C:\Documents and Settings\Compaq Administrator\My

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The First Amendment Implications of Facebook, Myspace, and Other Online Activity of Students in Public High Schools

THE FIRST AMENDMENT IMPLICATIONS OF FACEBOOK, MYSPACE, AND OTHER ONLINE ACTIVITY OF STUDENTS IN PUBLIC HIGH SCHOOLS BRANDON JAMES HOOVER* I. INTRODUCTION The protections of the First Amendment are some of the most basic and fundamental rights guaranteed to all Americans. These protections, however, are not absolute. Although some surveys show that as many as sixty-nine percent of Americans are aware of the First Amendment right to freedom of speech1, it is doubtful that nearly as many Americans are aware of the limitations that have been placed on this enumerated fundamental right. For example, obscene speech2, commercial speech3, indecent speech4, speech tending to incite violence or an imminent response5, and various other forms of speech are not given full constitutional protection. In addition, the free speech rights extended to high school students in public schools are not co-extensive with the rights of adults. In 1969, the Supreme Court held, “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”6 However, since the decision in Tinker, the United States Supreme Court has consistently reduced students’ First Amendment free speech rights. The Court appears to have created a web of tests to determine whether high school students’ First Amendment rights have been * Judicial Clerk for the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals, 21st Circuit; J.D., Ohio Northern University; B.S., Frostburg State University (Law & Society, Political Science, & Sociology). Special thanks to Professor C. Antoinette Clarke, Ohio Northern University. 1 See Press Release, McCormick Foundation, Characters from “The Simpsons” More Well Known to Americans than Their First Amendment Freedoms, Survey Finds (March 1, 2006), http://www.mccormicktribune.org/news/2006/pr030106.aspx (last visited Apr. -

Myspace & Chrysler

Possible Supplementary Material to accompany: Even Giants Can Fall (Microsoft vs. Apple) MySpace vs. Facebook Wikipedia entry on MySpace (excerpts) [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myspace] Myspace (stylized as myspace, previously stylized as MySpace) is a social networking service with a strong music emphasis owned by Specific Media LLC and Justin Timberlake. Myspace was launched in July 2003 and is headquartered in Beverly Hills, California. In April 2014, Myspace had 1 million unique U.S. visitors. Myspace was founded in 2003 by Chris DeWolfe and Tom Anderson, and was later acquired by News Corporation in July 2005 for $580 million. From 2005 until early 2008, Myspace was the most visited social networking site in the world, and in June 2006 surpassed Google as the most visited website in the United States. In April 2008, Myspace was overtaken by Facebook in the number of unique worldwide visitors, and was surpassed in the number of unique U.S. visitors in May 2009, though Myspace generated $800 million in revenue during the 2008 fiscal year. Since then, the number of Myspace users has declined steadily in spite of several redesigns. As of May 2014, Myspace was ranked 982 by total web traffic, and 392 in the United States. In June 2009, Myspace employed approximately 1,600 workers.[2][19] In June 2011, Specific Media Group and Justin Timberlake jointly purchased the company for approximately $35 million.[20] Under new ownership, the company had undergone several rounds of layoffs and by June 2011, Myspace had reduced its staff to around 200. ... suggestions for its demise, including the fact that it stuck to a "portal strategy" of building an audience around entertainment and music, whereas Facebook and Twitter continually launched new features to improve the social- networking experience. -

Subject to Your Confirmation, I Have Appointed Ms

ERIC GARCETTI MAYOR August 14, 2013 Honorable Members of the City Council c/o City Clerk City Hall, Room 395 Honorable Members: Subject to your confirmation, I have appointed Ms. Bich Ngoc Cao to the Board of Library Commissioners for the term ending June 30, 2018. Ms. Cao will fill the vacancy created by Adam Nathanson, whose term expired on June 30, 2013. I certify that in my opinion Ms. Cao is qualified for the work that will devolve upon her, and that I make the appointment solely in the interest of the City. Sincerely, L0f> ERIC GARCETTI Mayor ·EG:dlg Attachment 200 N. SPRING STREET, ROOM 303 LOS ANGELES, CA 90012 (213) 978-0600 MAYOR.LACITY.ORG COMMISSION APPOINTMENT FORM Name: Bich Ngoc Cao Commission: .Board of Library Commissioners End of Term: June 30,2018 Appointee Information 1. Race/ethnicity: Asian Pacific Islander 2. Gender: Female 3. Council district and neighborhood of residence: 13 - East 4. Are you a registered voter? Yes 5. Prior commission experience: ·6. Highest level of education completed: BA, Print Journalism and Political Science, University of Southern California 1. Occupation/profession: Digital Marketing Director, Harvest Records, Capitol Music Group 8. Experience(s) that qualifies person for appointment: See attached resume 9. Purpose of this appointment: Replacement 10. Current composition of the commission (excluding appointee): Appointment Term Commissioner APC CD Ethnicity Gender Date Ends Asian Hirano-Nakanishi, Pacific Marsha J. East 14 Islander F 05-Mar-09 30-Jun-16 South African Madison, Paula Valley 2 American F 10-Auq-10 30-Jun-15 Nathanson, Adam West 5 Caucasian M 29-Mar-13 30-Jun-13 South Tinoco, Eduardo M. -

Social Spaces Final 13 2.Pptx

Social Spaces Stephen Cahill, Brian Collins, Kevin Cooke, Alan Crean, Derek O’Reilly Social Spaces Henri Lefebvre emphasised that in human society “all space is social” A social space is physical or virtual space such as: • A Social Centre • An Online Social Media Forum or Community • Public Places, Websites or Shopping Malls. For this presentaon we will be focusing on Social Cyber Spaces Physical to Cyber History of Social Spaces • Ancient cavemen wrote on their cave walls. • Fast forward a few thousand years and we are all doing it on a computer screen in the form of a Facebook wall A Historical Perspecve Cyber Social Spaces 1997-1998 - SixDegrees.com allowed users to create profiles, list their friends and later, they could surf their Friends lists 1997-2001 – Community tools began supporng various mixes of profiles and publicly linked friends e.g. AsianAvenue, BlackPlanet and MiGente Early 2000’s - Social networking sites (SNSs) developed as a major online phenomenon since the bursng of the Internet bubble 2001 - Cyworld: The Korean virtual world site Cyworld was started in 1999 and added SNS features in 2001 2002 - The rise and fall of Friendster. Issues encountered technology and social difficules 2003 - Many new SNSs were launched, prompng social soware analyst Clay Shirky to coin the term YASNS: “Yet Another Social Networking Service.” The majority of sites were profile-centric What happened to MySpace? • Founder Tom Anderson • MySpace was founded in 2003 to compete with sites like Friendster, Xanga, and AsianAvenue, offering online social networking services. • Rumours started that Friendster was to adopt a fee-based system • Friendster members posted messages encouraging people to join alternate SNSs MySpace was able to grow Indie-rock bands who were rapidly by capitalizing on expelled from Friendster for Friendster’s alienated members failing to comply with profile And then along came Facebook…. -

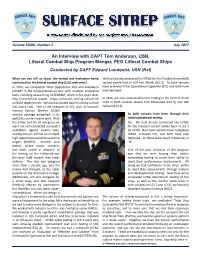

An Interview with CAPT Tom Anderson, USN, Littoral Combat Ship Program Manger, PEO Littoral Combat Ships Conducted by CAPT Edward Lundquist, USN (Ret)

SURFACE SITREP Page 1 P PPPPPPPPP PPPPPPPPPPP PP PPP PPPPPPP PPPP PPPPPPPPPP Volume XXXIII, Number 2 July 2017 An Interview with CAPT Tom Anderson, USN, Littoral Combat Ship Program Manger, PEO Littoral Combat Ships Conducted by CAPT Edward Lundquist, USN (Ret) What can you tell us about the testing and evaluation being We had already conducted the IOT&E for the Freedom (monohull) conducted for the littoral combat ship (LCS) seaframes? variant awhile back in USS Fort Worth (LCS 3). So both variants In 2016, we completed Initial Operational Test and Evaluation have achieved Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and both have (IOT&E) in the Independence-variant, with multiple associated now deployed. tests, including at-sea firing of SEARAM, which is the ship’s Anti- Ship Cruise Missile system. It was successful, scoring a direct hit In 2016, we also conducted live-fire testing in the form of shock on BQM target drones. We also conducted swarm raids by surface trials in both variants aboard USS Milwaukee (LCS 5) and USS fast attack craft. One of the strengths of LCS, with its focused- Jackson (LCS 6). mission Surface Warfare (SUW) mission package embarked, is its So both variants have been through their ability to counter swarm raids. With initial operational testing. the 57mm and the 30 mm guns, we Yes. We had already conducted the IOT&E went out and conducted successful for the Freedom variant awhile back in LCS 3 operations against swarm raids, (in 2013). Now both variants have completed scoring mission kill hits on multiple IOT&E, achieved IOC, and both have now high speed maneuverable seaborne deployed. -

Myspace, Your Space, Or Our Space? New Frontiers in Electronic Evidence

JOHN S. WILSON* MySpace, Your Space, or Our Space? New Frontiers in Electronic Evidence hat began as a back-room experiment between W government and university computer programmers has revolutionized the world as we know it.1 The Internet now * J.D. Candidate, University of Oregon School of Law, 2008. Operations Editor, Oregon Law Review, 2007–08. Law Clerk, U.S. Attorneys Office, 2006–08. First and foremost, I would like to thank Missi Wilson for being a loving and supportive wife as I have pursued my dream of going to law school. I am thankful to have a partner who “lives the adventure” with me. We are also blessed with two wonderful children, Andrew and Samantha, who are constant sources of joy and inspiration. I am indebted to Jeff Evans, an excellent lawyer and an even better friend, for his friendship and helpful comments on this paper. I am also grateful to Assistant U.S. Attorneys William “Bud” Fitzgerald, Sean Hoar, Chris Cardani, Frank Papagni, Kirk Engdall, and John Ray for mentoring me and giving me the best job a law student could ask for. Our country is lucky to have such excellent lawyers working for it. I am tremendously appreciative of the members of Oregon Law Review who helped “sand down” the numerous rough edges of this Article, particularly Executive Editor Megan Thompson, Systems/Managing Editor Harvey Rogers (and his crack team of Staff Editors), and Editor-in-Chief Kirk Neste. Finally, I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge the encouragement I have received during law school from my extended family: the Hilliers, Palmblads, Wilsons, and Gotters. -

Judicial Sentencing Discretion Post-Booker: Are Judges Getting a Distorted View Through the Lens of Social Networking Sites? Christina R

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 27 Article 5 Issue 3 Spring 2011 3-1-2011 Judicial Sentencing Discretion Post-Booker: Are Judges Getting a Distorted View Through the Lens of Social Networking Sites? Christina R. Weatherford Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Christina R. Weatherford, Judicial Sentencing Discretion Post-Booker: Are Judges Getting a Distorted View Through the Lens of Social Networking Sites?, 27 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2011). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol27/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Weatherford: Judicial Sentencing Discretion Post-Booker: Are Judges Getting a JUDICIAL SENTENCING DISCRETION POST- BOOKER: ARE JUDGES GETTING A DISTORTED VIEW THROUGH THE LENS OF SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES? ∗ Christina R. Weatherford INTRODUCTION Jessica Binkerd, a graduate of the University of California, Santa Barbara,1 probably never imagined that pictures taken from her MySpace website would one day help send her to jail. Regrettably, that is exactly what happened. On August 6, 2006, Binkerd was driving her co-worker, twenty-five-year-old Alex Baer, home from a party when she swerved into oncoming traffic and collided with another car.2 Unfortunately, Baer did not survive the accident.3 Binkerd’s blood alcohol level was more than twice the legal limit.4 Binkerd was subsequently charged and convicted of vehicular manslaughter without gross negligence and driving under the influence of alcohol causing injury.5 In 2007, a Santa Barbara superior court judge disregarded the probation department’s recommendation of less than a one year jail sentence,6 opting instead to impose a much harsher penalty of five years and four months in state prison.7 Despite pleas for leniency from the victim’s family,8 ∗ J.D. -

February 2021 Newsletter

BPSRBPSR Escondido Escondido Clubhouse Clubhouse ClubhouseClubhouse ConnectConnect February 2021 Inside this Issue Inside this issue: Feature ........................ 1 Self Care ..................... 2 Recovery Tool Time ... 3 Spotlights ..................... 4 What I Love................. 6 Pet of the Month ........ 8 Food & Dining ............ 9 Fun & Games ............. 10 Art & Facts .................. 11 Helpful links ................. 12 Photos by Jill R BPSR Escondido Clubhouse 474 Vermont Ave Lunch at the Clubhouse Suite 105 By Chris L Escondido, CA 92026 Escondido Clubhouse Coordinator Lileigh and and it's nice that they serves free lunch to mem- she told me that she gets keep us fed. (760) 737-7125 bers five days a week donations from Smart and If you want to help from 10 AM - 12 PM. Final, Deanna’s Gluten contribute to the club- https://www.mhsinc.org/listing/ Remember to sign up be- Free Bakery, and Grocery house, have your family bpsr-escondido-clubhouse-2/ fore 10 AM. Three of Outlet. Jeannette cooks and friends make a tax- those days, Wednesday, on Wednesdays, Kersten deductible donation Thursday, and Friday, are cooks on Thursdays, and which can help with hot lunches. Friday is piz- Lileigh cooks on Fridays. lunches: gofundme.com/ za day! I think the staff at the f/campaign-for-the-bpsr- I talked to Clubhouse clubhouse are amazing escondido-clubhouse SELF LOVE The Newsroom: Loving Yourself Like Editorial: Chris L, Cindy T, You Love Your Friends David D, Lileigh W, Katherine W, Terra J by Carmen D Layout: Cindy T, Terra J, Jill R Writing: Carmen D, Chris L, Cindy T, Terra J Photography: Carmen D, Candace L, Chris L, Jazmine L, Jill R Advisor: Jill R Photo by Carmen D As Valentine's Day is almost up- to a good breakfast. -

The Impact of Myspace on Music and Entertainment 11

02 Chapter 02 4/21/07 10:21 AM Page 9 The Impact of MySpace on 2 Music and Entertainment usic industry insiders and watchers have definitely taken notice of MySpace’s impact on music and entertainment. The Mold models of the music industry—record deal, mass radio play, major distribution—have been turned on their ears a bit. That’s not to say that the standard business model is irrelevant. It’s still vital in achieving mass-market penetration. But now there’s a change in how musicians can get their songs heard. They’re no longer solely reliant on radio as a means of reaching consumer ears, nor are they dependent on a record label for selling music. Instead, artists can market themselves directly to consumers, who in turn pass the word on to their friends. The web in general has made a direct-to-consumer approach possible for a long time now, but not until the proliferation of MySpace users who love music was there a ready-made community just sitting there waiting to hear the next big music star. In this chapter we’ll take a brief look at how MySpace has affected the landscape of the entertainment industry. In the Beginning… The generally accepted story of MySpace’s founding is that two guys from California, Tom Anderson and Chris DeWolfe, created the site in 2003 along with a small group of programmers. It may have started as a new way to keep people in the know about local Los Angeles bands and club gigs, but it grew into a place to meet new friends and keep in touch with old. -

Geosciences198993univ.Pdf

UNIVLK6IIY Qf ILLINOIS Mt AX URBANkfiUAMPAIGN MIG 3 1 2000 NOTICE: Return or renew all Library Materials! The Minimum Fee tor each Lost Book is $50.00. The person charging this material is responsible for its return to the library from which it was withdrawn on or before the Latest Date stamped below. Theft, mutilation, and underlining of books are reasons for discipli- nary action and may result in dismissal from the University. To renew call Telephone Center, 333-8400 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN FEB 2 iter L161—O-1096 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://www.archive.org/details/geosciences198993univ <a GeoSciences Department of Geology FAL L 198 9 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS }^U Faculty and Staff Letter from the Head < Departmental News Profile: R.James Kirkpatrick -O Alumni News -^>- Reply Form ^> FAL L 1989 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS Department of Geology, GeoSciences is the alumni newsletter for the published in University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. It is September and February of each year. Department Head: R. James Kirkpatrick GeoSciences Fall 1989 Assistant to tbe Head: Department of Geology Peter A. Mlchalove University of Illinois at Editor: Urbana-Champaign Johlas Michelle Sanden 24S Natural History Bldg. Designer: 1301 W. Green Street Jessie J. Knoi llrbana, III. 61801-2999 Administrative Secretary (217) 333-3542 Patricia Lane GeoSciences Faculty Graduate Students Stephen P. Altaner, assistant professor Istvan Barany Jr., TA David E. Anderson, professor David Breedon, TA Thomas F. Anderson, professor/associate dean, Ten-Hung Chu, TA LAS Xian-Dong Cong, RA Jay Bass, associate professor Tom Corbet, RA Cameron Begg, research microprobe analyst James A. -

Music As Cultural Glue: Supporting Bands and Fans On

Music as Cultural Glue: Supporting Bands and Fans on MySpace Irina Shklovski danah boyd Carnegie Mellon University University of California-Berkeley [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT flavored MySpace from its conception. One of MySpace The roots of MySpace.com are deeply entwined with music founders, Tom Anderson, known as simply Tom to most culture. By explicitly engaging musicians in the design MySpace subscribers, had been in numerous rock bands process, MySpace has allowed musicians to create a digital since his teenage years. One of Anderson’s early strategies identity and connect with fellow musicians and fans. This was to welcome populations that had been kicked off paper explores how MySpace designed for bands, the Friendster. He intentionally provided a space for musicians supportive community that musicians were able to create that were seeking a way to directly connect with their fans for themselves, the symbiotic relationship between and promote themselves. musicians and fans, how music serves as cultural glue, and how designers can learn from MySpace’s decisions. MySpace was launched from Santa Monica, California in fall of 2003. Los Angeles hipsters immediately adopted it. Author Keywords Indie rock bands were central to this community and bands MySpace, music, community, fans, social network sites that were deleted by Friendster found a safe haven on MySpace. Band managers, club promoters, and independent INTRODUCTION musicians leveraged the site to promote local bands and In May 2006 Jupiter Research released a report which provide VIP access to a handful of premier clubs. announced that a social network site MySpace generates When Anderson realized that musicians were joining the more community-related music activity than any other site, he contacted them to ask what he could do to support music-related site [5]. -

A Jay Adelson

A JAY ADELSON CEO of Digg Born: September 7, 1970; Detroit, Michigan In 1988, Adelson graduated from Cranbrook Died: - Schools, a private college preparatory school located in Primary Field: Internet Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. That autumn he enrolled in Specialty: Social media Boston University, graduating in 1992 with a degree in Primary Company/Organization: Digg film and broadcasting, having minored in computer sci- ence. After graduation, Adelson moved to San Rafael, INTRODUCTION California, because he had an unpaid internship as a One of the founders and the first chief executive officer sound engineer at Skywalker Sound. To earn money, (CEO) of the social news website Digg, Jay Adelson started with Netcom, one of the first wide-scale Internet providers, and was among the industry representatives called to testify before the U.S. House of Representa- tives’ Homeland Security Subcommittee on Cybersecuri- ty, Infrastructure Protection, and Security Technologies on the role of the private sector in securing the Internet. After leaving Digg in 2010, he became the CEO of SimpleGeo, Inc., a position he held for less than a year before the company was purchased by Urban Airship. He continues to serve as an adviser for SimpleGeo. EARLY LIFE Jay Steven Adelson was born on September 7, 1970, in Detroit, Michigan, and grew up in the suburb of South- field. His parents, Sheldon and Elaine Adelson, were schoolteachers during his early childhood; then his fa- ther inherited a small electric supply store in Detroit that he strove to build into a sustainable business. His parents lost both the business and their house during a recession that hit Detroit hard in the late 1980s.