A Census of Street Vendors in Ethekwini Municipality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durban the PLANNING of CATO MANOR

THE PLANNING OF CATO MANOR: LESSONS FOR THE SUSTAINABLE RECONSTRUCTION OF SOUTH AFRICAN CITIES by Zarina Patel Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the d~gree of Master of Science in the Department of Geographical and Environmental Sciences University of Natal Durban 1995 PREFACE The work described in this thesis was carried out in the Department of Geographical and Environmental . Sciences, University of Natal, Durban from February 1993 to September 1994. The thesis was completed in the Centre for Social and Development Studies between October 1994 and July 1995. The project was supervised by Dr. Debra Roberts dqring 1993, and co-supervised by Dr. 1. Robinson. Supervision changed hands in 1994, when Dr. 1. Robinson played the role of supervisor, and Dr. W. Ellery, co-supervisor. These studies represent original work by the author, and have not been submitted in any form to another university. Where use was made of the work of others, it has been duly acknowledged in the text. z. Patel ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A project of this length could not have been completed in isolation. I would like to thank the following people for making this thesis a reality: * To my supervisors: Debra, for helping me with the initial conceptualisation of the project and for showing me how my sensitivity towards the environment could be used constructively. Jenny, for your enthusiasm, encouragement and friendship during this arduous time. Your insights and comments have been invaluable. Fred, for taking me on, and for your keen editing eye. * My family: Thanks for giving me the space to be me, and for giving me the opportunity to get on with the job. -

ETHEKWINI MEDICAL HEALTH Facilitiesmontebellomontebello Districtdistrict Hospitalhospital CC 88 MONTEBELLOMONTEBELLO

&& KwaNyuswaKwaNyuswaKwaNyuswa Clinic ClinicClinic MontebelloMontebello DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC 88 ETHEKWINI MEDICAL HEALTH FACILITIESMontebelloMontebello DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC 88 MONTEBELLOMONTEBELLO && MwolokohloMwolokohlo ClinicClinic (( NdwedweNdwedweNdwedwe CHC CHCCHC && GcumisaGcumisa ClinicClinic CC MayizekanyeMayizekanye ClinicClinic BB && && ThafamasiThafamasiThafamasi Clinic ClinicClinic WosiyaneWosiyane ClinicClinic && HambanathiHambanathiHambanathi Clinic ClinicClinic && (( TongaatTongaatTongaat CHC CHCCHC CC VictoriaVictoriaVictoria Hospital HospitalHospital MaguzuMaguzu ClinicClinic && InjabuloInjabuloInjabuloInjabulo Clinic ClinicClinicClinic A AAA && && OakfordOakford ClinicClinic OsindisweniOsindisweni DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC EkukhanyeniEkukhanyeniEkukhanyeni Clinic ClinicClinic && PrimePrimePrime Cure CureCure Clinic ClinicClinic && BuffelsdraaiBuffelsdraaiBuffelsdraai Clinic ClinicClinic && RedcliffeRedcliffeRedcliffe Clinic ClinicClinic && && VerulamVerulamVerulam Clinic ClinicClinic && MaphephetheniMaphephetheni ClinicClinic AA &’&’ ThuthukaniThuthukaniThuthukani Satellite SatelliteSatellite Clinic ClinicClinic TrenanceTrenanceTrenance Park ParkPark Clinic ClinicClinic && && && MsunduzeMsunduze BridgeBridge ClinicClinic BB && && WaterlooWaterloo ClinicClinic && UmdlotiUmdlotiUmdloti Clinic ClinicClinic QadiQadi ClinicClinic && OttawaOttawa ClinicClinic && &&AmatikweAmatikweAmatikwe Clinic ClinicClinic && CanesideCanesideCaneside Clinic ClinicClinic AmaotiAmaotiAmaoti Clinic -

Provincial Road Network

D O 5 L Mziwamandla S Umgijimi LP 4 0 D Esiphethwini P Sizwakele P 5 Inkanyezi CP 2 2 98 Esiphetheini P 8 1 3 Bavumile JP 2 5 4 Sukuma CP Emthethweni P 2 2 Duze Cp Santa Francesca C 2 7 P2 0 986 P D368 1-1 L D O L0 O 2 Durban Prep H OL 216 Gokul P 02226 215 Ogwini Comp Arden P OL02 Saphinda Hp Umbelebele S L 02213 29 227 OL Ekuthuthukeni L02 O Ndonyela Js 16 O L O 0 5 P1 0 L 2 2 5 - 2 Sithandiwe LP Ispingo P 2 0 !. R603 2 139 Dbn For The 2 2 2 2 2 L1 - 1 1 0 N 2 Reunion Rocks 7 2 L Sishosonke H Hearing O Qhosheyiphethe LP 9 N L0 O Ekudeyeni Hp Bhekithemba Cp R603 Kwagwegwe 2222 5 Isipingo 1 0 Bashokuhle Hp Empaired 1 2 Shumayela H !. Intinyane L Kwamathanda S 7 Basholuhle P Badelile Isipingo S Masuku LP L 5 Lugobe H Mboko Hp Cola LP 72 Empusheni LP P 4 Khalipha P !. Umbumbulu 7 1578 P21-2 2 Phindela Sp L P21-2 23 1 Primrose P 2 L Isipingo P Sibusisiwe 02 L1276 Emafezini LP L OL02221 !. Comp H O 1-2 Alencon P P70 Khayelifile Hs P2 Malukazi R603 Phuphuma LP Siphephele Js Isipingo OL02224 P80 Mklomelo LP P80 R603 Zenzele P Hills P Tobi Hp P P80 Hamilton S 21 Sobonakhona H Folweni Ss Dabulizizwe Hp Celubuhle Hp 2 L -2 Zwelihle Js 4 L86 86 4 2 ETH 4 183 Igagasi H - L0 Thamela LP 2 L N O 3 1 1 Isipingo L1 L 6 0 - 878 0 8 Windey Heights P 7 2 L 9 Khiphulwazi P Kamalinee P 9 Beach P 22 4 219 Folweni 5 Emangadini Cp L02 !. -

From Mission School to Bantu Education: a History of Adams College

FROM MISSION SCHOOL TO BANTU EDUCATION: A HISTORY OF ADAMS COLLEGE BY SUSAN MICHELLE DU RAND Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in the Department of History, University of Natal, Durban, 1990. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Page i ABSTRACT Page ii ABBREVIATIONS Page iii INTRODUCTION Page 1 PART I Page 12 "ARISE AND SHINE" The Founders of Adams College The Goals, Beliefs and Strategies of the Missionaries Official Educational Policy Adams College in the 19th Century PART II Pase 49 o^ EDUCATION FOR ASSIMILATION Teaching and Curriculum The Student Body PART III Page 118 TENSIONS. TRANSmON AND CLOSURE The Failure of Mission Education Restructuring African Education The Closure of Adams College CONCLUSION Page 165 APPENDICES Page 170 BIBLIOGRAPHY Page 187 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Paul Maylam for his guidance, advice and dedicated supervision. I would also like to thank Michael Spencer, my co-supervisor, who assisted me with the development of certain ideas and in supplying constructive encouragement. I am also grateful to Iain Edwards and Robert Morrell for their comments and critical reading of this thesis. Special thanks must be given to Chantelle Wyley for her hard work and assistance with my Bibliography. Appreciation is also due to the staff of the University of Natal Library, the Killie Campbell Africana Library, the Natal Archives Depot, the William Cullen Library at the University of the Witwatersrand, the Central Archives Depot in Pretoria, the Borthwick Institute at the University of York and the School of Oriental and African Studies Library at the University of London. -

The Significance of Rural Areas in South Africa For

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF RURAL AREAS IN SOUTH AFRICA FOR TOURISM DEVELOPMENT THROUGH COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO UMGABABA, A RURAL AREA LOCATED IN THE PROVINCE OF KWAZULU-NATAL by MOHAN GOPAUL Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject GEOGRAPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR. A.C. HARMSE November 2006 ii Student number: 675-933-5 I declare that, “The significance of rural areas in South Africa for tourism development through community participation with special reference to Umgababa, a rural area located in the province of KwaZulu-Natal” is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ……………………… …………………. SIGNATURE DATE (MR. M. GOPAUL) iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the following people whose contributions and support have been invaluable: Dr. A.C. Harmse, my supervisor for her superb supervision of the thesis. Ms. Melanie Nicolau, Head of Department, Department of Geography, Unisa, for her mediation in times of problems and continued assistance until completion of the thesis. Ms. Leanne Brown, subject librarian at Unisa, for her prompt service. Ms. Helenne Steenkamp, secretary at the Department of Geography, Unisa, for her prompt service with regards to communication. Ms. Noeline McNamara, from eThekwini Municipality, South Local Council, assisting with some of the maps. Radhika Gopaul (my wife) for typing and layout of the thesis. Arusha and Kerina (my daughters) for their continued support and patience during the writing process. Suren Bisseru, Simunye Printers, for binding this thesis. -

The Legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli's Christian-Centred Political

Faith and politics in the context of struggle: the legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli’s Christian-centred political leadership Simangaliso Kumalo Ministry, Education & Governance Programme, School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa Abstract Albert John Mvumbi Luthuli, a Zulu Inkosi and former President-General of the African National Congress (ANC) and a lay-preacher in the United Congregational Church of Southern Africa (UCCSA) is a significant figure as he represents the last generation of ANC presidents who were opposed to violence in their execution of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. He attributed his opposition to violence to his Christian faith and theology. As a result he is remembered as a peace-maker, a reputation that earned him the honour of being the first African to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Also central to Luthuli’s leadership of the ANC and his people at Groutville was democratic values of leadership where the voices of people mattered including those of the youth and women and his teaching on non-violence, much of which is shaped by his Christian faith and theology. This article seeks to examine Luthuli’s legacy as a leader who used peaceful means not only to resist apartheid but also to execute his duties both in the party and the community. The study is a contribution to the struggle of maintaining peace in the political sphere in South Africa which is marked by inter and intra party violence. The aim is to examine Luthuli’s legacy for lessons that can be used in a democratic South Africa. -

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC of SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA November Vol. 641 Pretoria, 9 2018 November No. 42025 PART 1 OF 2 LEGAL NOTICES A WETLIKE KENNISGEWINGS ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 42025 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 42025 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 9 NOVEMBER 2018 IMPORTANT NOTICE: THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING WORKS WILL NOT BE HELD RESPONSIBLE FOR ANY ERRORS THAT MIGHT OCCUR DUE TO THE SUBMISSION OF INCOMPLETE / INCORRECT / ILLEGIBLE COPY. NO FUTURE QUERIES WILL BE HANDLED IN CONNECTION WITH THE ABOVE. Table of Contents LEGAL NOTICES BUSINESS NOTICES • BESIGHEIDSKENNISGEWINGS Gauteng ....................................................................................................................................... 12 KwaZulu-Natal ................................................................................................................................ 13 Mpumalanga .................................................................................................................................. 13 North West / Noordwes ..................................................................................................................... 14 Northern Cape / Noord-Kaap ............................................................................................................. 14 Western Cape / Wes-Kaap ............................................................................................................... -

Lessons from the Impacts of an Environmental Offsets on the Durban Aerotropolis Master Plan from a Spatial Planning Perspective

Lessons from the impacts of an Environmental Offsets on the Durban Aerotropolis Master Plan from a Spatial Planning perspective. Authors: Letebele, Emmanuel and Nkosi, Sabelo B. eThekwini Municipality, Development Planning, Environment and Management Unit, 166 KE Masinga Road, Durban, 4001, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa The paper will be presented under the Session: 15a Integrating biodiversity and ecosystem services into the mitigation hierarchy Introduction The City of Durban within eThekwini Municipality is located on the east coast of South Africa in the province of KwaZulu Natal (Figure 1). Durban is a modern multi-faceted fast growing metropolitan city within eThekwini Municipality. King Shaka International Airport is situated within the Northern Municipal Region and it is the core of the proposed Durban Aerotropolis City. The Durban Aerotropolis Master Plan is in the process of being developed. This plan seeks to promote the appropriate development of land around the airport and to ensure planning alignment between various government departments. The Durban Aerotropolis Master Plan is founded on a series of different study areas ranging from a 1 hour travel distance to King Shaka International Airport, to a series of Satellite Zones, to the Aerotropolis “core”, which is also referred to as the Aerotropolis City. The focus area for this paper will be the Aerotropolis City with King Shaka International Airport (KSIA) as the core of the Aerotropolis City. Figure 1: The location of Durban within the eThekwini Municipal Area in the province of KwaZulu Natal, South Africa (Source: EThekwini Municipality Figure 2: The location of the proposed Durban Aerotropolis Core (highlighted in Blue below) in relation to the Northern Municipal Region. -

Lower Umkhomazi Bulk Water Supply System – Water Supply Scheme in Kwazulu-Natal

LOWER UMKHOMAZI BULK WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM – WATER SUPPLY SCHEME IN KWAZULU-NATAL SCOPING REPORT AUGUST 2017 DRAFT PREPARED FOR: UMGENI WATER Title and Approval Page Lower uMkhomazi Bulk Water Supply System – Water Supply Scheme in Project Name: KwaZulu-Natal Report Title: Scoping Report Authority Reference: Not Yet Assigned Report Status: Draft Applicant: Umgeni Water Prepared By: Nemai Consulting +27 11 781 1730 147 Bram Fischer Drive, +27 11 781 1731 FERNDALE, 2194 [email protected] PO Box 1673, SUNNINGHILL, www.nemai.co.za 2157 10579-20170815-Draft Scoping Report Reference: R-PRO-REP|20170216 Report Authorisation Name Signature Date Author: Samantha Gerber 07/08/2017 Reviewer: Donavan Henning 11/08/2017 This Document is Confidential Intellectual Property of Nemai Consulting C.C. © copyright and all other rights reserved by Nemai Consulting C.C. This document may only be used for its intended purpose LUBWSS – Water Supply Scheme Scoping Report Draft Amendments Page Amendment Date: Nature of Amendment Number: 29 August 2017 Draft Report for 30-Day Authority and Public Review 00 LUBWSS – Water Supply Scheme Scoping Report Draft Executive Summary The current water resources supplying the South Coast of KwaZulu-Natal are insufficient to meet the projected water demands. The Lower uMkhomazi Bulk Water Supply System is the recommended augmentation option for the existing Upper and Middle South Coast Supply area. Therefore, Umgeni Water propose to construct the Lower uMkhomazi Bulk Water Supply System – Water Supply Scheme in order to increase the assurance of water supply. The project area is situated in the eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality in KwaZulu-Natal. -

Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities

Public Disclosure Authorized Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities ETHEKWINI, SOUTH AFRICA Urban Environmental Profile Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities ETHEKWINI, SOUTH AFRICA Urban Environmental Profile COPYRIGHT © 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. February 2016 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Publishing and Knowledge Division, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities, Urban Environmental Profile for eThekwini, South Africa was prepared by a core study team led by Roland White (Global Lead: City Management, Governance and Financing - Task Team Leader) and included Chyi-Yun Huang (Urban Specialist) and a consultant team from AECOM including John Bachmann, Diane Dale, Brian Goldberg, Maritza Pechin and Dr. -

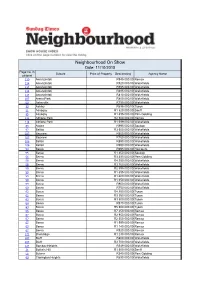

Neighbourhood on Show Date: 11/10/2015 Page No

Neighbourhood On Show Date: 11/10/2015 Page no. in Suburb Price of Property Descending Agency Name editorial 110 Amanzimtoti R945 000.00 Remax 114 Amanzimtoti R520 000.00 Wakefields 114 Amanzimtoti R595 000.00 Wakefields 114 Amanzimtoti R685 000.00 Wakefields 114 Amanzimtoti R810 000.00 Wakefields 107 Arena Park R800 000.00 Wakefields 60 Asherville R795 000.00 Wakefields 33 Ashley R695 000.00 Tyson 21 Assagay R1 520 000.00 Seeff 35 Assagay R1 895 000.00 Pam Golding 111 Athlone Park R2 500 000.00 Remax 114 Athlone Park R1 599 000.00 Wakefields 83 Avoca R995 000.00 Soukop 97 Ballito R3 500 000.00 Wakefields 107 Bayview R650 000.00 Wakefields 107 Bayview R750 000.00 Wakefields 106 Bellair R890 000.00 Wakefields 106 Bellair R990 000.00 Wakefields 53 Berea R995 000.00 Harcourts 55 Berea R1 450 000.00 Soukop 56 Berea R3 495 000.00 Pam Golding 58 Berea R4 950 000.00 Wakefields 58 Berea R3 700 000.00 Wakefields 58 Berea R2 995 000.00 Wakefields 59 Berea R1 895 000.00 Wakefields 59 Berea R1 600 000.00 Wakefields 59 Berea R1 050 000.00 Wakefields 59 Berea R900 000.00 Wakefields 60 Berea R750 000.00 Wakefields 62 Berea R4 950 000.00 Tyson 62 Berea R3 950 000.00 Tyson 63 Berea R3 500 000.00 Tyson 64 Berea R570 000.00 Tyson 64 Berea R5 900 000.00 Tyson 66 Berea R7 250 000.00 Remax 67 Berea R2 950 000.00 Remax 67 Berea R2 350 000.00 Remax 67 Berea R1 999 000.00 Remax 67 Berea R1 140 000.00 Remax 67 Berea R920 000.00 Remax 121 Blackridge R1 230 000.00 Remax 107 Bluff R800 000.00 Wakefields 107 Bluff R3 700 000.00 Wakefields 124 Bombay Heights R549 000.00 -

List of Outstanding Trc Beneficiaries

List of outstanding tRC benefiCiaRies JustiCe inVites tRC benefiCiaRies to CLaiM tHeiR finanCiaL RePaRations The Department of Justice and Constitutional Development invites individuals, who were declared eligible for reparation during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission(TRC), to claim their once-off payment of R30 000. These payments will be eff ected from the President Fund, which was established in accordance with the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act and regulations outlined by the President. According to the regulations the payment of the fi nal reparation is limited to persons who appeared before or made statements to the TRC and were declared eligible for reparations. It is important to note that as this process has been concluded, new applications will not be considered. In instance where the listed benefi ciary is deceased, the rightful next-of-kin are invited to apply for payment. In these cases, benefi ciaries should be aware that their relationship would need to be verifi ed to avoid unlawful payments. This call is part of government’s attempt to implement the approved TRC recommendations relating to the reparations of victims, which includes these once-off payments, medical benefi ts and other forms of social assistance, establishment of a task team to investigate the nearly 500 cases of missing persons and the prevention of future gross human rights violations and promotion of a fi rm human rights culture. In order to eff ectively implement these recommendations, the government established a dedicated TRC Unit in the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development which is intended to expedite the identifi cation and payment of suitable benefi ciaries.