Royal Historical Society of Queensland Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unauthorised History of ASTER LOCOMOTIVES THAT CHANGED the LIVE STEAM SCENE

The Unauthorised History of ASTER LOCOMOTIVES THAT CHANGED THE LIVE STEAM SCENE fredlub |SNCF231E | 8 februari 2021 1 Content 1 Content ................................................................................................................................ 2 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 3 1975 - 1985 .......................................................................................................................... 6 Southern Railway Schools Class .................................................................................................................... 6 JNR 8550 .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 V&T RR Reno ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Old Faithful ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Shay Class B ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 JNR C12 ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 PLM 231A ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Railway Locomotive and Rollingstock Drawings

Railway locomotive and rollingstock drawings Research Guide to Railway locomotive and rollingstock drawings records at Queensland State Archives Research Guide to Railway Locomotive and Rollingstock Drawings Records This research guide provides an overview of the drawings produced by or for the Chief Mechanical Engineer’s Branch (or Locomotive Branch) of the Railway Department. The drawings are available on microfilm at Queensland State Archives (QSA). These railway drawings trace the development of Queensland railway locomotive and rollingstock from 1864. Most of the drawings consist of general arrangement and working drawings for the construction of rollingstock. The QSA references for these records are in the Queensland State Archives’ catalogue. Note: QSA does not hold all drawings proposed for or adopted by Queensland Rail (QR). Queensland Rail Heritage Collection The Queensland Rail Heritage Collection consists of 72 series of records transferred to Queensland State Archives from the Workshops Rail Museum, Ipswich, in 2019. The QRHS spans the years 1864 to 2007. All the records are open. These holdings give us a glimpse into Queensland’s past with railway brass bands, railway refreshment rooms and clock repair registers. There are many treasures in the plans, drawings, photographs and audio-visual material. A search of our catalogue using the keywords - Queensland Rail Heritage Collection - will find all the series of records including hyperlinks to descriptions. Interested researchers are welcome to visit Queensland State Archives to request and view the records. Each series has a Queensland Rail/Queensland Museum catalogue number. A list in numerical order by catalogue numbers is in the Research Guide to railway records at Queensland State Archives. -

San Jac Trip to the Texas State Railroad

Vol . 41 N o. 4 The official MoNThly PublicaTioN of The SaN JaciNTo Model RailRoad club , i Nc .aPRil 2010 April Meeting The next meeting will be on April 6th, 2010. At Bayland Park Community Center. The Meeting starts at 7:00 pm. Program - The Railroads of Longleaf Louisiana by Everett Luck San Jac Trip to the Texas State Railroad A Ride on the Texas State Railroad Mark Couvillion We started our trip on a comfortable morning that promised a day of rain. The bus arrived on time and we only had to stop once to pick up a few stragglers. The route to Palestine seemed to be intended to get our train juices flowing, as we followed many back roads that seemed to parallel railroad tracks. We never saw a train, or even a single car in a siding or spur, on the entire trip. The weather deteriorated as we got closer to Palestine, with the most rain falling just as the bus stopped at the depot! The temperature had dropped noticeably, but the 33 deter - mined souls on the bus made a run for the depot. We quickly learned that our train would be pulled by #7, a 1947 Alco RS-2 in Black Widow Livery. Something was amiss with the steam engine scheduled to pull our train. Oh well, a first-generation Alco diesel is almost a steam en - gine, and in that paint scheme! The passengers huddled in the depot, trying to find a warm spot, as the station and all of the facilities are de - signed for warm-weather excursions. -

November-December 2014 Newsletter.Pub

NORTHERN DISTRICTS MODEL ENGINEERING SOCIETY (PERTH) INC. November—December 2014 Slight ‘changing of the guard’ at AGM NDMES’ AGM on October 10 saw a slight changing of the guard, with Paul James having to step down after reaching the mandatory three years as president. He was succeeded by Tom Winterbourn, but Paul will continue to serve the society as a committee member. Phil Gibbons was re-elected vice-president, but John Turney did not seek re-election as treasurer due to a forthcoming overseas work commitment. Damian Outram offered to fill the vacant position from the floor of the meeting and was duly elected. Paul Costall remains as secretary and party booking co- ordinator. With Ed Brown and Andrew Manning not seeking re-election as committee members, Steve Some familiar faces, including Jeff Clifton from Bunbury, enjoy Reeves, Geoff Wilkinson, Gilbert Ness and Paul James lunch in perfect weather at our inaugural Invitation Run on were elected to fill the four positions. September 13. More pictures and a report, pages 6 and 7... The AGM returning officer was John Shugg. The new president Tom Winterbourn thanked Paul for his leadership over the past three years, during which Other society positions filled included: there has been much progress, with the completion of Boiler inspectors: Phil Gibbons and Steve Reeves, the new 5” carriage storage shed, the 7¼” carriage shed/ with Noel Outram to be added when approval is workshop, the upgrade of the electrical system (overseen received from AMBSC president Barry Potter. by Andrew Manning), the re-flooring of the gazebo, Librarian: John Martin. -

Collection 598 Ray Collins Railroad Collection Inventory Box Folder

Collection 598 Ray Collins Railroad Collection Inventory Box Folder Description ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Instructional Books / Material: “Library of Steam Engineering”; Fehrenbatch; ca. 1920 “Practice of Lubrication”; T. C. Thomsen; 1920 “Shop Hints on Locomotive Valve Setting”; Jack Britton; 1926 “Elementary Principles of Diesel-Engine Construction”; Mechanic’s Institute of Boy’s Technical High School; 1936 “Elesco Locomotive Feed Water Heaters”; The Superheater Company; 1929 “Elesco Locomotive Feed Water Heaters”; The Superheater Company; 1925 “Elesco Locomotive Superheaters”; The Superheater Company; 1925 “Locomotive Boiler Feed Pump and Feed Water Heaters”; Worthington Corp.; 1925 “Diesel Power for Transportation”; Machinists’ Monthly Journal; 1939 Diesel Mechanics Trade Extension Course Notebook; n.d. Diesel Maintenance Data; n.d. Audio Tapes on 7 inch reels: “A Farewell To Steam”; High Fidelity Recordings; ca. 1960 “Narrow Gauge Rail Road Sounds, Denver & Rio Grande Western Durango Division”; Freight Trains Album No.1; Southwest Sounds Co.; n.d. “Narrow Gauge Rail Road Sounds, Denver & Rio Grande Western Durango Division”; Passenger Trains Album No.1; Southwest Sounds Co.; n.d.. Recording of “Symphony in Steam” and “American Freedom Train” by A.R. Collins; 1977 Recording of LP Albums “Reading Steam Vol. 2” and “Extra 4449 North” by A.R. Collins; 1977 Recording of LP Albums “Main Line to Panther” and Sounds of Steam Railroading” by A.R. -

PuffingBillyRailway SteamLocosService

Puffing Billy Railway ~ Steam Locos Service History Loco - Garratt NG127 Heritage Photo Current Photo © Puffing Billy Museum - Menzies Creek, Victoria, Australia - Aug 2017 1 Puffing Billy Railway ~ Steam Locos Service History Loco - Garratt NG127 Loco Description Former Built By Condition Location Photo Catlog Victorian Collections No Class & of No. 000016 Number NG127 G - Garratt NGG16 Beyer Awaiting Museum √ √ Date built - 1951 NG G16 127 Peacock, restoration Original owner - SAR 2-6-2+2-6-2 Manchester, Original gauge - builders England Withdrawn - No. 7428 VR Service History or other Service History SAR - South African Railways The Class NGG 16 2-6-2+2-6-2 Garratts were the final class of narrow gauge Garratts and were a direct descendant of the Class NGG 13 Garratts, such that the first batch were initially classified as Class NGG 13 locomotives. Three different builders built the Class NGG 16 locomotives in five batches. No. 85 to 88 were -

Derby Locomotive Drawings List.Xlsx

Derby Locomotive Drawing Lists Description: The collection consists of approximately 6000 drawings, plus 135 registers and lists. They cover the period from 1874 to 1961. The drawings relate to the construction, modification and rebuilding of locomotives of the Midland Railway, London Midland & Scottish Railway and British Railways, with occasional drawings from other railway companies and contractors. The drawings are mainly on linen with some blueprints, as well as Ozalid and paper copies. Each drawing has a number and/ or a letter code. These letter and number codes also relate to the registers, schedules and lists. The significance of these codes is explained in the ‘System of Arrangement’ section below. System of Arrangement: The drawings are arranged in the archive in five series and are listed as such in the catalogue. 1. Main Series. These are organised by drawing number in numerical sequence. Most drawings have a two number date prefix that usually relates to the year in which the drawing was produced, but may sometimes relate to the year the drawing was entered in the register. 2. D Numerical series. These are also organised by drawing number, but prefixed by the section reference, such as D1, D2, D3, D4 or D5. 3. Diagrams and Sketches. These are also organised by drawing number, but prefixed according to the section reference code, such as DS, DD, S, D or ED. 4. BR Standard Drawings from Derby. These drawings are proper to the main collection of British Rail Standard Drawings, but were found with the main Derby Works sequences. They are numerical with the prefix SL/DE. -

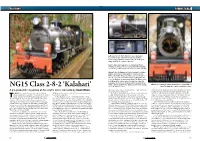

NG15 Class 2-8-2 'Kalahari'

REVIEWS 16MM SCALE Left: Accucraft UK’s NG15 ‘Kalahari.’ One of the largest locomotives to run on the Little Bovey and Heathfield Tramway. Ruggedly functional in her sober black livery. The damp conditions are evident in this shot. Top: The detail parts applied to the running boards. Just creeping into view are the dual safety valves. Whilst slightly over-size they look much better than the more usual offerings. Above: Under the dummy coal load is a manual feed water pump delivering via a similar ‘push in’ connector to that fitted on the boiler. The gas tank takes a modest amount of space in a generous water bath and you should just be able to see the dual gas injectors and feed pipe. The boiler return feed allows either excess water OR steam to pre-heat the feed-water. At the rear of the water bath is an empty space, which could take batteries for lighting, powered water pump Above: The ‘trademark’ opening smokebox door reveals dual fire NG15 Class 2-8-2 ‘Kalahari’ or a radio control receiver. tubes. The lamps are cosmetic mouldings, a shame. A pre-production inspection of Accucraft’s latest conducted by Stuart Moon. But it is a very nice model; and it has presence, looming large on slightly beyond the abilities of ‘open’ burner gas firing. Certainly it the steaming bay or station yard. would be possible to have made Kalahari internally coal or spirit- he NG15 2-8-2 tender loco is a classic design of South (WHR) fleet. Currently none of the three are running but one of But let us pass beyond the superficial matter of fiscal demand, fired with a multi-tube boiler complete with blowers, axial water African narrow gauge locomotive, the other being the NGG16 them is under restoration. -

The First Garratt Locomotive in the Netherlands

The first Garratt locomotive in the Netherlands By H. Brunner ME Translation ©2015 by René F. Vink, Netherlands In this article1 the reasons are mentioned that made the Limburg Tramway Co Ltd decide to purchase a "Garratt" locomotive. Furthermore a description is given of the acquired locomotive. General. In December 1931 a "Garratt" locomotive of 71.5 t [70.4 long ton] service weight was putinto service by the Limburg Tramway Co Ltd on her 26 km [16 mi] long line Maastricht-Vaals (fig. 1). Fig. 1. The Garratt locomotive In 1909 the Australian H.W. Garratt († 1913) obtained the patents on his engine type, with which the boiler was freely and completely accessible located on a frame that rested with pivots on a bogie each of which contained a separate locomotive engine. By locating the supply bunkers for water and coal on the bogie units, he diminished the tendency of the latter to rotate around their horizontal centers of gravitation at higher speeds as a consequence of the not fully counter balanced reciprocating masses of the components of the motion. Thus they contribute to the riding stability of the locomotive. He could increase the evaporative ability of the boiler almost at will because the dimensions of the boiler, the fire grate and the ash pan were no longer restricted by the tight dimensions and unfavourable restrictions of coupled wheels and water tanks. 1 This is a translation of the article that appeared in issue 35 of the Dutch magazine "De Ingenieur" (The Mechanical Engineer) in 1932. Some considerations apply to this translation - I followed the UK English spelling. -

STEAM TRAINS TODAY Riding the Heritage Railways of Britain

STEAM TRAINS TODAY Riding the Heritage Railways of Britain AndreW Martin PROFILE BOOKS Steam Trains Today.indd 3 18/02/2021 17:11 First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Profile Books Ltd 29 Cloth Fair London ec1a 7jq www.profilebooks.com Copyright © Andrew Martin, 2021 Extract from John Betjeman’s ‘Dilton Marsh’, from Collected Poems, by John Betjeman (John Murray Press, 1997, 4th edn.) reproduced with permission of John Murray Press 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Typeset in Berling Nova Text by MacGuru Ltd Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 1 78816 144 2 eISBN 978 1 78283 489 2 Steam Trains Today.indd 4 18/02/2021 17:11 Contents Some Terminology xi Preface Covid and the Heritage Lines xiii Introduction Mother’s Day at Loughborough 1 The Swapmeet 1 Along the Line 12 1: Railway Preservation Preserved or Heritage? 20 The Parallel Lines 25 Railway Preservation Before Beeching 30 Beeching Versus Betjeman 43 2: Some Pioneers The Talyllyn Railway 53 The Booming of the Mountain Wind 53 Volunteer Platelayers Required -

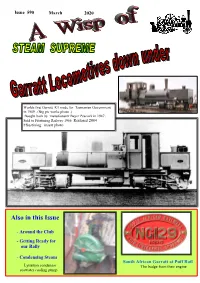

Also in This Issue

Issue 590 March 2020 Worlds first Garratt K1 made for Tasmanian Government in 1909 . (Big pic works photo .) Bought back by manufacturer Bayer Peacock in 1947 . Sold to Ffestiniog Railway 1966 Restored 2004 Ffrestiniog insert photo Also in this Issue - Around the Club - Getting Ready for our Rally - Condensing Steam South African Garratt at Puff Rail Lyttelton condensor The badge from their engine seawater cooling pump March 2020 Steam Supreme 2 NG 129 leaving Menzies Creek The recent recommissioning of Beyer Garratt NG129 by Puffing Billy Railway marks the completion of a long restoration process and provides a welcome boost to their locomotive fleet. By Avi Kulatunge and Peter Lynch Photos Avi Kulatumge and Tony Zaia NG129 is an articulated Garratt 2-6-2 +2-6-2 narrow gauge steam locomotive of the NG/G16 class built by Beyer Peacock & Co of Manchester in 1951. The Garratt design divides this 15 metre long locomotive into three sections, enabling it to negotiate sharper curves that a conventional rigid frame loco. The boiler and cab are supported by front and rear bogies, each of which has its own wheels and driving cylinders. A large water tank is mounted above the front wheels and a coal bunker on the rear section to distribute weight evenly. The Garratt locomotive design was devised by the British engineer Herbert Garratt during the early 1900s and patented by him in 1907, However Garratt died in 1913 and further development was carried out by Beyer, Peacock and Company, which acquired rights to the patent. The Beyer Garratt type was used throughout the world on both narrow and full sized railways. -

NSWGR AD60 NSWGR 4-8-4 + 4-8-4 Beyer Garratt Locomotive E168 Manufactured Exclusively for AR Kits by DJH Engineering from Patterns Owned by AR Kits & DJH

® Australian Railway Kits ABN: 27 416 246 418 Incorporating Main West Models Manufacturers, Wholesalers and Retailers of Quality Australian Model Railways PO Box 252 Warwick, Queensland, 4370 Australia Phone/Fax: 617 4667 1351 Website: www.arkits.com Email: [email protected] NSWGR AD60 NSWGR 4-8-4 + 4-8-4 Beyer Garratt Locomotive E168 Manufactured Exclusively for AR Kits by DJH Engineering from Patterns owned by AR Kits & DJH PLEASE READ INSTRUCTIONS THOROUGHLY BEFORE COMMENCING ASSEMBLY CONSTRUCTION It is important to ensure that all parts are clean, free of "flash" (excess metal on castings) and fit properly. The "flash line" is easily removed from most areas by scraping gently with a sharp hobby knife - a round blade is more effective than a straight pointed type. Pull the blade along the "flash line" - several light strokes are better than a single one. Some areas are better cleaned up with 6" jewellers' files. Take care not to flatten round parts by filing too heavily. All locating holes for detail fittings should be pre-drilled to the size specified in the instructions. Sometimes it is necessary to clean out these holes with a "rat tail" file; take care not to snap off the tip of the file. Gently wash the castings in warm soapy water to remove mould release residue. Etched brass items are best removed from the fret by placing the fret on a scrap piece of timber (e.g. Pyneboard) and cutting the tabs with a large Stanley knife - cut the tab at the point furthest away from the part, then trim the tab off close to the part with a small pair of quality side cutters.