Remotely-Piloted Aircraft Systems and Modern Warfare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3Rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria

The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Colantoni, C., and J. A. Ur. 2011. The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria. Iraq 73:21-69 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:5342153 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA VOLUME LXXIII • 2011 CONTENTS Editorial iii Obituaries: Dr Donny George Youkhanna, Mrs Rachel Maxwell-Hyslop v Jason Ur, Philip Karsgaard and Joan Oates: The spatial dimensions of early Mesopotamian urbanism: The Tell Brak suburban survey, 2003–2006 1 Carlo Colantoni and Jason Ur: The architecture and pottery of a late third-millennium residential quarter at Tell Hamoukar, north-eastern Syria 21 David Kertai: Kalæu’s palaces of war and peace: Palace architecture at Nimrud in the ninth century bc 71 Joshua Jeffers: Fifth-campaign reliefs in Sennacherib’s “Palace Without Rival” at Nineveh 87 M. P. Streck and N. Wasserman: Dialogues and riddles: Three Old Babylonian wisdom texts 117 Grégory Chambon and Eleanor Robson: Untouchable or unrepeatable? The upper end of the Old Babylonian metrological systems for capacity -

3Rd Millennium Sales

Taking Sales to a Higher Level 3rd Millennium Sales Mercuri International’s 3rd Millennium Sales Concept will help you pick and practice the skills required to transform yourself into a future proof sales professional. Why the Need to Adapt? Quite simply because the digital world has drastically increased the information available to your customers. In turn, customers progress through significantly more of their ’buying journey’ before even meeting a sales person. This ’Digital Maturity’ also becomes more prevelant across various industries: Digital Maturity* Across Various Industries IT TOURISM RETAIL BANKING DISTRIBUTION FAST MOVING CONSUMER GOODS INDUSTRY AND SERVICES HEALTHCARE PUBLIC SECTOR RETAIL HANDICRAFT AGRICULTURE BUILDING *Adapted from the article ‘Digital Advantage’ by Capgemini Consulting & MIT Sloan Management. Average Percentage of Buying Journey before engaging with a Sales Person Future proofing the Consider these statements: Sales Professional The sales profession has evolved with the times to meet the 57% of the customer buying journey is changing needs of every passing generation. It is now time, for completed digitally before the first serious another wave of change. The difference - this is not a gradual engagement with a sales person, said evolution. This is transformation. Even as technology transforms CEB & Google in their 2011 study - Digital the way Customers buy, it also calls for sellers to transform the Evolution in B2B Marketing. (Since revised way they sell. Those who heed this call and are willing to trans- to 67% in 2014). form, will ride this wave, taking their careers and organizations to greater heights. As Alvin Tofler predicted many years ago “The Research shows that the 80% of the illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read sales community using social media is and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn”. -

BIENNIAL REVIEW Drug-Free Schools and Campuses Calendar Year 2018 – Calendar Year 2019 University of Nebraska at Kearney 2504 9Th Ave, Kearney, NE 68849

BIENNIAL REVIEW Drug-Free Schools and Campuses Calendar Year 2018 – Calendar Year 2019 University of Nebraska at Kearney 2504 9th Ave, Kearney, NE 68849 Prepared by Biennial Review Committee George Holman, Associate Dean for Student Affairs Wendy Schardt, Director of Student Health & Counseling Dave Roberts, Assistant Dean for Student Affairs Kiphany Hof, Associate Director of UNK Counseling Amanda Dabney, Wellness Promotions and Prevention Coordinator Dawn Adams, Lieutenant, UNK Police Michelle Holman, Clery Coordinator, UNK Police August 2020 Report Overview I. University of Nebraska at Kearney Wellness Programming – Mission Statement Pg. 2 II. Alcohol & Other Drug Policy (AOD) Pg. 2 - AOD Policy Application & Enforcement - University Sanctions and Student Success Center Program Requirements - Policy Distribution Procedures - Student Violations of AOD Policy During Reporting Period - Considerations Regarding Policy & Student Violations III. Student Success Center – Counseling Services Pg. 5 IV. Programming During Reporting Period - Student Success Center - Programming - Professional Development V. Health Education Office Programming Strengths & Challenges Pg. 5 - Program Strengths - Program Challenges VI. Recommendations for Revision & Improvement Pg. 8 VII. Appendix Pg. 8 1 I. University of Nebraska Kearney Wellness Programming – Mission Statement The Health Education Office works to Engage, Educate, and Empower students on how to make wise choices when it comes to alcohol & tobacco use, mental health wellbeing, and healthy living. Their mission is to alleviate persistence problems caused by alcohol abuse by better educating the University of Nebraska at Kearney (UNK) students on the dangers of high-risk drinking, creating positive changes in students’ attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors regarding alcohol use. The office works to ensure that prevention messages, enforcement efforts, educational materials, alternative resources, assessments, and analysis, are all universally streamlined. -

11. Cultural Contacts and Mobility Between the South Central Mediterranean and the Aegean During the Second Half of the 3Rd Millennium BC

CULTURAL CONTACTS AND MOBILITY 243 11. Cultural contacts and mobility between the south central Mediterranean and the Aegean during the second half of the 3rd millennium BC ALBERTO CAZZELLA, ANTHONY PACE AND GIULIA RECCHIA Abstract One of the effects of the reconfiguration of world prehistoric chronolo- gies as a result of radiocarbon dating has been the questioning of hith- erto established frameworks of connectivity and the movement of peo- ple, materials and ideas in prehistory. This contribution revisits issues of connectivity between the south-central Mediterranean region and the Aegean during the Early Bronze Age. This short study highlights the need for scholars to re-examine connectivity using, as an example, diagnostic archaeological evidence of intra-regional links between South Italy, Sic- ily and Malta and the Aegean, that was not affected by carbon dating. The paper suggests that while broader regional patterns of connectivity may have benefited from revised chronologies of world prehistory, mi- cro-regional cultural links may require new explanations of crossings and the evident movement of commodities by land and by sea. Radiocarbon dating and the re-examination of diffusionist thinking during the post World War II decades raised several questions concern- ing the nature of cultural contact across the Mediterranean during late prehistory. Seminal work by Colin Renfrew (1973) on the effects of new chronologies, served to emphasise the discordant cultural links that older dating frameworks had suggested. Hitherto established theories of hu- man mobility involving extensive geographic areas, as well as links be- tween small communities of the Mediterranean, also came under close 244 ALBERTO CAZZELLA, ANTHONY PACE AND GIULIA RECCHIA scrutiny and, in many cases, were abandoned altogether. -

The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3Rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria

The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Colantoni, C., and J. A. Ur. 2011. The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria. Iraq 73:21-69 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:5342153 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA VOLUME LXXIII • 2011 CONTENTS Editorial iii Obituaries: Dr Donny George Youkhanna, Mrs Rachel Maxwell-Hyslop v Jason Ur, Philip Karsgaard and Joan Oates: The spatial dimensions of early Mesopotamian urbanism: The Tell Brak suburban survey, 2003–2006 1 Carlo Colantoni and Jason Ur: The architecture and pottery of a late third-millennium residential quarter at Tell Hamoukar, north-eastern Syria 21 David Kertai: Kalæu’s palaces of war and peace: Palace architecture at Nimrud in the ninth century bc 71 Joshua Jeffers: Fifth-campaign reliefs in Sennacherib’s “Palace Without Rival” at Nineveh 87 M. P. Streck and N. Wasserman: Dialogues and riddles: Three Old Babylonian wisdom texts 117 Grégory Chambon and Eleanor Robson: Untouchable or unrepeatable? The upper end of the Old Babylonian metrological systems for capacity -

Analyzing the Case of Kenya Airways by Anette Mogaka

GLOBALIZATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY: ANALYZING THE CASE OF KENYA AIRWAYS BY ANETTE MOGAKA UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY - AFRICA SPRING 2018 GLOBALIZATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY: ANALYZING THE CASE OF KENYA AIRWAYS BY ANETTE MOGAKA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL STUDIES (SHSS) IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS DEGREE IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY - AFRICA SUMMER 2018 STUDENT DECLARATION I declare that this is my original work and has not been presented to any other college, university or other institution of higher learning other than United States International University Africa Signature: ……………………… Date: ………………………… Anette Mogaka (651006) This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as the appointed supervisor Signature: …………………. Date: ……………………… Maurice Mashiwa Signature: …………………. Date: ……………………… Prof. Angelina Kioko Dean, School of Humanities and Social Sciences Signature: …………………. Date: ……………………… Amb. Prof. Ruthie C. Rono, HSC Deputy Vice Chancellor Academic and Student Affairs. ii COPYRIGHT This thesis is protected by copyright. Reproduction, reprinting or photocopying in physical or electronic form are prohibited without permission from the author © Anette Mogaka, 2018 iii ABSTRACT The main objective of this study was to examine how globalization had affected the development of the airline industry by using Kenya Airways as a case study. The specific objectives included the following: To examine the positive impact of globalization on the development of Kenya Airways; To examine the negative impact of globalization on the development of Kenya Airways; To examine the effect of globalization on Kenya Airways market expansion strategies. -

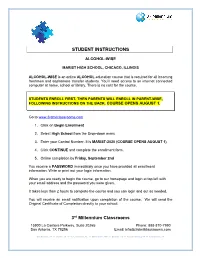

STUDENT INSTRUCTIONS 3Rd Millennium Classrooms

STUDENT INSTRUCTIONS ALCOHOL-WISE MARIST HIGH SCHOOL, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS ALCOHOL-WISE is an online ALCOHOL education course that is required for all incoming freshmen and sophomore transfer students. You’ll need access to an internet connected computer at home, school or library. There is no cost for the course. STUDENTS ENROLL FIRST. THEN PARENTS WILL ENROLL IN PARENT-WISE, FOLLOWING INSTRUCTIONS ON THE BACK. COURSE OPENS AUGUST 1. Go to www.3rdmilclassrooms.com 1. Click on Begin Enrollment 2. Select High School from the Drop-down menu 3. Enter your Control Number. It is MARIST-2020 (COURSE OPENS AUGUST 1) 4. Click CONTINUE and complete the enrollment form. 5. Online completion by Friday, September 2nd You receive a PASSWORD immediately once you have provided all enrollment information. Write or print out your login information. When you are ready to begin the course, go to our homepage and login at top left with your email address and the password you were given. It takes less than 2 hours to complete the course and you can login and out as needed. You will receive an email notification upon completion of the course. We will send the Original Certificate of Completion directly to your school. rd 3 Millennium Classrooms 15900 La Cantera Parkway, Suite 20265 Phone: 888-810-7990 San Antonio, TX 78256 Email: [email protected] San Antonio, TX <> Austin, TX <> Ft. Lauderdale, FL <> Minneapolis, MN <> Boulder, CO <> Fredericksburg, VA <> Sacramento, CA PARENT WISE INSTRUCTIONS MARIST HIGH SCHOOL, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS PARENT-WISE is a FREE online alcohol education course designed for Marist parents. -

History – 2000 Thru 2014

This Time in History NOTABLE EVENTS IN WORLD/U.S. HISTORY - CONTINUED 2000 - 2014 2008 Oil prices in the U.S. hit a record $147 per barrel IMMANUEL MILESTONES Global financial crisis - stock market crashed 2006 Pre-school added to school 2009 Fort Hood shooting - 12 servicemen killed, 31 injured An association formed with Grace Church in Hutchinson, thus Immanuel H1N1 (swine flu) global pandemic Lutheran School and Children of Grace Pre-School 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill - 4.9 million barrels of oil spilt into the Gulf of Mexico Pastors 2011 Gabrielle Giffords, U.S. Representative, shot & critically injured in Tucson, Ronald Siemers (1995-2001) Daniel Reich (2001-present) AZX, 6 others killed Principals/Teachers Osama bin Laden, U.S. most wanted terrorist, killed by U.S. Navy Seals in Timothy Schuh (1997-2006) Cheryl Schuh (1997-2006) Pakistan Koreen Koehler (2000-2002) Leanne Reich (2002-2004) A nuclear catastrophe in Tokyo resulted from a 9.0 earthquake in Japan Justin Groth (2006-2010) Heidi Groth (2006-2010) One of the deadliest tornado season known in U.S. history - amongst the most Kristin (Slovik) Utsch (2008-present) Alex Vandenberg (2010-present) devastating was in Joplin, MO Stephanie Vandenberg (2010-present) 2012 Hurricane Sandy caused devastation along the east coast - 132 deaths; $82 billion in damages WELS/LUTHERAN KEYPOINTS Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, CT - killed 26 people 2001 Time of Grace began airing on TV of which 20 were children between the ages of 6 and 7 2008 Christian Worship Supplement published 2013 Boston Marathon Bombings - two pressure cookers used in explosions; killed U.S. -

1 TABLE FEEDBACK from CAPP Town Hall

1 TABLE FEEDBACK FROM CAPP Town Hall Meeting VII – 04/08/04 Recommended name of plan: • UC: Creating a Universal Community • UC: Leading in the 21st Century • UC: A leader in the Urban Renaissance • UC 21: Leading Now and in the Future • UC: Urban Renaissance Plan • UC: Urban Integration Plan • UC: Reality Integration Plan • UC21: Vision, Action, Success • UC21: The Urban University without Boundaries • UC21: The Power of the Vision • UC 21: Leading the Urban Renaissance • Cincinnati Plan • “Leading” resonates • UC: Leading the Urban Renaissance • Negative connotations for “21” • Positive connotations for leadership, pioneer, and renaissance • U2C1: • UC: City Plan- city is more positive than urban • The Cincinnati Model • UC Urban Renaissance Plan • UC Urban Integration Plan • UC Reality Integration Plan • UC City Limits Plan • UC the future • Like UC 21 • Circles vs. triangles • Don’t like UC 21 or UC21 • Pioneer or renaissance sounds old • Urban- overused and negative • It’s all UC in the 21st century • Leading our Community • The Cincinnati Deal • Be inspiring, uplifting, positive, and powerful • UC: The Urban University for the 21st Century • UC: The Urban University for the 3rd Millennium • UC: 3rd Millennium Plan- 3rd millennium plan will take us seamlessly to 2999 • UC21: Leading Our Community Now and in the Future • UC 21st: Leading Our Community Now and in the Future • UC21: Unlimited Change • UC21: Uniquely Changing • UC21: University and Community 2 • UC21: University/Community • UC21: Upper Class! • UC21: Unique Community -

Scaling the State: Egypt in the Third Millennium BC

Originalveröffentlichung in: Archaeology International 17, 2014, S. 79-93 Bussmann, R 2014 Scaling the State: Egypt in the Third Millennium BC. Archaeology International, No. 17:pp, 79-93, DOI: http://dx.cloi.org/10.5334/ai.1708 RESEARCH ARTICLE Scaling the State: Egypt in the Third Millennium BC Richard Bussmann* Discussions of the early Egyptian state suffer from a weak consideration of scale. Egyptian archaeologists derive their arguments primarily from evidence of court cemeteries, elite tombs, and monuments of royal display. The material informs the analysis of kingship, early writing, and administration but it remains obscure how the core of the early Pharaonic state was embedded in the territory it claimed to administer. This paper suggests that the relationship between centre and hinterland is key for scaling the Egyptian state of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2,700- 2,200 BC). Initially, central administration imagines Egypt using models at variance with provincial practice. The end of the Old Kingdom demarcates not the collapse, but the beginning of a large-scale state characterized by the coalescence of central and local models. Imagining the state and early 20th century sociology. They gained In his book Seeing like a state, James Scott a stronger empirical foundation when archae (1998) argued that pre-modern states did ologists started engaging with the debate in not penetrate society to the same degree as the 20,h century (Claessen and Sokolnik 1978; their 2O‘h century successors did. According Feinman and Marcus, 1998). A leading recent to Scott, only the latter were able to imple protagonist, Norman Yoffee (2001; 2005) ment ideologies in wider society, including replied to Scott that archaic states did develop high-modernist fascism and communism, strategies similar to those of modern states. -

Lopes and Gomes Text.Indd

Between the 3rd and 2nd Millennia BC: Exploring Cultural Diversity and Change in Late Prehistoric Communities edited by Susana Soares Lopes Sérgio Alexandre Gomes Archaeopress Archaeology Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-922-7 ISBN 978-1-78969-923-4 (e-Pdf) © the individual authors and Archaeopress 2021 This work is funded by national funds through the FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the scope of the project UIDB/00281/2020 (Centro de Estudos em Arqueologia, Artes e Ciências do Património – Universidade de Coimbra). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents Chapter 1 Introduction: The Turning of Things .....................................................................................................................................1 Susana Soares Lopes and Sérgio Alexandre Gomes Chapter 2 The Northwest Iberian Peninsula Between the Late 3rd Millennium and Early 2nd Millennium BCE as a Mosaic of Cultural Identities ..............................................................................................................................................12 Ana M.S. Bettencourt Chapter -

Media 501186 En.Pdf

1 BANEA 2017 Grand Challenges and Blue Skies in the Study of the Ancient Near East University of Glasgow 4-6 January 2017 LIST OF ABSTRACTS www.banea2017.org 2 Interdisciplinary Approaches to Water History in the Ancient Near East: Material Remains, Science and Text Lecture Theatre Session Organisers: Duncan Keenan-Jones (University of Glasgow, UK) and Jaafar Jotheri (Durham University, UK & Al-Qadisiyah University, Iraq) Session Abstract: This one-day workshop will enable cross-fertilization between cutting-edge approaches to reconstructing the critical issue of water management across the broad chronological and geographical sweep of the Ancient Near East. Speakers are drawn from across the UK, Europe and Middle East. 1. Water management system in Third Millennium Southern Mesopotamian Towns Eloisa Casadei (Sapienza University of Rome) Understanding the relationship between water and ancient society still stimulates a vivid discussion both in historical and anthropological debate. Problems such as the control of riverine water through irrigation systems and the management of water in the urban compound have been seen by researchers as key to the rise of complexity during the 4th-3rd millennium BC. However, the archaeological data relating to the organization of water in the settlements are not always sufficient to explain the whole management system. In particular, 4th and 3rd millennium BC temples and palaces show a complex organization of shafts, basins and drains for which a functional reconstruction is still a matter of debate. While the so-called palaces included a sort of household organization similar to the private compound, water-related features inside the temples could play a more symbolic role.