undergraduate Catalogs. 90. https://pillars.taylor.edu/catalogs/90 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Taylor University Catalogs at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Catalogs by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T a y I o r U nI v e r s i ty BULLETIN UPLAND, INDIANA 19 13 ^.v^Siw .,;> ., ,^ University x1 378 -JZlb c.Z 19/5 H. MARIA WRIGHT HALL HELENA MEMORIAL MUSIC HALL VOL. 5 MAY, 1913 No. 1 Taylor University BULLETIN TERMS OPEN September 24, 1913 January 2, 1914 Marcli 25, 1914 2 3. CATALOG NUIVIBER 1913^-1914^ MAY, 1913 UPLAND, INDIANA Entered a* Second-Classs Matter at Upland, Indiana, April 8th, 1909, under Act off Congress off July 16, 1894 iayior University Upland, Indian. CALENDAR FOR 1913 JULY AUOUST SEPTEMBER S M T W T F S 5 M T W T F S S M T W T F S 12 3 4 5 1 2 12 3 4 5 6 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 31 OCTOBER NOVEMBiER BEOBMBER 12 3 4 1 12 3 4 5 -

Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 102 Journals 109

Lorenzo Vitturi, from Money Must Be Made, published by SPBH Editions. See page 125. Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 102 Journals 109 CATALOG EDITOR Thomas Evans Fall Highlights 110 DESIGNER Photography 112 Martha Ormiston Art 134 IMAGE PRODUCTION Hayden Anderson Architecture 166 COPY WRITING Design 176 Janine DeFeo, Thomas Evans, Megan Ashley DiNoia PRINTING Sonic Media Solutions, Inc. Specialty Books 180 Art 182 FRONT COVER IMAGE Group Exhibitions 196 Fritz Lang, Woman in the Moon (film still), 1929. From The Moon, Photography 200 published by Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. See Page 5. BACK COVER IMAGE From Voyagers, published by The Ice Plant. See page 26. Backlist Highlights 206 Index 215 Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future Edited with text by Tracey Bashkoff. Text by Tessel M. Bauduin, Daniel Birnbaum, Briony Fer, Vivien Greene, David Max Horowitz, Andrea Kollnitz, Helen Molesworth, Julia Voss. When Swedish artist Hilma af Klint died in 1944 at the age of 81, she left behind more than 1,000 paintings and works on paper that she had kept largely private during her lifetime. Believing the world was not yet ready for her art, she stipulated that it should remain unseen for another 20 years. But only in recent decades has the public had a chance to reckon with af Klint’s radically abstract painting practice—one which predates the work of Vasily Kandinsky and other artists widely considered trailblazers of modernist abstraction. Her boldly colorful works, many of them large-scale, reflect an ambitious, spiritually informed attempt to chart an invisible, totalizing world order through a synthesis of natural and geometric forms, textual elements and esoteric symbolism. -

Index to Geophysical Abstracts 188-191 1962

Index to Geophysical Abstracts 188-191 1962 By JAMES W. CLARKE, DOROTHY B. VITALIANO, VIRGINIA S. NEUSCHEL, and others GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN '1166-E Abstracts of current literature pertaining to the physics of the solid earth and to geophysical exploration UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1963 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D.C. Price 40 cents (single copy). Subscription price: $0.00 a year; 00 cents additional for foreign mailing. Use of funds for printing this publication has been approved by the Director of the Bureau of the Budget. INDEX TO GEOPHYSICAL ABSTRACTS 188-191, 1962 By James W. Clarke and others AUTHOR INDEX A Abstract Abdullayev, R. A. Composition of normal traveltime curves and de termination of mean velocity to refracting boundaries with the aid of nomograms---------------------------------------------- 190-557 Abdullayev, R. N. Tectonics of the deep horizons of Lokbatan and the Khudat-Khachmas area of the cis-Caspian region from seis- mic prospecting data---------------------------------------- 189-581 Abe, Siro. See Fukushima, Naoshi. Abel, J. F., Jr. Ice tunnel closure phenomena------------------ 191-681 Abelson, F. H. See Haering, T. C. Abubaker, Iya. Disturbance due to a line source in a semi-infinite transversely isotropic elastic medium------------------------ 191-154 --Scattering of plane elastic waves at rough surfaces. I. -------- 188-200 Academia Sinica. A direct current amplifier of the modulation type for the telluric current method of geophysical prospecting 188-146 Ackerman, R. K. See Ralph, E.