A Memorial Essay for Henry Schwarzschild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T.Me/Booksandyou

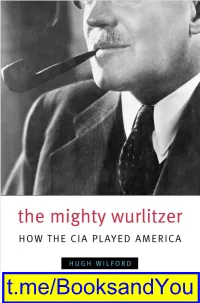

The Mighty Wurlitzer The Mighty Wurlitzer HOW THE CIA PLAYED AMERICA Hugh Wilford HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 2008 by Hugh Wilford All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2009. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wilford, Hugh, 1965– The mighty wurlitzer : how the CIA played America / Hugh Wilford. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-02681-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-674-03256-9 (pbk.) 1. United States. Central Intelligence Agency. 2. Intelligence service—United States. 3. Cold War. 4. Political culture—United States—History—20th century. 5. Public-private sector cooperation—United States—History—20th century. 6. United States—Politics and government—1945–1989. I. Title. JK468.I6W45 2008 327.1273009Ј045—dc22 2007021587 For Patty Contents List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Innocents’ Clubs: The Origins of the CIA Front 11 2 Secret Army: Émigrés 29 3 AFL-CIA: Labor 51 4 A Deep Sickness in New York: Intellectuals 70 5 The Cultural Cold War: Writers, Artists, Musicians, Filmmakers 99 6 The CIA on Campus: Students 123 7 The Truth Shall Make You Free: Women 149 8 Saving the World: Catholics 167 9 Into Africa: African Americans 197 10 Things Fall Apart: Journalists 225 Conclusion 249 Notes 257 Acknowledgments 319 Index 321 Illustrations Illustrations follow page 148. Allen Dulles Frank Wisner, 1934 A propaganda balloon release by the National Committee for a Free Europe George Meany and Jay Lovestone Sidney Hook, 1960 Arthur Koestler, Irving Brown, and James Burnham, 1950 Still from film adaptation of Orwell’s Animal Farm Henry Kissinger, 1957 U.S. -

The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America

The Mighty Wurlitzer The Mighty Wurlitzer HOW THE CIA PLAYED AMERICA Hugh Wilford HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 2008 by Hugh Wilford All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2009. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wilford, Hugh, 1965– The mighty wurlitzer : how the CIA played America / Hugh Wilford. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-02681-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-674-03256-9 (pbk.) 1. United States. Central Intelligence Agency. 2. Intelligence service—United States. 3. Cold War. 4. Political culture—United States—History—20th century. 5. Public-private sector cooperation—United States—History—20th century. 6. United States—Politics and government—1945–1989. I. Title. JK468.I6W45 2008 327.1273009Ј045—dc22 2007021587 For Patty Contents List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Innocents’ Clubs: The Origins of the CIA Front 11 2 Secret Army: Émigrés 29 3 AFL-CIA: Labor 51 4 A Deep Sickness in New York: Intellectuals 70 5 The Cultural Cold War: Writers, Artists, Musicians, Filmmakers 99 6 The CIA on Campus: Students 123 7 The Truth Shall Make You Free: Women 149 8 Saving the World: Catholics 167 9 Into Africa: African Americans 197 10 Things Fall Apart: Journalists 225 Conclusion 249 Notes 257 Acknowledgments 319 Index 321 Illustrations Illustrations follow page 148. Allen Dulles Frank Wisner, 1934 A propaganda balloon release by the National Committee for a Free Europe George Meany and Jay Lovestone Sidney Hook, 1960 Arthur Koestler, Irving Brown, and James Burnham, 1950 Still from film adaptation of Orwell’s Animal Farm Henry Kissinger, 1957 U.S. -

Department of Legal Studies University of Massachusetts-Amherst 110 Gordon Hall 418 N

THOMAS M. HILBINK Department of Legal Studies University of Massachusetts-Amherst 110 Gordon Hall 418 N. Pleasant Street, Suite C Amherst, MA 01002 413-545-2003 413-545-1640 (fax) [email protected] www.umass.edu/legal/Hilbink EDUCATION Ph.D. Candidate New York University Institute for Law & Society (A.B.D.) J.D. New York University School of Law (Magna Cum Laude), 1999 A.B. Columbia College (Columbia University), 1993 PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Assistant Professor, Department of Legal Studies, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, 2003 - present. Fellow/Lecturer, Law & Society Program, University of California-Santa Barbara, 2002-2003. Law Clerk, Judge Stephanie Seymour, United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, 2001-2002. Consulting Historian, American Civil Liberties Union National Legal Department, 2001. Fellow, Public Interest Law Center, NYU School of Law, 2001. Curriculum Developer, Education for Democracy Project, NYU School of Education, Summer 2000. Oral Historian, Supreme Court Historical Society Project on the Office of Solicitor General, Washington, D.C., Summer 2000. CEO and Co-Director, Democracy & Equality Project, Inc., Brooklyn, NY, 1999-2001. Intern, International Law Commission of the United Nations, Geneva, Switzerland, Summer 1998. Curriculum Developer, S.O.S. Racisme-Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, Summer 1997. Intern, Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson, Supreme Court of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, Summer 1996. Assistant to the President, American Civil Liberties Union, New York, NY, 1993-1995. Archivist, American Civil Liberties Union, New York, NY, 1991-1993. HONORS AND AWARDS 2001 J. Willard Hurst Legal History Fellow, University of Wisconsin 2001 Law & Society Association Graduate Student Workshop Grant 1999 Order of the Coif 1999 Law & Society Association Graduate Student Workshop Grant 1998 United Nations International Law Commission Fellow 1997 Robert McKay Scholar 1996-pres. -

Law School Announcements 1967-1968 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected]

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound University of Chicago Law School Announcements Law School Publications 9-30-1967 Law School Announcements 1967-1968 Law School Announcements Editors [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/ lawschoolannouncements Recommended Citation Editors, Law School Announcements, "Law School Announcements 1967-1968" (1967). University of Chicago Law School Announcements. Book 92. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/lawschoolannouncements/92 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Publications at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Law School Announcements by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago The Law School Announcements 1967-1968 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW SCHOOL Inquiries should be addressed as follows: Requests for information, materials, and application forms for admission and finan cial aid: For the J.D. Program: DEAN OF STUDENTS The Law School The University of Chicago I II I East ooth Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 2406 For the Graduate Programs: ASSISTANT DEAN (GRADUATE STUDIES) The Law School The University of Chicago I I I I East ooth Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 2433 Housing for Single Students: OFFICE OF STUDENT HOUSING The University of Chicago 580 I Ellis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 3149 Housing for Married Students: OFFICE OF MARRIED STUDENT HOUSING The University of Chicago 824 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone 752-3644 Payment of Fees and Deposits: THE BURSAR The University of Chicago 5801 Ellis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone MIdway 3-0800, Extension 3146 The University of Chicago Founded by John D. -

A Personal Meditation on Black-Jewish Relations

A Personal Meditation on Black-Jewish Relations A Talk Delivered at a joint program of Hendrix College and the University of Central Arkansas, sponsored by the Jewish Federation of Arkansas By Charney Vladeck Bromberg I was raised in a household where stories about the South and civil rights were part of the family lore. I was somewhere between thirteen and fourteen when the Little Rock school integration crisis happened, and later in that school year, when Minnijean Brown, one of the nine black students who so bravely integrated Central High was expelled, there was a rally in her support in Washington DC. I went, and I was lucky enough to ride in a school bus in which Minnijean led everyone in gospel and freedom songs. So, while I never put foot in Arkansas until yesterday, that experience, fifty years ago, rocked me to my core. By the early 1960’s, the civil rights movement was hitting home. I was growing up in Westchester County, New York – and in many of the most well-to- do villages and towns, as in so many places across America, Jews as well as blacks, could not buy homes because of restrictive covenants that were part of the housing title process. So, when I and two of my high school classmates decided to organize a youth group to help support the first of us who went South – a young woman who became the associate producer of Eyes on the Prize – we also undertook a campaign of passing out and collecting fair housing pledges in our own community. -

Furman Fundamentals Corinna Barrett Lain University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2007 Furman Fundamentals Corinna Barrett Lain University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Corinna Barrett Lain, Furman Fundamentals, 82 Wash L. Rev. 1 (2007) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright <C 2007 by Washington Law Review Association FURMAN FUNDAMENTALS Corinna Barrett Lain • For the first time in a long time, the Supreme Court's most important death penalty decisions all have gone the defendant's way. Is the Court's newfound willingness to protect capital defendants just a reflection of the times, or could it have come even without public support for those protections? At first glance, history allows for optimism. Furman v. Georgia, the 1972landmark decision that invalidated the death penalty, provides a seemingly perfect example of the Court's ability and inclination to protect capital defendants when no one else will. Furman looks countermajoritarian, scholars have claimed it was countermajoritarian, and even the Justices saw themselves as playing a heroic, countermajoritarian role in the case. But the lessons of Furman are not what they seem. Rather than proving the Supreme Court's ability to withstand majoritarian influences, Furman teaches the opposite-that even in its rnore countermajoritarian moments, the Court never strays far from dominant public opinion, tending instead to reflect the social and political movements of its time. -

Rabbi Philip Bentley for & the BDS Movement Murray Polner • Now Let Us Praise

Jewish Peace Letter Vol. 45 No. 3 Published by the Jewish Peace Fellowship April 2016 Time Bombs Carol Ascher • One State Ahead? Peter Dreier • Israel’s New McCarthyism & Stefan Merken • Rabbi Philip Bentley FOR & the BDS Movement Murray Polner • Now Let Us Praise . ISSN: 0197-9115 From Where I Sit Stefan Merken Occasionally We Have Disagreements... ften we share space and time with those with BDS movement is not the correct way to bring about change. whom we share some commonality. Either our kids The FOR National Council recently passed a resolution in are the same age, our political leanings are similar, support of BDS. No one on the JPF Board was consulted or Oor our value systems are in sync. Whatever it is, we seem to asked to offer an opinion on the issue. Finally, after much be drawn together. But occasionally we have disagreements. debate and conversation, FOR’s National Council adopted its For years, the Jewish Peace Fellowship office has been resolution. When I learned of this, I wrote to the FOR and housed in the building that Fellowship of Reconciliation informed them that the JPF could not and would not stand (FOR) owns in Nyack. Rabbi Michael Robinson lived across with them in support of this resolution. We are opposed to the river from Nyack and felt that we were similar organiza- BDS. tions and it would be “right” to rent a small office from the What followed was a friendly but frank conversation be- FOR and be close. We have been together ever since. tween Rabbi Phil Bentley (for the JPF) and members of the Over the past two years FOR’s National Council has FOR’s National Council and staff. -

Arendt on Arendt: Reflecting on the Meaning of the Eichmann Controversy Audrey P

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2015 Arendt on Arendt: Reflecting on the Meaning of the Eichmann Controversy Audrey P. Jaquiss Pomona College Recommended Citation Jaquiss, Audrey P., "Arendt on Arendt: Reflecting on the Meaning of the Eichmann Controversy" (2015). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 135. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/135 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Eichmann Controversy: The American Jewish Response to Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts at Pomona College Department of History By Audrey Jaquiss April 17, 2015 Acknowledgements A writer is nothing without her readers. I would like to thank Professor Pey-Yi Chu for her endless support, brilliant mind and challenging pedagogy. This thesis would not be possible without her immense capacity for both kindness and wisdom. I would also like to thank Professor John Seery for his inspiring conversation and for all the laughter he shared with me along the way. This thesis would not be possible without the curiosity and ceaseless joy he has helped me find in my work. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..2 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..5 1. Building a Memory Through Controversy……………………………………………25 1. The Stakes of a Memory ……………………………………………………...33 2. The Banality of Evil…………………………………………………...............41 3. -

Interpretations of the Crown Heights Riot 97

E.S. Shapiro: Interpretations of the Crown Heights Riot 97 Interpretations of the Crown Heights Riot EDWARD S. SHAPIRO* The Crown Heights riot of August 1991 was one of the most serious incidents of antisemitism in American history. It took place in the Crown Heights neighborhood of Brooklyn, the worldwide center of the Lubavitch Hasidic movement, and lasted for three days. The riot was precipitated by an automobile accident involving a motorcade carrying the Lubavitcher rebbe back from one of his periodic trips to the Lubavitch cemetery in the borough of Queens. The accident killed a young boy named Gavin Cato and injured his cousin Angelina. The riot terrorized and trauma- tized the 20,000 Lubavitchers of Crown Heights. Yankel Rosenbaum, a Lubavitcher from Australia living temporarily in Crown Heights, was murdered; Bracha Estrin, a Lubavitch survivor of the Holocaust, com- mitted suicide; six stores were looted; 152 police officers and 38 civilians claimed to have been injured; 27 police vehicles were damaged or destroyed; and 129 persons were arrested.1 While the property damage and the number of killed and injured were small compared to other riots in American history, they did not appear so to contemporaries. The extensive attention the riot received was due in part to the fact that it occurred in the media center of America, if not of the world. The riot was preceded by two other events in 1991 which, along with the riot, seemed to indicate that the liberal political alliance between blacks and Jews was unraveling and that a new chapter in the history of black-Jewish relations and of New York City had opened. -

Jewish Lawyers and the Long Civil Rights Movement 1933-1965: Race, Rights and Representation

Jewish Lawyers and the Long Civil Rights Movement 1933-1965: Race, Rights and Representation Linda Ann Albin Submitted for the degree of Master of Arts by Research University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies June 2018 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived therefrom must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 1 Word Count: 36,652. (Excluding appendices) 2 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................5 ABSTRACT ..........................................................................................................................6 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................7 Jewish Lawyers and American Civil Rights History 1933-1965 ..............................................7 Jewish Lawyers and the Long Civil Rights Movement .............................................................8 CHAPTER ONE: Jewish Civil Rights Lawyers: Who They Were and Where They Came From .........................................................................................................................18 The New Dealers .........................................................................................................................23 -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 21, Number 35, September

Join the Schiller Institute! Every renaissance in history has been associated "Whoever would overthrow the liberty of a nation with the written word, from the Greeks, to the must begin by subduing the freeness of speech." Arabs, to the great Italian 'Golden Renaissance.' NeW Federalist is devoted to keeping that "freeness." The Schiller Institute, devoted to creating a new Golden Renaissance from the depths of the current Join the Schiller Institute and receive NEW Dark Age, offers a year's subscription to two prime FEDERALIST and FIDELIO as part of the publications-Fidelio and New Federalist, to new membership: members: • $1,000 Lifetime Membership Fidelio is a quarterly journal of poetry, science and • $500 Sustaining Membership statecraft, which takes its name from Beethoven's • $100 Regular Annual Membership great operatic tribute to freedom and republican All these memberships include: virtue. New Federalist is the national newspaper of the .4 issues FIDELIO ($20 value) American System. As Benjamin Franklin said, .100 issues NEW FEDERALIST ($35 value) ------------------------- clip and send ------------------------- this coupon with your check or money order to: Schiller Institute, Inc. P.o. Box 66082, Washington, D.C. 20035-6082 Sign me up as a member of the Schiller Institute. ___ Name _________________________________ ____ D $1,000 Lifetime Membership o $ 500 Sustaining Membership Address _______________________________________ o $ 100 Regular Annual Membership __ _______ City _____________________________ __ o $ 35 Introductory Membership (50 issues NEW FEDERALIST only) State ______ Zip ________ Phone ( Founder and Contributing Editor: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. Editor: Nora Hamerman Managing Editors: John Sigerson, Susan Welsh From the Editor Assistant Managing Editor: Ronald Kokinda Editorial Board: Warren Hamerman, Melvin Klenetsky, Antony Papert, Gerald Rose, Edward Spannaus, Nancy Spannaus, Webster Tarpley, he result of the Aug. -

SENTENCING. 'In CAPITAL CASES HEARING

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. SENTENCING. 'iN CAPITAL CASES HEARING (' BEFORE THE I SUBCOM.MITTEE ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE ,. IV· OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES NINETY-FIFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 13360 SENTENOING TN CAPITAL CASES ) JULY 19, 1978 , Serial No. 74 l .. t I 11 0--- :I- I I. : . ()Q~. ~~ .. for the u,. of the Committee on the Judicia", . ~~ •.. U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE .lr) ~ · WASHINGTON, 1978 • I. " COMMI.TTEE ON THE JUDICIARY PETER W. RODINO, JII., New Jersey, Chair1ltal~ .TACK BROOKS, Texas ROBERT McCLORY, Illinois ROBERT W. KARTENi\IEIER, Wisconsin TOU RAILSBACK, Ililnols DON EDWARDS, California CHAf(t,ES E. WIGGINS, California JOHN CONYERS, JII., i\Ilchlgan HAMILTON FISH, JII., New York JOSHUA EILBERG, Pennsylvania 111. CALDWELL BUTLER, Virglnln WALTER FLOWERS, Alp.1l11ma WILLIAM S. COHEN, i\Inlne JA1IIElS R.MANN, South Carolinll CARLOS J. MOORHEAD, California JOHN F. SEIBERLING, Ohio JOHN M. ASHBROOK, Ohio GEORGE E. DANIELSON, California HENRY J. HYDE, 111\nols ROBERT F. DRINAN, Massachusetts THOMAS N. KINDNESS, Ohio BARBARA JORDAN, Texas HAROLD S. SAWYER,Mlchlgan ELIZABETH HOLTZMAN, New York ROMANO L. MAZZOLI, Kentucky WILLIAM J. HUGHES, New Jersey SAM B. HALL, JR., Texas I,AMAR GUDGER, North Carollnn HAROLD L. VOLK1\IElR, Missouri HERBERT E. HARRIS II, Vlrglnln JIM SANTINI, Nevada ALLEN E. ER':i'EL, Pennsylvania BILLY LEE EVANS, Georgia ANTHONY C. BE1LENSON, California ALAN A. PARKER, General CounBel GARNER J. CLINE, Stat! Director FRANKLIN G. POLK, ABsociate CounBel SUBCOMMITTEE ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE JAMES R. MANN, South Carolina, Chairman ELIZABETH HOLTZMAN, New York CHARLES E.