T.Me/Booksandyou

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Victor G. Reuther Papers LP000002BVGR

*XLGHWRWKH9LFWRU*5HXWKHU3DSHUV /3B9*5 7KLVILQGLQJDLGZDVSURGXFHGXVLQJ$UFKLYHV6SDFHRQ0DUFK (QJOLVK 'HVFULELQJ$UFKLYHV$&RQWHQW6WDQGDUG :DOWHU35HXWKHU/LEUDU\ &DVV$YHQXH 'HWURLW0, 85/KWWSVUHXWKHUZD\QHHGX Guide to the Victor G. Reuther Papers LP000002_VGR Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 History ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 8 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 9 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Series I: Reuther Brothers, -

2018 Autumn (PDF)

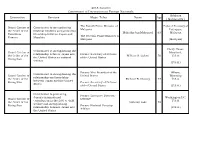

2018 Autumn Conferment of Decoration on Foreign Nationals Address Decoration Services Major Titles Name Age ( Nationality ) The Fourth Prime Minister of Federal Territory of Grand Cordon of Contributed to strengthening Malaysia Putrajaya, the Order of the bilateral relations and promoting Mahathir bin Mohamad 93 Malaysia Paulownia friendship between Japan and The Seventh Prime Minister of Flowers Mayalsia Malaysia (Malaysia) Chevy Chase, Contributed to strengthening the Grand Cordon of Maryland, relationship between Japan and Former Secretary of Defense the Order of the William S. Cohen 78 U.S.A. the United States on national of the United States Rising Sun defense (U.S.A.) Former Vice President of the Wilson, Contributed to strengthening the Grand Cordon of United States Wyoming relationship and friendship the Order of the Richard B. Cheney 77 U.S.A. between Japan and the United Rising Sun Former Secretary of Defense States of the United States (U.S.A.) Contributed to promoting Former Executive Director, Japan's international Washington DC, Grand Cordon of UNICEF contribution in the field of child U.S.A. the Order of the Anthony Lake 79 welfare and strengthening Rising Sun Former National Security relationship between Japan and (U.S.A.) Advisor the United States 2018 Autumn Conferment of Decoration on Foreign Nationals Former Vice Prime Minister Hydra, Contributed to strengthening Former Minister of Interior Grand Cordon of Alger, bilateral relations and promoting and Local Governments the Order of the Noureddine Yazid Zerhouni 81 Algeria -

The Freeman June 1954

JUNE 28~ 1954 The Union Member: America's Laziest Man By Victor Riesel The Debacle of the Fabians By Russell Kirk Articles and Book Reviews by Max Eastman, Norbert Muhlen, James Burnham, Joseph Wood~ Krutch, Robert Cantwell, Eugene Lyons, Argus, William F. Buckley, Jr. New Rod Mill at J&L's AI"Iqulppa. Works THE A Fortnightly Among Ourselves For With the publication in 1953 of The Conserva ti've Mind, RUSSELL KIRK became nationally re reeman Individualists cognized as one of the foremost young leaders of conservative thought in the country. He enjoys an equal reputation in England, hav Executive Director KURT LASSEN ing contributed frequently to British journals Managing Editor FLORENCE NORTON and taken his doctor's degree at Scotland's famous old St. Andrews University. Because of his personal acquaintance with the British political and intellectual scene, Mr. Kirk has a more than academic interest in the New Contents VOL. 4, NO. 20 JUNE 28, 1954 Fabianism, which he analyzes in this issue (p. 695). At present Mr. Kirk is finishing a new book, A Program for Conserpatives, Editor~als to be published by the Henry Regnery Company. At luncheon not long ago we asked VICTOR 'The Fortnight .. 0•0•00000•00 •••••• 0 0 ••••• 0 0 0 •• 0 0 0 o. 689 RIESEL for his explanation of the general How Not to Run a Party . 0 •••••••••••• 0 •••••••••• 0 •• 691 apathy we had noticed among most of the The Oppenheimer Finding 692 members of labor unions with whom we had In Freedom's Calendar 693 any acquaintance. His answer (p. -

Kennethj. Heineman Ohio University-Lancaster

REFORMATION: MONSIGNOR CHARLES OWEN RICE AND THE FRAGMENTATION OF THE NEW DEAL ELECTORAL COALITION IN PITTSBURGH, 1960-1972 Kennethj. Heineman Ohio University-Lancaster he tearing apart of the New Deal electoral coalition in the i96os has attracted growing scholarly and media attention. Gregory Schneider and Rebecca Klatch emphasized the role collegiate lib- ertarians played in moving youths to the Right. Rick Perlstein, focusing on conservatives who came of age during World War II, argued that the New Right wedded southern white racism to midwestern conspiracy-obsessed anti-Communism. For his part, Dan Carter contended that Alabama governor George Wallace's racist politics migrated north where they found a receptive audi- ence in urban Catholics.' Samuel Freedman chronicled the ideological evolution of sev- eral generations of northern Catholics as they moved into the GOP in reaction to black protest, mounting urban crime, and the Vietnam War. Ronald Formisano, Jonathan Rieder, and Thomas Sugrue, in their studies of Boston, New York, and Detroit, respectively, gave less attention to the Vietnam War, emphasizing the racial attitudes of working-class Catholics and unionists. In PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY: A JOURNAL OF MID-ATLANTIC STUDIES, VOL. 7 1, NO. I, 2004. Copyright © 2004 The Pennsylvania Historical Association PENNSYLVANIA HISTORY their surveys of the relationship between Catholics and blacks, John McGreevy and Gerald Gamm argued that urban Catholics frequently did not respond well to blacks. 2 Ronald Radosh and Steven Gillon took a different tack from Carter, Gamm, and Sugrue. In their studies of the Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), an organization that anti-Communist Democrats such as Minneapolis mayor Hubert Humphrey had helped create in I947, Radosh and Gillon examined the middle-class activists who rejected America's anti-Communist foreign policy and the racial conservatism of many unionists. -

ANTA Theater and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission August 6, 1985; Designation List 182 l.P-1309 ANTA THFATER (originally Guild Theater, noN Virginia Theater), 243-259 West 52nd Street, Manhattan. Built 1924-25; architects, Crane & Franzheim. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1024, Lot 7. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the ANTA Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty-three witnesses spoke in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The ANTA Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built in the 1924-25, the ANTA was constructed for the Theater Guild as a subscription playhouse, named the Guild Theater. The fourrling Guild members, including actors, playwrights, designers, attorneys and bankers, formed the Theater Guild to present high quality plays which they believed would be artistically superior to the current offerings of the commercial Broadway houses. More than just an auditorium, however, the Guild Theater was designed to be a theater resource center, with classrooms, studios, and a library. The theater also included the rrost up-to-date staging technology. -

Uvfuv 90.7 F M New York

FORDHAM UNIVERSITY BRONX, NEW YORK 10458 (212) 933-2233 EXT. 243-244 uvfuv 90.7 f m new york May 7th, 1973 160 West 73d St. New York City 10023 Miss Jane Becker Publicity Manager ALFRED A. KNOPF INC. 201 East 50th St. New York City Dear Miss Becker: I note that the publication date for Artur Rubinstein's new book is near. I thought I would send you this £ote in regard to my broadcasts^ in the even something might be worked out. As the enclosed indicates—I am a concert pianist, having been a scholarship student at the Juilliard with the late Olga Samaroff- Stokowsky, and also having spent a summer with Josef Hofmann. My radio show----- "BERNARD GABRIEL VIEWS THE MUSIC SCENE" has been on the air nearly 7 years now-.....- and I interview such musical figures as: YEHUDI MENUHIN, SIR RUDOLF BING, ERICA MORINI, LILI KRAUS, LEON BARZIN, THOMAS SCHERMAN, EARL WILD, WILLIAM MASSELOS, JOHN STEINWAY etc. etc. I mention the above-------because, I imagine Artur Rubinstein might be tempted to do an interview, since I am a professional musician —and might not just do the usual generalized type of chat with him. My broadcasts are heard by a great many radio stations coast to coast-------via "NATIONAL PUBLIC RADIO", and are heard independently over WFUV in NYC every Monday night---------- 9-9:30PM. I should greatly like to talk with Mr. Rubinstein-------but in any everiTwould like to review the book.(l di a great many book reviews on the show, and talk with a variety of authors.) Possibly you would show Mr. -

Commentary Strictly Onfidential Heard in the Lobbies You and Me

Page Two -THE JEWISH. NEWS Friday, April 6, •1945 Purely My Host: The Jewish Brigade Between , By JOHN FREDERICK Commentary EDITOR'S NOTE: John Frederick, screen and stage actor now on tour entertaining the U. S. forces in Europe, started his career in Hollywood under Jesse Lasky, and was recently You and Me By PHILIP SLOMOVITZ featured in a Guy Named Joe, Song of Russia, and other pictures. His report on the Jewish Brigade, probably the first by a Gentile, was contained in a letter he wrote a friend. By BORIS SMOLAR HARVARD'S JEWISH QUOTAS SOMEWHERE IN ITALY—I have just come from a most awe-inspiring (Copyright, 1945, Jewish Telegraphic A legislative committee. in Massachu- three-day leave in a little village high in the mountains of liberated Italy, Agency, Inc.) setts was told last week, by Prof. Albert where I had the rare privilege of being present at a unique and unprece- SAN FRANCISCO SIDELIGHTS Sprague Coolidge, that Harvard Univer- dented development of history. sity makes it a point not to award schol- At the outbreak of war, when Palestine Jes,vry's demand - for -a Jewish Zionist leaders in America are becom- arships to Jews and that "we know per- army was refused by . the :English, 20,000 Palestine Jews enlisted in the ing more and more certain that while no British Army. In 1944, Prime Minister Churchill, at long last, announced the fectly well that names ending in 'berg' other Jewish groups will have a chance creation of a complete Jewish Infantry Brigade to serve in combat, flying of even coming close to the United Na- and 'stein' have to be skipped by the their own flag and under Jeivish command. -

Trauma and Recovery in Children's Books About Natural Disasters

VOL. 50, NO.1 JANUARY 2012 FEATURED ARTICLES Surviving the Storm: Trauma and Recovery in Children’s Books about Natural Disasters • Pathways’ End: The Space of Trauma in Patrick Ness’s Chaos Walking • Hearing the Voices of “Comfort Women”: Confronting Historical Trauma in Korean Children’s Literature • Representations of Trauma and Recovery in Contemporary North American and Australian Teen Fiction • Resistant Rituals: Self-Mutilation and the Female Adolescent Body in Fairy Tales and Young Adult Fiction • Death Row Everyman: Stanislas Gros’s Image-Based Interpretation of Victor Hugo’s The Last Day of a Condemned Man Would you like to write for IBBY’s journal? Academic Articles ca. 4000 words The Journal of IBBY, the International Board on Books for Young People Bookbird publishes articles on children’s literature with an international perspective four times a year Copyright © 2012 by Bookbird, Inc. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the (in January, April, July and October). Articles that compare literatures of different countries are of interest, editors. as are papers on translation studies and articles that discuss the reception of work from one country in Editors: Roxanne Harde, University of Alberta—Augustana Faculty (Canada) and Lydia Kokkola, University of Turku another. Articles concerned with a particular national literature or a particular book or writer may also be (Finland) suitable, but it is important that the article should be of interest to an international audience. Some issues are devoted to special topics. Details and deadlines of these issues are available from Bookbird’s web pages. Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Augustana Faculty at the University of Alberta, Camrose, Alberta, Canada. -

The Unmaking of an American

Volume 17 | Issue 4 | Number 5 | Article ID 5253 | Feb 15, 2019 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Unmaking of an American Roger Pulvers On 15 March, Balestier Press brings out Roger “The Unmaking of an American” is a cross- Pulvers’ autobiography, “The Unmaking of an cultural memoir spanning decades of dramatic American.” history on four continents. The excerpts from the book below present a wide-ranging This book is an exploration of the nature of introduction to the range of Japanese memory and how it links us with people from contemporary cosmopolitan culture and moral different places and distant times. It ranges issues confronting Japan and the United States from Roger’s upbringing in a Jewish household at war from the Asia-Pacific War to the Vietnam in Los Angeles to his first trip abroad, in 1964, War, from war crimes tribunals of Japanese to the Soviet Union; from his days at Harvard generals to the firebombing and atomic Graduate School studying Russian to his stay in bombing of Japan, to the Vietnam War. They Warsaw, a stay that was truncated by a spy include introducing the author’s interactions scandal that rocked the United States; from his with leading Japanese filmmakers, playwrights arrival in Kyoto in 1967 to his years in and authors, among others: Oshima Nagisa Australia, where, in 1976, he gave up his (Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence) and Shinoda American citizenship for an Australian one. Masahiro (Spy Sorge on Comintern espionage in China), playwright Kinoshita Junji (author of a play on the Sorge affair), and Koizumi Takashi (Best Wishes for Tomorrow). -

Spring / Summer 2020 Contents Support the Press

Spring / Summer 2020 Contents Support the Press General Interest 1 Help the University of Nebraska Press continue its New in Paperback/Trade 46 vibrant program of publishing scholarly and regional Scholarly Books 64 books by becoming a Friend of the Press. Distribution 95 To join, visit nebraskapress.unl.edu or contact New in Paperback/Scholarly 96 Erika Kuebler Rippeteau, grants and development Selected Backlist 100 specialist, at 402-472-1660 or [email protected]. Journals 102 To find out how you can help support a particular Index 103 book or series, contact Donna Shear, Press director, at Ordering Information 104 402-472-2861 or [email protected]. Ebooks available for each title unless otherwise indicated. Subject Guide Africa 14, 30–32, 66, 78 History/American 2, 9, 13, 17–18, 20, Native American & Indigenous Studies 34–38, 48–50, 55–58, 63, 65, 68, 70, 15, 39, 52–55, 71, 80, 82–84, 86–87, African American Studies 14, 16, 50, 80–81, 84–87, 96–99 95–98 78, 99 History/American West 11–12, 25, 38, Natural History 37, 54 American Studies 73–75 54, 57, 59, 73, 95 Philosophy 40, 88 Anthropology 79, 83, 85–87 History/World 7, 18, 61, 68–70, 88, Poetry 14, 29–33, 41, 54, 56 Art & Photograph 7, 83 92–94 Political Science 4, 8, 11, 13, 24, 66, 85, Jewish History & Culture 35, 40–44 Asia 6–7, 17, 47 99 Bible Studies 43–44 Journalism 8, 20, 57, 65 Religion 39–41, 43–44, 88, 94 Biography 1, 8–9, 18, 23, 25, 36, 47, 56, Law/Legal Studies 4, 57, 70 Spain 90, 92–94 59, 62 Literature & Criticism 10, 32, 41, 44, Sports 1–3, 16–19, 34–35, 46–51, 65 -

The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America

The Mighty Wurlitzer The Mighty Wurlitzer HOW THE CIA PLAYED AMERICA Hugh Wilford HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 2008 by Hugh Wilford All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2009. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wilford, Hugh, 1965– The mighty wurlitzer : how the CIA played America / Hugh Wilford. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-674-02681-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-674-03256-9 (pbk.) 1. United States. Central Intelligence Agency. 2. Intelligence service—United States. 3. Cold War. 4. Political culture—United States—History—20th century. 5. Public-private sector cooperation—United States—History—20th century. 6. United States—Politics and government—1945–1989. I. Title. JK468.I6W45 2008 327.1273009Ј045—dc22 2007021587 For Patty Contents List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Innocents’ Clubs: The Origins of the CIA Front 11 2 Secret Army: Émigrés 29 3 AFL-CIA: Labor 51 4 A Deep Sickness in New York: Intellectuals 70 5 The Cultural Cold War: Writers, Artists, Musicians, Filmmakers 99 6 The CIA on Campus: Students 123 7 The Truth Shall Make You Free: Women 149 8 Saving the World: Catholics 167 9 Into Africa: African Americans 197 10 Things Fall Apart: Journalists 225 Conclusion 249 Notes 257 Acknowledgments 319 Index 321 Illustrations Illustrations follow page 148. Allen Dulles Frank Wisner, 1934 A propaganda balloon release by the National Committee for a Free Europe George Meany and Jay Lovestone Sidney Hook, 1960 Arthur Koestler, Irving Brown, and James Burnham, 1950 Still from film adaptation of Orwell’s Animal Farm Henry Kissinger, 1957 U.S. -

Department of Legal Studies University of Massachusetts-Amherst 110 Gordon Hall 418 N

THOMAS M. HILBINK Department of Legal Studies University of Massachusetts-Amherst 110 Gordon Hall 418 N. Pleasant Street, Suite C Amherst, MA 01002 413-545-2003 413-545-1640 (fax) [email protected] www.umass.edu/legal/Hilbink EDUCATION Ph.D. Candidate New York University Institute for Law & Society (A.B.D.) J.D. New York University School of Law (Magna Cum Laude), 1999 A.B. Columbia College (Columbia University), 1993 PROFESSIONAL POSITIONS Assistant Professor, Department of Legal Studies, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, 2003 - present. Fellow/Lecturer, Law & Society Program, University of California-Santa Barbara, 2002-2003. Law Clerk, Judge Stephanie Seymour, United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, 2001-2002. Consulting Historian, American Civil Liberties Union National Legal Department, 2001. Fellow, Public Interest Law Center, NYU School of Law, 2001. Curriculum Developer, Education for Democracy Project, NYU School of Education, Summer 2000. Oral Historian, Supreme Court Historical Society Project on the Office of Solicitor General, Washington, D.C., Summer 2000. CEO and Co-Director, Democracy & Equality Project, Inc., Brooklyn, NY, 1999-2001. Intern, International Law Commission of the United Nations, Geneva, Switzerland, Summer 1998. Curriculum Developer, S.O.S. Racisme-Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, Summer 1997. Intern, Chief Justice Shirley Abrahamson, Supreme Court of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, Summer 1996. Assistant to the President, American Civil Liberties Union, New York, NY, 1993-1995. Archivist, American Civil Liberties Union, New York, NY, 1991-1993. HONORS AND AWARDS 2001 J. Willard Hurst Legal History Fellow, University of Wisconsin 2001 Law & Society Association Graduate Student Workshop Grant 1999 Order of the Coif 1999 Law & Society Association Graduate Student Workshop Grant 1998 United Nations International Law Commission Fellow 1997 Robert McKay Scholar 1996-pres.