Disability and Euthanasia: the Case of Helen Keller and the Bollinger Baby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Educator's Guide

LIT TLE, BROWN AND COMPANY BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS Educator’s Guide | Ages: 6 & Up LittleBrownLibrary.com LBSchool LittleBrownSchool Helen’s Big World PRE-READING ACTIVITIES Anticipation Guide Step 1: Display the table below and ask students to decide as a group or individually whether the answer is true or false. If time permits, also ask students why they selected a particular answer. Step 2: After the completion of the story, refer back to the chart and ask students to answer the questions again. BEFORE STATEMENT AFTER Helen Keller was a famous woman who could not hear. Individuals who cannot see will never be able to write or read. Helen Keller traveled the world fighting for all people to have equal rights. Helen Keller had a teacher who worked with her while she was a child and an adult. Only elderly people can lose their ability to hear or see. Vocabulary Step 1: Introduce the key terms, definitions, and questions in the table below to help students better understand individuals with specific types of disabilities. Step 2: After introducing the vocabulary, make a connection to the text by presenting students with the following quote and question. Helen Keller said, “We do not think with eyes and ears, and our capacity for thought is not measured by five senses.” How do you think this quote from the text relates to the key terms in the table? continued on next page . Helen’s Big World QUESTIONS: Activating KEY TERMS DEFINITION Background Knowledge What is the difference between a People who can either see very person who wears glasses and a little or who have no vision at all. -

Timeline of Contents

Timeline of Contents Roots of Feminist Movement 1970 p.1 1866 Convention in Albany 1866 42 Women’s 1868 Boston Meeting 1868 1970 Artist Georgia O’Keeffe 1869 1869 Equal Rights Association 2 43 Gain for Women’s Job Rights 1971 3 Elizabeth Cady Stanton at 80 1895 44 Harriet Beecher Stowe, Author 1896 1972 Signs of Change in Media 1906 Susan B. Anthony Tribute 4 45 Equal Rights Amendment OK’d 1972 5 Women at Odds Over Suffrage 1907 46 1972 Shift From People to Politics 1908 Hopes of the Suffragette 6 47 High Court Rules on Abortion 1973 7 400,000 Cheer Suffrage March 1912 48 1973 Billie Jean King vs. Bobby Riggs 1912 Clara Barton, Red Cross Founder 8 49 1913 Harriet Tubman, Abolitionist Schools’ Sex Bias Outlawed 1974 9 Women at the Suffrage Convention 1913 50 1975 First International Women’s Day 1914 Women Making Their Mark 10 51 Margaret Mead, Anthropologist 1978 11 The Woman Sufferage Parade 1915 52 1979 Artist Louise Nevelson 1916-1917 Margaret Sanger on Trial 12 54 Philanthropist Brooke Astor 1980 13 Obstacles to Nationwide Vote 1918 55 1981 Justice Sandra Day O’Connor 1919 Suffrage Wins in House, Senate 14 56 Cosmo’s Helen Gurley Brown 1982 15 Women Gain the Right to Vote 1920 57 1984 Sally Ride and Final Frontier 1921 Birth Control Clinic Opens 16 58 Geraldine Ferraro Runs for VP 1984 17 Nellie Bly, Journalist 1922 60 Annie Oakley, Sharpshooter 1926 NOW: 20 Years Later 1928 Amelia Earhart Over Atlantic 18 Victoria Woodhull’s Legacy 1927 1986 61 Helen Keller’s New York 1932 62 Job Rights in Pregnancy Case 1987 19 1987 Facing the Subtler -

Multiple Choice-‐ Please Circle the Correct Answer. Fill in the Blank-‐

Name ___________________________________________________________ Directions: The second graders spent sometime during Social Studies learning about six famous Americans. Each student made a book about these six famous Americans and then the class made a test together. See how well you know these famous Americans. Try your best! Multiple Choice- Please circle the correct answer. 1. Who helped free African American slaves? A. Martin Luther King Jr. B. Abraham Lincoln C. George Washington D. Jackie Robinson 2. Who helped Helen Keller? A. Bob Sullivan B. Grace Sullivan C. Annie Sullivan D. Lucy Sullivan 3. Who joined the army when they were young? A. Helen Keller B. Jackie Robinson C. Martin Luther King Jr. D. Bob Washington 4. Who did Martin Luther King Jr. marry? A. Annie Sullivan B. Harriet Tubman C. Helen Keller D. Coretta Scott King Fill in the Blank- Please fill in the blank with the correct answer. 5. George Washington was a ______________________________ when he was young. 6. Abraham Lincoln was the ______________________________ president of the United States of America. 7. George Washington was nicknamed ___________________________________________________________________. 8. Helen Keller was ______________________________ and __________________________________. 9. Jackie Robinson played baseball for the _________________________________ Dodgers. True or False- Please circle True or False for each statement. 10. True or False Susan B. Anthony is on a one-dollar bill. 11. True or False Abraham Lincoln gave a famous speck called “I have a Dream.” 12. True or False Susan B. Anthony fought for women’s right to vote. 13. True or False Abraham Lincoln is nicknamed “Father of Our Country.” Short Answer- Please answer the questions in complete sentences. -

Parades, Pickets, and Prison: Alice Paul and the Virtues of Unruly Constitutional Citizenship

PARADES, PICKETS, AND PRISON: ALICE PAUL AND THE VIRTUES OF UNRULY CONSTITUTIONAL CITIZENSHIP Lynda G. Dodd* INTRODUCTION: MODELS OF CONSTITUTIONAL CITIZENSHIP For all the recent interest in “popular constitutionalism,” constitutional theorists have devoted surprisingly little attention to the habits and virtues of citizenship that constitutional democracies must cultivate, if they are to flourish.1 In my previous work, I have urged scholars of constitutional politics to look beyond judicial review and other more traditional checks and balances intended to prevent governmental misconduct, in order to examine the role of “citizen plaintiffs”2 – individuals who, typically at great personal cost in a legal culture where the odds are stacked against them, attempt to enforce their rights in * 1 For some exceptions, see Walter F. Murphy, CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY: CREATING AND MAINTAINING A JUST POLITICAL ORDER (2007); JAMES E. FLEMING, SECURING CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY: THE CASE FOR AUTONOMY (2006); Wayne D. Moore, Constitutional Citizenship in CONSTITUTIONAL POLITICS: ESSAYS ON CONSTITUTIONAL MAKING, MAINTENANCE, AND CHANGE (Sotirios A. Barber and Robert P. George, eds. 2001); Paul Brest, Constitutional Citizenship, 34 CLEV. ST. L. REV. 175 (1986). 2 Under this model of citizenship, the citizen plaintiff is participating in the process of constitutional checks and balances. That participation can be described in terms of “enforcing” constitutional norms or “protesting” the government’s departure from them. The phrase “private attorneys general” is the traditional term used to describe citizen plaintiffs. See, e.g., David Luban, Taking Out the Adversary: The Assault on Progressive Public Interest Lawyers, 91 CAL. L. REV. 209 (2003); Pamela Karlan, Disarming the Private Attorney General, 2003 U. -

Writing: Mrs. Zodo

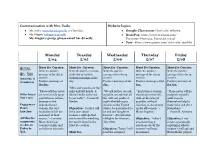

Communication with Mrs. Zodo Website logins ● Ms. Zodo: [email protected] or ClassDojo ● Google Classroom-Class code: nfdwiw6 ● Ms. Hagan: [email protected] ● BrainPop- https://www.brainpop.com/ Ms. Hagan’s group, please email her directly. Username: Peterson2. Password: school ● Epic- .https://www.getepic.com/ class code: ujq1860 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday 5/04 5/05 5/06 5/07 5/08 Must Do Cursive: Must Do Cursive: Must Do Cursive: Must Do Cursive: Must Do Cursive: Writing: Write the positive Write the positive message Write the positive Write the positive Write the positive message of the day in of the day in cursive. message of the day in message of the day in message of the day in Mrs. Zodo cursive. Positive message of the cursive. cursive. cursive. (total time is 30 minutes) Positive message of day: Positive message of the Positive message of the Positive message of the day: day: day: the day: "Men and women are like "The world has never right and left hands; it "We ask justice, we ask “ Each time a woman “There never will be Office hours: yet seen a truly great doesn't make sense not equality, we ask that all stands up for herself, complete equality 9am-11am and virtuous nation, to use both." - Jeannette the civil and political without knowing it until women because in the Rankin rights that belong to possibly, without themselves help to Engagement degradation of citizens of the United claiming it, she stands make laws and elect Hours: women, the very Objective: Today I will States, be guaranteed to up for all women.” - lawmakers.” 1pm-3pm fountains of life are list 3 facts about us and our daughters Maya Angelou. -

Helen Keller

Helen Keller 1880-1968 Early Life ● Helen Keller was born in June of 1880 in Tuscumbia, Alabama ○ Although she had been born hearing, when she was 19 months old a high fever left Helen Blind and Deaf ● While she was growing up, Keller’s parents indulged her, leading to her being a disobedient child. This was added to by her lack of the ability to communicate, causing her to become frustrated and have many outbursts. ● In 1887, Anne Sullivan entered Keller’s life as her teacher. ○ Anne was able to break through Helen’s barriers by teaching her fingerspelling in American Sign Language. It is said that Helen was feeling water through her fingers in one hand while Anne was fingerspelling the word W-A-T-E-R in the other and things clicked. Expanding Knowledge ● After Helen soaked in information to communicate full sentences using the hand alphabet, she tackled the task of learning Braille, a language consisting of raised dots that one can read by feeling. ● Keller also successfully learned speech, along with becoming an accomplished typist. ● Through all of her studies, including Helen attending the Ivy League school Radcliff, Anne Sullivan was there. ○ Helen became the first Deaf-Blind person to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree Leaving an Impact ● After graduating in 1904, Keller became a world traveler, lecturing, writing, fundraising and raising awareness about issues concerning the disabled, poor and oppressed. ○ She also visited wounded soldiers from World War II, encouraging those who lost their sight in battle to recognize that they could still live a full life. -

Alice Paul Keeps Fighting

Success and Resistance - Alice Paul Keeps Fighting As Alice Paul, Lucy Burns and their colleagues continue the suffragist fight, they encounter resistance. It isn't just men who disapprove of their efforts. Even some American women are not convinced the suffragists are right. Despite the opposition, the suffragists are undaunted. The parade—on March 13, 1913—is a very serious step forward in gathering much-needed publicity for the cause. Even Helen Keller attends the event: But to the women, the event was very serious. Helen Keller “was so exhausted and unnerved by the experience in attempting to reach a grandstand . that she was unable to speak later at Continental hall [sic ].” Two ambulances “came and went constantly for six hours, always impeded and at times actually opposed, so that doctor and driver literally had to fight their way to give succor to the injured.” One hundred marchers were taken to the local Emergency Hospital. Before the afternoon was over, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, responding to a request from the chief of police, authorized the use of a troop of cavalry from nearby Fort Myer to help control the crowd. Despite enormous difficulties, many of those in the parade completed the route. When the procession reached the Treasury Building, one hundred women and children presented an allegorical tableau written especially for the event to show “those ideals toward which both men and women have been struggling through the ages and toward which, in co-operation and equality, they will continue to strive.” The pageant began with “The Star Spangled Banner” and the commanding figure of Columbia dressed in national colors, emerging from the great columns at the top of the Treasury Building steps. -

The Margaret Sanger Papers Illuminate the Historical Roots of the Birth Control Movement

AN ESSAY The Margaret Sanger Papers Illuminate the Historical Roots of the Birth Control Movement Professor Esther Katz, founder and director of the Margaret Sanger Papers, answered some questions about the digitization of the Margaret Sanger Papers in ProQuest History Vault, and the extraordinary value of this primary source material for researchers. proquest.com How is studying Margaret Sanger’s career relevant to us today? Why do you think it is important for students and researchers to have access to this content? Margaret Sanger was one of the most controversial figures in her lifetime and continues to be so today. Contentious, often inaccurate, and usually politically motivated assessments of her work, both from the Right and the Left, have appeared in scholarly and popular literature, in newspaper columns and on the Internet. Recent film documentaries dramatizing Sanger’s life attest to the growing interest in her role in American social history. This interest in Sanger and the historical and social roots of the birth control movement has been intensified by recent debates over abortion rights, sex education, contraceptive provision by schools and new birth control methods, not to mention growing concerns over attempts to limit welfare births and global population control policies. Because Sanger herself instigated public discourse on many of these issues, for which she has been both vilified and praised, demand for access to her papers and for new interpretations of her life and work has dramatically increased.1 With mixed results, various biographies and monographs have given us divergent accounts of Sanger’s life and her impact on American society. -

Pub Date Note Available From

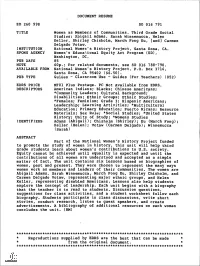

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 260 998 SO 016 791 TITLE Women as Members of Communities. Third Grade Social Studies: Abigail Adams, Sarah Winnemucca, Helen Keller, Shirley Chisholm, March Fong Eu, [and] Carmen Delgado Votaw. INSTITUTION National Women's History Project, Santa Rosa, CA. SPONS AGENCY Women's Educational Equity Act Program (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 85 NOTE 60p.; For related documents, see SO 016 788-790. AVAILABLE FROM National Women's History Project, P.O. Box 3716, Santa Rosa, CA 95402 ($6.50). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS American Indians; Blacks; Chinese Americans; *Community. Leaders; Cultural Background; Disabilities; Ethnic Groups; Ethnic Studies; *Females; Feminism; Grade 3; Hispanic Americans; Leadership; Learning Activities; *Multicultural Education; Primary Education; Puerto Ricans; Resource Materials; Sex Role; *Social Studies; *United States History; Units of Study; *Womens Studies IDENTIFIERS Adams (Abigail); Chisholm (Shirley); Eu (March Fong); Keller (Helen); Votaw (Carmen Delgado); Winnemucca (Sarah) ABSTRACT Part of the National Women's History Project funded to promote the study of women in history, this unit will help third grade students learn about women's contributions to U.S. society. Equity cannot be achieved until equality is expected and until the contributions of all women are understood and accepted as a simple matter of fact. The unit contains six lessons based on biographies of women, past and present. They were chosen to represent the many ways women work as members and leaders of their communities. The women are Abigail Adams, Sarah Winnemucca, March Fong Eu, Shirley Chisholm, and Carmen Delgado Votaw, representing major ethnic groups, and Helen Keller, representing disabled Americans. -

HIS122 Women in American History Credit Hours: 4 Quarter Hours Method of Delivery: Campus

MIDSTATE COLLEGE 411 W. NORTHMOOR RD. PEORIA, IL 61614 (309) 692-4092 (800) 251-4299 1996 Course number & Name: HIS122 Women in American History Credit hours: 4 quarter hours Method of Delivery: Campus Course Description: A study of America with emphasis on the importance of women of the period who have been instrumental in the shaping of America’s past, present, and future. Prerequisites: Text(s) & Manual(s): A History of Women in America Author(s): Carol Hymowitz and Michaele Weissman Publisher: Bantam Books ISBN: Materials needed for this course: Additional Supplies: Hardware/Software and Equipment: Topics: Learning Objectives: Upon completion of this course, the student will be able to: 1. Identify women who held historical, political, industrial, and social positions in the shaping of America. 2. Understand the evolution of the rights of women and the laws pertaining to them. 3. Formulate informed opinions on the roles of men and women in American society. Midstate Grading scale: 90 - 100 A 80 - 89 B 70 - 79 C 60 - 69 D 0 - 59 F Midstate Plagiarism Policy: Matters related to academic honesty or contrary action such as cheating, plagiarism, or giving unauthorized help on examinations or assignments may result in an instructor giving a student a failing grade for that academic effort and also recommending the student be given a failing grade for the course and/or be subject to dismissal. Plagiarism is using another person’s words without giving credit to the author. Original speeches, publications, and artistic creations are sources for research. If you use the author’s words in your papers or assignments, you must acknowledge the source. -

Helen Keller's Struggle

HELEN KELLER’S STRUGGLE IN THE STORY OF MAY LIFE ABSTRACT Eka Ardhinie One of the literary works is novel. In the novel we can find many kinds of character. Sri Hartati This research aims to find out the characteristics of Helen Keller by using psychological approach and to describe the factors influence Helen Keller to struggle in obtaining the equal confession as usual human. This research used Fakultas Sastra qualitative method in analyzing the data. The data is taken from Helen Keller’s Universitas Gunadarma Novel “The Story of My Life” and in the form of quotation from novel that related to Helen Keller’s characters. The result of this research are the characteristics of [email protected] Helen Keller in term of angry, naughty, curiosity, struggle, eager, clever, dilligent, [email protected] care, confident, brave, independent. There are also some factors that influence the characteristics of Helen Keller, such as: Influence from family, teacher and famous people. Key Words: Characters, Struggles, Factor Influences. INTRODUCTION and the behavior within the novel. The fiction, the heroes and villains, allies and source of data in this research is a novel enemies, love intersts and comic relief Literary often describes about human’s entitled “The Story of My Life” written by (Mc Laughlin, 1989:375). According to life that related to culture, religion, social, Helen Keller in 1903 as the primary data. David Grambs, Character is a portrayal moral and so on. Almost the whole literary or description so as to distinguish; the give impact to the reader when they have THEORETICAL REVIEW creation or representation of character in finished to read. -

JJ Lankes Papers, 1907-1988

1 of 9 J.J. Lankes Papers, 1907-1988 (bulk 1922-1934, 1942) Administration Information Creator J.J. Lankes RBR Illus. L2 1907 Extent 2 letter-size document cases, 1 legal-size document case. 1.5 linear feet. Abstract A collection consisting primarily of letters sent to J.J. Lankes, renowned woodcut artist. The letters detail business and personal events, and correspondents include Charles Burchfield, Helen Keller, William J. Schwanekamp, and Robert Frost. Terms of Use The J.J. Lankes Papers is open for research. Reproduction of Materials See librarian for information on reproducing materials from this collection, including photocopies, digital camera images, or digital scans, as well as copyright restrictions that may pertain to these materials. Acquisition The J.J. Lankes Papers were bequeathed to the Rare Book Room of the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library through the will of Julius Bartlett Lankes (J.B. Lankes), son of J.J. Lankes, in 2010. Biographical Note Julius John Lankes, known as J.J. Lankes (1884–1960), was an American woodcut artist and illustrator. The majority of his work features nature scenes of the eastern United States. As an artist, he was friends with a number of poets and writers who commissioned work for publications, including Robert Frost, Beatrix Potter and Sherwood Anderson. Lankes was born in Buffalo and graduated from the Buffalo Commercial and Electro-Mechanical Institute in 1902. It was only after attending the Art Students League of Buffalo and the School of the Museum of Fine Arts that he created his first woodcut. In 1910 Lankes formed the Saturday 2 of 9 Sketch Club with other students from the Albright Art Academy, including lifelong friend William Schwanekamp.