Durban the PLANNING of CATO MANOR

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

1072 24-12 Kzng11

KWAZULU-NATAL PROVINCE RKEPUBLICWAZULU-NATAL PROVINSIEREPUBLIIEK OF VAN SOUTHISIFUNDAZWEAFRICA SAKWAZULUSUID-NATALI-AFRIKA Provincial Gazette • Provinsiale Koerant • Igazethi Yesifundazwe GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY—BUITENGEWONE KOERANT—IGAZETHI EYISIPESHELI (Registered at the post office as a newspaper) • (As ’n nuusblad by die poskantoor geregistreer) (Irejistiwee njengephephandaba eposihhovisi) PIETERMARITZBURG, 24 DECEMBER 2013 Vol. 7 24 DESEMBER 2013 No. 1072 24 kuZIBANDLELA 2013 We oil hawm he power to preftvent kllDc AIDS HEIRINE 0800 012 322 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Prevention is the cure N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 306319—A 1072—1 2 Extraordinary Provincial Gazette of KwaZulu-Natal 24 December 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. Page No. ADVERTISEMENT Road Carrier Permits, Pietermaritzburg........................................................................................................................ -

DURBAN NORTH 957 Hillcrest Kwadabeka Earlsfield Kenville ^ 921 Everton S!Cteelcastle !C PINETOWN Kwadabeka S Kwadabeka B Riverhorse a !

!C !C^ !.ñ!C !C $ ^!C ^ ^ !C !C !C!C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C $ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ ñ!C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^ !C ^ !C ñ!C !C ^ ^ !C !C $ ^!C $ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C ñ!.^ $ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C $ !C !C ñ $ !. !C !C !C !C !C !C !. ^ ñ!C ^ ^ !C $!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !. !C !C ñ!C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ ^ $ ^ !C ñ !C !C !. ñ ^ !C !. !C !C ^ ñ !. ^ ñ!C !C $^ ^ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !C !. ñ !C !C ^ !C ñ!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C !. !C ^ !. !. !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ñ !C !. -

SAARF OHMS 2006 Database Layout

SAARF OUTDOOR MEASUREMENT SURVEY PRIVATE & CONFIDENTIAL Outdoor Database Layout South Africa (GAUTENG & KWAZULU-NATAL) August 2007 FILES FOR COMPUTER BUREAUX Prepared for: - South African Advertising Research Foundation (SAARF) Prepared by: - Nielsen Media Research and Nielsen Outdoor Copyright Reserved Confidential 1 The following document describes the content of the database files supplied to the computer bureaux. The database includes four input files necessary for the Outdoor Reach and Frequency algorithms: 1. Outdoor site locations file (2 – 3PPExtracts_Sites) 2. Respondent file (2 – 3PPExtracts_Respondents) 3. Board Exposures file (2 – Boards Exposure file) 4. Smoothed Board Impressions file (2 – Smoothed Board Impressions File) The data files are provided in a tab separated format, where all files are Window zipped. 1) Outdoor Site Locations File Format: The file contains the following data fields with the associated data types and formats: Data Field Max Data type Data definitions Extra Comments length (where necessary) Media Owner 20 character For SA only 3 owners: Clear Channel, Outdoor Network, Primedia Nielsen Outdoor 6 integer Up to a 6-digit unique identifier for Panel ID each panel Site type 20 character 14 types. (refer to last page for types) Site Size 10 character 30 size types (refer to last pages for sizes) Illumination hours 2 integer 12 (no external illumination) 24 (sun or artificially lit at all times) Direction facing 2 Character N, S, E, W, NE, NW, SE, SW Province 25 character 2 Provinces – Gauteng , Kwazulu- -

A Census of Street Vendors in Ethekwini Municipality

A Census of Street Vendors in eThekwini Municipality Final Consolidated Report Submitted to: StreetNet International, Durban 30 September 2010 A Census of Street Vendors in eThekwini Municipality Final Consolidated Report Submitted to: StreetNet International, Durban Submitted by: Reform Development Consulting Authors: Jesse McConnell (Director – RDC), Amy Hixon (Researcher – RDC), Christy McConnell (Senior Researcher – RDC) Contributors: Gabrielle Wills (Research Associate – RDC), Godwin Dube (Research Associate – RDC) Project Advisory Committee: Sally Roever, Sector Specialist: Street Trading – WIEGO Caroline Skinner, Urban Policies Programme Director – WIEGO; Senior Researcher – African Centre for Cities at the University of Cape Town Richard Dobson – Asiye Etafuleni consultancy Patrick Ndlovu – Asiye Etafuleni consultancy Gaby Bikombo – StreetNet Winnie Mitullah – University of Nairobi Nancy Odendaal, Project Coordinator – Association of African Planning Schools (AAPS), African Centre for Cities at the University of Cape Town Reform Development Consulting 271 Cowey Road +27 (0)31 312 0314 Durban, 4001 [email protected] South Africa www.reformdevelopment.org Consolidated Census Report Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... VII 1. PREFACE ................................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... -

Community Safety Initiative: Chesterville OVERVIEW

Community Safety Initiative: Chesterville OVE R VIE W • Bursary • School Partnership • After-School Sport • Street Committees • 1-Stop Centre I. PROGRAMME TITLE: Community Safety Initiative: Chesterville Pilot Programme II. IMPLEMENTING ORGANISATION: Vukukhanye III. POSTAL ADDRESS IV. PHYSICAL ADDRESS P.O Box 567 Suite 17B Westville Centre Westville 52 Norfolk Terrace 3630 Westville, 3629 KwaZulu-Natal KwaZulu-Natal South Africa South Africa V. CONTACT PERSONS CEO Vukukhanye - Anthony van der Meulen Telephone : +27 (0)31 266 2288 Cell : 083 233 2924 Email : [email protected] Chairman Vukukhanye - Craig Coombe Telephone : +27 (0)31 566 1484 Cell : 082 610 5585 Email : [email protected] Chesterville Residents Association - Zamo Ngobese Telephone : +27 (0)31 311 3227 Cell : 084 957 5660 Email : [email protected] VI. OFFICE CONTACT DETAILS Telephone : +27 (0)31 266 2288 Email : [email protected] Fax : +27 (0)31 266 5115 Website : http://www.vukukhanye.org Vukukhanye/Community Safety Initiative: Chesterville/ Proposal, April 2009…Page 1 of 11 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Vukukhanye is a registered public benefit and non-profit organization, which is committed to community development through community partnership, leadership development and empowerment. Vukukhanye’s Management Board and project team members have a nearly twenty year history of working alongside the community of Chesterville, which is located in the Cato Manor region of the Ethekwini Municipal Area. Vukukhanye, in collaboration with local business, government and civil society, are partnering with the Chesterville Residents Association in the implementation of a Community Safety Initiative. The aim of this Programme is not only a reduction in crime, but also the continued holistic development of this historically disadvantaged community, where crime and other socio- economic stresses are high. -

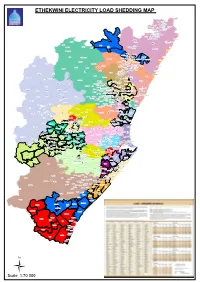

Ethekwini Electricity Load Shedding Map

ETHEKWINI ELECTRICITY LOAD SHEDDING MAP Lauriston Burbreeze Wewe Newtown Sandfield Danroz Maidstone Village Emona SP Fairbreeze Emona Railway Cottage Riverside AH Emona Hambanathi Ziweni Magwaveni Riverside Venrova Gardens Whiteheads Dores Flats Gandhi's Hill Outspan Tongaat CBD Gandhinagar Tongaat Central Trurolands Tongaat Central Belvedere Watsonia Tongova Mews Mithanagar Buffelsdale Chelmsford Heights Tongaat Beach Kwasumubi Inanda Makapane Westbrook Hazelmere Tongaat School Jojweni 16 Ogunjini New Glasgow Ngudlintaba Ngonweni Inanda NU Genazano Iqadi SP 23 New Glasgow La Mercy Airport Desainager Upper Bantwana 5 Redcliffe Canelands Redcliffe AH Redcliff Desainager Matata Umdloti Heights Nellsworth AH Upper Ukumanaza Emona AH 23 Everest Heights Buffelsdraai Riverview Park Windermere AH Mount Moreland 23 La Mercy Redcliffe Gragetown Senzokuhle Mt Vernon Oaklands Verulam Central 5 Brindhaven Riyadh Armstrong Hill AH Umgeni Dawncrest Zwelitsha Cordoba Gardens Lotusville Temple Valley Mabedlane Tea Eastate Mountview Valdin Heights Waterloo village Trenance Park Umdloti Beach Buffelsdraai Southridge Mgangeni Mgangeni Riet River Southridge Mgangeni Parkgate Southridge Circle Waterloo Zwelitsha 16 Ottawa Etafuleni Newsel Beach Trenance Park Palmview Ottawa 3 Amawoti Trenance Manor Mshazi Trenance Park Shastri Park Mabedlane Selection Beach Trenance Manor Amatikwe Hillhead Woodview Conobia Inthuthuko Langalibalele Brookdale Caneside Forest Haven Dimane Mshazi Skhambane 16 Lower Manaza 1 Blackburn Inanda Congo Lenham Stanmore Grove End Westham -

Camperdown NU Umzinto NU Inanda NU Inanda NU Lower

New Hanover NU Hoqweni Menyane Mayesweni Hlomantethe Lower Tugela NU KwaHlwemini Sonkonbo/Esigodi Mkhomazi Engoleleni Thongathi Lower Tugela NU Swayimana W osiyane Village Mnamane/ Usuthu Shudu New Hanover NU Emnamane Indaka Mnyameni Umhlali Beach Mambedwini Hengane Mangangeni Mona KwaSokesimbone Ukhalo/Mhlungwini Nqwayini Msunduze Lower Tugela NU Thompson's Bay KwaMophumula Trust Feed Inhlabamkhosi Ndondolo Nobanga Deepdene Makhuluseni Lauriston Deepdale Odlameni Ndwedwe Newtown Ngedleni 6 Burbreeze W ewe Ikhohlwa Sandfield Umsinduzi Mission Reserve Ballito Bay Vuka Nonoti Gcumisa SP Hambanathi Ext 4 Maidstone Village Msilili Mthembeni Magwaveni Pietermaritzburg NU Esthezi Emona SP Fairbreeze Shangase Village Tugela Intaphuka Emona Riverside AH Railway Cottage Ezindlovini Hambanathi Ext 1 Cuphulaka Ziweni Ekhukanyeni W hiteheads Vanrova Gardens Dores Flats Mapumulu SP Mbhukubhu Hillview Tongaat CBD Kwazini Inanda NU Gandhinagar Tongaat Central Ngabayena Ezibananeni Mdlonti Trurolands Mithanagar Maqomgoo Ogunjini Belvedere Imeme 61 W atsonia Tongova M ews Mbhava Mgezanyoni Buffelsdale Chelmsford Heights Tongaat Beach Table Mountain Kwasumubi Nonzila Mbeka Mgezanyoni Inanda Makapane W estbrook Bhulushe Hazelmere Pietermaritzburg NU Amatata Jojweni Gunjini Ngudlintaba New Glasgow Ngonweni Enbuyeni 60 Genazano Cuphulaka Iqadi SP New Glasgow Nkanyezini La M ercy Airport Mdluli SP Abehuzi Amatata Desainager Upper Bantwana Ashburton Training Centre Mlahlanja Mdaphuma Mlahlanja 59 Redcliffe Nkanyezini Canelands Inanda NU 58 Umdloti Heights Ophokweni -

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites

Accredited COVID-19 Vaccination Sites Kwa- Zulu Natal Permit Number Primary Name Address 202102308 Medirite Pharmacy cnr Allen & Oak Street Castle Rock Amajuba DM KwaZulu-Natal 202100770 Medirite Newcastle 24 Victoria Street Pharmacy Amajuba DM KwaZulu-Natal 202102410 Glenmed Pharmacy Shop 7 Sanlam Plein Building; 51868 De Beer Street, Glencoe 2930 Umzinyathi DM KwaZulu-Natal 202101228 Umgeni Waterfall Old Main Road Howick Institute Hospital uMgungundlovu DM KwaZulu-Natal 202103781 Benedictine Gateway Zululand DM Clinic KwaZulu-Natal 202100289 Gamalakhe CHC Off Ray Nkonyeni Rd Cnr Michael Nsimbi&Rev Sithole Street Gamalakhe Ugu DM KwaZulu-Natal 202100329 Life Empangeni Prv Cnr Biyela and Ukuli Hosp Streets King Cetshwayo DM KwaZulu-Natal 202102151 Hashmed Pharmacy 37 Sol Harris Crescent Shop 2 eThekwini MM KwaZulu-Natal 202103489 Ballims Pharmacy 450 Church Street uMgungundlovu DM KwaZulu-Natal 202103737 Dr IM Omar GP 178 umgeni road, Greyville, Durban eThekwini MM KwaZulu-Natal 202101205 Rietvlei Hospital R56 Rietvlei Location Harry Gwala DM KwaZulu-Natal Updated: 30/06/2021 202100455 Chatsworth Township 6 Main Street, Area Centre Clinic Park Chatsworth eThekwini MM KwaZulu-Natal 202103409 Nongoma Bliss Main Street Pharmacy eThekwini MM KwaZulu-Natal 202101226 Estcourt Hospital Old Main Road Uthukela DM KwaZulu-Natal 202101355 Havenside Pharmacy 10 Havenside Shopping Centre eThekwini MM KwaZulu-Natal 202103096 Clicks Pharmacy Jozini Umkhanyakude DM Mall KwaZulu-Natal 202103459 DR RS PILLAY Parklands Medical Centre eThekwini MM KwaZulu-Natal -

F F Load Schedule

REVISED LOAD - SHEDDING SCHEDULE EFFECTIVE 7 APRIL 2015 New requirements by Eskom, technical reliability and feedback from our customers have necessitated a revision of the existing schedule. The new schedule entails switching off widespread areas at our High Voltage Substations and seeks to minimise interruptions and introduce more fairness in the allocation of Blocks. It will also reduce the incidence of customer Block changes due to network faults. Each High Voltage Substation is categorised as largely Residential, largely Commercial or largely Industrial. A point to note is that some Residential or Commercial customers may be categorised as Industrial and fall within these Blocks and vice versa. It is difficult to correctly categorise each individual customer owing to the nature of the electrical network i.e. interconnectivity, hence we can expect some discrepancies. The new schedule consists of four stages with the rotation in the most likely period of load-shedding (06:00 - 22:00, Monday to Saturday) as follows :- Stage 1 : Residential/Commercial Blocks - load-shed once every second day Stage 2 : Residential/Commercial Blocks - load-shed once every day Stage 3 : Residential/Commercial/Industrial Blocks - load-shed once every day Stage 4 : Residential/Commercial/Industrial Blocks - load-shed once every day. Residential and Commercial will be shed for an additional block on alternate days All Blocks are scheduled for a 2 hour outage with an additional 30 minutes contingency to cater for switching. Sometimes, technical difficulties in restoring electricity may occur and should a customer remain off for a substantial amount of time after the Block has been scheduled to be restored, then that incident must be treated as a fault and reported to the Electricity Contact Centre on 080 1313 111. -

1978. | the Statistics of Extreme Values and the Analysis of Floods in South Africa, Technical Report No

Adamson, P.T., | 1978. | The statistics of extreme values and the analysis of floods in South Africa, Technical Report No. TR 86, Department of Water Affairs, Pretoria, 187 p. | [FLOO] Adamson, P.T. and Pegram, G.G.S., | 1988. | Research needs for flood peak regionalization in South Africa, Conference on Floods in Perspective/Vloede in Perspektief, Division of Hydraulic and Water Engineering of the South African Institution of Civil Engineers and the CSIR, 20-21 October 1988, Pretoria, 15 p. | [FLOO] Alcock, P., | 1980. | Some aspects of Black South Easters over the southern and eastern Cape Province, South Africa, B.Sc. (Hons) Seminar, Department of Geography, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, 15 p. | [FLOO] Alcock, P., | 1981. | Black South-easter and floods: what you can do to avoid damage, Farming Digest, No. 10, June 1981, p. 32-35. | [FLOO] Alexander, W.J.R., | 1971. | Floods in the eastern Cape - August 1971, Civil Engineer in South Africa, VOL 13(12), p. 450-451. | [FLOO] Alexander, W.J.R., | 1981. | Guidelines for development within areas susceptible to flooding, Technical Report No. TR 112, Department of Water Affairs, Forestry and Environmental Conservation, Pretoria, 11 p. | [FLOO] Alexander, W.J.R., | 1981. | The Laingsburg flood of 25th January 1981, Municipal Engineer, VOL 12(2), p. 11-20. | [FLOO] Alexander, W.J.R., | 1988. | Flood hydrology: are we addressing the real issues?, Conference on Floods in Perspective/Vloede in Perspektief, Division of Hydraulic and Water Engineering of the South African Institution of Civil Engineers and the CSIR, 20-21 October 1988, Pretoria, 12 p. | [FLOO] Alexander, W.J.R., | 1993. -

Ethekwini West New Germany Palmiet 1120 Mophela Mine 937 Ext Park ^ 17718 Mpumalanga C Zamani !C PINETOWN !

!C !C^ ñ!.!C !C $ !C^ ^ ^ !C !C !C!C !C !C !C ^ ^ !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C ^ !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ ñ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C $ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C ñ !C !C !C ^ !C !.ñ ñ!C !C !C !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ñ !C !C ^ ^ !C !C !. !C !C ñ ^ !C ^ !C ñ!C !C ^ ^ !C !C $ ^!C $ ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C ñ!.^ $ !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C $ !C ^ !C !C $ !C !C ñ $ !. !C !C !C !C !C !C !. ^ ñ!C ^ ^ !C $!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !. !C !C ñ!C !C !C !C ^ñ !C !C ñ !C !C !. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C ñ ^ $ ^ !C ñ !C !C!. ñ ^ !C !. !C !C ^ !. ^ ñ ñ!C !C $^ ^ ^ !C ^ ñ ^ !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !. !C ^ !C $ !C !. ñ !C !C ^ ñ!C!. ^ !C !C !C !C !C !C !C !C $!C !. !C ^ !. !. !C !C !. ^ !C !C ^ !C ^ !C !C ñ !C !. -

NHLS LABORATORIES TESTING SARS Cov 2 CONTACT DETAILS.Pdf

NHLS LABORATORIES AUTHORISED TO CONDUCT DIAGNOSTIC TESTING OF SARS CoV-2 (COVID 19) Province Laboratory Address Type of Test Contact Details East London Laboratory Frere Hospital, 1 Amalinda Road, East PCR and Antigen London. Matatiele Laboratory Taylor bequest Hospital, Matatiele, PCR and Antigen Ms Tabita Makula, Area Main Street, Matatiele Eastern Cape Manager: Eastern Cape, Nelson Mandela Academic/Walter Nelson Academic Hospital. Sisson PCR and Antigen 082 893 6875 Sisulu University Street, Fortgate, Mthata Port Elizabeth Provincial Port Elizabeth Hospital, Cnr PCR and Antigen Laboratory Buckingham and Eastern Manapo Laboratory Mofumahadi Manapo Mopeli PCR and Antigen Hospital, Mampoi Street, Phuthaditjaba Mr Jone Mofokeng, Area Pelonomi Laboratory Pelonomi Hospital, 121 Dr Belcher PCR and Antigen Free State Manager: Free State and Road, Heidedal, Bloemfontein North West, 082 603 2577 Universitas Academic Laboratory Room 433, 2nd Floor, Block E. Francois PCR and Antigen Retief Building, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein Braamfontein TB Laboratory National Health Laboratory Service, PCR and Antigen Mr Bahule Motlonye, Area Gauteng Cnr De Korte and Hospital Streets, Manager: Gauteng, 082 807 Braamfontein 2650 Province Laboratory Address Type of Test Contact Details Carltonville Laboratory Carltonville Ext 10 PCR Charlotte Maxeke Johanessburg NHLS, Charlotte Hospital, 7 York PCR Academic Laboratory Road, Parktown Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Chris Hani Hospital, Chris Hani Road, PCR Laboratory Zone 6, Diepkloof, SOWETO Dr George Mukhari Laboratory Sefako Makgatho Health Science PCR University, Virology Laboratory Dr Yusuf Dadoo Laboratory Cnr Hospital Road and memorial PCR Avenue, Krugersdorp, Helen Joseph Laboratory Helen Joseph Hospital, 1 Perth Road, Auckland Park, Johannesburg. Jubilee Laboratory Jubilee Hospital, 92 Jubilee Road, PCR Temba Rural.