Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State: Uttar Pradesh Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Aligarh

State: Uttar Pradesh Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Aligarh 1.0 District Agriculture profile 1.1 Agro-Climatic/ Ecological Zone Agro-Ecological Sub Region(ICAR) Western plain zone Agro-Climatic Zone (Planning Commission) Upper Gangetic Plain Region Agro-Climatic Zone (NARP) UP-3 South-western Semi-arid Zone List all the districts falling the NARP Zone* (^ 50% area falling in the Firozabad, Aligarh, Hathras, Mathura, Mainpuri, Etah zone) Geographical coordinates of district headquarters Latitude Latitude Latitude (mt.) 27.55N 78.10E - Name and address of the concerned ZRS/ZARS/RARS/RRS/RRTTS - Mention the KVK located in the district with address Krishi Vigyan Kendra , Aligarh Name and address of the nearest Agromet Field Unit(AMFU,IMD)for CSAUAT, KANPUR agro advisories in the Zone 1.2 Rainfall Normal RF (mm) Normal Rainy Normal Onset Normal Cessation Days (Number) (Specify week and month) (Specify week and month) SW monsoon (June-sep) 579.5 49 3nd week of June 4th week of September Post monsoon (Oct-Dec) 25.3 10 Winter (Jan-March) 42.3 - - - Pre monsoon (Apr-May) 15.7 - - - Annual 662.8 49 1.3 Land use Geographical Cultivable Forest Land under Permanent Cultivable Land Barren and Current Other pattern of the area area area non- pastures wasteland under uncultivable fallows fallows district agricultural Misc.tree land (Latest use crops statistics) and groves Area in (000 371.3 321.3 2.6 40.6 1.7 6.5 0.3 5.0 5.4 5.0 ha) 1 1.4 Major Soils Area(‘000 hac) Percent(%) of total Deep, loamy soils 128.5 40% Deep, silty soils 73.8 23% Deep, fine soils 61.0 19% 1.5 Agricultural land use Area(‘000 ha.) Cropping intensity (%) Net sown area 304.0 169 % Area sown more than once 240.7 Gross cropped area 544.7 1.6 Irrigation Area(‘000 ha) Net irrigation area 302.1 Gross irrigated area 455.7 Rainfed area 1.9 Sources of irrigation(Gross Irr. -

Resettlement Plan IND: Uttar Pradesh Major District Roads Improvement

Resettlement Plan July 2015 IND: Uttar Pradesh Major District Roads Improvement Project Nanau-Dadau Road Prepared by Uttar Pradesh Public Works Department, Government of India for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 19 March 2015) Current unit - Indian rupee (Rs.) Rs1.00 = $0.0181438810 $1.00 = Rs.62.41 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AE – Assistant Engineer ASF -- Assistant Safeguards Focal APs - Affected Persons BPL – below poverty line BSR – Basic Schedule of Rates CPR – common property resources CSC – construction supervision consultant DC – district collector DPR – detailed project report EA – executing agency EE – executive engineer FGD – focus group discussion GOI – Government of India GRC – Grievance Redress Committee IA – implementing agency IP – indigenous peoples IR – involuntary resettlement LAA – Land Acquisition Act LAP – land acquisition plan NGO – nongovernment organization RFCT in – Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land LARR Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act RFCT in – Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land LARR Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (Amendment) (Ordinance) Ordinance. 2014 OBC – other backward castes RP - Resettlement Plan PD Resettl – Project Director PAPement Plan Project Affected Person PAF Project Affected Family PDF Project Displaced Family PDP Project Displaced Person PIU – project implementation unit R&R – resettlement and rehabilitation RF – resettlement framework RO – resettlement officer ROW – right-of-way RP – resettlement plan SC – scheduled caste SPS – ADB Safeguard Policy Statement, 2009 ST – scheduled tribe TOR – Terms of Reference UPPWD Uttar Pradesh Public Works Department VLC – Village Level Committee This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

Financial Needs and Resources O F Small

FINANCIAL NEEDS AND RESOURCES OF SMALL. INDUSTRIES IN ALIGARH DISTRICT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN COMMERCE By Oi^LDBlJB Under the Supervision of PROFESSOR Q. H. FAROOQUEE Dean, Faculty of Commerce FKCULTY OF COMMERCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (Uttar Pradesh, India) 1973 T1339 p 0, J y M |f,„.t.„^ ACKNOSSi^iOAJiiMSNT • *« • « •« a immmGnoH • •« « • ft i CHAmS 1 EOl£; OF miJU '^CaLE. m X aCONOSaC DIVEWKSHT OF ADVA«CSi) and 4km* mmm n PBOSLS?© AKB PROSPISCtS OF 55 uCAm M ium.A un R^Wwi^HQii to Qttm CHAH'iia III mm OF aHU uo fH&IR li^AQt QH iCObOi-'ElC to AuaAHH m^micf* QiAPm IV imnmnoHAi' muuc^s or cumt m i47 iriiujmi^ii in INUIA - CHAfTaa V FIKAKwlAi- tii^hm OF XNDUiffa^iS IH AUO/tfiH BI^miCT • A HAm JlMm CHAPTER VI dUfWiir OF Af^ OONaOl^lOlU m appendix 1 aoopi^U FOR omkinim VI INFORMATION ABOOT TOE imnKLAL UNITJ JllUATi&B xn auuahh. Bisuomumx • •• • •• ix m¥»pmmm - tn wFitim tills <*Fin»tsoi«3. ana aodourciia of aina-U laduatriea in a^^^S) District^, X have tsJ^tatXy bon6i'it-64 by my to varloito parte oJT India, where I opjporInanity ojT stuping apot tho Qyatm ol* iiorkiiig at^i I'inanein^ o£ smll fhia i«ave csq an into of I'inaneo mieh ^vo been i'acod in many part» ol* country and ar« aaora or oimiiar in their faa§nitud« in Aiifeet^ &iatri@t too* Moreover« lay intQr«at in the sub4oct hao tieiped m in underatandin^ btio probieiaa* The proaent mek ia m attempt to atudy the i»orking and ITinaneiai neoda and reaourooa ^ amali industries* In vriting thia titeaia I received vaiuabie heip and encourageoient -

Aligarh District, Uttar Pradesh

कᴂ द्रीय भूमम जऱ बो셍 ड जऱ संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण मंत्राऱय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Government of India Report on AQUIFER MAPPING AND GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN Aligarh District, Uttar Pradesh उत्तरीक्षेत्र , ऱखनऊ Northern Region, Lucknow For Restricted/ Authorized Official Use Only Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Central Ground Water Board Northern Region, Hkkjr ljdkj ty lalk/ku] unh fodkl vkSj xaxk laj{k.k ea=ky; dsUnzh; Hkwfety cksMZ mRrjh {ks= Interim Report AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN OF ALIGARH DISTRICT, UTTAR PRADESH By Dr. Seraj Khan Scientist “D’ Lucknow, April 2017 AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT OF ALIGARH DISTRICT, U.P. (A.A.P.: 2016-2017) By Dr Seraj Khan Scientist 'D' CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 OBJECTIVE 1 1.2 SCOPE OF STUDY 1 1.3 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 3 1.4 STUDY AREA 3 1.5 DEMOGRAPHY 4 1.6 DATA AVAILABILITY & DATA GAP ANALYSIS 5 1.7 URBAN AREA INDUSTRIES AND MINING ACTIVITIES 6 1.8 LAND USE, IRRIGATION AND CROPPING PATTERN 6 1.9 CLIMATE 13 1.10 GEOMORPHOLOGY 17 1.11 HYDROLOGY 19 1.12 SOIL CHARACTERISTICS 20 2.0 DATA COLLECTION, GENERATION, INTERPRETATION, INTEGRATION 22 AND AQUIFER MAPPING 2.1 HYDROGEOLOGY 22 2.1.1 Occurrence of Ground Water 22 2.1.2 Water Levels: 22 2.1.3 Change in Water Level Over the Year 28 2.1.4 Water Table 33 2.2 GROUND WATER QUALLIY 33 2.2.1 Results Of Basic Constituents 37 2.2.2 Results Of Heavy Metal 44 2.2.3 -

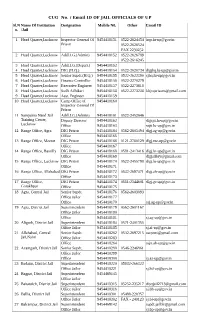

CUG No. / Email ID of JAIL OFFICIALS of up Sl.N Name of Institution Designation Mobile N0

CUG No. / Email ID OF JAIL OFFICIALS OF UP Sl.N Name Of Institution Designation Mobile N0. Other Email ID o. /Jail 1 Head Quarter,Lucknow Inspector General Of 9454418151 0522-2624454 [email protected] Prison 0522-2626524 FAX 2230252 2 Head Quarter,Lucknow Addl.I.G.(Admin) 9454418152 0522-2626789 0522-2616245 3 Head Quarter,Lucknow Addl.I.G.(Depart.) 9454418153 4 Head Quarter,Lucknow DIG (H.Q.) 9454418154 0522-2620734 [email protected] 5 Head Quarter,Lucknow Senior Supdt.(H.Q.) 9454418155 0522-2622390 [email protected] 6 Head Quarter,Lucknow Finance Controller 9454418156 0522-2270279 7 Head Quarter,Lucknow Executive Engineer 9454418157 0522-2273618 8 Head Quarter,Lucknow Sodh Adhikari 9454418158 0522-2273238 [email protected] 9 Head Quarter,Lucknow Asst. Engineer 9454418159 10 Head Quarter,Lucknow Camp Office of 9454418160 Inspector General Of Prison 11 Sampurna Nand Jail Addl.I.G.(Admin) 9454418161 0522-2452646 Training Center, Deputy Director 9454418162 [email protected] Lucknow Office 9454418163 [email protected] 12 Range Office, Agra DIG Prison 9454418164 0562-2605494 [email protected] Office 9454418165 13 Range Office, Meerut DIG Prison 9454418166 0121-2760129 [email protected] Office 9454418167 14 Range Office, Bareilly DIG Prison 9454418168 0581-2413416 [email protected] Office 9454418169 [email protected] 15 Range Office, Lucknow DIG Prison 9454418170 0522-2455798 [email protected] Office 9454418171 16 Range Office, Allahabad DIG Prison 9454418172 0532-2697471 [email protected] Office 9454418173 17 Range Office, DIG Prison 9454418174 0551-2344601 [email protected] Gorakhpur Office 9454418175 18 Agra, Central Jail Senior Supdt. -

Agency of Labor Resistance in Nineteenth Century India: Significance of Bulandshahr and F.S

Agency of Labor Resistance in Nineteenth Century India: Significance of Bulandshahr and F.S. Growse’s Account A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE in the School of Architecture and Interior Design of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2018 by Bhaswar Mallick B. Arch, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India, 2011. Committee: Rebecca Williamson, Ph.D. (Chair), and Arati Kanekar, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Hasty urbanization of non-metropolitan India has followed economic liberalization policies since the 1990s. To attract capital investments, such development has been compliant of globalization. However, agrarian protests and tribal Maoist insurgencies evidence resistance amidst concerns of internal colonialization. For the local building crafts, globalization has brought a ‘technological civilizing’. Facing technology that competes to replace rather than supplement labor, the resistance of masons and craftsmen has remained unheard, or marginalized. This is a legacy of colonialism. British historians, while glorifying ancient Indian architecture, argued to legitimize imperialism by portraying a decline. To deny the vitality of native architecture under colonialism, it was essential to marginalize the prevailing masons and craftsmen – a strain that later enabled portrayal of architects as professional experts in the modern world. Over the last few decades, members of the Subaltern Studies group, which originated in India, have critiqued post-colonial theory as being a vestige of and hostage to colonialism. Instead, they have prioritized the task of de-colonialization by reclaiming the history for the subaltern. A similar study in architecture is however lacking. -

Aligarh District, U.P

GROUND WATER BROCHURE ALIGARH DISTRICT, U.P. (A.A.P.: 2012-2013) By SAIDUL HAQ Scientist 'B' CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD NORTHERN REGION LUCKNOW, UP MAY 2013 GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF ALIGARH DISTRICT, U.P. (A.A.P.: 2012-2013) By SAIDUL HAQ Scientist 'B' CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. ALIGARH DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................6 1.1 Land Use 1.2 Studies / Activities Carried Out by CGWB 2.0 RAINFALL & CLIMATE ..................8 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY ..................9 3.1 Physiography 3.2 Drainage 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO ..................9 4.1 Geology 4.2 Ground Water Exploration 4.3 Hydro-geological Setup 4.4 Aquifer Parametres 4.5 Hydrogeology 4.6 Seasonal Fluctuation 4.7 Long Term Water Level Trends 4.8 Ground Water Resources 4.9 Ground Water Quality 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................21 5.1 Ground Water Development 5.2 Water Conservation & Artificial Recharge 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS ..................22 6.1 Water Logged Areas 6.2 Ground Water Polluted Area 7.0 AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY ..................23 8.0 AREA NOTIFIED BY CGWB / SGWA ..................23 9.0 RECOMMENDATIONS ..................23 PLATES: I. INDEX MAP OF ALIGARH DISTRICT, U.P. II. PRE-MONSOON DEPTH TO WATER MAP (MAY 2012), DISTRICT ALIGARH, U.P. III. POST-MONSOON DEPTH TO WATER MAP (NOVEMBER 2012), DISTRICT ALIGARH, U.P. IV. WATER LEVEL FLUCTUATION MAP (NOVEMBER 2012 – MAY 2012) V. WATER LEVEL DECADAL TREND ( 2003 – 2012) VI. GROUND WATER RESOURCE (AS ON 31.03.2009), DISTRICT ALIGARH, U.P. VII. HYDROGEOLOGICAL MAP OF ALIGARH DISTRICT, U.P. -

1 Village Kathera, Block Akrabad, Sasni to Nanau Road , Tehsil Koil

Format for Advertisement in Website Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Uttar Pradesh, as per following details: Fixed Fee / Security Estimated monthly Type of Minimum Dimension (in M.)/Area of Mode of Minimum Bid Sl. No Name of location Revenue District Type of RO Category Finance to be arranged by the applicant Deposit (Rs. Sales Potential # Site* the site (in Sq. M.). * Selection amount (Rs. In In Lakhs) Lakhs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 SC, SC CC-1, SC PH ST, ST CC-1, ST PH OBC, OBC CC- CC / DC / Estimated fund Estimated working Draw of Regular / 1, OBC PH CFS required for MS+HSD in Kls Frontage Depth Area capital requirement Lots / Rural development of for operation of RO Bidding infrastructure at RO OPEN, OPEN CC- 1, OPEN CC- 2,OPEN-PH Village Kathera, Block Akrabad, Sasni to Nanau Road , Draw of 1 Tehsil Koil, Dist Aligarh ALIGARH RURAL 90 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Dhansia, Block Jewar, Tehsil Jewar,On Jewar to GAUTAM BUDH Draw of 2 Khurja Road, dist GB Nagar NAGAR RURAL 160 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Dewarpur Pargana & Distt. Auraiya Bidhuna Auraiya Draw of 3 Road Block BHAGYANAGAR AURAIYA RURAL 150 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Village Kudarkot on Kudarkot Ruruganj Road, Block Draw of 4 AIRWAKATRA AURAIYA RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 5 Village Behta Block Saurikh on Saurikh to Vishun Garh Road KANNAUJ RURAL 100 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Lots 0 2 Draw of 6 Village Nadau, -

District Aligarh

DSR - ALIGARH District Aligarh 1. Introduction: Aligarh district is a district of Uttar Pradesh with its administrative headquarters located at Aligarh city. The city is famous as TalaNagri meaning "City of Locks" since there aremany lock industries in the city. Prior to 18th century Aligarh was popularly called by its former name i.e. Kol or Koil. But the name Kol covered both the city as well as the entire district. There are many theories regarding the origin of its name. According to some ancient texts, Kol or Koil might allude to caste, the name of a place or mountain,the name of a sage or demon. It is believed that the people, who came from Kampilya (aplace), founded the city and named it Kampilgarh. In course of time its name Kampilgarh changed to Koil and then Aligarh, the current name. During the past period Aligarh fort,the most prominent centre of attraction was also known as Koil fort. At that time Surajmal, a Jat ruler captured the Koil fort with help of Jai Singh from Jaipur and theMuslim army. He then renamed it as Ramgarh. Lastly, Najaf Khan, a Shia commander came to the place and occupied it and he changed the name of the fort to its present name of Aligarh. DISTRICT MAP SHOWING TEHSILS AND VILLAGES Page | 2 DSR - ALIGARH Page | 3 1. Overview of Mining Activity in the District: Brick Kiln Total Notice Notice issued Number Obtained EC not Applied District issued to by Regional of Brick EC obtained for EC shutdown Office kilns Aligarh 376 176 220 -- -- -- District Year Short termed Leases Revenue Generated Last 3 years Ordinary Soil Excavation Aligarh ( 2015, 2016, Rs. -

Republic of India Investment and Employment in Uttar Pradesh from Freight Corridor to Growth Corridor

Report No: ACS17034 . Republic of India Investment and Employment in Uttar Pradesh From Freight Corridor to Growth Corridor . March 2016 . GSU12 SOUTH ASIA . Document of the World Bank . Standard Disclaimer: . This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Copyright Statement: . The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA, telephone 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, http://www.copyright.com/. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA, fax 202-522-2422, e-mail [email protected]. -

MAP:Aligarh(Uttar Pradesh)

77°30'0"E 77°40'0"E 77°50'0"E 78°0'0"E 78°10'0"E 78°20'0"E 78°30'0"E 78°40'0"E ALIGARH DISTRICT GEOGRAPHICAL AREA (UTTAR PRADESH) 28°20'0"N KEY MAP BULANDSHAHR B U D GAUTAM BUDDHA NAGAR A U N BULANDSHAHR ± R CA-02 CA-01 GA KANSHIRAM NAGAR NA CA-05 HA PALWAL DD BU CA-04 M B TA U D AU A G U N CA-03 TO 28°10'0"N W MATHURA ARD S 28°10'0"N MAHAMAYA NAGAR KHUR T OW JA I R A A RDS T A H Total Population within the Geographical Area as per 2011 JEWA H C 36.73 Lacs.(Approx.) Pisava S Kazimabad D R *# *# TotalGeographicalArea(Sq.KMs) No.ChargeAreas R A K DEORAU RO K H 4051 5 Chandaus AD R a W a l UR *# i i R D lways O J A i v A O T Syaraul e RO IR Mahgaura r R *# A *# A Charge Areas Identification Tahsil Names T Nagla Padam D AT CA-01 Khair Gharvara -J *# Rampur Shahpur *# A Sumera Dariyapur Atrauli (MB) *# D Jawan Sikandpur Hardoi CA-02 Gabhana SAW *# PI A *# ! *# M O . D R R CA-03 Iglas Tappal Khandeha K 8 N AS 2 *# Umari A W CA-04 Koil *# G Yam M un *# ANJ a Jatari (NP) O GABHANA CA-05 Atrauli R S - iv Jamanka - A G Qasimpur Power House Colony (CT) T e R "/ Kasimpur Khushipur ! R RA r . -

Gonda Aligarh Kanpur Nagar Banda

1 \ , : ~ ;•, ~..".,' • ,'>--, MF Gonda IV! F Aligarh IV! F Kanpur Nagar Banda "I UTTAR PRADESH MALE REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH SURVEY 1995-1996 • The EVALUATION Project Carolina Population Center University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill CB #8120 University Square Chapel Hill, North Carolina 25716-3997 USA 1997 USAID Contract Number: DPE-3060-00-1054-00 I The EVALUATION Project / PERFORM ii CONTRIBUTORS Joseph deGraft-Johnson • Amy Ong Tsui Bates Buckner Kaushalendra K. Singh Ingrid Bou-Saada Christina Fowler Claire Viadro Julia Beamish Maria Khan In collaboration with Centre for Population and Development Studies, Hyderabad Indian Institute for Health Management Research, Jaipur Marketing and Research Organization, New Delhi Operations Research Group, New Delhi CONTENTS Page Tables , vii Figures '.' xii Acknowledgments .................................................... xv Executive Summary 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 5 Background of survey 5 Survey design and implementation .. : 6 Selection of rural villages and households 7 Selection of urban blocks and households 8 CHAPTER 2 RESPONDENT BACKGROUND CHARACTERISTICS 14 CHAPTER 3 KNOWLEDGE OF AND ATTITUDES TOWARD FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE ISSUES 17 Knowledge of the menstrual cycle 17 Knowledge of pregnancy and childbirth complications 18 Perception of fertility problems 19 Locus of control for pregnancy 20 Wife's ability to practice contraception 21 Importance of pregnancy prevention f9r husbands wanting no more children 23 Importance of pregnancy prevention for husbands wanting more children 24 CHAPTER