Anthropological Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIVIL TRANSPORTERS - BAHRIA COLLEGE KARSAZ Transport Incharge : Javed Amjad Kayani: 0343-2432072 - 0302-5723178

CIVIL TRANSPORTERS - BAHRIA COLLEGE KARSAZ Transport Incharge : Javed Amjad Kayani: 0343-2432072 - 0302-5723178 S# Name Contact # Vehicle Route Morning & Evening 1 Abdul Salam 3002185124 Hiace Saddar, Garden, Jamshed Road 2 Abid Sheikh 3002454876 Hiroof University, Gulistan-e-Johar, Kiran Hospital 3 Amin Ud Din 3002519301 Hiace PIB Colony, Jamshed Raod, Chandni Chok, Bahadurabad 4 Shahbaz 3139030400 Hiroof Dalmian NHS Phase I & II 5 Asif 3432468290 Hiroof Shah Faisal, Rafay e Ama, Jumma Goth, Green Town 6 Atta Ullah 3332224684 Hiroof Majeed SRE, Dalmia 7 Bilal 3320337639 Hiace Manzor Colony DHA Phase II Qayumabad 8 Faisal Abbas 3462593009 Mazda Nagan Chorangi, Disco Bakery, Maskan 9 Farhat Abbas 3002327290 Coaster Gulshan-e-Jamal, Gulistan-e-Jouhar, Rabia City 10 Fiaz 3101288299 Hiace Azizabad, Karimabad, Gol Market 11 Haseeb 3162594642 Hiace 4K, Bufferzone, Shafi Mor, Sohrab Goth 12 Imran 3338999790 Hiroof Baloch Colony, Manzoor Colony 13 Imran Burfat 3213380750 Hiroof Dalmia 14 Islam ud Din 3332294481 Coaster Gulistan-e-Johar 15 Jamil ud Din 3003645880 Coaster Shah Faisal Colony 16 Jaseem Ahmed Khan 3002484125 Hiroof saudi Town, Safora, Malir Cantt, Karachi Universty falcon 17 K M Yaqoob 3002170136 Mazda Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Mochi Mor, Expo Centre 18 Kaleem 3462695707 Coaster Essa Nagri, Azizabad, Tahir Villa, 4K Chorangi 19 Khan Baba 3332294959 Hiace Bhadurabad, Sharfabad, Guru Mander, Soldier Bazar 20 M Aqil 3161605887 Hi-Roof Shah Faisal 1 , 2 , 3 and 5 Golden Town 21 M Yamin 3012721186 Hiace Nursery, NORE-I, Lucky Star 22 M. Akbar 3002157893 Hiroof Clifton,Seaview,Teen Talwar,NORE II Sharahefaisal 23 M. Farooq Patel 3073516561 Hiace Landhi, Quaidabad 24 M. -

Final GCR Combined Copy May 2013

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY FOR GLOBAL / COUNTRY STUDY REPORT (Subject Code: 2830003) ON “PAKISTAN WITH RESPECT TO LEATHER INDUSTRY” SUBMITTED TO MBA-732: SEMESTER-III & IV LDRP-INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY AND RESEARCH, GANDHINAGAR. [In partial Fulfillment of the Requirement of the award for the degree of Master of Business Administration (MBA)] By Gujarat Technological University, Ahmedabad Year: 2013 Semester III & IV Guided By: Name of Guides email Id Contact Designation No. Mr. Vinit M. Mistri [email protected] 09998873083 Lecturer Ms. Hemali G. Broker [email protected] 09099012233 Lecturer Dr. Pooja M. Sharma [email protected] 09726480698 Assistant professor Ms. Sejal C. Acharya [email protected] 07698029293 Lecturer Mr. Anand Nagrecha [email protected] 09824090958 Lecturer Student’s Declaration We hereby declare that the Global/ Country Study Report titled “GLOBAL / COUNTRY STUDY REPORT (Subject Code: 2830003) ON“PAKISTAN WITH RESPECT TO LEATHER INDUSTRY” in ( PAKISTAN ) is a result of our own work and our indebtedness to other work publications, references, if any, have been duly acknowledged. If I/we are found guilty of copying any other report or published information and showing as my/our original work, or extending plagiarism limit, I understand that I/we shall be liable and punishable by GTU, which may include ‘Fail’ in examination, ‘Repeat study & re Submission of report’ or any other punishment that GTU may decide. Place: Gandhinagar Date: All Students undersigned below. Enrollment Number NAME OF THE STUDENT -

East-Karachi

East-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 East Karachi Jamshed Town 1-Akhtar Colony 408070173 GBLSS - H.M.A. Middle Mixed 7,841 1,568 4,705 3,137 1,568 6,273 25,093 6,273 31,366 2 East Karachi Jamshed Town 2-Manzoor Colony 408070139 GBPS - BILAL MASJID NO.2 Primary Mixed 12,559 2,512 10,047 2,512 2,512 10,047 40,189 10,047 50,236 3 East Karachi Jamshed Town 2-Manzoor Colony 408070174 GBLSS - UNION Middle Mixed 16,613 3,323 13,290 3,323 3,323 13,290 53,161 13,290 66,451 4 East Karachi Jamshed Town 9-Central Jacob Line 408070171 GBLSS - BATOOL GOVT` BOYS`L/SEC SCHOOL Middle Mixed 12,646 2,529 10,117 2,529 2,529 10,117 40,466 10,117 50,583 5 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070160 GBLSS - AZMAT-I-ISLAM Middle Boys 22,422 4,484 17,937 4,484 4,484 17,937 71,749 17,937 89,687 6 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070162 GBLSS - RANA ACADEMY Middle Boys 13,431 2,686 8,059 5,372 2,686 10,745 42,980 10,745 53,724 7 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070163 GBLSS - MAHMOODABAD Middle Boys 20,574 4,115 12,344 8,230 4,115 16,459 65,836 16,459 82,295 8 East Karachi Jamshed Town 11-Garden East 408070172 GBLSS - GULSHAN E FATIMA Middle Mixed 16,665 3,333 13,332 3,333 3,333 13,332 53,327 13,332 66,658 9 East Karachi Gulshan-e-Iqbal Town 3-PIB -

A Survey of Human Rights 2013

Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2013 www.HAFsite.org June 5, 2013 © Hindu American Foundation 2013 “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, Article 1 “One should never do that to another which one regards as injurious to one’s own self. This, in brief, is the rule of dharma. Yielding to desire and acting differently, one becomes guilty of adharma.” Mahabharata XII: 113, 8 “Thus, trampling on every privilege and everything in us that works for privilege, let us work for that knowledge which will bring the feeling of sameness towards all mankind.” Swami Vivekananda, “The Complete works of Swam Vivekananda,” Vol 1, p. 429 "All men are brothers; no one is big, no one is small. All are equal." Rig Veda, 5:60:5 © Hindu American Foundation 2013 © Hindu American Foundation 2013 Endorsements of Hindu American Foundation's Seventh Annual Report Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2010 "As the founder and former co---chair of the Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans, I know that the work of the Hindu American Foundation is vital to chronicle the international human rights of Hindus every year. The 2010 report provides important information to members of Congress, and I look forward to continuing to work with HAF to improve the human rights of Hindus around the world." U.S. Congressman Frank Pallone (D-NJ) "As Chairman of the Subcommittee on Terrorism and the co---chair of the Congressional Caucus on India and Indian Americans, I applaud the hard work of the Hindu American Foundation in producing their annual Human Rights Report. -

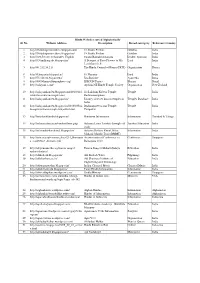

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Hindus in South Asia & the Diaspora: a Survey of Human Rights 2007

Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2007 www.HAFsite.org May 19, 2008 “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights” (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948, Article 1) “Religious persecution may shield itself under the guise of a mistaken and over-zealous piety” (Edmund Burke, February 17, 1788) Endorsements of the Hindu American Foundation's 3rd Annual Report “Hindus in South Asia and the Diaspora: A Survey of Human Rights 2006” I would like to commend the Hindu American Foundation for publishing this critical report, which demonstrates how much work must be done in combating human rights violations against Hindus worldwide. By bringing these abuses into the light of day, the Hindu American Foundation is leading the fight for international policies that promote tolerance and understanding of Hindu beliefs and bring an end to religious persecution. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) Freedom of religion and expression are two of the most fundamental human rights. As the founder and former co-chair of the Congressional Caucus on India, I commend the important work that the Hindu American Foundation does to help end the campaign of violence against Hindus in South Asia. The 2006 human rights report of the Hindu American Foundation is a valuable resource that helps to raise global awareness of these abuses while also identifying the key areas that need our attention. Congressman Frank Pallone, Jr. (D-NJ) Several years ago in testimony to Congress regarding Religious Freedom in Saudi Arabia, I called for adding Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists to oppressed religious groups who are banned from practicing their religious and cultural rights in Saudi Arabia. -

The-Index-Of-Religious-Diversity-And-Inclusion-In-Pakistan-1.Pdf

The Index of Religious Diversity and Inclusion in PAKISTAN An Exploratory Study with Initial Recommendations Copyright @ 2020 by Asif Aqeel Author: Asif Aqeel Research Oversight: Centre for Public Policy and Governance (CPPG) Editor: Asher John Research Assistants: Mary Gill, Basil Dogra Surveyors: Mary Gill, Sunil Gulzar, Basil Dogra, Asher Aryan Photo Credits: Saad Sarfaraz Sheikh All Rights Reserved First Edition Printed in Lahore, Pakistan Published by Centre for Law and Justice (CLJ) www.clj.org.pk For suggestions: [email protected] Contents Table of Contents Abbreviations 7 Acknowledgment 8 Executive Summary 9 Chapter1: Introduction 12 Chapter 2: Background 14 Chapter 3: Pakistan: The Land of Equalities 20 The Changing Status of Religious Minorities 23 Liaquat Ali Khan's Period and Religious Minorities 24 Creating New Constitution for Pakistan and Minorities 24 Ayub Khan's period and Minorities 25 Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's Period and Religious Minorities 26 Zia-ul-Haq's Period and Minorities 27 Restoration of Democratic Government and Minorities 28 Chapter 4: Rediscovering Jinnah's Inclusive Pakistan 31 Religious Minorities and Global Trends 31 Positive Developments since General Musharraf and Onwards 32 Political Participation 32 Minorities in Government 32 Education and/for Minorities 33 Celebrating Religious Festivals of Minorities 33 Recognizing the Role of Minorities in Nation Building 34 Judicial Activism and Minorities 34 Renovation of Worship Places 35 Speaking for Minorities 35 Safety of Religious Minorities 35 Economic -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

ORANGI PILOT PROJECT Institutions and Programs

822 PKOR03 ORANGI PILOT PROJECT Institutions and Programs 93rd QUARTERLY REPORT JAN,FEB, MAR'2003 Replication by LPP in Khanpur City is an important initiative. Laying of Trunk Sewer is in Progress. PLO1 NO. ST-4, SECTOR S/A, QASBA COLONY MANGHOPIR ROAD, KARACHI-75800 PHONE NOS. 6658021-6652297 Fax: 6665696, E-mail : [email protected] pk & [email protected] ORANGI PILOT PROJECT - Institutions and Programs Contents: Pages I. Introduction: 1-2 II. Receipts and Expenditure-Audited figure (1980 to 2002) 3 (OPP and OPP society) III. Receipts and Expenditure (2002-2003) Abstract of institutions 4 IV. Orangi Pilot Project - Research and Training Institute (OPP-RTI) 5-61 V. OPP-KHASDA Health and Family Planning Programme (KHASDA) 62-74 VI. Orangi Charitable Trust: Micro Enterprise Credit (OCT) 75-106 VII. Rural Development Trust (RDT) 107-114 I. INTRODUCTION: 1. Since April 1980 the following programs have evolved: Low Cost Sanitation-started in 1981 Low Cost Housing-started in 1986 Health & Family Planning-started in 1985 Women Entrepreneurs- started in 1984, later merged with Family Enterprise • Family Enterprise-started in 1987 Education- started in 1987 stopped in 1990. New program started in 1995. Social Forestry-started in 1990 stopped in 1997 Rural Development- started in 1992 2. The programs are autonomous with their own registered institutions, separate budgets, accounts and audits. The following independent institutions are now operating : i. OPP Society Council: It receives funds from INFAQ Foundation and distributes the funds according to the budgets to the Women Section (OCT), OPP-RTI, Khasda and RDT . For details of distribution see page 4. -

Name of Applicant Father's Name CNIC Date of Interview Test Centre

Name of Applicant Father's Name CNIC Date of InterTvieeswt Centre Address Syed Muhammad Shahrukh Shamim Syed Shahmim Akhter 42101-3921398-5 29/3/2018 Meteorological Complex, University Road, Karachi A-55, G/2, Block "L" North Nazimabad, Karachi Muhammad Saleem Muhammad Buksh 42101-9746141-1 29/3/2018 Meteorological Complex, University Road, Karachi Sukhia Goth Sector No.11/A, Gulzar-e-Hijri, Karachi Abdul Sami Palh Abdul Razzaque 45304-3239546-3 29/3/2018 Meteorological Complex, University Road, Karachi Shop No.07, Al-Shafi Book Store, Gulshan-e-Iqbal Block 11, Karachi Muhammad Talha Naseeb Muhammad Naseeb 42201-1478690-5 29/3/2018 Meteorological Complex, University Road, Karachi House No.F-26/2, Martin Quarters, Jahangir Road, Karachi Abdul Mannan Abdul Razzaque 45304-6976601-7 29/3/2018 Meteorological Complex, University Road, Karachi R-521, Model Village Block 11, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi Noman Ali Shamshad Ali 42301-4073366-9 29/3/2018 Meteorological Complex, University Road, Karachi House No.333, Block LL, Garden Road, Police Head Quarters, Karachi Arsalan Mirza Nayab Mirza 42201-1949167-9 29/3/2018 Meteorological Complex, University Road, Karachi Flat No.A-2, 1st Floor, Adeel Apartment, Block G, North Nazimabad, Karachi Muhammad Nabeel Khan Muhammad Sageer 42501-1368214-9 29/3/2018 Meteorological Complex, University Road, Karachi House No.F-23, Pakistan Tool Factory, Housing Colony Bin Qasim,Malir, Karachi Muhammad Asif Muhammad Aslam Baloch 42201-8444490-9 29/3/2018 Meteorological Complex, University Road, Karachi House No.1, Muhallah -

Rapid Need Assessment Report Monsoon Rains Karachi Division Th Th 24 – 27 August 2020

Rapid Need Assessment Report Monsoon Rains Karachi Division th th 24 – 27 August 2020 Prepared by: Health And Nutrition Development Society (HANDS) Address: Plot #158, Off M9 (Karachi – Hyderabad) Motorway, Gadap Road, Karachi, Pakistan Web: www.hands.org.pk Email: [email protected] Ph: (0092-21) 32120400-9 , +92-3461117771 1 | P a g e Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Background............................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Objectives ............................................................................................................... 3 2. Methodology .................................................................................................................. 4 Situation at Model Town after Heavy Rains ....................................................................... 4 Situation at Model Town after Heavy Rains ....................................................................... 4 3. Findings ......................................................................................................................... 5 3.1. District East............................................................................................................. 6 3.2. Major disaterous events in East district ................................................................... 6 3.3. District Malir ........................................................................................................... -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore