The Politics of Small Gestures Chances and Challenges for Contemporary Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finska Spelare I HV71

MEDIAGUIDE SÄSONGEN 2016/2017 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2016/2017 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2016/2017 SM-SLUTSPE INNEHÅLL 3 39 Kontaktpersoner Tränare 1971-2016 4 40 Truppen 16/17 Individuella klubbrekord 13 46 Lagledning 16/17 Tröjnummer 14 51 Nyförvärv och förluster 16/17 Tröjor i taket 16 62 Historia om HV71 Finska spelare i HV71 17 63 Historia om dom gamla klubbarna Utmärkelser/troféer 20 64 Poängligor 1979-2016 Lokala utmärkelser 27 65 Tabeller 1971-2016 Hockey Hall of fame 34 66 Flest spelade matcher HV-spelare i NHL-draften 37 69 Flest spelade slutspelsmatcher HV-spelare i de stora turneringarna MEDIAGUIDE SÄSONGEN 2016/2017 2 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2016/2017 SM-SLUTSPE KONTAKTPERSONER ORDFÖRANDE Sten-Åke Karlsson, [email protected], 070-698 42 15 KLUBBDIREKTÖR Agne Bengtsson, [email protected], 036-299 71 18 GENERAL MANAGER SPORT Peter Ekelund, [email protected], 036-299 71 11 SPORTCHEF Johan Hult, [email protected], 036-299 71 14 ASS. SPORTCHEF Johan Davidsson, [email protected], 036-299 71 29 MARKNADSCHEF Johan Skogeryd, [email protected], 036-299 71 04 PRESSANSVARIG/ACKREDITERING Johan Freijd, [email protected], 036-299 71 15 BILJETTER Robert Linge, [email protected], 036-299 71 00 ARENACHEF Bengt Halvardsson, [email protected], 0733-27 67 99 HV71, Kinnarps Arena, 554 54 JÖNKÖPING www.hv71.se | [email protected] twitter.com/hv71 | facebook.com/hv71 | instagram.com/hv71 | youtube.com/hv71 MEDIAGUIDE SÄSONGEN 2016/2017 3 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2016/2017 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2016/2017 SM-SLUTSPE TRUPPEN 16/17 MÅLVAKTER 30 LINUS SÖDERSTRÖM FÖDD 1996-08-23 A-SÄSONGER I HV71 NY FÖDELSEORT STOCKHOLM SHL-MATCHER I HV71 - LÄNGD 195 CM SLUTSPELSMA. -

Olympic Ice Hockey Media Guide T Orino 2006

Olympic Ice Hockey Media Guide 2006 Torino International Ice Hockey Federation The XX Olympic Winter Games Torino 2006 Players named to 4th Olympics Czech Republic: Dominik Hasek, G, 1988, 1998, 2002 Robert Lang, F, 1992, 1998, 2002 Finland: Teppo Numminen, D, 1988, 1998, 2002 Photo: Al Behrman, Associated Press Teemu Selanne, F, 1992, 1998, 2002 Sami Kapanen, F, 1994, 1998, 2002 Jere Lehtinen, F, 1994, 1998, 2002 Germany: U.S. defenseman Chris Chelios Jan Benda, D/F, 1994, 1998, 2002 Stefan Ustorf, F, 1994, 1998, 2002 Italy: Lucio Topatigh, F, 1992, 1994, 1998 Russia: Darius Kasparaitis, D, 1992, 1998, 2002 Alexei Zhamnov, F,1992, 1998, 2002* Sweden: Jorgen Jonsson, F, 1994, 1998, 2002 USA: Stamp: Swedish Post, Chris Chelios, D, 1984, 1998, 2002 Photo: Gary Hershorn, Reuters Keith Tkachuk, F, 1992, 1998, 2002 *named to initial roster, but injured Did you know? Did you know? Fourteen players who were named to their Olympic rosters on December 22 will, The only time an Olympic gold medal was decided in a game winning shot barring injuries, participate in their fourth Olympic ice hockey tournament. competition (“shootout”) was in 1994 in Lillehammer. A brave Team Canada, This group of international hockey veterans is lead by 44-year old U.S. defenseman comprised mostly of minor leaguers and amateurs, held a 2 – 1 lead until 18.11 Chris Chelios who will also set another Olympic record, becoming the first to of the third period when Sweden scored a power-play goal to even it up. play in an Olympic hockey tournament 22 years after taking part in his first, Canada also had a 2-0 lead in the shootout competition, but with the score 1984 in Sarajevo. -

New Practices, New Pedagogies

INNOVATIONS IN ART AND DESIGN NEW PRACTICES NEW PEDAGOGIES a reader EDITED BY MALCOLM MILES SWETS & ZEITLINGER / TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP 2004 Printed in Copyright © 2004 …… All rights reserved. No part of this publication of the information contained herein may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, without written prior permission from the publishers. Although all care is taken to ensure the integrity and quality of this publication and the information herein, no responsibility is assumed by the publishers nor the authors for any damage to properly or persons as a result of operation or use of this publication and/or the information contained herein. www ISBN ISSN The European League of Institutes of the Arts - ELIA - is an independent organisation of approximately 350 major arts education and training institutions representing the subject disciplines of Architecture, Dance, Design, Media Arts, Fine Art, Music and Theatre from over 45 countries. ELIA represents deans, directors, administrators, artists, teachers and students in the arts in Europe. ELIA is very grateful for support from, among others, The European Community for the support in the budget line 'Support to organisations who promote European culture' and the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science Published by SWETS & ZEITLINGER / TAYLOR & FRANCIS GROUP 2004 Supported by the European Commission, Socrates Thematic Network ‘Innovation in higher arts education -

Swedish Olympic Team PYEONGCHANG 2018

Swedish Olympic Team PYEONGCHANG 2018 MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, PYEONGCHANG 2018 3 MEDIA GUIDE SWEDEN This Booklet, presented and published by the Swedish Olympic Committee is intended to assist members of the media at the Games of the XXXII Olympiad. Information is of January 2018. For late changes in the team, please see www.sok.se. Location In northern Europe, on the east side of the Scandi- navian Peninsula, with coastline on the North and Baltic seas and the Gulf of Bothnia. Neighbours Norway on the East. Mountains along Northwest border cover 25 per cent of Sweden. Flat or rolling terrain covers central and southern areas which includes several large lakes. Official name: Konungariket Sverige (Kingdom of Sweden). Area: 447 435 km2 (173 732 sq. miles). Rank in the world: 57. Population: 10 093 734 Capital: Stockholm Form of government: Constitutional monarchy and parliamentary state with one legislative house (Parliament with 349 seats). Current constitution force since January 1st, 1975. Chief of state: King Carl XVI Gustaf, since 1973. Head of government: Prime Minister Stefan Löfven, since 2014. Official language: Swedish. Monetary unit: 1 Swedish krona (SEK) = 100 öre. (Valuation January 2018). 1 USD= 8,17 SEK, 1 EUR= 9,83 SEK. MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, PYEONGCHANG 2018 4 ANSVARIG UTGIVARE Lars Markusson, + 46 (0) 70 568 90 31, [email protected] ADRESS Sveriges Olympiska Kommitté, Olympiastadion, Sofiatornet, 114 33 Stockholm TEL 08-402 68 00 www.sok.se LAYOUT Linda Sandgren, SOK TRYCK Elanders 2018 MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, PYEONGCHANG 2018 5 CONTENT SWEDISH OLYMPIC COMMITTEE 6 INTERNATIONAL OLYMPIC MOVEMENT 8 SWEDEN AND THE OLYMPIC GAMES 9 SWEDISH MEDALLISTS 10 CDM:S AND FLAG BEARERS 18 SWEDEN AT PREVIOUS WINTER GAMES 19 OLYMPIC VENUES 20 COMPETITION SCHEDULE 22 SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM 24 MEDIA GUIDE - SWEDISH OLYMPIC TEAM, PYEONGCHANG 2018 6 SWEDISH OLYMPIC COMMITTEE The Swedish Olympic Committee, SOC, is the supreme authority of Sweden in all Olym- pic matters. -

Mediaguide 2019/2020

MEDIAGUIDE 2019/2020 är sammanställd av Johan Freijd, Martin Unander och med stor hjälp av Johan Nyberg. Statistik från shl.se, swehockey.se och eliteprospects.com Med reservation för eventuella förändringar, tryckfel och faktafel. Mediaguide_1920_omslag.indd 1 2019-08-27 11:36 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2019/2020 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2019/2020 INNEHÅLL KONTAKTPERSONER 3 38 Kontaktpersoner Tränare 1971-2019 4 40 Truppen 19/20 Individuella klubbrekord 13 46 Lagledning 19/20 Tröjnummer 14 50 Nyförvärv och förluster 19/20 Pensionerade nummer 16 64 Historia om HV71 Finska spelare i HV71 17 65 Historia om dom gamla klubbarna Utmärkelser/troféer 20 66 Poängligor 1979-2019 Lokala utmärkelser 27 67 Tabeller 1971-2019 Hockey Hall of fame 34 68 Flest spelade matcher HV-spelare i NHL-draften 36 69 Flest spelade slutspelsmatcher HV-spelare i de stora turneringarna 2 HV71 MEDIAGUIDE 2019/2020 INNEHÅLL KONTAKTPERSONER ORDFÖRANDE Sten-Åke Karlsson | [email protected] | 070-698 42 15 KLUBBDIREKTÖR Agne Bengtsson | [email protected] | 036-299 71 18 GENERAL MANAGER SPORT Peter Ekelund | [email protected] | 036-299 71 11 SPORTCHEF Johan Hult | [email protected] | 036-299 71 14 ASS. SPORTCHEF Johan Davidsson | [email protected] | 036-299 71 29 PRESSANSVARIG / ACKREDITERING Johan Freijd | [email protected] | 036-299 71 15 BILJETTER Robert Linge | [email protected] | 036-299 71 00 ARENACHEF Mikael Sundelius | [email protected] | 036-299 71 21 HV71 | Kinnarps Arena | 554 54 JÖNKÖPING www.hv71.se | [email protected] twitter.com/hv71 | facebook.com/hv71 -

Finnish Studies

JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES Volume 16 Number 2 May 2013 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458 (P.O. Box 2146), Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TEXAS 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1402; Fax 1.936.294.1408 SUBSCRIPTIONS, ADVERTISING, AND INQUIRIES Contact Business Office (see above & below). EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki; [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Associate Editor, Sam Houston State University; [email protected] Hilary Joy Virtanen, Assistant Editor, University of Wisconsin; [email protected] Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University; [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University, Toronto Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University, New York Anselm Hollo, Professor, Naropa Institute, Boulder, Colorado Richard Impola, Professor Emeritus, New Paltz, New York Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, Department of -

Babacar Kamara Blev SM:S Bästa Boxare Thomas Johansson Tillbaka I Djurgården

Lokaltidningen Mitt i Vasastan - Tisdag 2 maj 2006 27 Sportredaktör: Irmi Persson 550 550 67 SPORT fax: 550 550 77, 550 551 44 e-post: [email protected] Mika – en 08:a i exil Stockholmaren och HV71-stjärnan Hannula längtar hem och till hockey-VM. Det är inte lätt att hitta ! Nio olika klubbar stockholmare i VM-truppen. Namn: Mika Hannula. Alla lever numera i ”exil”, Ålder: 27 år. utomlands eller på andra Bor: Jönköping. orter i Sverige. Född: Huddinge. OS-spelaren Mika Hannu- Klubbar: TPS Åbo, Djurgården, la lämnade stan för länge AIK J20, Djurgården J20, Lukko Rauma J20, Lidingö HC, Ham- sedan – eftersom Stock- marby, Malmö IF, Houston holmssklubbarna sällan Aeros, Malmö IF, HV71. släppte fram egna talanger. Aktuell: Tas ut i VM-truppen som presenteras i dag tisdag. I dag tisdag presenteras stommen av truppen till VM i Lettland som börjar på lördag. Den lär bli kliniskt att spela seniorhockey tvingade fri från spelare från Djurgården – därför iväg honom till Lidingö huvudstadens enda elitserielag. HC. Till Malmö, där han fick sitt Ingen röd-blå-gul spelade gångna genombrott, kom han som 20- veckoslutets förturnering, LG åring. Hockey games i Globen. Däremot Resten är en framgångsrik elit- innehöll truppen en handfull 08:or serie- och landslagskarriär. som spelar i klubbar på andra orter. – Jo, nu kan jag känna att det var Stockholmsishockeyn saknar i nyttigt att komma bort från Stock- dag allt – ekonomi, stjärnor och holm. Malmö, det handlade om att publik. acceptera läget, ta chansen. HV71-stjärnan Hannula nöjer Han erkänner utan omsvep att sig med att nicka lätt moloket när han saknar hemstaden. -

Artistic Research Methodology

15 Artistic Research Methodology argues for artistic research as a context-aware and historical ARTISTIC RESEARCHMETHODOLOGY process that works inside-in, beginning and ending with acts committed within an artistic practice. An artistic researcher has three intertwined tasks. First, she needs to develop and perfect her own artistic skills, vision and conceptual thinking. This happens by developing a vocabulary for not only making but also writing and speaking about art. Second, an artistic researcher has to contribute to academia and the “invisible colleges” around the world by proposing an argument in the form of a thesis, a narrative; and in so doing helping to build a community of artistic research and the bodies of knowledge these communities rely on. Third, she must communicate with practicing artists and the larger public, performing what one could call “audience education.” There is no way of being an engaged and committed partner in a community without taking sides, without getting entangled in issues of power. Consequently, the methodology of artistic research has to be responsive both to the require- ments of the practice and the traditions of science. Here the embedded nature of the knowl- edge produced through artistic research becomes evident. Artistic Research Methodology is essential reading for university courses in art, art education, media and social sciences. Mika Hannula (Ph.D., University of Turku, Finland) is a former rector of the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki, Finland, and is Professor of Visual Arts at the University of Gothenburg, Swe- den. He curates contemporary art exhibitions across Europe and consults for a contemporary art gallery in Helsinki. -

Careers Are Remembered by Olympic Success

Publisher: International Ice Hockey Federation, Editor-in-Chief: Jan-Ake Edvinsson Editors: Kimmo Leinonen, Szymon Szemberg Layout: Szymon Szemberg, Assistant Editor: Jenny Wiedeke September 2003 - Vol 7 - No 4 Edward Groeger Edward Photo: HOME OPENER. IIHF President René Fasel (left) is all smiles as IOC President Jacques Rogge drops the puck for the inaugural face-off between Fasel and the Mayor of Zurich, Elmar Ledergerber. The August 21 ceremony, which officially inaugurated the new IIHF offices, is witnessed by Christian Huber, the President Councillor of the Government of Kanton Zurich, and by Juan Antonio Samaranch, Lifetime IOC Honorary President. See more on the inauguration on page 11. Careers are remembered by Olympic success The 115th IOC Session in Prague, Czech Republic on July 1 was Olympic Winter Games. Indeed, the Olympics - and the Olympic ice hockey tourna- thrilling for sports fans and ice hockey fans in particular. And just ment - have an inner strength that goes beyond individual participation. like in hockey, there could only be one winner. Out of three very good bids for the 2010 Olympic Winter Games, Vancouver came out Heroes are made in the Olympics, regardless of what merit you bring with you coming into the Games. On August 11, a shock hit the world of hockey when Herb victorious. Brooks died in a car accident. In February 1980 a virtually unknown Brooks brought a group of college no-names to Lake Placid and proved that miracles can happen. II As president of the RENÉ FASEL EDITORIAL International Ice Hockey II None of his players became superstars and Brooks never won a championship in Federation, I cannot deny that going to Canada with an Olympic ice hockey tourna- the pro-ranks after Lake Placid, but their careers will always be measured by what ment presents a huge opportunity for our sport. -

Verksamhetsberättelse 07/08

Verksamhetsberättelse 07/08 Verksamhetsberättelse 07/08 Innehållsförteckning Styrelse 4 Ordförande 5 Klubbdirektör 6 Ekonomi 8 Marknad 9 A-lagsverksamhet 10 Tabellen & statistik 07/08 11 Antal spelade matcher för HV71 12 tom 07/08 Poängligan för HV71 07/08 14 HV-spelare i landslagen 07/08 15 Ungdom & Utveckling 16 Ungdomsstyrelse 17 HV71 Fastighets AB 18 ArenaService 18 Veteranerna 19 Utmärkelser 20 Årsredovisning för räkenskapsåret 07/08 21 Svenska Mästare 2008 i bilder 42 Verksamhetsberättelse 07/08 Styrelse 07/08 Styrelse Hans-Göran Frick Ordförande Thomas Lindster Ledamot Stefan Falk Ledamot Tommy Mårdskog Ledamot Per-Arne Andersson Ledamot Per Rodert Ledamot Sofia Axelsson Ledamot HV71 Fastighets AB Sten-Åke Karlsson Ordförande Tommy Fritz Ledamot (VD) Per-Arne Andersson Ledamot Arne Davidsson Ledamot Owe Jungåker Ledamot Ungdomsstyrelse Per Johansson Ordförande Kenneth Halvardsson Ledamot Jan Lindberg Ledamot Ulf Rahm Ledamot Magnus Ljungqvist Ledamot Lennart Lindeberg Ledamot Veteranstyrelse Carl-Olof Sandberg Ordförande Håkan Rosén Ledamot Christer Ljungberg Ledamot Thomas Lundqvist Ledamot Toni Fernström Ledamot Valberedning Jan-Erik Persson Ordförande Lena Nero Ledamot Toni Fernström Ledamot Tommy Hjalmarsson Ledamot - 4 - Verksamhetsberättelse 07/08 SM-guld Vi stack ut hakan och uppfattades av många som ”lite kaxiga” och tillkommit som en ny spännande och positiv företeelse, ett inträde för satte tre högt ställda mål inför säsongen; serieseger, kvalificering HV71 i NT (Nordic Trophy) en träningsturnering med internationellt till CHL (Champions Hockey League) och att gå till SM-final. Vi inslag som har potential att kunna utvecklas. Därtill har en till delar lyckades fullt ut och vann dessutom SM-finalen och ny rysk liga KHL (Kontinental Hockey League) sett kunde notera det tredje vunna SM-guldet i förenin- dagens ljus med ambitioner och ekonomiska muskler gens historia – fantastiskt! som känns såväl som ett hot för den inhemska hock- eyn som en möjlighet i ett internationellt perspektiv. -

Jyri Backman Ishockeyns Amerikanisering

MALMÖ STUDIES IN SPORT SCIENCES NR 27 NR SCIENCES SPORT IN STUDIES MALMÖ JYRI BACKMAN ISHOCKEYNS AMERIKANISERING En studie av svensk och finsk elitishockey ISHOCKEYNS AMERIKANISERING: EN STUDIE AV SVENSK OCH FINSK ELITISHOCKEY Malmö Studies in Sport Sciences Nr 27 © Copyright Jyri Backman, 2018 Layout omslag: Anneli Holmberg ISBN 978-91-7104-902-5 (tryckt) ISBN 978-91-7104-903-2 (pdf) ISSN Malmö Studies in Sport Sciences 1652-3180 Holmbergs, Malmö 2018 JYRI BACKMAN ISHOCKEYNS AMERIKANISERING En studie av svensk och finsk elitishockey Malmö universitet, 2018 Idrottsvetenskap Publikationen finns även elektroniskt på: https://muep.mau.se/handle/2043/24404 Äidille ja Isän muistolle Erkki Sakari Kuoppala 1935–2018 Till Mor och till minne av min Far Erkki Sakari Kuoppala 1935–2018 INNEHÅLL UPPVÄRMNING ............................................................. 9 Tabell- och figurindex ............................................................11 Förord .................................................................................13 Förkortningar .......................................................................17 FÖRSTA PERIODEN....................................................... 21 Nedsläpp ............................................................................23 Syfte och frågeställningar .................................................28 Disposition ......................................................................29 Tidigare forskning om svensk och finsk ishockey ..................30 Historisk bakgrund: Sverige och -

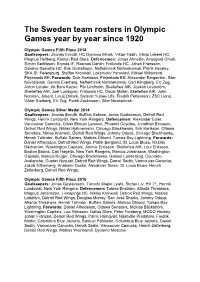

The Sweden Team Rosters in Olympic Games Year by Year Since 1920

The Sweden team rosters in Olympic Games year by year since 1920 Olympic Games Fifth Place 2018 Goalkeepers: Jhonas Enroth, HC Dynamo Minsk, Viktor Fasth, Växjö Lakers HC, Magnus Hellberg, Kunlun Red Stars. Defencemen: Jonas Ahnelöv, Avangard Omsk, Simon Bertilsson, Brynäs IF, Rasmus Dahlin, Frölunda HC, Johan Fransson, Genève-Servette HC, Erik Gustafsson, Neftekhimik Nizhnekamsk, Patrik Hersley, SKA St. Petersburg, Staffan Kronwall, Lokomotiv Yaroslavl, Mikael Wikstrand, Färjestads BK. Forwards: Dick Axelsson, Färjestads BK, Alexander Bergström, Sibir Novosibirsk, Dennis Everberg, Neftekhimik Nizhnekamsk, Carl Klingberg, EV Zug, Anton Lander, Ak Bars Kazan, Pär Lindholm, Skellefteå AIK, Joakim Lindström, Skellefteå AIK, Joel Lundqvist, Frölunda HC, Oscar Möller, Skellefteå AIK, John Norman, Jokerit, Linus Omark, Salavat Yulaev Ufa, Fredrik Pettersson, ZSC Lions, Viktor Stålberg, EV Zug, Patrik Zackrisson, Sibir Novosibirsk. Olympic Games Silver Medal 2014 Goalkeepers: Jhonas Enroth, Buffalo Sabres, Jonas Gustavsson, Detroit Red Wings, Henrik Lundqvist, New York Rangers. Defencemen: Alexander Edler, Vancouver Canucks, Oliver Ekman Larsson, Phoenix Coyotes, Jonathan Ericsson, Detroit Red Wings, Niklas Hjalmarsson, Chicago Blackhawks, Erik Karlsson, Ottawa Senators, Niklas Kronwall, Detroit Red Wings, Johnny Oduya, Chicago Blackhawks, Henrik Tallinder, Buffalo Sabres, Mattias Öhlund, Tampa Bay Lightning. Forwards: Daniel Alfredsson, Detroit Red Wings, Patrik Berglund, St. Louis Blues, Nicklas Bäckström, Washington Capitals, Jimmie Ericsson, Skellefteå AIK, Loui Eriksson, Boston Bruins, Carl Hagelin, New York Rangers, Marcus Johansson, Washington Capitals, Marcus Krüger, Chicago Blackhawks, Gabriel Landeskog, Colorado Avalanche, Gustav Nyquist, Detroit Red Wings, Daniel Sedin, Vancouver Canucks, Jakob Silfverberg, Anaheim Ducks, Alexander Steen, St. Loius Blues, Henrik Zetterberg, Detroit Red Wings. Olympic Games Fifth Place 2010 Goalkeepers: Jonas Gustavsson, Toronto Maple Leafs, Stefan Liv, HV 71, Henrik Lundqvist, New York Rangers.