Motion in Limine to Exclude Certain Evidence and Arguments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 2:11-Cr-00045-MRH Document 1005 Filed 09/07/12 Page 1 of 12

Case 2:11-cr-00045-MRH Document 1005 Filed 09/07/12 Page 1 of 12 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, Criminal No. 11-0045 ELECTRONICALLY FILED v. JEREMIAH MANGHAN, ANDRE ALLEN, KEENAN BLACK, RANDALE CHAPMAN, LAMONT HUNTER, DERON NIXON. Defendant. MEMORANDUM ORDER RE: DEFENDANTS’ PRE-TRIAL MOTIONS On February 15, 2011, an indictment was filed against twenty Defendants charging them with various offenses including conspiracy to distribute and possession with intent to distribute heroin and firearm offenses. Doc. No. 1. On June 7, 2011, a superseding indictment was filed charging twenty-four Defendants with similar offenses. Doc. No. 273. Since that time, eighteen of the twenty-four Defendants have changed their plea and pled guilty to the offenses(s) charged or, pursuant to a plea agreement, a lesser included offense.1 Many of these Defendants have already been sentenced by this Court. The only Defendants who have not pled guilty are: Jeremiah Manghan (1), Andre Allen (2), Keenan Black (4), Randale Chapman (7), Lamont Hunter (12), and Deron Nixon (17). On July 31, 2012, the Court entered a Pre-Trial Order setting deadlines for pre-trial matters and setting trial for October 29, 2012. Doc. No. 965. 1 Defendant Eric Durah had the charges against him in 11-cr-0045 dismissed due to his change of plea to guilty in 11-cr-310. Case 2:11-cr-00045-MRH Document 1005 Filed 09/07/12 Page 2 of 12 Defendants who are proceeding to trial have filed seventeen pre-trial motions at various dates. -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Iowa Cedar Rapids Division

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF IOWA CEDAR RAPIDS DIVISION CRST EXPEDITED, INC, Plaintiff, No. 17-CV-25-CJW-KEM vs. MEMORANDUM OPINION SWIFT TRANSPORTATION CO OF AND ORDER IN LIMINE ARIZONA, LLC, Defendant. ____________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. PLAINTIFF’S MOTION IN LIMINE................................................... 4 A. Defendant’s Affirmative Defenses ............................................... 4 1. Invalidity Defenses ......................................................... 4 2. Voidability Defenses ....................................................... 5 3. Blacklisting Statutes and Antitrust Defenses ........................... 6 B. Other Lawsuits ...................................................................... 7 C. Plaintiff Has Not Sued the Drivers at Issue for Breach of Contract ........ 9 D. Advice of Counsel .................................................................10 E. Settlement Discussions ............................................................12 F. Related Corporations ..............................................................13 Case 1:17-cv-00025-CJW-KEM Document 214 Filed 07/08/19 Page 1 of 35 G. Witnesses Not Called to Testify .................................................13 H. Hearsay of Declarants Not Appearing to Testify at Trial ...................14 I. Items Not Subject of Discovery .................................................17 J. Expert Witnesses Not Disclosed in Discovery ................................18 K. Exhibits and Witnesses -

Case 6:16-Cv-01055-JTM Document Filed 01/11/18 Page 1 of 9

Case 6:16-cv-01055-JTM Document Filed 01/11/18 Page 1 of 9 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS HIBU, INC., Plaintiff, v. Case No. 16-1055-JTM CHAD PECK, Defendant. MEMORANDUM AND ORDER ON MOTIONS IN LIMINE This matter is before the court on the parties’ motions in limine filed in anticipation of the upcoming trial. Defendant filed a motion in limine as to experts (Dkt. 312) and another motion in limine on liability (Dkt. 313). Plaintiff filed seven separate motions in limine concerning its corporate history, employment agreements defendant claims he signed, hearsay statements, and other matters that are inadmissible under the federal rules of evidence (Dkts. 314–20). For the reasons stated below, defendant’s motion regarding plaintiff’s experts is denied. Defendant’s motion regarding liability is granted in part and taken under advisement until trial. Plaintiff’s motions are granted in part, denied in part without prejudice, and taken under advisement until trial. I. Legal Standards “The purpose of an in limine motion is to aid the trial process by enabling the Court to rule in advance of trial on the relevance of certain forecasted evidence, as to Case 6:16-cv-01055-JTM Document Filed 01/11/18 Page 2 of 9 issues that are definitely set for trial, without lengthy argument at, or interruption of, the trial.” Altman v. New Rochelle Pub. Sch. Dist., No. 13 CIV. 3253 (NSR), 2017 WL 66326, at *5 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 6, 2017) (quoting Palmieri v. Defaria, 88 F.3d 136, 141 (2d Cir. -

P:\04Cv471 Order Re Motions in Limine.Wpd

Case 2:04-cv-00471 Document 169 Filed in TXSD on 01/16/08 Page 1 of 14 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS CORPUS CHRISTI DIVISION TAURUS BROWN, § § v. § C.A. NO. C-04-471 § CHRISTOPHER CARR, ET AL. § ORDER REGARDING PLAINTIFF’S MOTIONS IN LIMINE This is a civil rights action filed by a prisoner pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Pending are plaintiff’s motions in limine and first amended motions in limine. (D.E. 145, 153). Specifically, plaintiff seeks a ruling on twenty-six matters in advance of trial. Defendant has not filed a response to this motion.1 For the reasons given below, the motion is GRANTED in part and DENIED in part. I. LEGAL STANDARDS FOR MOTIONS IN LIMINE. The Fifth Circuit has observed that “[m]otions in limine are frequently made in the abstract and in anticipation of some hypothetical circumstance that may not develop at trial.” Collins v. Wayne Corp., 621 F.2d 777, 784 (5th Cir. 1980). The Collins court further explained that When a party files numerous motions in limine, the trial court may not pay close attention to each one, believing that many of them are purely hypothetical. Thus, a party whose motion in limine has been overruled must object when the error he sought to prevent with his motion in limine is about to occur at trial. This will give the trial court an opportunity to reconsider the grounds of the motion in light of the actual instead of hypothetical circumstances at trial. -

Circuit Court Clerks' Manual

CIRCUIT COURT CLERKS’ MANUAL - CIVIL Pre-Trial PAGE 4-1 Chapter 4 - Pre-Trial Pretrial Conferences Rule 4:13, titled Pretrial Procedures; Formulating Issues reads as follows: The court may in its discretion direct the attorney for the parties to appear before it for a conference to consider: ● A determination of the issues; ● A plan and schedule of discovery; ● Any limitations on the scope and methods of discovery; ● The necessity or desirability of amendments to the pleadings; ● The possibility of obtaining admissions of fact and of documents which will avoid unnecessary proof; ● The limitation of the number of expert witnesses; ● The advisability of a preliminary reference of issues to a master for findings to be used as evidence when the trial is to be by jury; ● Such other matters as may aid in the disposition of the action. The court shall make an order which recites the action taken at the conference, the amendments allowed to the pleadings, the agreements made by the parties as to any of the matters considered, and which limits the issues for trial to those not disposed of by admissions or agreements of counsel; and such order when entered controls the subsequent course of the action, unless modified at the trial to prevent manifest injustice. This rule is designed to allow the court to consider such matters as will aid it in the disposition of the case in subsequent proceedings. It is not intended to substitute a new way of trying a case when an issue of fact exists. In most cases, judges will require counsel to meet with the judge in chambers prior to the trial to dispose of preliminary matters. -

02-20332-Ml/V ) MELTON DEAN HENNINGS, ) ) Defendant

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE WESTERN DIVISION _________________________________________________________________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) vs. ) No. 02-20332-Ml/V ) MELTON DEAN HENNINGS, ) ) Defendant. ) _________________________________________________________________ REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION ON DEFENDANT’S PRETRIAL MOTIONS _________________________________________________________________ Before the court are the following motions filed by the defendant, Melton Dean Hennings, on December 17, 2002: 1. Motion to Require the Government to Produce Jencks, Brady, and Giglio Material and to Comply with Rule 26.2 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure; 2. Motion for Disclosure of Promises, Etc. to Government Witnesses; 3. Motion for the Government to Give Notice of its Intention to use Evidence of Other Crimes, Wrongs, or Bad Acts under Fed. R. Evid. 404(b); 4. Motion for Disclosure of Expert Witness Testimony Pursuant to Fed. Crim. Rule 16(a)(1)(E); 5. Motion to Reveal Identity of Informants; 6. Motion in Limine (a motion to exclude “tip” testimony); 7. Motion for Bill of Particulars; and 8. Motion to Allow Time for Filing of Any Additional Motions. All the motions were referred to the United States Magistrate Judge for reports and recommendations. The government filed a consolidated response on December 23, 2002. For the following reasons, it is recommended that all motions be denied. BACKGROUND On September 12, 2002, the grand jury returned a fifteen count indictment against the defendant, Melton Hennings. The indictment included ten counts of possession of cocaine base; three counts of being a felon in possession of a firearm; one count of possessing an illegal firearm; and one count of controlling property used for the distribution of cocaine. -

City of Alexandria, Virginia

V I R G I N I A: IN THE CIRCUIT COURT FOR THE CITY OF ALEXANDRIA Plaintiff v. CASE NO. Defendants UNIFORM PRETRIAL SCHEDULING ORDER It is ORDERED that: I. Trial The trial date is with a jury at 10:00 a.m. The estimated length of trial is . Pretrial conference at 9:00 a.m. on . A pretrial conference is mandatory for all cases scheduled for more than 2 days and all Equitable Distribution cases. II. Discovery The parties shall complete discovery, including depositions, by 30 days before trial; however, depositions taken in lieu of live testimony at trial will be permitted until 15 days before trial. “Complete” means that all interrogatories, requests for production, requests for admissions and other discovery must be served sufficiently in advance of trial to allow a timely response at least 30 days before trial. Depositions may be taken after the specified time period by agreement of counsel of record or for good cause shown, provided however, that the taking of a deposition after the deadline established herein shall not provide a basis for continuance of the trial date or the scheduling of motions inconsistent with the normal procedures of the court. The parties have a duty to seasonably supplement and amend discovery responses pursuant to Rule 4:1(e) of the Rules of Supreme Court of Virginia. Seasonably means as soon as practical. No provision of this Order supersedes the Rules of Supreme Court of Virginia governing discovery. Any discovery motion filed shall contain a certification that counsel has made a good faith effort to resolve the matters set forth in the motion with opposing counsel. -

Defense Motions and Notices in Superior Court Phillip R. Dixon Jr

Defense Motions and Notices in Superior Court PHILLIP R. DIXON JR. Defense Motions and Notices in Superior Court Phillip R. Dixon Jr. Contents/Checklist Below is a table of contents of the motions and notices in this practice guide. Readers may want to make a copy of the table in each case and use it as a checklist of potential motions and notices to file. I. Principles for All Motions 3 II. Discovery Motions 5 A. Request for Voluntary Discovery/Motion for Discovery B. Motion to Compel Discovery C. Motion for Sanctions (Discovery or Other Violation) D. Motion for Prior Trial or Hearing Transcript E. Motion to Preserve Evidence F. Motion for Deposition III. Pre-Arraignment Motions 11 A. Generally B. Request for Arraignment C. Motion to Continue D. Motion for Change of Venue E. Motion to Dismiss for Improper Venue F. Motion for Special Venire G. Motion to Dismiss for Grand Jury Issues H. Motion to Dismiss for Defective Pleadings I. Motion to Strike Prejudicial or Inflammatory Language of Pleadings J. Motion for Bill of Particulars K. Motion for Joinder or Severance of Offenses and Co-Defendants IV. Other Pretrial Motions and Notices with Deadlines 21 A. Motion to Suppress B. Motion to Recuse Trial Judge C. Notice of Defenses D. Chapter 90 Notice and Demand E. Chapter 20 Notice and Demand F. Notice of Expert Testimony 1 Defense Motions and Notices in Superior Court (Dec. 2017) 2 G. Notice of Intent to Use Residual Hearsay H. Notice of Intent to Use Convictions Older than Ten Years V. Other Common Motions without Deadlines 30 A. -

![Cite As State V. Barnes, 149 Ohio Misc.2D 1, 2008-Ohio-5609.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7194/cite-as-state-v-barnes-149-ohio-misc-2d-1-2008-ohio-5609-2587194.webp)

Cite As State V. Barnes, 149 Ohio Misc.2D 1, 2008-Ohio-5609.]

[Cite as State v. Barnes, 149 Ohio Misc.2d 1, 2008-Ohio-5609.] THE COURT OF COMMON PLEAS CLERMONT COUNTY, OHIO THE STATE OF OHIO, : CASE NO. 2007 CR 0327 : 2007 CR 0417 Plaintiff, : : Judge Haddad v. : : BARNES, : DECISION/ENTRY : Defendant. : June 27, 2008 Donald White, Clermont County Prosecuting Attorney, and Scott Smith, Assistant Prosecuting Attorney, for plaintiff. Gary Rosenhoffer and Patrick Gregory, for defendant. HADDAD, Judge. {¶ 1} This matter was before the court on January 29, 2008, pursuant to a motion to consolidate filed by the state of Ohio, a motion to sever filed by the defendant, Clarence W. Barnes, and a motion for more specific bill of particulars filed by the defendant. A hearing was held on those motions and was continued in progress until March 7, 2008. On that date, the court heard three separate motions in limine filed by the defendant and a motion to compel filed by the defendant. The court then conducted a hearing on its own motion to clarify on May 20, 2008, and the state responded at a hearing on May 27, 2008. Upon hearing oral arguments on the motions, the court took the matter under advisement and now renders the following decision. FINDINGS OF FACT {¶ 2} The defendant, Clarence W. Barnes, was indicted on April 18, 2007, in case No. 2007 CR 0327, on nine counts of gross sexual imposition, a violation of R.C. 2907.05(A)(4). It is alleged that the defendant, on separate occasions during the time period of March 2006 through January 20, 2007, had sexual contact with another, not the spouse of the defendant, when the other person was less than 13 years of age, whether or not the defendant knew the person’s age. -

Motion in Limine to Exclude Lay and Expert Testimony

2:12-cr-20218-SFC-MKM Doc # 211 Filed 11/25/13 Pg 1 of 10 Pg ID 1058 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PLAINTIFF, CASE #: 12-20218 VS. HON. SEAN F. COX TIMOTHY IVORY CARPENTER DEFENDANT. AUSA Kenneth R. Chadwell (P39121) Harold Gurewitz (P14468) U.S. Attorney’s Office Counsel for Defendant 211 W. Fort Street, Suite 2001 Gurewitz & Raben, PLC Detroit, MI 48226 333 W. Fort Street, Suite 1400 (313) 226-9698 Detroit, MI 48226 (313) 628-4733 MOTION IN LIMINE TO EXCLUDE LAY AND EXPERT TESTIMONY Now comes Defendant Timothy Carpenter by his attorney, Harold Gurewitz, and respectfully requests, pursuant to FRE 403, 701, and 702, that this Court enter an order excluding expert testimony regarding the operation of cell towers. For his reasons, Defendant relies on the attached brief. Pursuant to LR 7.1, counsel for Defendant Carpenter sought concurrence on this motion. Concurrence was denied. Respectfully Submitted, GUREWITZ & RABEN, PLC By: s/Harold Gurewitz 333 W. Fort Street, Suite 1400 Detroit, MI 48226 (313) 628-4733 Email: [email protected] Date:November 22, 2013 Attorney Bar Number: 14468 2:12-cr-20218-SFC-MKM Doc # 211 Filed 11/25/13 Pg 2 of 10 Pg ID 1059 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PLAINTIFF, CASE #: 12-20218 VS. HON. SEAN F. COX TIMOTHY IVORY CARPENTER DEFENDANT. AUSA Kenneth R. Chadwell (P39121) Harold Gurewitz (P14468) U.S. Attorney’s Office Counsel for Defendant 211 W. -

Use of Motions in Limine in Civil Proceedings

Missouri Law Review Volume 45 Issue 1 Winter 1980 Article 11 Winter 1980 Use of Motions in Limine in Civil Proceedings Johnny K. Richardson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Johnny K. Richardson, Use of Motions in Limine in Civil Proceedings, 45 MO. L. REV. (1980) Available at: https://scholarship.law.missouri.edu/mlr/vol45/iss1/11 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Missouri Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Missouri School of Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Richardson: Richardson: Use of Motions in Limine in Civil Proceedings USE OF MOTIONS IN LIMINE IN CIVIL PROCEEDINGS Attorneys frequently find themselves in situations where the opposing counsel persistently solicits prejudicial evidence which, although logically relevant, is not legally relevant.' When this situation arises, the attorney is faced with the dilemma of either continually objecting to the evidence, thereby arousing the suspicions of the jury and creating additional preju- dice, or not objecting to the evidence, thereby waiving the right to -raise the issue in a motion for a new trial or on appeal.2 To avoid facing this double-edged sword, many experienced trial attorneys employ a relatively new procedural device: the motion in limine.3 This article is intended as a guide4 for the practicing attorney in the use of motions in limine in.civil practice.5 Although there are different versions of the motion in limine,. -

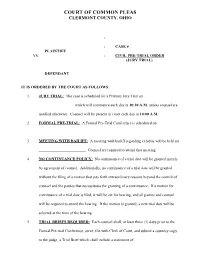

Judge Mcbride Sample Pre-Trial Order

COURT OF COMMON PLEAS CLERMONT COUNTY, OHIO : _________________________________ : CASE # ______________________ PLAINTIFF VS. : CIVIL PRE-TRIAL ORDER (JURY TRIAL) _________________________________ DEFENDANT IT IS ORDERED BY THE COURT AS FOLLOWS: 1. JURY TRIAL: The case is scheduled for a Primary Jury Trial on __________________ which will commence each day at 10:30 A.M. unless counsel are notified otherwise. Counsel will be present in court each day at 10:00 A.M. 2. FORMAL PRE-TRIAL: A Formal Pre-Trial Conference is scheduled on _________________________ 3. MEETING WITH BAILIFF: A meeting with bailiff regarding exhibits will be held on ________________________ Counsel are required to attend that meeting. 4. NO CONTINUANCE POLICY: No continuance of a trial date will be granted merely by agreement of counsel. Additionally, no continuance of a trial date will be granted without the filing of a motion that sets forth extraordinary reasons beyond the control of counsel and the parties that necessitates the granting of a continuance. If a motion for continuance of a trial date is filed, it will be set for hearing, and all parties and counsel will be required to attend the hearing. If the motion is granted, a new trial date will be selected at the time of the hearing. 5. TRIAL BRIEFS REQUIRED: Each counsel shall, at least three (3) days prior to the Formal Pre-trial Conference, serve, file with Clerk of Court, and submit a courtesy copy to the judge, a Trial Brief which shall include a statement of: (A) The issues involved; (B) A statement of the principles of law involved in the case supported by citations of appropriate authority; (C) An itemized list of the claimed special damages; (D) Any discovery difficulties; and (E) Whether a view is requested.