The Welfare of Animals Used in Entertainment Lecture Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

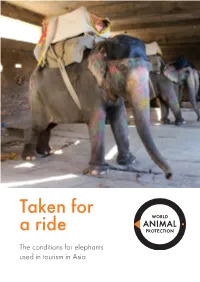

Taken for a Ride

Taken for a ride The conditions for elephants used in tourism in Asia Author Dr Jan Schmidt-Burbach graduated in veterinary medicine in Germany and completed a PhD on diagnosing health issues in Asian elephants. He has worked as a wild animal veterinarian, project manager and wildlife researcher in Asia for more than 10 years. Dr Schmidt-Burbach has published several scientific papers on the exploitation of wild animals as part of the illegal wildlife trade and conducted a 2010 study on wildlife entertainment in Thailand. He speaks at many expert forums about the urgent need to address the suffering of wild animals in captivity. Acknowledgment This report has only been possible with the invaluable help of those who have participated in the fieldwork, given advice and feedback. Thanks particularly to: Dr Jennifer Ford, Lindsay Hartley-Backhouse, Soham Mukherjee, Manoj Gautam, Tim Gorski, Dananjaya Karunaratna, Delphine Ronfot, Julie Middelkoop and Dr Neil D’Cruze. World Animal Protection is grateful for the generous support from TUI Care Foundation and The Intrepid Foundation, which made this report possible. Preface Contents World Animal Protection has been moving the world to protect animals for more than 50 years. Currently working in over Executive summary 6 50 countries and on 6 continents, it is a truly global organisation. Protecting the world’s wildlife from exploitation and cruelty is central to its work. Introduction 8 The Wildlife - not entertainers campaign aims to end the suffering of hundreds of thousands of wild animals used and abused Background information 10 in the tourism entertainment industry. The strength of the campaign is in building a movement to protect wildlife. -

The State of the Animals II: 2003

A Strategic Review of International 1CHAPTER Animal Protection Paul G. Irwin Introduction he level of animal protection Prior to the modern period of ani- activity varies substantially Early Activities mal protection (starting after World Taround the world. To some War II), international animal protec- extent, the variation parallels the in International tion involved mostly uncoordinated level of economic development, as support from the larger societies and countries with high per capita Animal certain wealthy individuals and a vari- incomes and democratic political Protection ety of international meetings where structures have better financed and Organized animal protection began in animal protection advocates gathered better developed animal protection England in the early 1800s and together to exchange news and ideas. organizations. However there is not spread from there to the rest of the One of the earliest such meetings a one-to-one correlation between world. Henry Bergh (who founded the occurred in Paris in June 1900 economic development and animal American Society for the Prevention although, by this time, there was protection activity. Japan and Saudi of Cruelty to Animals, or ASPCA, in already a steady exchange of informa- Arabia, for example, have high per 1865) and George Angell (who found- tion among animal protection organi- capita incomes but low or nonexis- ed the Massachusetts Society for the zations around the world. These tent levels of animal protection activ- Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, or exchanges were encouraged further ity, while India has a relatively low per MSPCA, in 1868) both looked to by the organization of a number of capita income but a fairly large num- England and the Royal Society for the international animal protection con- ber of animal protection groups. -

Taken for a Ride Report

Taken for a ride The conditions for elephants used in tourism in Asia Preface We have been moving the world to protect animals for more than 50 years. Currently working in more than 50 countries and on six continents, we are a truly global organisation. Protecting the world’s wildlife from exploitation and cruelty is central to our work. The Wildlife – not entertainers campaign aims to end the suffering of hundreds of thousands of wild animals used and abused in the tourism entertainment industry. The strength of the campaign is in building a movement to protect wildlife. Travel companies and tourists are at the forefront of taking action for elephants, and other wild animals. Moving the travel industry In 2010 TUI Nederland became the first tour operator to stop all sales and promotion of venues offering elephant rides and shows. It was soon followed by several other operators including Intrepid Travel who, in 2013, was first to stop such sales and promotions globally. By early 2017, more than 160 travel companies had made similar commitments and now offer elephant-friendly tourism activities. TripAdvisor announced in 2016 that it would end the sale of tickets for wildlife experiences where tourists come into direct contact with captive wild animals, including elephant riding. This decision was in response to 550,000 people taking action with us to demand that the company stop profiting from the world’s cruellest wildlife attractions. Yet these changes are only the start. There is much more to be done to save elephants and other wild animals from suffering in the name of entertainment. -

A Strategic Review of International Animal Protection

A Strategic Review of International 1CHAPTER Animal Protection Paul G. Irwin Introduction he level of animal protection Prior to the modern period of ani- activity varies substantially Early Activities mal protection (starting after World Taround the world. To some War II), international animal protec- extent, the variation parallels the in International tion involved mostly uncoordinated level of economic development, as support from the larger societies and countries with high per capita Animal certain wealthy individuals and a vari- incomes and democratic political Protection ety of international meetings where structures have better financed and Organized animal protection began in animal protection advocates gathered better developed animal protection England in the early 1800s and together to exchange news and ideas. organizations. However there is not spread from there to the rest of the One of the earliest such meetings a one-to-one correlation between world. Henry Bergh (who founded the occurred in Paris in June 1900 economic development and animal American Society for the Prevention although, by this time, there was protection activity. Japan and Saudi of Cruelty to Animals, or ASPCA, in already a steady exchange of informa- Arabia, for example, have high per 1865) and George Angell (who found- tion among animal protection organi- capita incomes but low or nonexis- ed the Massachusetts Society for the zations around the world. These tent levels of animal protection activ- Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, or exchanges were encouraged further ity, while India has a relatively low per MSPCA, in 1868) both looked to by the organization of a number of capita income but a fairly large num- England and the Royal Society for the international animal protection con- ber of animal protection groups. -

Tracking the Travel Industry Which Companies Are Checking out of Wildlife Cruelty?

Tracking the travel industry Which companies are checking out of wildlife cruelty? Contents World Animal Protection is registered with the Charity Foreword 3 Commission as a charity and Executive summary 4 with Companies House as a company limited by Why protecting wildlife in tourism matters 6 guarantee. World Animal Protection is governed by its Methodology 9 Articles of Association. Company selection 9 Charity registration number Company ranking 10 1081849 Company registration number 4029540 Results 13 Overall ranking 13 Registered office 222 Gray’s Inn Road, London WC1X Section 1 – Commitment 14 8HB Section 2 – Targets and performance 18 Section 3 – Changing industry supply 19 Section 4 – Changing consumer demand 21 Conclusion 22 Recommendations 24 Appendix 1 – 10 steps to become wildlife-friendly 26 Appendix 2 – How to draft an animal welfare policy 27 Appendix 3 – Ready-to-go animal welfare policy template 31 Appendix 4 Individual company report summaries and selection rationale for 2020 33 4.1. Airbnb 34 4.2 AttractionTickets.com 36 4.3 Booking.com 38 4.4 DER Touristik 40 4.5 Expedia 42 4.6 Flight Centre 44 4.7 GetYourGuide 46 4.8 Klook 48 4.9 Musement 50 4.10 The Travel Corporation 52 4.11 Trip.com 54 4.12 Tripadvisor 56 4.13 TUI.co.uk 58 4.14 Viator 60 References 62 Cover image: In principle, observing dolphins in the wild is more responsible than observing them in captivity – if managed and implemented responsibly and appropriately. In the wild, dolphins are completely free, live in their natural habitat, and can undertake all of their natural behaviours, such as hunting, foraging, resting, playing and travelling. -

In Recent Years, Animal Attractions Have Become Increasingly Common Within Tourism Destinations

In recent years, animal attractions have become increasingly common within tourism destinations. Seeing wild animals when travelling is a memorable part of any travel experience and when done responsibly these encounters can play a major role in protecting wildlife and their natural habitats. Unfortunately, there are certain practices that have a known detrimental welfare impact or are wholly exploitative to animals. As a result up to half a million wild animals suffer to entertain tourist around the world. Animals at these wildlife attractions are either taken from the wild or bred in captivity so tourists can swim with a dolphin, take a tiger selfie, walk with lions, ride or wash an elephant or be offered animal souvenirs or by-products. The cruel exploitation of wild animals’ fuels disease emergence, and the latest COVID-19 pandemic is a prime example of that – the unnecessary close contact between humans and wildlife especially where captive animals are subjected to poor welfare conditions can have catastrophic and devastating effects. Sadly, many tourists who love animals aren’t aware of these risks and may actually contribute to animal suffering simply because they’re unaware of the hidden cruelty. Partner: ABTA, followed by ANVR, has classified certain practices as unacceptable and travel providers working with the guidance manuals have agreed that these unacceptable activities should not be supported or offered for sale to their customers. The 2nd edition of this document introduces these practices and explains what they are. Note that the ANVR addendum to the ABTA Animal Welfare Guidelines adds a few more practices to the existing unacceptable list in the ABTA Manual on ‘Unacceptable Practices’. -

Moving the World 2020 Our Offices

Our offices World Animal Protection International World Animal Protection Brazil World Animal Protection India World Animal Protection Thailand 5th floor, 222 Gray’s Inn Road, Rua Vergueiro, 875 – sala 93 D-21, 2nd Floor, Corporate Park, Floor 27, 253 Asoke, Sukhumvit 21 Road, London, WC1X 8HB, UK 01504-000, São Paulo, Brazil Near Sector-8 Metro Station, Dwarka Sector-21, Klongtoei Nuae, Wattana, T: +44 (0)20 7239 0500 T: +55 (11) 3399-2500 New Delhi – 110077, India Bangkok 10110, Thailand F: +44 (0)20 7239 0653 E: [email protected] T: +91 (0)11 46539341 T: +66 (0) 2007 1767 E: [email protected] worldanimalprotection.org.br E: [email protected] E: [email protected] worldanimalprotection.org worldanimalprotection.org.in worldanimalprotection.or.th World Animal Protection Canada World Animal Protection Africa 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 960, Toronto, World Animal Protection World Animal Protection UK Westside Tower, 9th Floor - No. 901 Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada The Netherlands 5th floor, 222 Gray’s Inn Road, Lower Kabete Road, Westlands, T: +1 416 369 0044 Louis Couperusplein 2 – III London, WC1X 8HB, UK off Brookside Roundabout TF: +1 800 363 9772 2514 HP Den Haag, the Netherlands T: +44 (0)20 7239 0500 P.O. Box 66580-00800, Nairobi, Kenya F: +1 416 369 0147 T: +31 880 2680000 F: +44 (0)20 7239 0653 T: +254 (0)20 217 6598 / E: [email protected] E: [email protected] E: [email protected] +254 (0)727 153 574 worldanimalprotection.ca worldanimalprotection.nl -

WSAVA Animal Welfare Guidelines for Companion Animal Practitioners and Veterinary Teams

WSAVA Animal Welfare Guidelines for companion animal practitioners and veterinary teams ANIMAL WELFARE GUIDELINES GROUP and co-authors of this document: Shane Ryan BVSc (Hons), MVetStud, CVA, MChiroSc, MRCVS (Singapore) Heather Bacon BSc, BVSc, CertZooMed, MRCVS (UK) Nienke Endenburg PhD (Netherlands) Susan Hazel BVSc, BSc (Vet), PhD, GradCertPublicHealth, GradCertHigherEd, MANZCVS (Animal Welfare) (Australia) Rod Jouppi BA, DVM (Canada) Natasha Lee DVM, MSc (Malaysia) Kersti Seksel BVSc (Hons), MRCVS, MA (Hons), FANZCVS, DACVB, DECAWBM, FAVA (Australia) Gregg Takashima BS, DVM (USA) Page | 2 Table of Contents WSAVA Animal Welfare Guidelines Table of Figures ........................................................................................................................... 6 Preamble ..................................................................................................................................... 7 References .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 1: Animal welfare - recognition and assessment ............................................................ 10 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................ 10 Background ....................................................................................................................................... 10 What do we mean by animal welfare? ............................................................................................ -

Kuwaittimes 26-12-2017.Qxp Layout 1

RABI ALTHANI 8, 1439 AH TUESDAY, DECEMBER 26, 2017 Max 21º 32 Pages 150 Fils Established 1961 Min 10º ISSUE NO: 17416 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Amir receives ROTA Cabinet sends Caracal deal Pakistan allows Indian ‘spy’ Don’t miss your Kuwait Times 2 goodwill ambassador 3 to anti-corruption authority 9 on death row to meet family 2018 calendar with today’s issue Committee meeting on jailed MPs aborted over no-shows Opposition blasts absent pro-govt lawmakers By B Izzak Opposition MPs Al-Humaidi Al-Subaei, Mohammad speaker calling on the Assembly to allow them to attend the two MPs. He said the four members should have Al-Dallal and Mohammad Hayef came to the meeting, but the weekly session today and tomorrow, saying they are attended the meeting and expressed their viewpoints in KUWAIT: A meeting of the National Assembly’s legal MPs Ahmad Al-Fadhl, Khaled Al-Shatti, Askar Al-Enezi jailed in violation of the constitution and that their the panel deliberations and not abstain and obstruct the and legislative committee scheduled to discuss the issue and Talal Al-Jallal did not come. For the meeting to be forcible absence undermines the right of voters who committee meeting. He said that this incident will not be of the two jailed lawmakers could not be held yesterday legal, at least four of the seven members must be present. elected them. The two lawmakers also said that their allowed to pass without action. Opposition MP Adel Al- because four pro-government MPs, who are members of The committee was supposed to look into the legal issues absence from attending the session casts suspicion over Damkhi said that the arrest and imprisonment of two MPs the seven-MP committee, did not attend. -

World Animal Protection 2018 Annual Report a Message from the Executive Director

World Animal Protection 2018 Annual Report A Message from the Executive Director Dear Friends, Through your support and commitment, World Animal Protection has made great strides in protecting the lives of animals in 2018. Through our advocacy, initiatives, and efforts, we’ve helped improve the lives of more than 3.6 billion animals around the globe this year. From the plight of stray dogs to protecting animals in the wild, from ensuring the well-being of farm animals to preparing and responding to natural disasters, we continue to fight for the welfare and better treatment of animals everywhere. Here are some of our key accomplishments in the U.S. and beyond in 2018: • We moved supermarket giant Kroger to source their pork exclusively from suppliers and farms that don’t use gestation crates by 2025. • We campaigned for the successful passing of California’s Proposition 12 to prevent farm animal confinement, changing conditions for 40 million egg-laying hens, 12 million pigs, and 65 thousand veal calves. • We moved 200,000 people in in the US to sign our global KFC petition, calling for the fast-food brand to end cruelty to chickens in its supply chains and providing guidance on improving their welfare standards. We delivered the petition with more than half a million worldwide signatures to the company’s headquarters in Louisville, KY. • Through our Global Ghost Gear Initiative, we removed more than 72 tons of discarded fishing gear in Maine and Alaska We also brought Bumble Bee on board to commit to responsible stewardship of their global fisheries. -

Education for Ethics Investigating the Contribution of Animal Studies to Fostering Ethical Understanding in Children by Amanda Jean Yorke

Education for Ethics Investigating the Contribution of Animal Studies to Fostering Ethical Understanding in Children by Amanda Jean Yorke GDip.Eq.St; GCert.Ani.Sci; BEd (Honours) Faculty of Education Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2016 Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Amanda Yorke ii Approval to Copy This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Amanda Yorke iii Statement of Ethical Conduct The research associated with this thesis abides by the international and Australian codes on human and animal experimentation, as approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Tasmania) Network – Social Science, Ethics Reference No. H0013094. Amanda Yorke iv Acknowledgements This thesis is the culminating work of a rare occasion in life to pursue two enduring interests. I am immeasurably grateful for the opportunity to combine my life-long passions of education and animals, and I am fortunate to have been accompanied throughout this pursuit by a number of inspirational individuals, both human and non-human. Firstly, I would like to offer the greatest of appreciation to Dr David Moltow, who achieved the balance between offering expert guidance and allowing a level of autonomy that made this project both possible and pleasurable. -

Global Strategy 2015–2020 Contents

Global Strategy 2015–2020 Contents Moving the world to protect animals 4 We move the world to protect animals – 6 our global strategy on a page Our vision 8 Our mission 10 Our principles 12 Our theory of change 14 Our priority programmes 16 Protecting animals in farming 18 Protecting animals in the wild 20 Protecting animals in communities 26 Protecting animals in disasters 30 Building a global movement to protect animals 34 Transforming the way we work to protect animals 40 3 Moving the world to protect animals For many years we have been a catalyst – technologies in the way we work and plan creatively biggest impact on reducing the scale, duration and intensity moving people, governments, communities and to inspire our audiences to take action. of animal suffering. non-governmental organisations to protect animals across the world. In the past five years alone, we We each have a responsibility to protect the animals Together, we need to build a global movement for animal have made real advances in our work. For example, in our care from needless suffering. By responding to protection with passion and at a pace. This movement by providing rabies vaccinations, we have prevented this context, we can ensure that animal protection will help us mobilise large numbers of people to fund and hundreds of thousands of dogs from being shot, is at the heart of solutions to global issues. support our work. They will join us in calling for lasting and poisoned or beaten to death. By providing emergency global change for animals. feed and veterinary care, we have benefitted millions of animals in disaster prone areas.