Scaling the State: Egypt in the Third Millennium BC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3Rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria

The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Colantoni, C., and J. A. Ur. 2011. The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria. Iraq 73:21-69 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:5342153 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA VOLUME LXXIII • 2011 CONTENTS Editorial iii Obituaries: Dr Donny George Youkhanna, Mrs Rachel Maxwell-Hyslop v Jason Ur, Philip Karsgaard and Joan Oates: The spatial dimensions of early Mesopotamian urbanism: The Tell Brak suburban survey, 2003–2006 1 Carlo Colantoni and Jason Ur: The architecture and pottery of a late third-millennium residential quarter at Tell Hamoukar, north-eastern Syria 21 David Kertai: Kalæu’s palaces of war and peace: Palace architecture at Nimrud in the ninth century bc 71 Joshua Jeffers: Fifth-campaign reliefs in Sennacherib’s “Palace Without Rival” at Nineveh 87 M. P. Streck and N. Wasserman: Dialogues and riddles: Three Old Babylonian wisdom texts 117 Grégory Chambon and Eleanor Robson: Untouchable or unrepeatable? The upper end of the Old Babylonian metrological systems for capacity -

The Transforma Ion of Neolithic Socie

The Transformation of Neolithic Societies An Eastern Danish Perspective on the 3rd Millennium BC Iversen, Rune Publication date: 2015 Document version Other version Citation for published version (APA): Iversen, R. (2015). The Transformation of Neolithic Societies: An Eastern Danish Perspective on the 3rd Millennium BC. Jysk Arkaeologisk Selskab. Jysk Arkæologisk Selskabs Skrifter Vol. 88 Download date: 27. sep.. 2021 The Transformaion of Neolithic Socieies An Eastern Danish Perspecive on the 3rd Millennium BC Rune Iversen The Transformaion of Neolithic Socieies 1 The Transformaion of Neolithic Socieies An Eastern Danish Perspecive on the 3rd Millennium BC Rune Iversen Jutland Archaeological Society 3 The Transformaion of Neolithic Socieies An Eastern Danish Perspecive on the 3rd Millennium BC Rune Iversen © The author and Jutland Archaeological Society 2015 ISBN 978-87-88415-99-5 ISSN 0107-2854 Jutland Archaeological Society Publicaions vol. 88 Layout and cover: Louise Hilmar English revision: Anne Bloch and David Earle Robinson Printed by Narayana Press Paper: BVS mat, 130 g Published by: Jutland Archaeological Society Moesgaard DK-8270 Højbjerg Distributed by: Aarhus University Press Langelandsgade 177 DK-8200 Aarhus N Published with inancial support from: Dronning Margrethe II’s Arkæologiske Fond Farumgaard-Fonden and Lillian og Dan Finks Fond Cover: The Stuehøj (Harpagers Høj) passage grave, Ølstykke, Zealand Photo by: Jesper Donnis 4 Contents Preface ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

3Rd Millennium Sales

Taking Sales to a Higher Level 3rd Millennium Sales Mercuri International’s 3rd Millennium Sales Concept will help you pick and practice the skills required to transform yourself into a future proof sales professional. Why the Need to Adapt? Quite simply because the digital world has drastically increased the information available to your customers. In turn, customers progress through significantly more of their ’buying journey’ before even meeting a sales person. This ’Digital Maturity’ also becomes more prevelant across various industries: Digital Maturity* Across Various Industries IT TOURISM RETAIL BANKING DISTRIBUTION FAST MOVING CONSUMER GOODS INDUSTRY AND SERVICES HEALTHCARE PUBLIC SECTOR RETAIL HANDICRAFT AGRICULTURE BUILDING *Adapted from the article ‘Digital Advantage’ by Capgemini Consulting & MIT Sloan Management. Average Percentage of Buying Journey before engaging with a Sales Person Future proofing the Consider these statements: Sales Professional The sales profession has evolved with the times to meet the 57% of the customer buying journey is changing needs of every passing generation. It is now time, for completed digitally before the first serious another wave of change. The difference - this is not a gradual engagement with a sales person, said evolution. This is transformation. Even as technology transforms CEB & Google in their 2011 study - Digital the way Customers buy, it also calls for sellers to transform the Evolution in B2B Marketing. (Since revised way they sell. Those who heed this call and are willing to trans- to 67% in 2014). form, will ride this wave, taking their careers and organizations to greater heights. As Alvin Tofler predicted many years ago “The Research shows that the 80% of the illiterate of the 21st century will not be those who cannot read sales community using social media is and write, but those who cannot learn, unlearn, and relearn”. -

BIENNIAL REVIEW Drug-Free Schools and Campuses Calendar Year 2018 – Calendar Year 2019 University of Nebraska at Kearney 2504 9Th Ave, Kearney, NE 68849

BIENNIAL REVIEW Drug-Free Schools and Campuses Calendar Year 2018 – Calendar Year 2019 University of Nebraska at Kearney 2504 9th Ave, Kearney, NE 68849 Prepared by Biennial Review Committee George Holman, Associate Dean for Student Affairs Wendy Schardt, Director of Student Health & Counseling Dave Roberts, Assistant Dean for Student Affairs Kiphany Hof, Associate Director of UNK Counseling Amanda Dabney, Wellness Promotions and Prevention Coordinator Dawn Adams, Lieutenant, UNK Police Michelle Holman, Clery Coordinator, UNK Police August 2020 Report Overview I. University of Nebraska at Kearney Wellness Programming – Mission Statement Pg. 2 II. Alcohol & Other Drug Policy (AOD) Pg. 2 - AOD Policy Application & Enforcement - University Sanctions and Student Success Center Program Requirements - Policy Distribution Procedures - Student Violations of AOD Policy During Reporting Period - Considerations Regarding Policy & Student Violations III. Student Success Center – Counseling Services Pg. 5 IV. Programming During Reporting Period - Student Success Center - Programming - Professional Development V. Health Education Office Programming Strengths & Challenges Pg. 5 - Program Strengths - Program Challenges VI. Recommendations for Revision & Improvement Pg. 8 VII. Appendix Pg. 8 1 I. University of Nebraska Kearney Wellness Programming – Mission Statement The Health Education Office works to Engage, Educate, and Empower students on how to make wise choices when it comes to alcohol & tobacco use, mental health wellbeing, and healthy living. Their mission is to alleviate persistence problems caused by alcohol abuse by better educating the University of Nebraska at Kearney (UNK) students on the dangers of high-risk drinking, creating positive changes in students’ attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors regarding alcohol use. The office works to ensure that prevention messages, enforcement efforts, educational materials, alternative resources, assessments, and analysis, are all universally streamlined. -

11. Cultural Contacts and Mobility Between the South Central Mediterranean and the Aegean During the Second Half of the 3Rd Millennium BC

CULTURAL CONTACTS AND MOBILITY 243 11. Cultural contacts and mobility between the south central Mediterranean and the Aegean during the second half of the 3rd millennium BC ALBERTO CAZZELLA, ANTHONY PACE AND GIULIA RECCHIA Abstract One of the effects of the reconfiguration of world prehistoric chronolo- gies as a result of radiocarbon dating has been the questioning of hith- erto established frameworks of connectivity and the movement of peo- ple, materials and ideas in prehistory. This contribution revisits issues of connectivity between the south-central Mediterranean region and the Aegean during the Early Bronze Age. This short study highlights the need for scholars to re-examine connectivity using, as an example, diagnostic archaeological evidence of intra-regional links between South Italy, Sic- ily and Malta and the Aegean, that was not affected by carbon dating. The paper suggests that while broader regional patterns of connectivity may have benefited from revised chronologies of world prehistory, mi- cro-regional cultural links may require new explanations of crossings and the evident movement of commodities by land and by sea. Radiocarbon dating and the re-examination of diffusionist thinking during the post World War II decades raised several questions concern- ing the nature of cultural contact across the Mediterranean during late prehistory. Seminal work by Colin Renfrew (1973) on the effects of new chronologies, served to emphasise the discordant cultural links that older dating frameworks had suggested. Hitherto established theories of hu- man mobility involving extensive geographic areas, as well as links be- tween small communities of the Mediterranean, also came under close 244 ALBERTO CAZZELLA, ANTHONY PACE AND GIULIA RECCHIA scrutiny and, in many cases, were abandoned altogether. -

The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3Rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria

The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Colantoni, C., and J. A. Ur. 2011. The Architecture and Pottery of a Late 3rd Millennium BC Residential Quarter at Tell Hamoukar, Northeastern Syria. Iraq 73:21-69 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:5342153 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA VOLUME LXXIII • 2011 CONTENTS Editorial iii Obituaries: Dr Donny George Youkhanna, Mrs Rachel Maxwell-Hyslop v Jason Ur, Philip Karsgaard and Joan Oates: The spatial dimensions of early Mesopotamian urbanism: The Tell Brak suburban survey, 2003–2006 1 Carlo Colantoni and Jason Ur: The architecture and pottery of a late third-millennium residential quarter at Tell Hamoukar, north-eastern Syria 21 David Kertai: Kalæu’s palaces of war and peace: Palace architecture at Nimrud in the ninth century bc 71 Joshua Jeffers: Fifth-campaign reliefs in Sennacherib’s “Palace Without Rival” at Nineveh 87 M. P. Streck and N. Wasserman: Dialogues and riddles: Three Old Babylonian wisdom texts 117 Grégory Chambon and Eleanor Robson: Untouchable or unrepeatable? The upper end of the Old Babylonian metrological systems for capacity -

Analyzing the Case of Kenya Airways by Anette Mogaka

GLOBALIZATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY: ANALYZING THE CASE OF KENYA AIRWAYS BY ANETTE MOGAKA UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY - AFRICA SPRING 2018 GLOBALIZATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY: ANALYZING THE CASE OF KENYA AIRWAYS BY ANETTE MOGAKA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL STUDIES (SHSS) IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS DEGREE IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY - AFRICA SUMMER 2018 STUDENT DECLARATION I declare that this is my original work and has not been presented to any other college, university or other institution of higher learning other than United States International University Africa Signature: ……………………… Date: ………………………… Anette Mogaka (651006) This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as the appointed supervisor Signature: …………………. Date: ……………………… Maurice Mashiwa Signature: …………………. Date: ……………………… Prof. Angelina Kioko Dean, School of Humanities and Social Sciences Signature: …………………. Date: ……………………… Amb. Prof. Ruthie C. Rono, HSC Deputy Vice Chancellor Academic and Student Affairs. ii COPYRIGHT This thesis is protected by copyright. Reproduction, reprinting or photocopying in physical or electronic form are prohibited without permission from the author © Anette Mogaka, 2018 iii ABSTRACT The main objective of this study was to examine how globalization had affected the development of the airline industry by using Kenya Airways as a case study. The specific objectives included the following: To examine the positive impact of globalization on the development of Kenya Airways; To examine the negative impact of globalization on the development of Kenya Airways; To examine the effect of globalization on Kenya Airways market expansion strategies. -

Download Paper

Bell Beaker resilience? The 4.2ka BP event and its implications for environments and societies in Northwest Europe Jos Kleijne, Mara Weinelt, Johannes Müller Abstract This paper deals with the Bell Beaker phenomenon in Northwest Europe, and the question of its development around 2200 BC, in relation to the well-known 4.2ka climatic event. The duration of settlement occupation and the subsistence economy are the variables used in this study to address this resilience on a regional scale. Concluding, we state that regional variability exists in the ways in which communities were impacted by the 4.2ka event. In addition to agricultural intensification, the flexibility of subsistence strategies seems to have played an important role. Keywords Resilience; Bell Beaker; Northwest Europe; Settlement; Subsistence Introduction From 2600 BC onwards, Western and Central Europe are characterised by what archaeologists have historically labelled as “the Bell Beaker phenomenon” (e.g. Vander Linden 2013). In various parts of Europe, especially the Iberian Peninsula, the end of this phenomenon is often considered to date around 2200 BC, with the rise of the El Argar civilisation in the Southeast of the Peninsula, associated with significant changes in social organisation, settlement structure and food economy (Lull et al 2015). The role of climate in the demise of the Bell Beaker phenomenon, and the resilience and vulnerability of prehistoric communities, is currently being debated (e.g. Blanco-Gonzalez et al 2018; Hinz et al in press). Specifically, an abrupt climatic event around 2200 BC, commonly known as ‘the 4.2ka event’, has a well attested influence on human society in other parts of the world. -

Sumerian Arsenic Copper and Tin Bronze Metallurgy (5300-1500 BC): the Archaeological and Cuneiform Textual Evidence

Archaeological Discovery, 2021, 9, 185-197 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ad ISSN Online: 2331-1967 ISSN Print: 2331-1959 Sumerian Arsenic Copper and Tin Bronze Metallurgy (5300-1500 BC): The Archaeological and Cuneiform Textual Evidence Lucas Braddock Chen Foundation for the Advancement of Anthropology & History, Menlo Park, USA How to cite this paper: Chen, L. B. (2021). Abstract Sumerian Arsenic Copper and Tin Bronze Metallurgy (5300-1500 BC): The Archaeo- Copper was one of the first metals to be utilized since 8000 BC. Arsenic cop- logical and Cuneiform Textual Evidence. per became popular due to its lower melting point and decreased metal po- Archaeological Discovery, 9, 185-197. rosity, allowing for the creation of longer metal blades. Tin bronze began ap- https://doi.org/10.4236/ad.2021.93010 pearing around 3500 BC, and its superior recyclability and malleability made Received: June 19, 2021 it the favorite metal alloy until the prevalence of iron. Bronze alloy was li- Accepted: July 9, 2021 mited by its requirement of tin, which was more difficult to acquire than Published: July 12, 2021 copper in ancient Mesopotamia. This manuscript describes the ancient trade Copyright © 2021 by author(s) and of copper and tin based on the cuneiform texts. The paper will also list the Scientific Research Publishing Inc. cuneiform texts that described steps of metallurgy, including the tools, fur- This work is licensed under the Creative naces, and crucibles utilized in Sumerian metallurgy. This paper reports the Commons Attribution International analysis of the metallurgy techniques described by cuneiform to the chemical License (CC BY 4.0). -

Elam and Babylonia: the Evidence of the Calendars*

BASELLO E LAM AND BABYLONIA : THE EVIDENCE OF THE CALENDARS GIAN PIETRO BASELLO Napoli Elam and Babylonia: the Evidence of the Calendars * Pochi sanno estimare al giusto l’immenso benefizio, che ogni momento godiamo, dell’aria respirabile, e dell’acqua, non meno necessaria alla vita; così pure pochi si fanno un’idea adeguata delle agevolezze e dei vantaggi che all’odierno vivere procura il computo uniforme e la divisione regolare dei tempi. Giovanni V. Schiaparelli, 1892 1 Babylonians and Elamites in Venice very historical research starts from Dome 2 just above your head. Would you a certain point in the present in be surprised at the sight of two polished Eorder to reach a far-away past. But figures representing the residents of a journey has some intermediate stages. Mesopotamia among other ancient peo- In order to go eastward, which place is ples? better to start than Venice, the ancient In order to understand this symbolic Seafaring Republic? If you went to Ven- representation, we must go back to the ice, you would surely take a look at San end of the 1st century AD, perhaps in Marco. After entering the church, you Rome, when the evangelist described this would probably raise your eyes, struck by scene in the Acts of the Apostles and the golden light floating all around: you compiled a list of the attending peoples. 3 would see the Holy Spirit descending If you had an edition of Paulus Alexan- upon peoples through the preaching drinus’ Sã ! Ğ'ã'Ğ'·R ğ apostles. You would be looking at the (an “Introduction to Astrology” dated at 12th century mosaic of the Pentecost 378 AD) 4 within your reach, you should * I would like to thank Prof. -

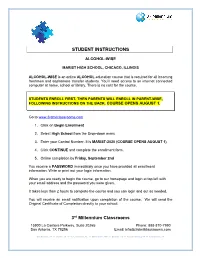

STUDENT INSTRUCTIONS 3Rd Millennium Classrooms

STUDENT INSTRUCTIONS ALCOHOL-WISE MARIST HIGH SCHOOL, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS ALCOHOL-WISE is an online ALCOHOL education course that is required for all incoming freshmen and sophomore transfer students. You’ll need access to an internet connected computer at home, school or library. There is no cost for the course. STUDENTS ENROLL FIRST. THEN PARENTS WILL ENROLL IN PARENT-WISE, FOLLOWING INSTRUCTIONS ON THE BACK. COURSE OPENS AUGUST 1. Go to www.3rdmilclassrooms.com 1. Click on Begin Enrollment 2. Select High School from the Drop-down menu 3. Enter your Control Number. It is MARIST-2020 (COURSE OPENS AUGUST 1) 4. Click CONTINUE and complete the enrollment form. 5. Online completion by Friday, September 2nd You receive a PASSWORD immediately once you have provided all enrollment information. Write or print out your login information. When you are ready to begin the course, go to our homepage and login at top left with your email address and the password you were given. It takes less than 2 hours to complete the course and you can login and out as needed. You will receive an email notification upon completion of the course. We will send the Original Certificate of Completion directly to your school. rd 3 Millennium Classrooms 15900 La Cantera Parkway, Suite 20265 Phone: 888-810-7990 San Antonio, TX 78256 Email: [email protected] San Antonio, TX <> Austin, TX <> Ft. Lauderdale, FL <> Minneapolis, MN <> Boulder, CO <> Fredericksburg, VA <> Sacramento, CA PARENT WISE INSTRUCTIONS MARIST HIGH SCHOOL, CHICAGO, ILLINOIS PARENT-WISE is a FREE online alcohol education course designed for Marist parents. -

Islamic Republic of Iran

Grids & Datums ISLAM I C REPUBL I C OF IR AN by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “Archaeologists suggest that during Neolithic times small numbers Reza Shah aimed to improve the status of women and to that end of hunters lived in caves in the Zagros and Alborz Mountains and in he made wearing the chador (black cloak) illegal. Like Atatürk, too, the southeast of the country. Iran’s first organized settlements were he insisted on the wearing of Western dress and moved to crush the established in Elam, the lowland region in what is now Khuzestan power of the religious establishment. However, Reza had little of the province, as far back as the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. Elam subtlety of Atatürk and his edicts made him many enemies. Some was close enough to Mesopotamia and the great Sumerian civilization women embraced his new dress regulations, but others found them to feel its influence, and records suggest the two were regular oppo- impossible to accept. nents on the battlefield. The Elamites established their capital at Shush “On his return to Iran on 1 February 1979, Khomeini told the exul- and derived their strength through a remarkably enlightened federal tant masses of his vision for a new Iran, free of foreign influence and system of government that allowed the various states to exchange true to Islam: ‘From now on it is I who will name the government’. the natural resources unique to each region. The Elamites’ system of Ayatollah Khomeini soon set about proving the adage that ‘after inheritance and power distribution was also quite sophisticated for the revolution comes the revolution’.