Evaluating the Well-Being, Impact and Legacy of Singing a Child's Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

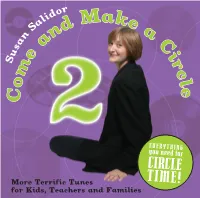

C Ome and Make a Circle

r do li ake a M a S d n n C a a i s r u e c S l m e o C EVERYTHING you need for CIRCLE TIME! More Terrific Tunes for Kids, Teachers and Families Come and Make a Circle 2 More Terrific Tunes for Kids, Teachers and Families In this follow up recording to the first Come and Make a Circle you will find more songs and fingerplays guaranteed to make your circle times fun and successful. Once again I invite you to use all or any part of this CD to create your own circle time repertoire. The songs are divided into the following categories: Let’s Sing, Favorite Fingerplays, Rhythm & Rhyme, Songs That Teach, Old Favorites, and Time to End. Each category contains a handful of songs that will engage and entertain children from 1–6 years. These songs have been carefully selected so that they can be easily learned by early childhood educators with or without prior musical experience. You will find the lyrics to the songs and fingerplays in this booklet, but for teaching tips and movement suggestions, please visit my website at www.susansalidor.com and look for the special Come and Make a Circle 2 button. For more songs and fingerplays for the classroom and home, try Come and Make a Circle, winner of the following awards: Parents’ Choice, NAPPA, iParenting Media, and the Oppenheim Toy Portfolio Gold Award. All of my recordings for children are available at my website (www.SusanSalidor.com) and through dozens of online distributors. -

Benger, Kurt Oral History Interview Steve Hochstadt Bates College

Bates College SCARAB Shanghai Jewish Oral History Collection Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library 6-8-1990 Benger, Kurt oral history interview Steve Hochstadt Bates College Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/shanghai_oh Recommended Citation Hochstadt, Steve, "Benger, Kurt oral history interview" (1990). Shanghai Jewish Oral History Collection. 1. http://scarab.bates.edu/shanghai_oh/1 This Oral History is brought to you for free and open access by the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Shanghai Jewish Oral History Collection by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interview with Kurt Benger by Steve Hochstadt Shanghai Jewish Community Oral History Project Summary Sheet and Transcript Interviewee Benger, Kurt Interviewer Hochstadt, Steve Transcriptionists Das, Kankana Vazirani, Jyotika Hochstadt, Steve Date 6/8/1990 Extent 2 audiocassettes Place Long Beach, California Use Restrictions © Steve Hochstadt. This transcript is provided for individual Research Purposes Only; for all other uses, including publication, reproduction and quotation beyond fair use, permission must be obtained in writing from: Steve Hochstadt, c/o The Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library, Bates College, 70 Campus Avenue, Lewiston, Maine 04240-6018. Biographical Note Kurt Benger was born in Grimmen, Germany, in November 1908. He worked in the clothing business, but was fired from Karstadt in Hamburg in April 1933 because he was Jewish. He later moved to Berlin, where he got married on November 15, 1938, just before they left for Shanghai on November 23. In Shanghai he held many jobs, and had to take care of his wife, Friedel, who was very sick. -

Stories from the Heart of Australia, the Stories of Its People

O UR GIFT TO Y O U Stories from the PENNING THE P ANDEMIC EDIT ED B Y J OHANNA S K I NNE R & JANE C O NNO L LY Inner Cover picture – Liz Crispie Inner Cover design – Danielle Long Foreword – Johanna Skinner and Jane Connolly Self-Isolation – Margaret Clifford Foreword Late in 2019 news reports of a highly virulent virus were emerging from China. No one could imagine then what would follow. As a general practitioner working at a busy Brisbane surgery, I really did not think that it would affect us that much. How wrong I was. Within months, the World Health Organisation had named the virus COVID 19 and a pandemic was declared. Life as we knew it was changed, perhaps forever. I was fortunate to be part of a practice that had put protocols in place should the worst happen, but even so, I felt overwhelmed by the impact on the patients that I was in contact with daily. They poured their hearts out with stories of resilience, heartache and lives changed irrevocably. I contacted my friend Jane, an experienced editor and writer, about my idea to collect these tales into an anthology. In less than five minutes, she responded enthusiastically and became its senior editor, bringing her years of experience and sharp eye to detail to the anthology. Together, we spent many weekends over pots of tea and Jane’s warm scones reading the overwhelming number of stories and poems that the public entrusted to us. Our greatest regret was that we couldn’t accommodate every piece we received. -

The ONE and ONLY Ivan

KATHERINE APPLEGATE The ONE AND ONLY Ivan illustrations by Patricia Castelao Dedication for Julia Epigraph It is never too late to be what you might have been. —George Eliot Glossary chest beat: repeated slapping of the chest with one or both hands in order to generate a loud sound (sometimes used by gorillas as a threat display to intimidate an opponent) domain: territory the Grunt: snorting, piglike noise made by gorilla parents to express annoyance me-ball: dried excrement thrown at observers 9,855 days (example): While gorillas in the wild typically gauge the passing of time based on seasons or food availability, Ivan has adopted a tally of days. (9,855 days is equal to twenty-seven years.) Not-Tag: stuffed toy gorilla silverback (also, less frequently, grayboss): an adult male over twelve years old with an area of silver hair on his back. The silverback is a figure of authority, responsible for protecting his family. slimy chimp (slang; offensive): a human (refers to sweat on hairless skin) vining: casual play (a reference to vine swinging) Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Glossary hello names patience how I look the exit 8 big top mall and video arcade the littlest big top on earth gone artists shapes in clouds imagination the loneliest gorilla in the world tv the nature show stella stella’s trunk a plan bob wild picasso three visitors my visitors return sorry julia drawing bob bob and julia mack not sleepy the beetle change guessing jambo lucky arrival stella helps old news tricks introductions stella and ruby home -

Date: December 5-6, 2020 Speaker: Paul Mcilwraith – Teaching Pastor Scripture: the Songs of Christmas

He was planning on moving out of downtown London to suburbia in a small town just outside the city. I was a little skeptical. Like I said, I am a similar age but I am a grandpa. Just thinking of the energy needed to raise children at my age, I get exhausted. Grandkids, you can get them all fired up, then give them back to their parents and go have a nap. Date: December 5-6, 2020 Speaker: Paul McIlwraith – Teaching Pastor Carolyn and I did the pre-marriage counselling with Scripture: The Songs of Christmas - Zechariah Rob and Amanda and saw just how much they loved each other and were together in this. I officiated at their wedding in 2019 and a short while I met Rob around five years ago. Pre-COVID days, later their son, Samuel was born. I can say that I he attends our Saturday night service. He began to have never seen Rob happier and more content. He write me notes just sharing some things he was is a wonderful father to little Sam. learning from the sermons and that led to us going out to dinner and getting to know each other a bit I took a moment to ask him about it. Have a look at better. Rob is a few years older than me but in much the video. better shape. Did you noticed for Rob, the only hesitancy in Through the course of the conversation, I found he having a child this late in his life was, societal was a big hockey fan and has a very successful norms. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Old Bush Songs Composed and Sung in the Bushranging, Digging and Overlanding Days

Old Bush Songs Composed and Sung in the Bushranging, Digging and Overlanding Days Edited by Paterson, Andrew Barton (1864-1941) A digital text sponsored by University of Sydney Library Sydney 1999 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ © 1999 University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission. Source Text: Prepared against the print edition published by Angus and Robertson, Sydney 1905 All quotation marks retained as data All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. First Published: 1905 821.08 Australian Etexts poetry verse 1890-1909 The Old Bush Songs Composed and Sung in the Bushranging, Digging and Overlanding Days Edited by A.B. Paterson Sydney Angus and Robertson 1905 Preface The object of the present publication is to gather together all the old bush songs that are worth remembering. Apart from other considerations, there are many Australians who will be reminded by these songs of the life of the shearing sheds, the roar of the diggings townships, and the campfires of the overlanders. The diggings are all deep sinking now, the shearing is done by contract, and the cattle are sent by rail to market, while newspapers travel all over Australia; so there will be no more bush ballads composed and sung, as these were composed and sung, as records of the early days of the nation. In their very roughness, in their absolute lack of any mention of home ties or of the domestic affections, they proclaim their genuineness. -

Cd Lyrics Double Yodel

Lyrics for the CD DOUBLE YODEL by Lou and Peter Berryman Recorded in 1995 All songs © L&P Berryman Words by Peter, Music by Lou 1 Pushing Spring 2 IF (Dueling Paranoias) 3 Gadeng Vadoo 4 Orange Cocoa Cake 5 Science Marches On 6 Pair of Geese 7 Double Yodel 8 Dog of Time 9 Mr. Frenkl 10 New Listing 11 We Strolled on the Beach 12 Come to Mind 13 Every Week Lou and Peter Berryman Box 3400 Madison WI 53704 LOUANDPETER.COM [email protected] [email protected] 1 PUSHING SPRING (aka PUSHING SPRING TANGO) ©1994 L&P Berryman INTRO: Timing is a factor, fellas, everywhere you go Don't fall for a skier on the first good day of snow Don't fall for a dancer when the Bolshoi is in town And don't fall for a gardner, Boys, as winter's winding down: It isn't forty four degrees There is no green yet in the trees It may be March but even so, there's still a foot of snow Tonight it's gonna freeze What green there is is in her thumb As her seed catalogs have come She can take those five below nights, as long as she has Gro-lights Her life is not so glum CHORUS: Don't try to tell her she hasta wait for robins to sing Don't ever say she's jumping the gun by pushing the spring She'll wave a dirty trowel and say so what if i do If you had spent your life in Wisconsin, you'd push it too You could try wooing her with wine Although you'll have to stand in line Behind a tuber in a tub; an ornamental shrub And cuttings off a vine Don't bring her poems of romance But know the names of all her plants Don't buy a diamond to surprise her, but bring some fertilizer -

Steele, Shirley

City of Alexandria Office of Historic Alexandria Alexandria Legacies Oral History Program Project Name: Alexandria Legacies Title: Interview with Shirley Ann Steele Date of Interview: August 13, 2008 Location of Interview: Alexandria, Virginia Interviewer: Logan Wiley Transcriber: Jo-Ann LaFon and Robert Colton Abstract: Shirley Sanderson Steele was born and raised in Alexandria. She recalls her childhood home, neighborhood and many African American owned businesses. While raising her family she completed and received her high school diploma. She and her second husband, Mr. Steele, also spend time talking about segregation in Alexandria, the struggle for civil rights including library sit-ins and the benefits of integration. Interview with Shirley Steele, August 13, 2008 Page 2 of 13 Table of Contents/Index Tape: Tape 1 Side: Side 1 Minute Counter Page Topic Not 001 3 Medical Care for African Americans During Segregation indicated 3 Childhood Home 4 Early Schooling 5 Neighborhood 5 Segregation and Integration in Alexandria 6 Black Businesses, Social Organizations and Churches 9 Returning to School Tape: Tape 1 Side: Side 2 Minute Counte Page Topic r Not 10 Family indicated 11 Segregation and Civil Rights in Alexandria Interview with Shirley Steele, August 13, 2008 Page 3 of 13 Medical Care for African Americans During Segregation Logan Wiley: Were you born in Alexandria and if so, were you born at a hospital or at home? Shirley Steele: I was born in Alexandria and, I believe, I was born in Alexandria Hospital. At that time, it was located on Duke Street. L.W.: And what was the medical care like for black people at that time? Shirley Steele: As far back as I can remember, we had to go to a clinic and the clinic was located on Columbus Street—the side entrance of the hospital. -

Lemonade and Black Women As Audiences and Subjects

. Volume 14, Issue 2 November 2017 ‘She made angry Black woman something that people would want to be’: Lemonade and Black women as audiences and subjects Ashton Toone, Amanda Nell Edgar & Kelly Ford, University of Memphis, USA. Abstract: Based on interviews with 35 audience members, this essay argues that audiences used Beyoncé’s hour-long visual album, Lemonade, as a Two-Way Mirror to understand racial and gendered identities through the lenses of social movements, identity politics, and relationality. Our findings support Sandvoss (2005) and other audience scholars in that the Black women we interviewed used the album’s emphasis on Black femininity as a ‘mirror’ that uplifted their own racial and gendered identities. White and male audiences, on the other hand, used the album less for fashioning their own sense of self, instead using Lemonade as a lens to gaze into a realm of Black femininity as presented by Beyoncé, a Black woman herself. While in some cases, this perspective drove White and male participants’ empathy and support of the Black women’s experiences represented in the album, their understandings also risked one-dimensionality. Keywords: Audience Studies; Beyoncé; Black Identity; Intersectionality; Popular Music I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me. (Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man) The most disrespected person in America is the Black woman. The most unprotected person in America is the Black woman. The most neglected person in America is the Black woman. (Malcolm X, Los Angeles, May 1962) For the last few years, Beyoncé has sparked conversation both in the media and in scholarly literature for her recent singles like ‘Formation’, her 2016 Super Bowl performance that Page 203 Volume 14, Issue 2 November 2017 nodded to the Black Panther Party, and most recently her visual album Lemonade that celebrates Black culture and depicts the realities of social justice issues. -

Chapter 1: Parts of Speech Overview, Pp. 1–25

L09NAGUMA10_001-012.qxd 12/11/07 2:28 PM Page 1 Chapter 1: Parts of Speech 14. Leslie always lapses into baby talk when Overview, pp. 1–25 she sees a litter of kittens. Common, Proper, Concrete, and Abstract Nouns, 15. The band included one song that sounded as p. 1 if it had been recorded in an echo chamber. EXERCISE Com, A [or Con] 16. The class presented Ms. Stockdale with a 1. A constitution may have a bill of rights. bouquet of baby’s breath. 2. The Constitution of the United States guar- Com, A 17. The TV weatherperson explained to the antees freedomof speech. P, Con audience how a barometer works. 3. The Works Progress Administration existed 18. In order to get a good batch of cookies, you during the Great Depression. need to use the best oatmeal available. 4. That candidate is a staunch supporter of a Com, A [or Con] 19. A school of killer whales followed in the republican form of government. P, Con wake of the ship. 5. The Articles of Confederation were y of the instructor. 20. The bird-watchers were awe-struck as the approved in 1781. flock of geese lifted into the sky. 6. This document established “a firm league Com, A of friendship” among the states. Pronouns and Antecedents, p. 3 Com, Con Possessive pronouns in items 1 and 3, Ex. A, and 7. The editorial in today’s newspaper items 14 and 15, Ex. B, also may be identified as defended the proposed amendment. possessive adjectives. P, Con 8. -

August 17, 2016 Bulletin

ROTARY NOTES A publication of the Rotary Club of Warren, Ohio Rotary Upcoming Club of Warren Speakers August 3 August 17, 2016 Venita Collins – Foster Parenting Member Assignments August 10 Greeters Legendary Football Great Please Arrive by 11:50 a.m. Paul Warfield 8/24 – Chris Shape 8/31 – Judy Masaki - 9/7 – Bill Beinecke August 17 Zachary Svette – Mobile Meals Trumbull Metro 8/26 – Pat Miller and Jerry Donohoe Parks 9/2 – Dan Rowland and Cleo Royster 9/9 – Genevieve Bauman and Dan DelliQuadri August 24 Paulette Fellowship Eddington – August – Chris Shape Trumbull September - TBA Family Fitness Invocation 8/24 – Dave Jenkins August 31 8/31 – Andy Bednar Dick 9/7 – Denise May Thompson - Peter Allen Inn & Convention Center Rotary Serving Humanity Weekly News and Announcements Rotary Motto Hello Rotarians and Friends! I hope all of you are doing well on this perfect summer day! This is MY kind of weather. I finally had a chance to Service Above give the AC a break and open windows and let the breeze blow through the Self house. Last night, I could actually fall asleep to the sounds of crickets chirping. Fabulous! 4-Way Attendance was down a bit at this week’s meeting, but it didn’t stop us from Test having a great time. Chris Shape was back on Fellowship and I can’t believe he hasn’t yet told a Browns/Steelers joke! Maybe it’s because there is so Of the things much political fodder to choose from. Oh, well. It will be interesting to see we think, say what he comes up with this Wednesday.