OHRJ-Vol II 3&4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXI NO. 5 DECEMBER - 2014 MADHUSUDAN PADHI, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary RANJIT KUMAR MOHANTY, O.A.S, ( SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Shrikshetra, Matha and its Impact Subhashree Mishra ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 India International Trade Fair - 2014 : An Overview Smita Kar ... 7 Mo Kahani' - The Memoir of Kunja Behari Dash : A Portrait Gallery of Pre-modern Rural Odisha Dr. Shruti Das ... 10 Protection of Fragile Ozone Layer of Earth Dr. Manas Ranjan Senapati ... 17 Child Labour : A Social Evil Dr. Bijoylaxmi Das ... 19 Reflections on Mahatma Gandhi's Life and Vision Dr. Brahmananda Satapathy ... 24 Christmas in Eternal Solitude Sonril Mohanty ... 27 Dr. B.R. Ambedkar : The Messiah of Downtrodden Rabindra Kumar Behuria ... 28 Untouchable - An Antediluvian Aspersion on Indian Social Stratification Dr. Narayan Panda ... 31 Kalinga, Kalinga and Kalinga Bijoyini Mohanty .. -

Temples Name Sates Vaishno Devi Jammu & Temple, Kashmir Dedicated to Shakti, Mata Rani Badrinath Temple Uttarakhand Kedarnath Temple Uttarakhand

Temples Name Sates Vaishno Devi Jammu & Temple, Kashmir Dedicated to Shakti, Mata Rani Badrinath Temple Uttarakhand Kedarnath Temple Uttarakhand Golden Temple Amritsar, Punjab Markandeshwar Temple Haryana Hadimba devi Temple Himachal Pradesh Laxminarayan Temple ( New Delhi Birla Mandir ) Dilwara Temple Mount Abu, Rajasthan Kashi Vishwanath Temple- Varanasi, Uttar Dedicated to Lord Ganesha Pradesh Swaminarayan Akshardhan Delhi Temple Mahabodhi Temple Bodhgaya , Bihar Dakshnineswar kali Temple Kolkata Jagannath Temple - Puri, Odisha Dedicated to Jagannath God Kandariya Mahadev Madhya Temple- Part of Pradesh Khajuraho Temple Somnath Gujarat (Saurashtra ) Temple Siddhivinayak Temple- Located in Dedicated to Lord Ganesha Prabhadevi, Mumbai Maharashtra Balaji Venkateshwara Andhra Swamy Temple- Dedicated Pradesh to Lord Venkateshwara Lord Karnataka kalabhairah wara Temple Shi Dharmasthala Karnataka Manjunatheswara Temple Shi Dharmasthala Karnataka Manjunatheswara Temple Mureshwar Temple Karnataka Virupaksha Temple Karnataka Gomateshwara Bahubali Karnataka Temple Nataraja Temple- Tamil Nadu Dedicated to Lord Shiva Brihadeshwara Temple Thanjavur,Ta mil Nadu Jumbukeshwarar Temple Tamil Nadu Ranganathaswamy Temple- Tamil Nadu Dedicated to Lord Shiva Ekambareswarar Temple Kanchipuram, Tamil Nadu Sripuram Golden Temple- Vellore, Tamil Dedicated to Lord Shiva Nadu Padmanabhaswa Kerala my Temple Richest Temple of the world Sabarimala Temple Kerala Sukreswar Temple- Dedcated Assam to Lord Shiva Kamakhya Temple Assam Angkor Wat Temple- Largest Cambodia -

Buddhism During the Bhaumakara Period: a Case of Study on Social Life in Odisha

International Journal of Social Science Citation: IJSS: 8(1): 11-18, March 2019 DOI: 10.30954/2249-6637.01.2019.3 ©2019 New Delhi Publishers. All rights reserved Buddhism during the Bhaumakara Period: A case of study on Social life in Odisha Manas Kumar Rout History Department, Ravenshaw University, Cuttack, Odisha, India Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT In this paper I try to highlight on the Buddhist faith and believe in ancient period. Especially Bhaumakara dynasty regime what is the social condition of the society specific reference to Buddhism. Many of the inscriptional and literary sources tell about social system of Odisha during the Bhaumakara Period. Many of the scholars study it but anybody not clearly mention which of the question raise this paper. The Bhaumakara grant tells various titles like Paramsaugata, Parambhattarak, Tathagata etc¹ but the scholar and historian analysis it the Bhuamakaras are followed and patronized Buddhism but many of the land grant goes to Brahmans. It is clear that the Brahmans are staying and maintain high class in the society. If In Odisha the Brahman are lived with a high standard living style so after the Bhaumakara fallen the Somyavamsi king Yayati I why calling the ten thousand Brahman from the Kanauj²? Another question is that if he calling for the Aswamedha sacrifice then why he donate village for the permanent settlement? The Study of Buddhist literature says that the One Buddhist monk defeated to Brahman on the Gospel (Sastra) discussion. After this gospel discussion five hundred Brahman converted from Brahmanical faith to Buddhist faith³. This paper is the based on the study of literarily and inscription sources and to get the answer to cast system during the period and increasing of the Buddhist follower. -

Defaulter-Private-Itis.Pdf

PRIVATE DEFAULTER ITI LIST FOR FORM FILL-UP OF AITT NOVEMBER 2020 Sl. No. District ITI_Code ITI_Name 1 ANGUL PR21000166 PR21000166-Shivashakti ITC, AT Bikash Nagar Tarang, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 2 ANGUL PR21000192 PR21000192-Diamond ITC, At/PO Rantalei, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 3 ANGUL PR21000209 PR21000209-Biswanath ITC, At-PO Budhapanka Via-Banarpal, Anugul, Odisha, - 759128 4 ANGUL PR21000213 PR21000213-Ashirwad ITC, AT/PO Mahidharpur, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 5 ANGUL PR21000218 PR21000218-Gayatri ITC, AT-Laxmi Bajar P.O Vikrampur F.C.I, Anugul, Odisha, - 759100 6 ANGUL PR21000223 PR21000223-Narayana Institute of Industrial Technology ITC, AT/PO Kishor, Anugul, Odisha, -759126 7 ANGUL PR21000231 PR21000231-Orissa ITC, AT/PO Panchamahala, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 8 ANGUL PR21000235 PR21000235-Guru ITC, At.Similipada, P.O Angul, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 9 ANGUL PR21000358 PR21000358-Malayagiri Industrial Training Centre, Batisuand Nuasahi Pallahara, Anugul, Odisha, -759119 10 ANGUL PR21000400 PR21000400-Swami Nigamananda Industrial Training Centre, At- Kendupalli, Po- Nukhapada, Ps- Narasinghpur, Cuttack, Odisha, -754032 11 ANGUL PR21000422 PR21000422-Matrushakti Industrial Training Institute, At/po-Samal Barrage Town ship, Anugul, Odisha, -759037 12 ANGUL PR21000501 PR21000501-Sivananda (Private) Industrial Training Institute, At/Po-Ananda Bazar,Talcher Thermal, Anugul, Odisha, - 13 ANGUL PU21000453 PU21000453-O P Jindal Institute of Technology & Skills, Angul, Opposite of Circuit House, Po/Ps/Dist-Angul, Anugul, Odisha, -759122 14 BALASORE -

The Temple Architecture in Odisha

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review The Hindu temple architecture reflects a synthesis is concentrated in the city of Bhubaneswar where of arts, the ideals of religion, beliefs, values and there are over thirty of them. the way of life cherished under Hinduism. The temple is a place for pilgrimage. All the cosmic The main temples of this style consist of elements that create and celebrate life in Hindu the Lingaraja Temple at Bhubaneswar th pantheon are present in a Hindu temple from fire (11 century), the Jagannath temple at Puri th to water, from images of nature to deities, from (12 century) the Great Sun Temple at Konark the feminine to the masculine, from karma to (13th century), Rajarani Temple (10th century), artha. The form and meanings of architectural Mukteswar (10th Century), Parshuram Temple elements in a Hindu temple are designed to (8th Century) etc. function as the place where it is the link between The Kanlingan style consists of three man and the divine, to help his progress to spiritual distinct types of temples Rekha Deula, Pidha knowledge and truth, his liberation is called Deula and Khakhara Deula. The former two are Moksha. associated with Vishnu, Surya and Shiva temples The Temple Architecture in Odisha Sujata Routray The Indian temples are broadly divided while the third is mainly with Chamunda and Durga into Nagara, Vesara, Dravida and Gadag styles temples. The Rekha Deula and Khakhara Deula of architecture. However the temple architecture houses the sanctum sanctorum while the Pidha of Odisha corresponds to altogether a different Deula constitutes outer dancing and offering halls. -

History of Medieval Odisha - Religious Perspective

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review he history of religion in medieval Odisha from controversies to establish their own theories. T12th Century AD onwards is of immense Ramanuja was the Alvar, who was the successor importance. Different religious cults flourished side of Yamunamuni. The philosophy of Ramanuja is by side and every faith had its culmination in the called Visistadvaita. From the commentary on cult of Jagannath. There are three distinct features. Brahmasutra, the keynote of his entire work can First, the continuance of the cosmopolite be summed up. Himself a devotee of Visnu, he homogeneity in the midst of diversity. Second, derived his metaphysical doctrines from the predominance and supremacy of Vaisnavism as Upanisads and Brahmasutras. R. G. Bhandarkar a major religion of Odisha as well as the erection opines that, the Vaisnavism of Ramanuja is the of remarkable religious structures. Third, the Vasudevism combined with the Narayaniya and inspired influence of the saints of Odisha. The role Visnu elements. of Ramanuja and Chaitanya created a magnificent chapter of dedication and devotion in Odisha. Most of the historians agree that Ramanuja visited Odisha between 1122 to 1137 Medieval period in Odisha was a great AD. His visit to Odisha was a great event indeed. age of religious achievements. The suitable P. Mukherjee states that Ramanuja visited Puri History of Medieval Odisha - Religious Perspective Rajashree Patnaik geographical location and the favourable cultural atmosphere of Odisha have provided opportunity to preach his faith, as a part fulfillment of his since ancient times for the growth and progress mission. The religious history of Odisha reveals of various religious cults like; Buddhism, Jainism, the fact that, popularity of any religion used to Saivism, Saktism and Vaisnavism. -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

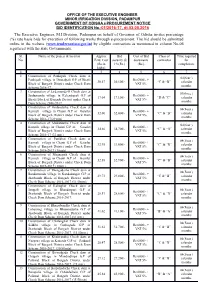

BID IDENTIFICATION No.-01/2016-17, Dt.03.05.2016 The

OFFICE OF THE EXECUTIVE ENGINEER MINOR IRRIGATION DIVISION, PADAMPUR GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA e - PROCUREMENT NOTICE BID IDENTIFICATION No.- 01/2016-17, dt.03.05.2016 The Executive Engineer, M.I.Division, Padampur on behalf of Governor of Odisha invites percentage (%) rate basis bids for execution of following works through e-procurement. The bid should be submitted online in the website ( www.tendersorissa.gov.in ) by eligible contractors as mentioned in column No-06 registered with the state Governments. Sl. Name of the project & location Approx Bid Cost of Bid Class of Time required No. Estd. Cost security @ documents contractor for (Rs.in 1%(Rs.) (Rs.) completion. lakhs) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 Construction of Pankipali Check dam at 04(four ) Pankipali village in Dumalpali G.P of Bhatli Rs.6000/- + 30.57 30,600/- “C & “B” calendar Block of Bargarh District under Check Dam VAT 5% months Scheme 2016-17. 2 Construction of Jardamunda-II Check dam at 03(three ) Jardamunda village in Kelendapali G.P of Rs.6000/- + 17.04 17,100/- “D & “C” calendar Bhatli Block of Bargarh District under Check VAT 5% months Dam Scheme 2016-2017. 3 Construction of Godendarha Check dam at 04(Four ) Kermeli village in Chanti G.P of Gaisilet Rs.6000/- + 32.00 32,000/- “C” & “B” calendar Block of Bargarh District under Check Dam VAT 5% months Scheme 2016-17(29 mtr) 4 Construction of Mukutdarha Check dam at 04(four ) Kermeli village in Chanti G.P of Gaisilet Rs.6000/- + 34.66 34,700/- “C” & “B” calendar Block of Bargarh District under Check Dam VAT 5% months Scheme 2016-17 (32 mtr.). -

List of Colleges Affiliated to Sambalpur University

List of Colleges affiliated to Sambalpur University Sl. No. Name, address & Contact Year Status Gen / Present 2f or Exam Stream with Sanctioned strength No. of the college of Govt/ Profes Status of 12b Code (subject to change: to be verified from the Estt. Pvt. ? sional Affilia- college office/website) Aided P G ! tion Non- WC ! (P/T) aided Arts Sc. Com. Others (Prof) Total 1. +3 Degree College, 1996 Pvt. Gen Perma - - 139 96 - - - 96 Karlapada, Kalahandi, (96- Non- nent 9937526567, 9777224521 97) aided (P) 2. +3 Women’s College, 1995 Pvt. Gen P - 130 128 - 64 - 192 Kantabanji, Bolangir, Non- W 9437243067, 9556159589 aided 3. +3 Degree College, 1990 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 055 128 - - - 128 Sinapali, Nuapada aided (03-04) 9778697083,6671-235601 4. +3 Degree College, Tora, 1995 Pvt. Gen P-2005 - 159 128 - - - 128 Dist. Bargarh, Non- 9238773781, 9178005393 Aided 5. Area Education Society 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2002 12b 066 64 - - - 64 (AES) College, Tarbha, Aided Subarnapur, 06654- 296902, 9437020830 6. Asian Workers’ 1984 Pvt. Prof P 12b - - - 64 PGDIRPM 136 Development Institute, Aided 48 B.Lib.Sc. Rourkela, Sundargarh 24 DEEM 06612640116, 9238345527 www.awdibmt.net , [email protected] 7. Agalpur Panchayat Samiti 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 003 128 64 - - 192 College, Roth, Bolangir Aided 06653-278241,9938322893 www.apscollege.net 8. Agalpur Science College, 2001 Pvt. Tempo - - 160 64 - - - 64 Agalpur, Bolangir Aided rary (T) 9437759791, 9. Anchal College, 1965 Pvt. Gen P 12 b 001 192 128 24 - 344 Padampur, Bargarh Aided 6683-223424, 0437403294 10. Anchalik Kishan College, 1983 Pvt. -

Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change

INTRODUCTION The Indian Parliament composed of the Lower House of the People (Lok Sabha) and the Upper House of States (Rajya Sabha). It is the highest legislative body in the country and creates a platform for voicing opinions on important matters of the country. The Members belong to different States/Union Territories or are experts in the fields of scientific, cultural and social issues. In 1984, ENVIS Centre 07 of the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, Government of India, was established in WWF-India to handle environment-related information i.e parliament and Environment and NGO and Environment. A substantial amount of environment-related information is exchanged in both the Houses of Parliament in response to queries and call attention notices raised by the Members. The Centre has been actively monitoring Parliamentary discussions on environmental issues for more than two and half decade. Such information relates largely to development activities with environmental implications, other relevant programmes, legislation, policies, etc. This information has been compiled and published by the Centre in separate volumes on yearly basis. The report enclosed the compilation of the current Budget Session 2014, a total number of 405 Parliament Questions pertaining to various aspects of environment were answered by the Ministry of Environment and Forests and Climate Change (261 questions in the Lok Sabha, out of which 25 were starred and 261 were un- starred. A total of 144 questions were asked in the Rajya Sabha, out of which 18 were starred and 126 were un-starred). The questions covered a wide range of environmental issues, with which the Ministry is concerned. -

1 COVER- INNER Final Rajeev.Pmd

CLASSICAL ODIA Document Prepared Under the overall Supervision of Dr. Debi Prasanna Pattanayak (Padmashree) B.A. (Hons), M.A.in Odia, Utkal University (Gold Medalist). M.A. in Linguistics, Pune University. Diploma in French, Viswabharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal Ph.D. in Linguistices, cornall, USA. D.litt(Honoris causa) SOA University, Bhubaneswar. Professer Emeritus: Pune University, Utkal University of Culture, Founder Director: Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, Additional Secretary (Retd.): MHRD, Government of India, Chairman: Institute of Odia Studies and Research Subrat Kumar Prusty (UGC-NET-SRF) B.A. (Hons), M.A.(Odia) Ravenshaw University, LLB, Madhusudan Law Collage, Ph.D,(Cont.) P.G. Deptt. Of Odia, Utkal University, Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar Editor- Civil Service Pathi Member secretary: Institute of Odia Studies and Research Director: IAS Pathi KIS Foundation D-82, Maitri Vihar, Chandrasekharpur Bhubaneswar, Odisha, 755001 © Institute of Odia Studies and Research Published by KIS Foundation D-82, Maitri Vihar, Chandrasekharpur Bhubaneswar, Odisha 755001 Email : [email protected] Tel. : 0674-2300969 Edition : 2013 ISBN : 978-81-925616-3-9 Price : ` 1500 Printed at Vikas Printers, Naveen Shahdara, Delhi 110032 Tel. 22822514 Foreword Odia is one of the most ancient languages of India. Eminent linguists and scholars like John Beams, G.A Grierson, L.S.S O Malley, Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, Pandit Nilakantha Das, John Boulton, Dr. D.P. Pattnayak, Dr. Bijaya Prasad Mahapatra and others have time and again argued in favour of the antiquity of Odia language. Odisha is the only state, where discovered three types of Brhami script like -PreBrahmi, Brahmi & Post Brahmi-. The Indian script ‘o’ (tha) was discovered from yogimatha rock painting of Nuapada district. -

Unrecognized Political Parties- Allotment of Common Symbol Under Para 1OB of the Election Symbols (Reservation and Allotment)

JJuRGENTjJ ~-Bi?-1 fa! cl f=q cil Q G I f£I cb IJ.1, esc=cft -l-1 JI a,• ~ II a1 ifl cb., ~-lIcit I a-i 51 Icl i!.I q R-c1 -l., -lI i!.1 ~-l ~- 2236685- ~q~- 0771-2236684 email :- [email protected] w. a 9 ,ffl"R:"112 a 1 1 -2 a 1 4/ FJ9-3eo ~, RePafa 1 3ITT.1cf51 ~, -2.-i-2.-t en e1 Pai c1 re o1 ~, -l-f cH M (30 cJT O ) P.jq1S1~:-c11cf5-2-ta-rr "' 3na, ti!ailcl-2 o 1 4, 3HcirJI"' m ........-liui~-2."S<-r-cb~c.--.-a(::,,..., 3-lcf1l~a, "Q"Tl<f ~ cffi" 3il csi IB<i \.I cfl cf5 3il csi Cai cf5T \.I fa~ j ~ al Icl tj_ I c1"' 1 cb-2.-13-IT 3na=f ti!ai , c1- 2 o 1 4 cf.> ~ -lM -2."S<c{?a 3-t a-i 1~ a , "!l"l1<f ~ cffi" 3TI"-lcf Pai a f=q ai 3-11 ci, J, m \.I cfl cf5 3-11 csi cai cBT vT$ ~ , \.I cfl cf5 3-11 csi cai cf.> ~a -a1" 56/Symbol/2014/PPS-II/Vol. I, rec:iiicf5 2 7 R-2.-tcMJ-l, 2 o 1 3, "Q?I" -2-i&-11 56/Symbol/2014/PPS-II/Vol. II, Rc:iiicf5 o 3 o16-ic1:fl, 2 o 1 4, "Q?I" -2-1&-11 56/Symbol/2014/PPS-II/Vol. Ill, Raiicf5 1 o o1aic1:fl, 2 o 1 4"Q?I" -2-i&-11 56/Symbol/2014/PPS-II/Vol.