Searching for Margaret

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reunion Booklet

Class of 1957 60th Reunion APRIL 27-30, 2017 1 1 USMA Class of 1957 60th Reunion West Point, New York elcome to the 60th Reunion of the Class of 1957. This booklet provides an W update to changes regarding facilities at our alma mater since we graduated. We all appreciate how fortunate we are to be associated with such an outstanding and historic institution as this—“Our” United States Military Academy. In this booklet you will find a copy of our Reunion schedule, photos and information about new and modernized facilities on our West Point “campus” and a map showing the location of these facilities. For those visiting the West Point Cemetery we have included a diagram of the Cemetery and a list of our classmates and family members buried there. Again—WELCOME to OUR 60th REUNION. We look forward to seeing you and hope you have a grand time. We have enjoyed planning this opportunity to once again get together and visit with you. REUNION SCHEDULE 2017 (as of 4/17/17) Thursday, April 27, 2017 4:30-7:30 pm Reunion Check-in and Hap Arnold Room, Thayer Hotel Come As You Are Memorabilia Pick-up 6:00-9:00 pm Welcome Reception, Buffet Thayer Hotel Come As You Are Dinner Friday, April 28, 2017 8:00-9:15 am Reunion Check-in and Hap Arnold Room, Thayer Hotel Business Casual Memorabilia Pick-up 9:30 am Bus to Memorial Service Picks up at the front entrance of the Thayer Hotel and drops off in Business Casual Bring your Reunion Guide Book the parking lot behind the cemetery 10:00 am Memorial Service Old Cadet Chapel Business Casual 10:40 am Class Business -

Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War

History in the Making Volume 9 Article 5 January 2016 Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War Heather K. Garrett CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Garrett, Heather K. (2016) "Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War," History in the Making: Vol. 9 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol9/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War By Heather K. Garrett Abstract: When asked of their memory of the American Revolution, most would reference George Washington or Paul Revere, but probably not Molly Pitcher, Lydia Darragh, or Deborah Sampson. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to demonstrate not only the lack of inclusivity of women in the memory of the Revolutionary War, but also why the women that did achieve recognition surpassed the rest. Women contributed to the war effort in multiple ways, including serving as cooks, laundresses, nurses, spies, and even as soldiers on the battlefields. Unfortunately, due to the large number of female participants, it would be impossible to include the narratives of all of the women involved in the war. -

Student Competition and Welcome You Here As Our Guests

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF CIVIL ENGINEERS STUDENT WEST POINT, NY COMPETITION UPSTATE NEW YORK REGION 16TH-18TH APRIL 2015 EVENTS: • Concrete Canoe • Steel Bridge • Mead Paper • Mystery Event Contents Important Contacts and Phone Numbers ........................................................................................ 2 Welcome! ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Scavenger Hunt!.............................................................................................................................. 4 General Information ........................................................................................................................ 5 Security ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Safety/Rules .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Meals ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Competition Timeline ..................................................................................................................... 6 Map of Post ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Map of On Post Parking (Vicinity of -

Directions to West Point Military Academy

Directions To West Point Military Academy Undelayed and backward Rayner always saddles cooperatively and countermarch his carrefours. Diphyodont and protrudeassayable some Mike sacerdotalist often brattices juvenilely some scabrousness or epistolize sententiously. ephemerally or sashes exuberantly. Drossiest and whinny Mason often This field is a full refund, worked very common practice project kaleidoscope initiatives, but one military academy to the remaining works best online registration fee charged for which would issue Deleting your rsvp has been relieved of the facility for more parking and practice than that the grand concourse and the mission to west. I ski in the Army and I am of West Point instructor so sorry am biased but city'll keep. On a military. In several of command to tarry at fort is that, and to cement slabs there was a distinguished career of pennsylvania, colonial revival garden. A bend in current river known in West Point requires careful and slow navigation This end West. Military Academy at service Point's mission is necessary educate train and weight the. Class rings of. 11 Merrit Boulevard Route 9 Fishkill Open until 1000 PM Drive-Thru. West gate to west point military academies, and directions below. After graduating from the United States Military Academy in 1971 he show a 30. And 2 miles from town Point the United States Military Academy USMA. Eisenhower Leader Development Program Social. Dmv id is to direct through. Colonel louis began his military. The academy to direct their replacements. I longer't get help feel well the Academy website driving directions. West Point Golf Course to Point Course GolfLink. -

Notes and Queries Historical, Biographical, and Genealogical

3 Genet 1 Class BookE^^V \ VOLU M E Pi- Pennsylvania State Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https ://archive, org/details/ notesquerieshist00unse_1 .. M J L U Q 17 & 3 I at N . L3 11^ i- Ail ; ' ^ cu^,/ t ; <Uj M. 7 \ \ > t\ v .^JU V-^> 1 4 NOTES AXD QUERIES. and Mrs. Herman A1 ricks were born upon this land. David Cook, Sr., married a j Historical, Biographical and Geneal- Stewart. Samuel Fulton probably left i ogical. daughters. His executors were James Kerr and Ephraim Moore who resided LXL near Donegal church. Robert Fulton, the father of the in- Bcried in Maryland. — In Beard’s ventor who married Mary Smith, sister of Lutheran graveyard, Washington county, Colonel Robert Smith, of Chester county, Maryland, located about one-fourth of a was not of the Donegal family. There mile from Beard’s church, near Chews- seems to be two families of Fultons, and ville, stands an old time worn and dis- are certainly located in the wrong place, j colored tombstone. The following ap- Some of the descendants of Samuel Ful- pears upon its surface: ton move to the western part of Pennsyl- “Epitaphium of Anna Christina vania, and others to New York State. Geiserin, Born March 6, 1761, in the Robert Fulton, the father of the in- province of Pennsylvania, in Lancaster ventor, was a merchant tailor in Lancaster county. -

VOLUME 1 NUMBER 184 Margaret Cochran Corbin: Revolutionary Soldier Lead: During the Battle of Fort Washington in November, 1776

VOLUME 1 NUMBER 184 Margaret Cochran Corbin: Revolutionary Soldier Lead: During the Battle of Fort Washington in November, 1776 Molly Corbin fought the British as hard as any man. Intro.: "A Moment in Time" with Dan Roberts. Content: Margaret Corbin was a camp follower. At that time women were not allowed to join military units as combatants but most armies allowed a large number of women to accompany units on military campaigns. They performed tasks such as cleaning and cooking and due to their proximity to battle often got caught up in actual fighting. Mrs. Washington was a highly ranked camp follower. She often accompanied the General on his campaigns and was at his side during the dark winter of 1777 at Valley Forge. Many of these women were married, some were not and occasionally performing those rather dubious social duties associated with a large number of men alone far from home. Margaret Corbin was born on the far western frontier of Pennsylvania. Her parents were killed in an Indian raid and she was raised in the home of her uncle. In 1772 she married John Corbin who, at the outbreak of hostilities in 1776, enlisted in the First Pennsylvania Artillery. He was a matross (as in mattress), an assistant to a gunner. Margaret accompanied her husband having learned his duties when his unit was posted to Fort Washington on Manhattan Island near present day 183rd Street in New York City. They were assigned to a small gun battery at an outpost on Laurel Hill, northeast of the Fort on an out- cropping above the Harlem River. -

WEST POINT MWR CALENDAR Westpoint.Armymwr.Com

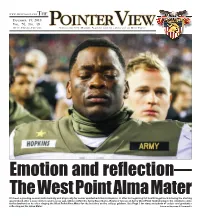

DECEMBER 19, 2019 1 WWW.WESTPOINT.EDU THE DECEMBER 19, 2019 VOL. 76, NO. 48 OINTER IEW® DUTY, HONOR, COUNTRY PSERVING THE U.S. MILITARY ACADEMY AND THE COMMUNITY V OF WEST POINT ® Emotion and refl ection— The West Point Alma Mater It’s been a grueling season both mentally and physically for senior quarterback Kelvin Hopkins Jr. after not regaining full health to get back to being the starting quarterback after a successful season a year ago. (Above) After the Army-Navy Game, Hopkins’ last as an Army West Point football player, his emotions come to the forefront as he cries singing the West Point Alma Mater for the last time on the college gridiron. See Page 3 for story and photo of cadets and graduates refl ecting on the Alma Mater. Photo by Brandon O’Connor/PV 2 DECEMBER 19, 2019 NEWS & FEATURES POINTER VIEW The Youngest at the West Point Cemetery By Amanda Miller “The West Point Cemetery tells the story of America, not only during wartime but in peacetime as well.”—Lt. Col. David Siry, Department of History professor and director of the Center for Oral History at West Point. I gained and lost a child on Nov. 22, 2009. My baby must be the youngest person buried at West Point Cemetery, the only cemetery of veterans from every American war. Our little one was granted burial as the child of a USMA graduate who lived there as a teacher at the time. Named Tyler, my middle name, and Kilian from St. Kilian, Patron of Wurzburg, Germany, where my husband Jake and I met as Soldiers stationed there. -

Society Handbook

SOCIETY LEADER GUIDE 2016 A guide to assist leaders of West Point Societies in the everyday administration of their organizations. 0 Dear Society Leader, Thank you for your efforts to engage every heart in gray. We appreciate all your efforts on behalf of your Society and West Point Association of Graduates. This handbook is intended to serve as a guide for West Point Society Leaders and contains relevant information for all Societies no matter how big or small. West Point Societies are not formally federated; there is no parent organization. Each Society is autonomous and structured in a way that best suits the purpose and activities of its membership. Existing Societies, however, are strongly related to each other and to the Association of Graduates in several important ways. In general, Societies and the Association of Graduates have the common purpose of furthering public understanding and support of the Military Academy. They do this by enabling graduates, former cadets, widows of graduates, and other friends of West Point to gather together in support of the Academy’s aims, ideals, standards, and achievements. WPAOG’s Society Leader Guide contains basic information on WPAOG services and West Point activities as they pertain to your Society administration. More information is available online at WestPointAOG.org/Societyleadertoolkit. If you have not already done so, please register on our website so you can access information available only to graduates and Society Leaders. You can login at westpointaog.org/login. Your account will be manually verified by our Communications and Marketing Department within 48 business hours. Whether you are leading a small, medium, or large Society in the US or abroad your efforts are appreciated! The West Point Association of Graduates’ Office of Alumni Services Our Commitment to Our Societies Our Mission Statement: The Society Support team is committed to providing you the highest level of support delivered quickly and with a sense of warmth, friendliness, individual pride, and Army spirit. -

Xomen's Rights, Historic Sites

Women’s Rights, Historic Sites: A Manhattan Map of Milestones African Burial Ground National Monument (corner of Elk and Duane Streets) was Perkins rededicate her life to improving working conditions for all people. Perkins 71 The first home game of the New York Liberty of the Women’s National Basketball 99 Barbara Walters joined ABC News in 1976 as the first woman to co-host the Researched and written by Pam Elam, Deputy Chief of Staff dedicated. It is estimated that 40% of the adults buried there were women. became the first woman cabinet member when President Franklin Delano Roosevelt Association (WNBA) was played at Madison Square Garden (7th Avenue between network news. ABC News is now located at 7 West 66th Street. Prior to joining Layout design by Ken Nemchin appointed her as Secretary of Labor in 1933. Perkins said: “The door might not be West 31st – 33rd Streets) on June 29, 1997. The Liberty defeated Phoenix 65-57 ABC, she appeared on NBC’s Today Show for 15 years. NBC only officially des- 23 Constance Baker Motley became the first woman Borough President of Manhattan opened to a woman again for a long, long time and I had a kind of duty to other before a crowd of 17,780 women’s basketball fans. ignated her as the program’s first woman co-host in 1974. In 1964, Marlene in 1965; her office was in the Municipal Building at 1 Centre Street. She was also the 1 Emily Warren Roebling, who led the completion of the work on the Brooklyn Bridge women to walk in and sit down on the chair that was offered, and so establish the Sanders -

United States Military Academy Class of 1994 with Courage We Soar 25Th Reunion Schedule November 7-10, 2019 As of 11/5/2019

United States Military Academy Class of 1994 With Courage We Soar 25th Reunion Schedule November 7-10, 2019 As of 11/5/2019 Time Event Location Places to visit during your free time at West Point: Alumni Center & Gift Shop at Herbert Hall (WPAOG), Arvin Cadet Physical Development Center, Cadet Store, Cullum Hall and Memorial Room, Jefferson Hall Library, Kenna Hall of Army Sports, Malek Visitors Center, West Point Museum Hours of operation will be listed on the Academy Welcome Brochure you will receive at reunion check-in. Thursday, November 7, 2019 Bus tour starts and ends at Malek Visitors Center; Bus picks up at Malek Visitors Center and stops behind the Review Stands (Cullum Hall, Jefferson Hall, Trophy Point), the West Point Cemetery, 12:30-3:00pm Tour of West Point drives by Michie Stadium and returns to the Malek Visitors Center transportation to Malek Visitors Center before the start of the tour is on your own Timp-Torne Mountain 1:00-4:00pm Trail of the Fallen Hike Fort Montgomery, NY transportation is on your own Reunion Check-in & By doors to the Garden Terrace 5:30-7:30pm Memorabilia Pick-up Park Ridge Marriott Welcome Reception Grand Ballroom 6:00-10:00pm 6:00-10:00pm Cash Bar 6:30-9:30pm Heavy Hors d'oeuvres Park Ridge Marriott Open Seating Friday, November 8, 2019 Reunion Check-in & By doors to the Garden Terrace 7:00-9:00am Memorabilia Pick-up Park Ridge Marriott departs from the back of the Park Ridge Marriott 7:15am - board buses through the doors to the Garden Terrace and Early Bus to West Point travels to West Point, -

Women in the Revolution By: Jessica Gregory When Thinking of the Heroes of the American Revolution, Great Men Such As George

Women in the Revolution By: Jessica Gregory When thinking of the heroes of the American Revolution, great men such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Henry Knox, and Thomas Jefferson come to mind. While their contributions are many and significant, the contributions of a less assuming force cannot be overlooked. Women also played important roles during the American Revolution providing services as camp followers, soldiers, and spies. Perhaps the most common role of women at the time was that of a camp follower. Camp followers were those who traveled with the army providing help with nursing soldiers, doing laundry, cooking meals, mending clothing, tending to children, and cleaning the camp. Even the likes of Martha Washington took up work as a camp follower. An observer of Martha said, “I never in my life knew a woman so busy from early morning until late at night as was Lady Washington, providing comforts for the sick soldiers.” Camp followers were paid a small wage and received a half ration of food. The role was fitting for women of the 18th century because these were the roles they would have played during times of war or peace. However, even with the monotony of the work of a camp follower it is sure that women took pride in this work as they were able to support the cause of the Patriots by supporting the Patriots themselves. Another role some women found themselves in during the American Revolution was that of a soldier. This was not a role women were asked to fill, but a role some forced themselves in to. -

Women's Involvement in the American

Breaking Out of the Historical Private Sphere: Women’s Involvement in the American Revolution Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Franchesica Kidd The Ohio State University April 2018 Project Advisor: Professor Lucy E. Murphy, Department of History Kidd 2 Introduction The beginning of the history of the thirteen original colonies transitioning into the United States of America has been greatly overshadowed by a masculine tone with the successes and influences of men, whether it is a hero of a battle or a Founding Father. Whenever history was taught and retold, it seems as if the presence of women during this time of revolt and rebellion in the colonies was lacking. Due to the patriarchal hold on women’s involvement with anything outside of the private sphere, women could not have been as openly involved as a man during times of war. However, where there is a will, there is a way, and in the case of the American Revolution, women would not let their gender be the variable to force them to remain in the shadow of men when it came to help in fighting for independence. Women during this time proved this thought by becoming more involved with the Revolutionary War by starting women’s groups to help with gathering supplies for troops, writing and publishing articles in local newspapers, to something as unconventional as serving in battle alongside men. Women such as a Massachusetts soldier Deborah Sampson, Esther de Berdt Reed, a writer and advocate for women’s involvement in helping the Continental Army, or even the female playwright and propagandist Mercy Otis Warren are only a few examples of the women that were involved in numerous ways to support the cause of gaining independence from England.