A Case for Debt Financing in Indian Impact Enterprises by Sudarshan Sampathkumar, Sam Whittemore, Ramraj Pai, and Swasti Saraogi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![India Weekly Newsletter]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4906/india-weekly-newsletter-64906.webp)

India Weekly Newsletter]

India January 30 Weekly Newsletter 2012 This document covers news related to India with a special focus on areas like mergers & acquisitions, private equity & venture capital. Volume 121, January 30th, 2012 For the period January 23, 2012 to January 29, 2012 January 30, 2012 [INDIA WEEKLY NEWSLETTER] Highlights Ocean Sparkle Calls Off TAG Offshore Acquisition…(3) ONGC Videsh To Acquire 15% Stake In OAO Yamal…(4) Content Pages Mitsubishi Electric Corp Acquires Pune Based Mergers & Acquisitions News 3-5 Messung Group…(5) Mergers & Acquisitions Deals 5-8 Strides Arcolab Sells Ascent Pharmahealth To Watson Pharma…(6) Private Equity News 8-10 VG Siddhartha’s Coffee Day Group Ups MindTree Stake To 18%…(7) Private Equity Deals 10-12 Temasek to invest Rs685 cr In Godrej Venture Capital News 12-12 Consumer for 5% Stake…(8) Venture Capital Deals 13-14 Ansal Properties to raise Rs300 cr for Gurgaon Project…(9) India Infoline Venture Capital Fund Raises Rs 500 cr Realty Fund…(10) KIMS Raises Rs170 cr From OrbiMed, Ascent Capital…(11) IL&FS Buys Logix Group's Noida Property For Rs600 cr…(12) Online Jewellery Store BlueStone.com Raises $5 mn VC Funding…(13) Sequoia Invests Rs20 cr In E-Recharge Portal- Freecharge.in…(13) InRev Systems Raises SeriesA Funding…(14) Confidential LKP Securities Limited 2 January 30, 2012 [INDIA WEEKLY NEWSLETTER] Mergers & Acquisitions News Ocean Sparkle Calls Off TAG Offshore Acquisition Ocean Sparkle's acquisition talks with TAG offshore have not fructified. P Jairaj Kumar - chairman and MD of Ocean Sparkle did not elaborate on the reason for not going ahead with the $100 mn proposal, citing a confidentiality clause with TAG Offshore. -

Private Debt: the Hunt for Yield

Private Debt: The Hunt For Yield Old Hill Partners, Inc. 1120 Boston Post Road, 2nd Floor Darien, CT 06820 Executive Summary Seven years after the financial crisis and the global onset of ZIRP and QE monetary policies, investors are still confronted with few options when it comes to generating yield from traded credit and equity vehicles. However, economic growth, while measured, has been sufficient to meaningfully lower default rates on privately-placed corporate debt. Accordingly, investors are discovering the qualities inherent in this overlooked and relatively undiscovered asset class, primarily shorter duration and yield premiums in excess of those available from comparable traded credit instruments. At the same time, tighter banking regulations have made it unfeasible and uneconomical for large financial institutions to lend to small and medium-sized businesses - precisely the corporate segment most in need to growth and expansionary capital - and they are increasingly turning to non-bank providers as a source of financing. This situation creates an attractive supply-demand dynamic between the companies that need capital and participants than can provide credit. When properly vetted and constructed, such private debt transactions increasingly offer the potential to generate attractive risk-adjusted returns for prudent investors. © 2015 Old Hill Partners, Inc.. Page 2 of 10 What is Private Debt? Private debt allows investors to act as a direct lender to private companies instead of through an intermediating financial institution. It is generally illiquid and not traded in organized markets, but is backed by corporate credit (such as cash flow), real estate, infrastructure, or other hard, financial or esoteric assets. -

Corporate Venturing Report 2019

Tilburg University 2019 Corporate Venturing Report Eckblad, Joshua; Gutmann, Tobias; Lindener, Christian Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Eckblad, J., Gutmann, T., & Lindener, C. (2019). 2019 Corporate Venturing Report. Corporate Venturing Research Group, TiSEM, Tilburg University. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. sep. 2021 Corporate Venturing 2019 Report SUMMIT@RSM All Rights Reserved. Copyright © 2019. Created by Joshua Eckblad, Academic Researcher at TiSEM in The Netherlands. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LEAD AUTHORS 03 Forewords Joshua G. Eckblad 06 All Investors In External Startups [email protected] 21 Corporate VC Investors https://www.corporateventuringresearch.org/ 38 Accelerator Investors CentER PhD Candidate, Department of Management 43 2018 Global Startup Fundraising Survey (Our Results) Tilburg School of Economics and Management (TiSEM) Tilburg University, The Netherlands 56 2019 Global Startup Fundraising Survey (Please Distribute) Dr. -

Corporate Venturing Report 2019

Corporate Venturing 2019 Report SUMMIT@RSM All Rights Reserved. Copyright © 2019. Created by Joshua Eckblad, Academic Researcher at TiSEM in The Netherlands. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS LEAD AUTHORS 03 Forewords Joshua G. Eckblad 06 All Investors In External Startups [email protected] 21 Corporate VC Investors https://www.corporateventuringresearch.org/ 38 Accelerator Investors CentER PhD Candidate, Department of Management 43 2018 Global Startup Fundraising Survey (Our Results) Tilburg School of Economics and Management (TiSEM) Tilburg University, The Netherlands 56 2019 Global Startup Fundraising Survey (Please Distribute) Dr. Tobias Gutmann [email protected] https://www.corporateventuringresearch.org/ LEGAL DISCLAIMER Post-Doctoral Researcher Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG Chair of Strategic Management and Digital Entrepreneurship The information contained herein is for the prospects of specific companies. While HHL Leipzig Graduate School of Management, Germany general guidance on matters of interest, and every attempt has been made to ensure that intended for the personal use of the reader the information contained in this report has only. The analyses and conclusions are been obtained and arranged with due care, Christian Lindener based on publicly available information, Wayra is not responsible for any Pitchbook, CBInsights and information inaccuracies, errors or omissions contained [email protected] provided in the course of recent surveys in or relating to, this information. No Managing Director with a sample of startups and corporate information herein may be replicated Wayra Germany firms. without prior consent by Wayra. Wayra Germany GmbH (“Wayra”) accepts no Wayra Germany GmbH liability for any actions taken as response Kaufingerstraße 15 hereto. -

Printmgr File

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q È QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the quarterly period ended June 30, 2018 OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission File Number 1-11758 (Exact Name of Registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 1585 Broadway 36-3145972 (212) 761-4000 (State or other jurisdiction of New York, NY 10036 (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) (Registrant’s telephone number, incorporation or organization) (Address of principal executive including area code) offices, including zip code) Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes È No ‘ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§ 232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to submit and post such files). Yes È No ‘ Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant is a large accelerated filer, an accelerated filer, a non-accelerated filer, smaller reporting company, or an emerging growth company. -

Fintech Monthly Market Update | July 2021

Fintech Monthly Market Update JULY 2021 EDITION Leading Independent Advisory Firm Houlihan Lokey is the trusted advisor to more top decision-makers than any other independent global investment bank. Corporate Finance Financial Restructuring Financial and Valuation Advisory 2020 M&A Advisory Rankings 2020 Global Distressed Debt & Bankruptcy 2001 to 2020 Global M&A Fairness All U.S. Transactions Restructuring Rankings Advisory Rankings Advisor Deals Advisor Deals Advisor Deals 1,500+ 1 Houlihan Lokey 210 1 Houlihan Lokey 106 1 Houlihan Lokey 956 2 JP Morgan 876 Employees 2 Goldman Sachs & Co 172 2 PJT Partners Inc 63 3 JP Morgan 132 3 Lazard 50 3 Duff & Phelps 802 4 Evercore Partners 126 4 Rothschild & Co 46 4 Morgan Stanley 599 23 5 Morgan Stanley 123 5 Moelis & Co 39 5 BofA Securities Inc 542 Refinitiv (formerly known as Thomson Reuters). Announced Locations Source: Refinitiv (formerly known as Thomson Reuters) Source: Refinitiv (formerly known as Thomson Reuters) or completed transactions. No. 1 U.S. M&A Advisor No. 1 Global Restructuring Advisor No. 1 Global M&A Fairness Opinion Advisor Over the Past 20 Years ~25% Top 5 Global M&A Advisor 1,400+ Transactions Completed Valued Employee-Owned at More Than $3.0 Trillion Collectively 1,000+ Annual Valuation Engagements Leading Capital Markets Advisor >$6 Billion Market Cap North America Europe and Middle East Asia-Pacific Atlanta Miami Amsterdam Madrid Beijing Sydney >$1 Billion Boston Minneapolis Dubai Milan Hong Kong Tokyo Annual Revenue Chicago New York Frankfurt Paris Singapore Dallas -

The Pe & M&A Quarterly

JUNE 2020 JUNE 2020 | ISSUE 4 THE PE & M&A QUARTERLY Quarterly News, Trends and Developments Off the Record “The COVID-19 pandemic has adversely affected all sectors in India and across the globe, except a few. Though initially it was expected that the pandemic would end in a few months, it appears that it will continue for a longer period. Many PE firms and strategic investors have paused or deferred or slowed down their investment plans for the next 6 to 8 months. However, there are exceptions in case of a few. The deal making activity in India appears uncertain for the remainder of this year. On the M&A side, domestic deals are being evaluated. It is getting harder to close transactions in view of mismatch in expectations of the seller and buyer. The present situation has forced them to realign their objectives and expectations. In signed deals, material adverse change clauses are being evaluated, and in new deals it is being made as exhaustive as possible to ensure possible exit in case of change in environment. The overall structure of doing deals is going through a change and the focus is shifting to value creation and sustainability. There is a reasonable possibility that towards the end of the year, if we return to some sense of normalcy, there will be a significant increase in M&A and PE activity.” Satish Kishanchandani, Managing Partner FEATURED JUDGEMENT Banyan Tree Growth Capital vs Axiom Cordages Limited and Ors. 1 ISSUE 4 JUNE 2020 LEGAL UPDATES NON-FATF MEMBERS ALLOWED TO REGISTER AS CATEGORY I-FPI SEBI Updates April 07, 2020: The Securities and Exchange Board of India (“SEBI”) has relaxed the rules with respect to SNAPSHOT offshore funds seeking to get registered under the • For all relevant COVID-19 relaxations in “properly regulated” Foreign Portfolio Investor (“FPI”) compliances permitted by SEBI, visit our category. -

RBSA India Deals Snapshot – February 2015

India Deals IndiaSnapshot Deals FEBRUARYSnapshot 2015 November 2014 Index Snapshot of Mergers & Acquisitions Update for 4 February 2015 Mergers & Acquisitions Deals for February, 2015 5 - 7 Summary of Mergers & Acquisitions Update 8 Snapshot of PE / VC Update for February, 2015 10 - 12 PE / VC Deals for February, 2015 13 - 20 Summary of PE / VC Update 21 Real Estate Deals for February, 2015 23 RBSA Range of Services 24 Contact Us 25 Merger & Acquisition Update 3 Snapshot of Mergers & Acquisitions Update for FEBRUARY 2015 Acquirer Target Sector Stake Rs. (In Cr.) Sila Solutions Private Ltd. Evocare Pest Control Solutions Others 51% N.A. Exotel Techcom Pvt. Ltd. Blank Page Innovations Pvt. Ltd. IT/ITES N.A. N.A. AliPay (China) Internet Technology One97 Communications Ltd. IT/ITES 25% N.A. Company Ltd. Foodpanda GmbH JustEat Food & Beverages N.A. N.A. Warren Tea Ltd. Pressman Advertising Ltd. Media & Entertainment 8.52% ` 7 Cr. Future Consumer Enterprises Ltd. Integrated Food Park Private Ltd. Food & Beverages 28.86 N.A. Adfactors PR Pvt. Ltd. Yorke Communications IT/ITES N.A. N.A. RJ Corp iClinic Healthcare Pvt. Ltd. Healthcare N.A. N.A. Bigtree Entertainment Pvt. Ltd Eventifier Media & Entertainment N.A. ` 6.18 Cr. Quadragen Vet Health Private Ltd. Karnataka Nutraceutical Healthcare N.A. N.A. Ipca Laboratories Ltd. Krebs Biochemicals & Industries Ltd. Pharmaceuticals 16.73% ` 9.54 Cr. Natures Basket Ltd. EkStop Shop Pvt. Ltd. E-commerce N.A. N.A. Snapdeal Exclusively.in E-commerce 100% N.A. Tekni-Plex Inc., Ghiya Extrusions Private Ltd. Manufacturing N.A. N.A. -

9Th March to 22Nd March 2019 BFSI Newsletter Investment and Exit

9th March to 22nd March 2019 BFSI Newsletter Investment and Exit Indian Angel Network invests Rs. 3.5 crore in Pune-based automobile parts startup SparesHub 15TH March 2019.Zeebiz Indian Angel Network has invested Rs 3.5 crore in Pune-based start-up SparesHub, an automobile parts start-up. SparesHub will utilise the funds for its geographical expansion and to strengthen its technology capabilities...more Binny Bansal and others invest $ 65 mn in Acko general insurance 13TH March 2019.Asia Insurance Post Tech based general insurer Acko has raised $65 million in its Series C financing round, from Binny Bansal, co-founder of Flipkart; RPS Ventures, led by KabirMisra, ex- managing partner at Softbank; and Intact Ventures Inc. - corporate venture arm of Canada's largest property & casualty insurer...more Fund Raise Punjab & Sind Bank to raise equity capital of Rs 500 cr via QIP 15TH March 2019.Money Control State-owned Punjab & Sind Bankon Friday said it would raise up to Rs 500 crore by issuing fresh equity shares through qualified institutional placement...more Allahabad Bank looks to raise Rs 500 crore via non-core asset sale 16TH March 2019.Business Standard Allahabad Bank expects to raise about Rs 500 crore from the sale of its non-core assets. These assets include the bank's 28.52 per cent stake in Universal Sompo General Insurance, and about 12 properties across India...more Karur Vysya Bank Raises Rs 487 Cr 13TH March 2019.Business world Karur Vysya Bank on Wednesday said it has raised Rs 487 crore through Basel-III compliant bonds to fund its growth plans. -

Grant Thornton India LLP

Dealtracker Providing M&A and Private Equity Deal Insights 8th Annual Edition 2012 © Grant Thornton India LLP. All rights reserved. This document captures the list of deals announced based on information available in the public domain and based on public announcements. Grant Thornton India LLP does not take any responsibility for the information, any errors or any decision by the reader based on this information. This document should not be relied upon as a substitute for detailed advise and hence, we do not accept responsibility for any loss as a result of relying on the material contained herein. Further, our analysis of the deal values are based on publicly available information and based on appropriate assumptions (wherever necessary). Hence, if different assumptions were to be applied, the outcomes and results would be different. © Grant Thornton India LLP. All rights reserved. 2 Contents From the 4 - Foreword Editor's Desk 6 - Year Round Up 2012: 10 – M&A Round Up Mergers & 15 – Domestic Acquisitions 17 – Cross border 1001 25 – PE Round Up Private 27 – Top Deals Equity 29 – PE – Sector Highlight 31 – PE – City Break up deals Other 33 – IPO & QIP Features 35 – Deal List $49bn © Grant Thornton India LLP. All rights reserved. 3 Foreword The on-going Eurozone worries, weakening rupee and Contrary to expectations, inbound deal activity reverted a uncertain Indian economy with a slowdown in the to the single-digit levels seen in 2010, notching up US$ reform process, impacted M&A deal activity in certain 7 bn in deal value, after putting in a robust performance periods of 2012. -

PDF: 300 Pages, 5.2 MB

The Bay Area Council Economic Institute wishes to thank the sponsors of this report, whose support was critical to its production: The Economic Institute also wishes to acknowledge the valuable project support provided in India by: The Bay Area Council Economic Institute wishes to thank the sponsors of this report, whose support was critical to its production: The Economic Institute also wishes to acknowledge the valuable project support provided in India by: Global Reach Emerging Ties Between the San Francisco Bay Area and India A Bay Area Council Economic Institute Report by R. Sean Randolph President & CEO Bay Area Council Economic Institute and Niels Erich Global Business/Transportation Consulting November 2009 Bay Area Council Economic Institute 201 California Street, Suite 1450 San Francisco, CA 94111 (415) 981-7117 (415) 981-6408 Fax [email protected] www.bayareaeconomy.org Rangoli Designs Note The geometric drawings used in the pages of this report, as decorations at the beginnings of paragraphs and repeated in side panels, are grayscale examples of rangoli, an Indian folk art. Traditional rangoli designs are often created on the ground in front of the entrances to homes, using finely ground powders in vivid colors. This ancient art form is believed to have originated from the Indian state of Maharashtra, and it is known by different names, such as kolam or aripana, in other states. Rangoli de- signs are considered to be symbols of good luck and welcome, and are created, usually by women, for special occasions such as festivals (espe- cially Diwali), marriages, and birth ceremonies. Cover Note The cover photo collage depicts the view through a “doorway” defined by the section of a carved doorframe from a Hindu temple that appears on the left. -

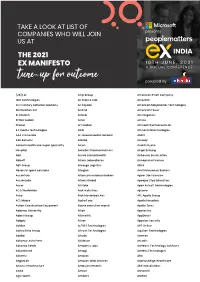

Partial List Ex Conference 20

Artemis Health Institute Bharat Serums & Vaccines Carrier CP Milk & Food Products Discovery FCDO GlaxoSmithkline Henkel India Shelter Finance Corporation Kadtech Infraprojects LSEG MIND NIIT Paytm Money PT Bank BTPN RTI Shyam Spectra Stryker ThoughtWorks ValueMined Technologies Y-Axis Solutions Arth Group Bharti Axa Life Insurance Cars24 CP Plus Dksh FE fundinfo Glenmark Pharmaceuticals Herbalife Nutition IndiaMART Kaivalya Educatiion Foundation LTI MindTickle Nineleaps technology solutions PayU PT. Media Indra Buana Ruby Seven Studios Shyam Spectra STT Global Data Centres Thryve Digital Valuex Technologies Yamaha Motor Arvind Fashions Bhel Caterpillar CP Wholesale DLF Fedex GlobalEdge Here Technologies Indigo Kalpataru Luminous Power Technologies Mindtree Nippon Koei PCCPL PTC Network Rustomjee Sidel Successive Technologies Tierra Agrotech Varroc Engineering Yanbal Asahi India Glass BIC CDK Global CPI DMD ADVOCATES Ferns n Petals GlobalLogic Herman Miller Indmoney Kama Ayurveda Luthra Group MiQ Digital NISA Global PCS Publicis Media S P Setia Siemens Sulzer Pumps Tifc Varuna Group Yanmar TAKE A LOOK AT LIST OF Ashirvad Pipes Bidgely Technologies CEAT Creditas Solutions DP World Ferrero GMR Hero Indofil industries Kanishk Hospital Luxury Personified Mizuho Bank Nissan Peak Infrastructure Management PUMA Group S&P Global Sigma AVIT Infra Services Summit Digitel Infrastructure TIL Vastu Housing Finance Corpora- Yara COMPANIES WHO WILL JOIN Asian paints Bigtree Entertainment Celio Cremica Dr Reddy's Ferring Pharmaceuticals Godrej & Boyce